Last Updated: October 31, 2025

Introduction to the Extracellular Matrix

A substantial portion of the volume of tissues is extracellular space, which is largely filled by an intricate network of macromolecules constituting the extracellular matrix, ECM. The ECM is composed of two major classes of biomolecules: glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), most often covalently linked to protein forming the proteoglycans, and fibrous proteins which include collagen, elastin, fibronectin, and laminin. These components are secreted locally and assembled into the organized meshwork that is the ECM.

Connective tissue refers to the matrix composed of the ECM, cells (primarily fibroblasts), and ground substance that is tasked with holding other tissues and cells together forming the organs. Ground substance is a complex mixture of GAGs, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins (primarily laminin and fibronectin) but generally does not include the collagens. In most connective tissues, the matrix constituents are secreted principally by fibroblasts but in certain specialized types of connective tissues, such as cartilage and bone, these components are secreted by chondroblasts and osteoblasts, respectively. In addition to the extracellular matrix, typical connective tissues contain cells (primarily fibroblasts) all of which are surrounded by ground substance. The ECM is not only critical for connecting cells together to form the tissues, but is also a substrate upon which cell migration is guided during the process of embryonic development and importantly, during wound healing. In addition, the ECM is responsible for the relay of environmental signals to the surfaces of individual cells.

The extracellular matrix is composed of three major classes of biomolecules:

1. Structural proteins: e.g. the collagen, the fibrillins, and elastin.

2. Specialized proteins: e.g. fibronectin, the various laminins, and the various integrins.

3. Proteoglycans: these are composed of a protein core to which is attached long chains of repeating disaccharide units termed glycosaminoglycans (GAG) forming extremely complex high molecular weight components of the ECM. Although discussed below, greater details regarding the composition and function of the proteoglycans can be found in the page on Glycosaminoglycans and Proteoglycans.

Collagens

Collagens are the most abundant proteins found in the animal kingdom. The various collagens constitute the major proteins comprising the ECM. There are 46 different collagen genes dispersed through the human genome. These 46 genes generate proteins that combine in a variety of ways to create over 28 different types of collagen fibrils. The different collagen fibril types are identified by Roman numeral designation. Types I, II, and III collagens are the most abundant and all three types form fibrils of similar structure. Of these three major types of collagen, type I is by far the most abundant, constituting nearly 90% of all the collagen in the human body. Type IV collagen forms a two-dimensional reticulum and is a major component of all basement membranes. Collagens are predominantly synthesized by fibroblasts but epithelial cells are also responsible for the synthesis of some of the ECM collagen.

Collagens are synthesized as preproproteins (see next section) and undergo extensive co- and post-translational processing. Collagen protein monomers (termed α-chains) self-associate into a triple helical structure. Most of these triple helix structures (termed collagen fibrils) are composed of two identical alpha chains (e.g. α1) and a different alpha chain (e.g. α2). The nomenclature for collagens involves the chain composition and the numbering of the collagen gene encoding that particular α-chain. For example, type I collagen proteins are encoded by the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes with two of the triple helix proteins encoded by one gene and one by the other. Therefore type I collagen fibrils are denoted [α1(I)]2[α2(I)] where the Roman numeral designates the fibril as type I.

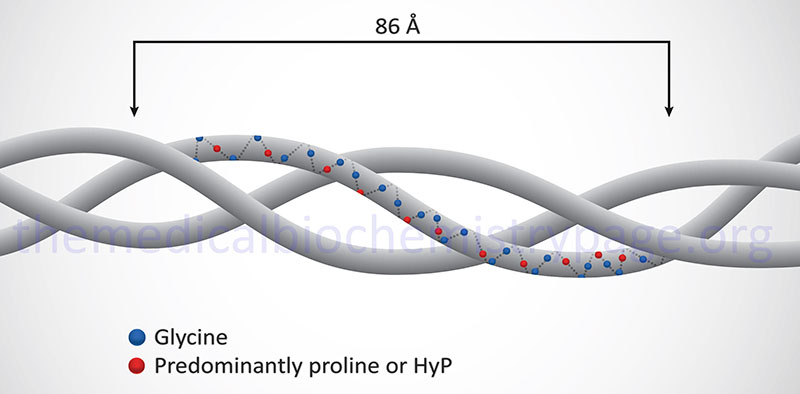

Collagen proteins have a unique amino acid composition unlike any other protein in the human body. These proteins contain upwards of hundreds of repeats of the sequence Gly-Pro-X or Gly-X-HyP, where X represents any amino acid except glycine or proline. HyP denotes hydroxyproline. As much as 35% of a collagen monomer is composed of glycine with another 20–25% being proline.

Collagen Synthesis and Processing

Collagens, like the majority of secreted proteins, are synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum (rough ER). Like all secreted and processed precursor proteins, collagens originate as longer precursor proteins called preprocollagens. Following removal of the signal peptide from the preprocollagen precursor, which occurs in the lumen of the rough ER, the remaining protein is referred to as a procollagen (or tropocollagen). Procollagen proteins contain extra amino acids at the N- and C-termini that will be removed during the further processing that occurs. For example, type I procollagen contains an additional 150 amino acids at the N-terminus and 250 at the C-terminus. These pro-domains are globular and form multiple intrachain disulfide bonds. The disulfide bonds stabilize the proprotein allowing the triple helical section to form. Collagen fibers begin to assemble in the ER and the Golgi complex.

In addition to signal sequence removal, numerous additional modifications take place to amino acids residues on the procollagen proteins. These modifications include hydroxylations and carbohydrate additions. Specific proline residues are hydroxylated by prolyl 3-hydroxylase and prolyl 4-hydroxylase. Specific lysine residues also are hydroxylated by lysyl hydroxylases. Both prolyl and lysyl hydroxylases are absolutely dependent upon ascorbic acid (vitamin C) as co-factor. The proly 3- and prolyl 4-hydroxylases all belong to the large family of 2-oxoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases (2OG-oxygenases) whose members are most notable for their roles in histone demethylation and the regulation of cellular responses to hypoxia initiated by HIF-1.

Humans express three distinct prolyl 3-hydroxylase genes (P3H1, P3H2, and P3H3). Humans contain a fourth gene, P3H4, in this gene family but the encoded protein is not active as a proly 3-hydroxylase.

