Last Updated: May 20, 2025

Classic Galactosemia: Type 1

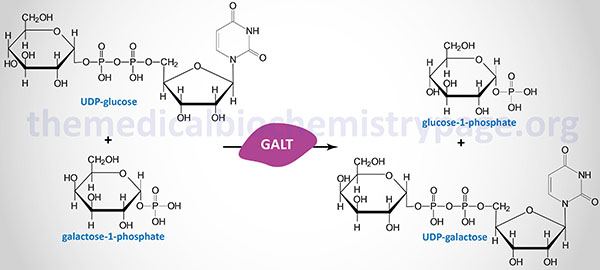

Classic galactosemia refers to a disorder arising from profound deficiency of the enzyme galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT) and is termed type 1 galactosemia. There are also classified clinical and biochemical variant forms of GALT deficient galactosemia. Classic galactosemia is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder and almost all afflicted individuals will present with symptoms in the neonatal period if undiagnosed. Type 1 galactosemia occurs with a frequency of between 1:40,000 to 1:60,000 live births in Western countries. When the frequency of galactosemia inheritance is assessed by anyone with erythrocyte GALT activity of <5% of normal and erythrocyte galactose-1-phosphate concentration >2mg/dL then the frequency reaches 1:10,000. Certain countries have higher levels of classic galactosemia inheritance than Western countries such as in Ireland where the frequency is close to 1:16,000 live births.

Classic galactosemia manifests by poor feeding behavior, a failure of neonates to thrive, bleeding problems, and E. coli-associated sepsis in untreated infants. In classic glactosemia, infants will exhibit vomiting and diarrhea rapidly following ingestion of lactose from breast milk or from lactose-containing formula. Due to the rapid progression of the symptoms, infants are sometimes erroneously termed lactose intolerant. However, the clinical distinction between classic lactose intolerance and classic galactosemia is quite profound. Newborn screening for classic galactosemia occurs in most states in the US and thus, the risks to newborns with this disease are drastically reduced. The typical prenatal test for galactosemia involves measurements of both erythrocyte GALT activity and erythrocyte levels of galactose-1-phosphate, the former being significantly reduced or absent, and the latter being elevated. Some prenatal tests only measure total blood galactose levels and in infants afflicted with a clinical or biochemical variant type 1 galactosemia, this assay may not be sufficient to detect any abnormality. In some cases of clinical or biochemical variant type 1 galactosemia a genetic test for GALT variant mutations may be necessary to confirm a diagnosis.

Clinical findings in infants with classic galactosemia who consume lactose or galactose containing meals include impaired liver function (which if left untreated leads to severe cirrhosis), hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated blood galactose, hypergalactosemia, hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, urinary galactitol excretion and hyperaminoaciduria. Unless controlled by exclusion of galactose from the diet, these galactosemias can go on to result in fatal liver failure, brain damage, and blindness. Blindness is due to the conversion of circulating galactose to the sugar alcohol galacitol, by an NADPH-dependent aldose reductase that is present in neural tissue and in the lens of the eye. At normal circulating levels of galactose this enzyme activity causes no pathological effects. However, a high concentration of galacitol in the lens causes osmotic swelling, with the resultant formation of cataracts and other negative symptoms within the eye.

Molecular Biology of Classic Galactosemia

The GALT gene is located on chromosome 9p13.3 and is composed of 11 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode distinct protein isoforms. Over 230 different mutations have been described in the gene encoding human GALT resulting in the three main forms (classic, clinical variant, biochemical variant) of type 1 galactosemia.

The most commonly detected mutation in Caucasians results in the Q188R allele defined by the substitution of arginine (R) for glutamine (Q) at amino acid 188 which lies close to the active site of the enzyme. Homozygotes for the Q188R allele show very little to no GALT activity in their erythrocytes. The majority of homozygotes are found to have no GALT activity, while others exhibit a low level of enzyme activity generally no more than 20% of the wild type.

Whereas the Q188R allele is most common in Caucasians, the most commonly detected mutations in European populations are K285N, S135L, and N314D. The K285N mutation is associated with 0% and 50% GALT activity in homozygous and heterozygous individuals, respectively.