- The P3H1 gene is located on chromosome 1p34.2 and is composed of 16 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a unique precursor protein.

- The P3H2 gene is located on chromosome 3q28 and is composed of 17 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode unique precursor proteins.

- The P3H3 gene is located on chromosome 12p13.31 and is composed of 15 exons that encode a 736 amino acid precursor protein.

Human prolyl 4-hydroxylases are functional as heterotetrameric enzymes composed of two α-subunits (the catalytic subunits) and two β-subunits. Humans express four distinct prolyl 4-hydroxylase α-subunit genes (P4HA1, P4HA2, P4HA3, and P4HTM) and one β-subunit gene (P4HB).

- The P4HA1 gene is located on chromosome 10q22.1 and is composed of 17 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding three distinct precursor proteins.

- The P4HA2 gene is located on chromosome 5q31.1 and is composed of 18 exons that generate nine alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode three different precursor proteins with the 533 amino acid isoform 2 precursor being the prevalent product.

- The P4HA3 gene is located on chromosome 11q13.4 and is composed of 15 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode unique precursor proteins.

- The P4HTM gene is located on chromosome 3p21.31 and is composed of 9 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode unique precursor proteins. The protein encoded by the P4HTM gene is a transmembrane protein localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. The P4HTM protein functions in the modulation of cellular responses to hypoxia by altering the activity of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1). The P4HTM encoded protein hydroxylates proline residues in the HIF-1α subunit of the HIF-1 complex which targets the protein for ubiquitylation and degradation via the proteasome pathway.

- The P4HB gene is located on chromosome 17q25.3 and is composed of 10 exons that encode a 508 amino acid precursor protein. The P4HB encoded protein is a member of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family of proteins that catalyze exchange reactions between thiols and disulfides.

Humans express three distinct lysyl hydroxylase genes identified as PLOD1, PLOD2, and PLOD3. PLOD stands for procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase. Each of the lysyl hydroxylase enzymes, like the prolyl hydroxylases, are members of the large family of 2-oxoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases (2OG-oxygenases).

- The PLOD1 gene is located on chromosome 1p36.22 and is composed of 20 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNA encoding precursor proteins of 774 amino acids (isoform 1) and 727 amino acids (isoform 2).

- The PLOD2 gene is located on chromosome 3q24 and is composed of 23 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding precursor proteins of 758 amino acids (isoform 1) and 737 amino acids (isoform 2).

- The PLOD3 gene is located on chromosome 7q22.1 and is composed of 19 exons that encode a 738 amino acid precursor protein.

Glycosylations of the O-linked type also take place during procollagen transit through the Golgi complex. Many, but not all, hydroxylated lysine residues (HyL), but not the HyP residue, are targets for O-glycosylation. The most common sugars added during this step are glucose or galactose as monomeric sugar attachments. Later, within the Golgi complex, oligosaccharides are added to the procollagen proteins. The hydroxylation and glycosylation reactions allow the procollagen proteins to twist upon themselves forming the typical triple helical structure.

Following completion of collagen protein processing, within the ER and Golgi complex, the globular ends of the triple helices are loose. The procollagen proteins are then secreted into the extracellular space. Several reactions take place to a procollagen protein within the extracellular compartment. Proteases remove the globular pro-domains at both the N- and C-termini. The collagen molecules then polymerize to form collagen fibrils. Accompanying fibril formation is the oxidation of certain lysine residues by the extracellular enzyme lysyl oxidase. Lysyl oxidase is an extracellular Cu2+-dependent enzyme that is also known as protein-lysine 6-oxidase. The lysyl oxidase gene (symbol: LOX) is located on chromosome 5q23.1 and is composed of 8 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a distinct precursor isoform. Lysyl oxidase acts on lysines and hydroxylysines producing aldehyde groups, which will eventually undergo covalent bonding between tropocollagen molecules. As indicated, lysyl oxidase is a major Cu2+-dependent enzyme. As such, defects in copper homeostasis, as is evident in Menkes disease, result in numerous manifestations related to defective collagen production.

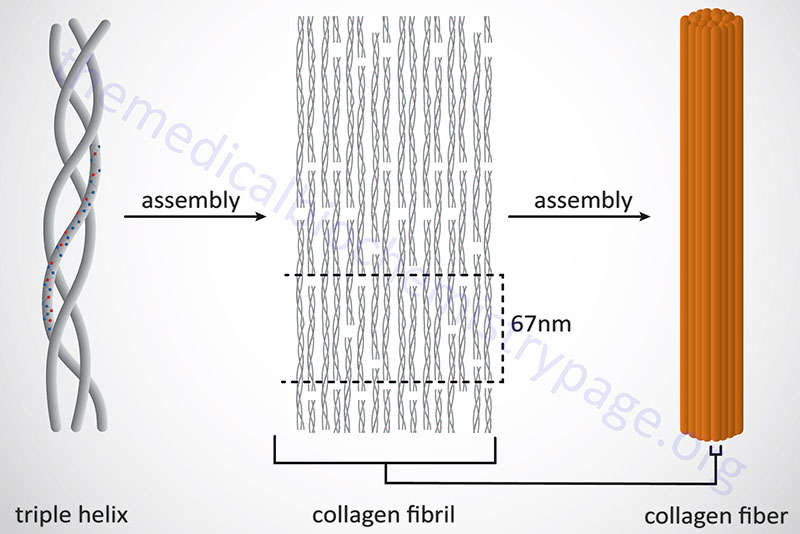

The fundamental higher order structure of all collagens is a long and thin diameter rod-like protein. The Table below lists the characteristics of the 12 most highly characterized types of collagen fibrils. As indicated above, there are at least 28 different types of collagen fibrils in the various types of extracellular matrices of the human body. For example, type I collagen is 300nm long, 1.5nm in diameter and consists of 3 coiled subunits composed of two α1(I) chains and one α2(I) chain. Characteristic of type I collagen, but highly similar in all other types, there are three amino acids per turn of the helix and every third amino acid is a Gly.

In addition to the high Gly content, collagens are also rich in Pro and HyP residues. The R-groups of the latter two amino acids reside on the outside of the triple helix. Lateral interactions of triple helices of collagens result in the formation of fibrils roughly 50nm diameter. The packing of collagen is such that adjacent molecules are displaced approximately 1/4 of their length (67nm). This staggered array produces a striated effect that can be seen in the electron microscope.

Types of Collagen

| Type | Chain Composition | Gene Symbol(s) | Structural Details | Comments |

| I: fibril forming | [α1(I)]2[α2(I)] | COL1A1, COL1A2 | 300nm, 67nm banded fibrils | skin, tendon, bone, etc.; most abundant collagen protein in the human body representing up to 90% of all collagen proteins |

| II: fibril forming | [α1(II)]3 | COL2A1 | 300nm, small 67nm fibrils | cartilage, vitreous humor |

| III: fibril forming | [α1(III)]3 | COL3A1 | 300nm, small 67nm fibrils | skin, muscle, frequently with type I |

| IV: sheet forming | [α1(IV)2[α2(IV)] | COL4A1 thru COL4A6 | 390nm C-term globular domain, nonfibrillar | all basal lamina; is the major structural component of all basement membranes; COL4A3 encodes what is called the Goodpasture antigen as this protein is antigenically recognized in the autoimmune disorder called Goodpasture syndrome |

| V: fibril forming | [α1(V)][α2(V)][α3(V)] | COL5A1, COL5A2, COL5A3 | 390nm N-term globular domain, small fibers | most interstitial tissue, assoc. with type I |

| VI: fibril forming | [α1(VI)][α2(VI)][α3(VI)] | COL6A1, COL6A2, COL6A3 | 150nm, N+C term. globular domains, microfibrils, 100nm banded fibrils | most interstitial tissue, assoc. with type I |

| VII: anchoring | [α1(VII)]3 | COL7A1 | 450nm, dimer | epithelia |

| VIII | [α1(VIII)]3 | COL8A1, COL8A2 | some endothelial cells | |

| IX: anchoring | [α1(IX)][α2(IX)][α3(IX)] | COL9A1, COL9A2, COL9A3 | 200nm, N-term. globular domain, bound proteoglycan | FACIT collagen (Fibril Associated Collagens with Interrupted Triple helices) cartilage, associates with type II |

| X | [α1(X)]3 | COL10A1 | 150nm, C-term. globular domain | hypertrophic and mineralizing cartilage |

| XI | [α1(XI)][α2(XI)][α3(XI)] | COL11A1, COL11A2 | 300nm, small fibers | cartilage |

| XII: anchoring | α1(XII) | COL12A1 | FACIT collagen; tendons, skin, placenta; interacts with types I and III |

Clinical Significance of Collagen Disorders

Collagens are the most abundant proteins in the body. Alterations in collagen structure, resulting from abnormal collagen genes or abnormal processing of collagen proteins, results in numerous diseases, e.g. Alport syndrome, Larsen syndrome, and numerous chondrodysplasias as well as the more commonly known clusters of related syndromes of osteogenesis imperfecta and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is actually the name associated with at least nine phenotypically characterized that result from different types of mutations in at least five different collagen genes and two collagen processing genes. Each of these nine disorders are biochemically and clinically distinct yet all manifest with structural weakness in connective tissue as a result of defects in the overall structure and function of collagens.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) also encompasses more than one disorder. At least four biochemically and clinically distinguishable disorders have been identified in the spectrum of OI disorders that are caused by defects in collagen genes. These four OI forms are identified as type I (mild), type II (perinatal lethal), type III (deforming), and type IV (mild deforming). All four forms are characterized by multiple fractures and resultant bone deformities. In addition to the four forms of OI caused by collagen defects, there are at least eleven additional phenotypically related disorders in the OI family. Like the four classical collagen defect forms of OI, each of the other eleven forms of OI are associated with bone fragility and low bone mass.

Marfan syndrome (MFS) manifests itself as a disorder of the connective tissue and was believed to be the result of abnormal collagens. However, recent evidence has shown that MFS results from mutations in the extracellular protein, fibrillin 1, encoded by the FBN1 gene. (see next section). Fibrillin 1 is one of three fibrillins expressed in human tissues, each of which is an integral constituent of the non-collagenous microfibrils of the extracellular matrix.

Defective copper absorption from the gut results from mutations in the copper transporter identified as ATP7A. Mutations in this gene result in the devastating disorder known as Menkes disease. Many of the manifesting symptoms associated with Menkes disease are due to loss of proper collagen processing due to defective lysyl oxidase activity.

Type IV collagens are major structural proteins in all basement membranes. There are six type IV collagen genes in humans identified as COL4A1–COL4A6. The protein encoded by the COL4A3 gene is expressed at high levels in the basement membranes of pulmonary alveoli and in renal glomeruli. The symptoms of the autoimmune disease known as Goodpasture syndrome are caused by autoantibodies made against the COL4A3 encoded protein. Goodpasture syndrome (also referred to as anti-glomerular basement antibody disease: anti-GBM disease) manifests with symptoms that are principally the result of renal and pulmonary involvement. Common symptoms of Goodpasture syndrome include shortness of breath, chest pain, coughing up blood, blood in the urine, protein in the urine, hypertension, and swelling of the face and limbs. Because this disease is an autoimmune syndrome, afflicted individuals need to be treated with immunosuppressant drugs. Plasmapheresis, a process whereby the cells in the blood are separated from the plasma (which contains the autoantibodies), is often utilized in acute treatment of afflicted individuals.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a term referring to a family of disorders that are associated with excessive blistering in response to mechanical injury or trauma. Children with these disorders are often referred to as “butterfly wing” children because of their extremely fragile skin (like the fragility of a butterfly’s wing) which can shed at the slightest touch in some patients. There are three distinct classifications of EB: simplex, junctional, and dystrophica. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is caused by defects in the COL7A1 gene. The autosomal dominant form of DEB is also known as Cockayne-Touraine disease, whereas, the autosomal recessive form is also known as Hallopeau-Siemens disease.

Fibrillins and Elastin

The ECM of tissues that undergo significant stretching and/or bending contains significant quantities of the protein elastin. Elastin is found in a specialized type of fibril called elastic fibers. Elastic fibers are composed of large masses of cross-linked elastin interspersed with another family of ECM proteins called the fibrillins. The walls of large arteries are particularly abundant with elastin (and thus elastic fibers) which allows them to undergo continual deformation and reformation during changes in intravascular pressure. The lungs and the skin are additional organs whose tissues are rich in elastin and elastic fibers.