The N314D mutation in the GALT gene is associated with two biochemical variants of type 1 galactosemia. The Los Angeles variant (designated D1) results solely from the N314D mutation. The Duarte variant (designated D2) is the result of both the N314D mutation in the coding region of the GALT gene as well as a GTCA deletion (-119 to -116) in the promoter region of the gene. The loss of those four nucleotides results in impairment of a positive regulatory domain in the GALT promoter. Very often a Duarte variant infant arises through the inheritance of a D2 allele from one parent and another pathogenic GALT mutation from the other parent. Patients with the Duarte variant form of type 1 galactosemia have erythrocyte GALT activity that is typically 14%–25% of that seen in non-affected individuals. Duarte variant infants can often be asymptomatic when given breast milk or lactose-containing formula. Any hyperbilirubinemia (evidenced as jaundice) in these Duarte infants will rapidly resolve when the lactose is removed from their diets.

Treatment of Classic Galactosemia

The principal treatment for infants with classic galactosemia, whose erythrocyte GALT activity is <10% of normal, is elimination of lactose from the diet. This lactose elimination regimen includes breast milk and all other milk products. Even on a galactose-restricted diet, GALT-deficient individuals exhibit urinary galacitol excretion and persistently elevated erythrocyte galactose-1-phosphate levels. In addition, even with life-long restriction of dietary galactose, many patients with classic galactosemia can develop serious long-term complications including speech defects, cognitive impairment, and in female patients the potential for premature follicular atresia resulting in ovarian insufficiency and sterility. Due to these persistent clinical complications, it is recommended that individuals with classic galactosemia undergo routine testing for the accumulation of erythrocyte galactose-1-phosphate, increased urinary galactose output, developmental delay, speech problems, and the formation of cataracts.

Type 2 Galactosemia

The second form of galactosemia, termed type 2, results from deficiency of galactokinase (GALK1). This form of galactosemia is quite rare with a frequency of <1:100,000 live births. Infants with GALK deficiency, who continue to consume a milk-based diet, accumulate abnormally high levels of galactose in their blood and tissues, similar to infants with classic galactosemia. Like classic galactosemia patients GALK deficiency often presents with cataracts that will resolve upon dietary restriction of galactose. However, unlike patients with classic galactosemia, patients with GALK deficiency who keep to a galactose restricted diet experience no known long-term complications. This difference is biochemically and clinically quite significant because it provides compelling evidence that it is not the accumulation of galactose, but rather galactose-1-phosphate (Gal-1P), or possibly some metabolic derivative Gal-1P, that is the primary cause of the complications, in addition to cataracts, that are observed in classic galactosemia patients and the more rare severe form of GALE deficiency.

Molecular Biology of Type 2 Galactosemia

The GALK1 gene is located on chromosome 17q25.1 and is composed of 9 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNA both of which encode the same 392 amino acid protein.

More than 30 different mutations have been found in the GALK1 gene in patients with type 2 galactosemia. The most common mutations in the GALK1 gene are missense mutations. Mutations in GALK1 are rare exhibiting a frequency of only 1 in 1,000,000. However, in ethnic Roma Gypsies of Eastern Europe the frequency of a particular mutation in codon 28 that changes the normal Pro codon to a Thr codon (P28T) is quite high, on the order of 1 in 50,000.

Type 3 Galactosemia

The third disorder of galactose metabolism, termed type 3 galactosemia, results from a deficiency of UDP-galactose-4-epimerase (GALE). Three different forms of this deficiency have been characterized. The peripheral form is the most common and manifests with decreased enzyme activity in red blood cells and leukocytes and normal or near normal levels in all other tissues. The peripheral form has a frequency of between 1 in 6,700 to 1 in 60,000 depending upon ethnicity. The intermediate form is associated with decreased enzyme activity in circulating blood cells and less than 50% in all other tissues. The severe generalized form is the most severe form and is associated with a profound generalized decrease of enzyme activity affecting multiple tissues and manifesting with symptoms similar to those seen with classic galactosemia. The severe generalized form is extremely rare with only six patients from three families having been described.

Molecular Biology of Type 3 Galactosemia

The GALE gene is located on chromosome 1p36.11 and is composed of 13 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode the same 348 amino acid protein.

Over 20 different mutations have been identified in the GALE gene in type 3 galactosemia patients. The most common mutation in the severe form of type 3 galactosemia is a missense mutation that changes codon 94 from a Val to a Met (V94M) codon.