Elastin

Elastin is synthesized as the precursor, tropoelastin from the elastin gene (symbol: ELN). The ELN gene is located on chromosome 7q11.23 and is composed of 34 exons that generate 13 alternatively spliced mRNAs. Tropoelastin has two major types of alternating domains. One domain is hydrophilic and rich in Lys (K) and Ala (A) while the other domain is hydrophobic and rich in Val (V), Pro (P), and Gly (G) where these amino acids are frequently contained in repeats of either VPGVG or VGGVG. The hydrophobic domains of elastin are responsible for its elastic character.

Tropoelastin is translated and then secreted as a mature protein into the extracellular matrix and accumulates at the surface of the cell. After secretion and alignment with ECM fibrils, numerous K residues are oxidized by lysyl oxidase (gene symbol: LOX), a reaction which initiates cross-linking of elastin monomers. This process of elastin cross-linking, induced by lysyl oxidase, is the same as occurs in the cross-linking of collagens. Although lysyl oxidase activity promotes elastin cross-linking, the process is unique in that three lysine-derived aldehydes (allysyl) cross-link with an unmodified lysine forming a tetrafunctional structure called a desmosine. The highly stable cross-linking of elastin is what ultimately imparts the elastic properties to elastic fibers.

Loss of the elastin gene is found associated with the disorder known as Williams-Beuren syndrome (also known as just Williams syndrome) which is, in part, characterized by connective tissue dysfunction that plays a causative role in the supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS) typical of this disorder. Williams-Beuren syndrome results from spontaneous deletion of a region of the q arm (q11.23) of one of the two copies of chromosome 7. This deleted region of chromosome 7 contains 26–28 different genes, including the ELN gene, leading to hemizygosity for these genes. Defective elastin is also associated with a group of skin disorders called cutis laxa (autosomal dominant form in the case of ELN gene defects). In these disorders the skin has little to no elastic character and hangs in large folds.

Fibrillins

The other major proteins in elastic fibers are the fibrillins. Humans express three fibrillin genes identified as FBN1, FBN2, and FBN3. The FBN1 gene is located on chromosome 15q21.1 and is composed of 66 exons that encode a 2871 amino acid precursor protein. The FBN2 gene is located on chromosome 5q23.3 and is composed of 65 exons that encode a 2912 amino acid precursor protein. The FBN3 gene is located on chromosome 19p13.2 and is composed of 68 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode the same 2809 amino acid precursor protein.

Fibrillin monomers link head to tail in microfibrils which can then form two and three dimensional structures. The most abundant fibrillin in elastic fibers is the FBN1 encoded protein, fibrillin 1. Fibrillin 1 serves as the scaffold in elastic fibers upon which cross-linked elastin is deposited. The observed patterns of fibrillin gene expression are consistent with their roles in extracellular matrix structure of connective tissue. FBN1 expression is high in most cell types of mesenchymal origin, particularly bone. FBN2 expression is highest in fetal cells and has more restricted expression in mesenchymal cell types postnatally. FBN3 is expressed in embryonic and fetal tissues in humans. The patterns of fibrillin gene expression indicates that these proteins are important in maintaining the structure and integrity of the extracellular matrix.

Mutations in fibrillin genes result in connective tissue disorders referred to as fibrillinopathies. These disorders are characterized by structural failure of the extracellular matrix due to the absence or abnormality in fibrillin proteins. The various fibrillinopathies that have been characterized to date result from mutations in either the FBN1 or FBN2 genes. No diseases are currently known to be associated with the FBN3 gene in humans. The FBN1-associated fibrillinopathies include Marfan syndrome (MFS), familial ectopia lentis, familial aortic aneurysm ascending and dissection, autosomal dominant Weill-Marchesani syndrome type 2 (WMS2), and MASS syndrome (MASS designates the involvement of the mitral valve, aorta, skeleton, and skin). The FBN2-associated fibrillinopathy is congenital contractural arachnodactyly.

Fibulins

Fibulins (pronounced FIE byoo lins) are calcium-binding glycoproteins that serve major components of elastic fibers in the ECM. The fibulins function to allow tissues the ability to contract after stretching, a property referred to as elastogenesis. Humans express eight fibulin family member genes identified as FBLN1, FBLN2, FBLN5, FBLN7, EFEMP1 (EGF containing fibulin extracellular matrix protein 1; formerly FBLN3), EFEMP2 (formerly FBLN4), HMCN1 (hemicentin 1; formerly FBLN6), and HMCN2.

The fibulin proteins all contain a domain at the C-terminus termed the fibulin-type globular domain and a variable number of EGF-like domains. Some of the fibulin EGF-like domains also contain a calcium-binding consensus sequence (cbEGF-like). The N-terminus of the fibulins is highly variable when comparing the different fibulins to each other.

The various fibulins are subdivided into subgroups defined their overall structure. Fibulin-1 and fibulin-2 which both contain three anaphylatoxin-like domains constitute subgroup I while the remaining fibulin family member proteins constitute subgroup II. The EFEMP1, EFEMP2, and FBLN5 encoded proteins are the smallest proteins in the family and as such are referred to as short fibulins. The protein encoded by the HMCN1 gene is the largest member of the fibulin protein family and contains a number of motifs not found in the other fibulins. The HMCN1 encoded protein contains a von Willebrand factor type C motif (VWFC domain), six thrombospondin type 1 repeats (TSP1 repeats), and 44 immunoglobulin C2-set domains.

Studies on the expression and functions of fibulin-1 have been the most extensive and initial characterizations demonstrated an association of the protein with elastic fibers. The FBLN1 gene is widely expressed and fibulin-1 is found associated with the ECM of various organs. Expression of the FBLN2, EFEMP1, and EFEMP2 genes are more restricted but the encoded proteins are found in some tissues with fibulin-1. The EFEMP1 (fibulin-3) and EFEMP2 (fibulin-4) encoded proteins are predominantly found in the walls of capillaries and larger vessels as well as in perineural tissues. Both fibulin-1 and fibulin-2 are expressed in early embryos with high levels observed during organogenesis. Both fibulin-1 and fibulin-2 are subsequently found where epithelial to mesenchymal transitions are occurring. Fibulin-2 is important in early cartilage development and during bone mineralization. Expression of both the FBLN1 and FBLN2 genes decreases in the adult. The role of fibulin-1 and fibulin-2 in arterial structure and function can be demonstrated from the fact that expression of both genes is activated in response to arterial injury.

The fibulins interact with numerous other ECM proteins, an effect that in many circumstances requires calcium-binding. Both fibulin-1 and fibulin-2 interact with fibronectins, laminins, various proteoglycans of the ECM, members of the cellular communication network factor family of growth factors (originally referred to as connective tissue growth factors, CTGF), and β-amyloid precursor protein (APP). The interaction of fibulin-1 with APP occurs is a calcium-dependent process and the result of this interaction is an inhibition of APP-mediated neurite outgrowth and neuronal stem cell proliferation.

Fibronectin

Fibronectin is a major fibrillar glycoprotein of the ECM where its role is to attach cells to a variety of ECM types. Fibronectin attaches cells to all extracellular matrices except type IV. Type IV matrices involve laminins as the adhesive proteins. Fibronectin is functional as a dimer of two similar peptide chains. Each chain is 60–70nm long and 2–3nm thick. At least 11 different fibronectin proteins have been identified that arise by alternative RNA splicing of the primary transcript from a single fibronectin gene (symbol: FN1). The FN1 gene is located on chromosome 2q35 and is composed of 46 exons that generate at least 18 different alternatively spliced mRNAs. Not all the resulting mRNAs encode functional fibronectin proteins, but at least 11 fibronectin preproproteins have been characterized.

Fibronectin consists of a multimodular structure composed predominantly of three different amino acid repeat domains termed modules. These repeat domains are termed FN-I, FN-II, and FN-III. The three fibronectin repeat domains are each composed of two anti-parallel β-sheets. In the FN-I and FN-II domains these β-sheets are held together by intrachain disulfide bonding. Each of the two fibronectin subunits in a functional fibronectin dimer consists of twelve FN-I, two FN-II, and fifteen to seventeen FN-III modules, respectively. These functional modules are responsible for fibronectin binding to fibrin, collagen, heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG), DNA, and the integrins in plasma membranes. The primary amino acid sequence motif in fibronectin that binds to an integrin is a tripeptide, Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD).

The FN-I domain is approximately 40 amino acids in length and contains four conserved cysteine residues that are required for disulfide bond formation. Several other proteins, in addition to fibronectin, contain one or more of the three FN-domains. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and factor XII, both proteins involved in the regulation of hemostasis, contain FN-I domains. In tPA the FN-I domain plays a role in binding to fibrin in a fibrin clot.

The FN-II domain is composed of approximately 60 amino acids that, like the FN-I domain, contains four conserved cysteine residues necessary for disulfide bond formation. Several proteins contain FN-II domains including factor XII, the IGF-2 receptor, and the receptor for a secretory phospholipase PLA2 (sPLA2) family member.

The FN-III domain is composed of approximately 100 amino acids that forms a β-sandwich structure. The FN-III domain is widely distributed, being found in over 100 human proteins, many of which are involved in the formation of the extracellular matrix.

Fibronectin is also found in a soluble compact non-functional form in the blood. This form of fibronectin is also known as cold-insoluble globulin (CIg). The transformation from the compact form to the extended fibrillar form of fibronectin is referred to as fibrillogenesis. This transformation requires the application of mechanical forces generated by cells. This occurs as cells bind and exert forces on fibronectin through transmembrane receptor proteins of the integrin family (see below).

Laminins

All basal lamina contain a common set of proteins, glycosaminoglycans (GAG), and proteoglycans (also see below). These include type IV collagen, heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), nidogens (entactins), and laminins. Because of the presence of type IV collagens, the basal lamina is often referred to as the type IV extracellular matrix. Each of the components of the basal lamina is synthesized by the cells that rest upon it. Laminins anchor cell surfaces to the basal lamina.

Laminins are heterotrimeric proteins that contain an α-chain, a β-chain, and a γ-chain. The historical designations for these three protein chains was A, B1 and B2, respectively. Humans express five genes encoding the α-chains, four encoding the β-chains, and three encoding the γ-chains. The five laminin α-chain encoding genes are identified as LAMA1, LAMA2, LAMA3, LAMA4, and LAMA5. The four laminin β-chain encoding genes are identified as LAMB1, LAMB2, LAMB3, and LAMB4. The three laminin γ-chain encoding genes are identified as LAMC1, LAMC2, and LAMC3.

The different laminin proteins have been found to form at least 15 different types of heterotrimers. The nomenclature for a laminin molecule relates to the peptide chain composition. For example, the laminin molecule identified as laminin-111 (originally identified as laminin-1) is composed of the α1, β1, and γ1 gene encoded proteins (α1β1γ1 composition), and laminin-211 (formerly laminin-2) has the composition, α2β1γ1. Laminin heterotrimers are quite large, ranging from under 500,000 to nearly a 1,000,000 Da in mass. Laminins contain common structural features that include a tandem distribution of globular, rod-like and coiled-coil domains. The coiled-coil domains are responsible for joining the three chains into a characteristic heterotrimeric structure.

Table of Human Laminin Forms

| Laminin | Subunit Composition | Previous Designation |

| Laminin-111 | α1β1γ1 | Laminin-1 |

| Laminin-211 | α2β1γ1 | Laminin-2 |

| Laminin-121 | α1β2γ1 | Laminin-3 |

| Laminin-211 | α2β2γ1 | Laminin-4 |

| Laminin-332 | α3β3γ2 | Laminin-5 |

| Laminn-311 | α3β1γ1 | Laminin-6 |

| Laminin-321 | α3β2γ1 | Laminin-7 |

| Laminin-411 | α4β1γ1 | Laminin-8 |

| Laminin-421 | α4β2γ1 | Laminin-9 |

| Laminin-511 | α5β1γ1 | Laminin-10 |

| Laminin-521 | α5β2γ1 | Laminin-11 |

| Laminin-213 | α2β1γ3 | Laminin-12 |

| Laminin-423 | α4β2γ3 | Laminin-14 |

| Laminin-522 | α5β2γ2 | |

| Laminin-523 | α5β2γ3 | Laminin-15 |

The laminins are glycoproteins that constitute the structural scaffolding of all basement membranes. The heterotrimer composition of laminins results from self-assembly following secretion of the individual protein subunits. Laminins are critical components of the ECM that bind to the integrins, the dystroglycans, and numerous other receptors. These laminin interactions are critical for cell differentiation, cell movement, cell shape, and the promotion of cell survival.

Given this broad range of contributions to tissue formation and survival, it is not surprising that loss of functional laminin genes can result in potentially devastating disorders. As described above in the collagen section, the disorders known as epidermolysis bullosa (EB) are a family of disorders that are associated with excessive blistering in response to mechanical injury or trauma. The junctional form of EB can be caused by mutations in either an integrin gene (ITGA6 and ITGB4) or a laminin gene (LAMA3, LAMB3, and LAMC2). A form of congenital muscular dystrophy is caused by defective laminin-211 production due to defects in the LAMA2 gene.

Table of the Laminin Genes Expressed in Humans

| Laminin Gene | Gene Location/ Structure | Comments |

| LAMA1 | 18p11.3; 64 exons | laminin, alpha 1; precursor protein of 3075 amino acids; mutations in gene associated with Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome which is an autosomal recessive disorder resulting in retinal dystrophy, eye movement disorders, delayed speech and motor development associated with cerebellar dysplasia |

| LAMA2 | 6q22–q23; 66 exons | laminin, alpha 2; alternative splicing yields two mRNAs that produce two isoforms; mutations in gene result in autosomal recessive merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy type 1A (MDC1A); muscle weakness apparent at birth, hypotonia, poor feeding; brain imaging of patients will show abnormalities in periventricular grey matter |

| LAMA3 | 18q11.2; 77 exons | laminin, alpha 3; five alternatively spliced mRNAs give rise to three different isoforms; mutations in gene associated with Herlitz-type junctional epidermolysis bullosa |

| LAMA4 | 6q21; 39 exons | laminin, alpha 4; three alternatively spliced mRNAs give rise to three isoforms |

| LAMA5 | 20q13.2–q13.3; 81 exons | laminin, alpha 5; gene encodes a 3695 amino acid precursor protein; this alpha chain is found in laminin-511, laminin-521, and laminin-523 |

| LAMB1 | 7q22; 35 exons | laminin, beta 1; gene encodes a 1786 amino acid precursor protein; found in the majority of basement membrane laminins |

| LAMB2 | 3p21; 32 exons | laminin, beta 2; gene encodes a 1798 amino acid precursor protein; restricted expression to vascular smooth muscle, renal glomerulus, and neuromuscular junction |

| LAMB3 | 1q32; 25 exons | laminin, beta 3; three alternatively spliced mRNAs all of which generate the same 1172 amino acid precursor protein; found in laminin-332; mutations in gene associated with Herlitz-type junctional epidermolysis bullosa and atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa |

| LAMB4 | 7q31; 42 exons | laminin, beta 4; gene encodes a 1761 amino acid precursor protein |

| LAMC1 | 1q31; 28 exons | laminin, gamma 1; was originally identified as laminin B2; gene encodes a 1609 amino acid precursor protein |

| LAMC2 | 1q24–q31: 23 exons | laminin, gamma 2; was originally identified as a truncated form of laminin B2 (B2t); expression restricted to epithelial cells of lung, skin, and kidney; two differentially expressed mRNAs generated from the gene encode different isoforms; mutations in gene associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa |

| LAMC3 | 9q34.12; 29 exons | laminin, gamma 3; gene encodes a 1575 amino acid precursor protein |

Integrins

The term integrin was derived from the observations that these cell-surface proteins (the integrins) served as transmembrane linkers (integrators) whose functions were to mediate the interactions between the extracellular matrix and the intracellular cytoskeleton. Integrins function as heterodimeric glycoproteins, composed of an α- and a β-subunit. Humans express 18 integrin α-subunit genes and 8 integrin β-subunit genes. Together these α- and β-subunits combine to form at least 24 identified heterodimeric complexes. Both subunits of an integrin are single pass transmembrane proteins, which bind components of the extracellular matrix or counter-receptors expressed on other cells. Several different matrix proteins are bound by integrins, such as laminins and fibronectin. Many ligands for the integrins bind only in the presence of the divalent cations, Ca2+ or Mg2+.

One class of integrin contains an inserted domain (I) in its α-subunit, and if present (in α1, α2, α10, α11, αD, αE, αL, αM and αX), this I domain contains the ligand binding site. All β-subunits possess a similar I-like domain, which has the capacity to bind ligand, often recognizing the RGD motif such as that present in fibronectin. The I and I-like domains of the integrins are what bind the divalent cations that are essential, in many types of integrin, for ligand binding.

Integrins provide a link between ligand and the actin cytoskeleton via short intracellular domains. This linkage between the outside (extracellular matrix) and inside (cytoskeleton) of cells, mediated by integrin-ligand interactions, allows for both outside-in and inside-out signal transduction. Integrin-ligand interactions can trigger certain intracellular signal transduction pathways via the regulation of the activity of certain protein kinases. These kinases include focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and integrin-linked kinase (ILK).

Table of the Integrin Genes Expressed in Humans

| Integrin Gene | Common Name | Comments |

| ITGAD | integrin, alpha D | formerly CD11d |

| ITGAE | integrin, alpha E | also known as CD103 antigen and human mucosal lymphocyte antigen 1, alpha polypeptide; forms a complex with the integrin β7 subunit |

| ITGAL | integrin, alpha L | also known as lymphocyte function antigen 1 (LFA-1), alpha polypeptide and CD11A antigen |

| ITGAM | integrin, alpha M | also known as complement component 3 receptor 3 polypeptide; formerly CD11b |

| ITGAV | integrin, alpha V | formerly CD51 |

| ITGAX | integrin, alpha X | also known as complement component 3 receptor 4 subunit; formerly CD11c |

| ITGA1 | integrin, alpha 1 | |

| ITGA2 | integrin, alpha 2 | is the alpha subunit of a platelet collagen receptor; also known as alpha 2 subunit of VLA-2 (very late antigen 2) receptor; also called platelet glycoprotein GPIa (GP1A) of the GPIa/IIa complex; formerly CD49B |

| ITGA2B | integrin, alpha 2b | is commonly known as GPIIb (GP2B) of the platelet glycoprotein complex GPIIb/IIIa |

| ITGA3 | integrin, alpha 3 | also known as alpha 3 subunit of VLA-3 (very late antigen 3) receptor; formerly CD49C; forms a complex with the integrin β1 subunit |

| ITGA4 | integrin, alpha 4 | also known as alpha 4 subunit of VLA-4 (very late antigen 4) receptor; formerly CD49D |

| ITGA5 | integrin, alpha 5 | formerly CD49E; is a component of the receptor for fibronectin |

| ITGA6 | integrin, alpha 6 | formerly CD49F; interacts with TSPAN-4 which is a member of the transmembrane 4 superfamily referred to as the tetraspanin family |

| ITGA7 | integrin, alpha 7 | functions as a receptor for laminin-1; gene defects associated with congenital myopathy |

| ITGA8 | integrin, alpha 8 | forms a complex with the integrin β1 subunit; involved in organogenesis and wound healing; gene defects associated with renal hypodysplasia/aplasia-1 (RHDA1) |

| ITGA9 | integrin, alpha 9 | forms a complex with the integrin β1 subunit; this complex is a receptor for vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), osteopontin (a bone-specific sialoprotein), and tenascin-C (an extracellular matrix glycoprotein involved in glial cell-neuron interactions) |

| ITGA10 | integrin, alpha 10 | highest levels of expression seen in chondrocytes; binds to collagen |

| ITGA11 | integrin, alpha 11 | forms a complex with the integrin β1 subunit; highest expression in muscle |

| ITGB1 | integrin, beta 1 | commonly called platelet glycoprotein GPIIa (GP2A); also known as the fibronectin receptor, beta polypeptide; formerly CD29 |

| ITGB2 | integrin, beta 2 | also known as complement component 3 receptor 3 and 4 subunit; gene defects result in leukocyte adhesion deficiencies |

| ITGB3 | integrin, beta 3 | commonly called platelet glycoprotein GPIIIa (GP3A) found in the GPIIb/IIIa complex; formerly CD61 |

| ITGB4 | integrin, beta 4 | associates with integrin α6 subunit; forms a receptor for laminins; gene defect associated with epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia |

| ITGB5 | integrin, beta 5 | |

| ITGB6 | integrin, beta 6 | forms a complex with integrin αV subunit; complex can bind fibronectin |

| ITGB7 | integrin, beta 7 | forms a complex with the integrin α4 and also the integrin αE subunits; the α4β7 complex is a leukocyte homing receptor in intestinal mucosa and Peyer’s patches; the αEβ7 complex binds binds to E-cadherin |

| ITGB8 | integrin, beta 8 |

Thrombospondins

Thrombospondin is the term that was used to define a “thrombin-sensitive protein” first isolated from platelets that had been stimulated with thrombin. Subsequent to the initial characterization of this protein, which is now called thrombospondin 1 (TSP1), several similar proteins have been identified and the human thrombospondin family now consists of five proteins identified as TSP1, TSP2, TSP3, TSP4, and COMP (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein; also referred to as TSP5). The genes that encode these five thrombospondin family proteins are designated THBS1, THBS2, THBS3, THBS4, and COMP.

Most of the information regarding expression and function of the thrombospondins comes from work carried out with TSP1 and TSP2. The five thrombospondin proteins are divided into two subgroups determined by their domain structure. Subgroup A includes TSP1 and TSP2 while subgroup B includes TSP3, TSP4, and COMP (TSP5). The subgroup A thrombospondins assemble into trimeric structures while the subgroup B thrombospondins function as pentamers.

The thrombospondins are secreted extracellular multisubunit glycoproteins that belong to the larger family of proteins termed matricellular proteins. Matricellular proteins are present in the ECM, however, they do not contribute to the primary structural functions of the ECM. Thrombospondins, like other matricellular proteins, integrate functions of the ECM with cells physically embedded in the ECM. To exert their effects matricellular proteins, such as the thrombospondins, interact with a number of cell surface receptors as well as with many other ECM structural proteins such as the collagens. Indeed, TSP1 has been shown to interact with at least 12 different cell adhesion molecules, several growth factors, as well as with numerous proteases.

The numerous roles for the thrombospondins include, but are not limited to, the regulation of endothelial cell apoptosis exerting anti-angiogenesis effects, promotion of smooth muscle cell adhesion, cell proliferation and migration, antagonism of nitric oxide (NO) signaling, maintenance of cardiac function and integrity, promotion of neurogenesis, regulation of bone mineralization/demineralization processes, regulation and modulation of immune functions, and processes of wound repair via regulation of fibrosis.

All five thrombospondins share significant amino acid sequence homology especially in the functional domains in the proteins. Using TSP1 as the prototype to define the domains of the subgroup A thrombospondins they contain three conserved repeats defined as the thrombospondin-1 type 1 repeats (TSP1 repeats; also known as thrombospondin structural repeats: TSR), three EGF-like domains, a von Willebrand factor type C repeat (VWFC repeat), an N-terminal domain, a C-terminal domain, and 13 calcium-binding type 3 repeats. The TSP1 repeat domain is found in numerous other proteins similar to the EFG-like domains that are found in numerous proteins.

The large family (19 members) of ADAMTS (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin repeats) proteins, that function as extracellular metalloproteases are, in fact, so-called due the presence of the TSP1 repeats. The N-terminal domain in TSP1 and TSP2 is a heparin-binding domain while the C-terminal domain is involved in cellular attachment. The subgroup B thrombospondins posses a distinct N-terminal domain, contain four EGF-like domains, and lack both the TSP1 repeats and the VWFC domain.

Glycosaminoglycans

The most abundant heteropolysaccharides in the body are the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). These molecules are long unbranched polysaccharides containing a repeating disaccharide unit. The disaccharide units contain either of two modified sugars, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) or N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), and a hexuronic acid such as glucuronate (GlcA) or iduronate (IdA). GAGs are highly negatively charged molecules, with extended conformation that imparts high viscosity to the solution in which they reside. GAGs are located primarily on the surface of cells or in the extracellular matrix but are also found in secretory vesicles in some types of cells.

Along with the high viscosity of GAGs comes low compressibility, which makes these molecules ideal for a lubricating fluid in the joints. At the same time, their rigidity provides structural integrity to cells and provides passageways between cells, allowing for cell migration. The specific GAGs of physiological significance are hyaluronic acid, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, heparin, heparan sulfate, and keratan sulfate. Although each of these GAGs has a predominant disaccharide component, heterogeneity does exist in the sugars present in the make-up of any given class of GAG.

As indicated in the Table below, and discussed in greater detail in the Glycosaminoglycans and Proteoglycans page, the various GAGs include the hyaluronates, chondroitin sulfates, keratan sulfates, dermatan sulfates, heparan sulfates, and heparins. Hyaluronic acid (also called hyaluronan) is unique among the GAGs in that it does not contain any sulfate and is not found covalently attached to proteins forming a proteoglycan. It is, however, a component of non-covalently formed complexes with proteoglycans in the ECM. Hyaluronic acid polymers are very large (with molecular weights of 100,000–10,000,000) and can displace a large volume of water. Indeed, the hyaluronans are the largest polysaccharides produced by vertebrate cells. The immense size of these molecules makes them excellent lubricators and shock absorbers in the joints.

Table of the Characteristics of GAGs

| GAG | Localization | Comments |

| Hyaluronate | synovial fluid, articular cartilage, skin, vitreous humor, ECM of loose connective tissue | large polymers; molecular weight can reach 1 million Daltons; high shock absorbing character; average person has 15 gm in body; 30% turned over every day; synthesized in plasma membrane by three hyaluronan synthases: HAS1, HAS2, and HAS3 |

| Chondroitin sulfate | cartilage, bone, heart valves | most abundant GAG; usually associated with protein to form proteoglycans; the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans form a family of molecules called lecticans and includes aggrecan, versican, brevican, and neurcan; major component of the ECM; loss of chondroitin sulfate from cartilage is a major cause of osteoarthritis |

| Heparan sulfate | basement membranes, components of cell surfaces | contains higher acetylated glucosamine than heparin; found associated with protein forming heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG); major HSPG forms are the syndecans and GPI-linked glypicans; HSPG binds numerous ligands such as fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF); HSPG also binds chylomicron remnants at the surface of hepatocytes; HSPG derived from endothelial cells act as anti-coagulant molecules |

| Heparin | component of intracellular granules of mast cells, lining the arteries of the lungs, liver and skin | more sulfated than heparan sulfates; clinically useful as an injectable anticoagulant although the precise role in vivo is likely defense against invading bacteria and foreign substances |

| Dermatan sulfate | skin, blood vessels, heart valves, tendons, lung | was originally referred to as chondroitin sulfate B which is a term no longer used; may function in coagulation, wound repair, fibrosis, and infection; excess accumulation in the mitral valve can result in mitral valve prolapse |

| Keratan sulfate | cornea, bone, cartilage aggregated with chondroitin sulfates | usually associated with protein forming proteoglycans; keratan sulfate proteoglycans include lumican, keratocan, fibromodulin, aggrecan, osteoadherin, and prolargin |

Proteoglycans

The majority of GAGs in the body are linked to core proteins, forming proteoglycans (also called mucopolysaccharides). The GAGs extend perpendicularly from the core in a brush-like structure. The linkage of GAGs to the protein core, in most but not proteoglycans, involves a specific tetrasaccharide linker composed of a glucuronic acid (GlcA) residue, two galactose (Gal) residues, and a xylose (Xyl) residue forming a structure such as: GAG(n)–GlcA–Gal–Gal–Xyl–Ser–protein. The tetrasaccharide linker is coupled to the protein core through an O-glycosidic bond to a Ser or Thr residue in the protein. The tetrasaccharide linker is most commonly seen in proteoglycans that contain heparins, heparan sulfates, dermatan sulfates, and chondroitin sulfates. Although most common, some GAGs are linked to the protein core of proteoglycans via a trisaccharide linkage that lacks the GlcA residue. In the case of the keratan sulfates, attachment of the sugar linker to the core protein can occur via O-linkage or via N-linkage. There are two major types of keratan sulfates (KSI and KSII) where KSI containing proteoglycans are formed via N-linkage and KSII containing proteoglycans are formed via O-linkage.

The protein cores of proteoglycans are rich in Ser and Thr residues, which allows multiple sites of polymeric GAG attachment. Following the formation of the tetrasaccharide linker if the next sugar added is N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) the resulting attached GAGs will be either heparins or heparan sulfates. If the next sugar is N-acetlygalactosamine (GalNAc) instead, then the attached GAGs will be either chondroitin sulfates or dermatan sulfates.

Essentially all mammalian cells have the capacity to synthesize proteoglycans and to secrete them into the ECM, or insert them into the plasma membrane, or to store them in secretory vesicles. The overall composition of a given type of ECM will ultimately determine the physical characteristics of the tissues it surrounds and also the many biological properties of the cells embedded in it. The proteoglycans found in the ECM interact with other ECM components keeping the level of fluidity high (forming a hydrated gel-like composition) and providing resistance to compressive forces. Different cell types produce different types of membrane-associated proteoglycans. Membrane proteoglycans have either a single membrane-spanning domain (a type I orientation) or they are linked to the membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. In addition, in some cells the proteoglycans are concentrated within secretory vesicles along with the other vesicle components. The role of vesicle proteoglycans is to help sequester and regulate the availability of positively charged vesicle components (e.g. proteases and bioactive amines such as neurotransmitters) via their interactions with the negatively charged polymeric GAG chains.

There exists a huge variability of proteoglycans in human tissues and cells (discussed in greater detail in the Glycosaminoglycans and Proteoglycans page). This variability is due to several factors including the large number of different proteoglycan core proteins and the ability add one or two different types of polymeric GAG chains to the protein core. Some proteoglycans contain only one GAG chain (e.g., decorin), whereas others can have several hundred GAG chains (e.g., aggrecan). Proteoglycan variability also results from the stoichiometry of GAG chain substitution. As an example, the proteoglycan, syndecan-1, has five attachment sites for GAGs, but not all of the sites are used equally. Another level of variability results from the fact that different cell types produce proteoglycans, from the same protein core, that exhibit differences in the number of GAG chains, the GAG chain polymeric length, and the arrangement of sulfated residues within the GAG chain.