Last Updated: February 18, 2026

Introduction to SCAD Deficiency

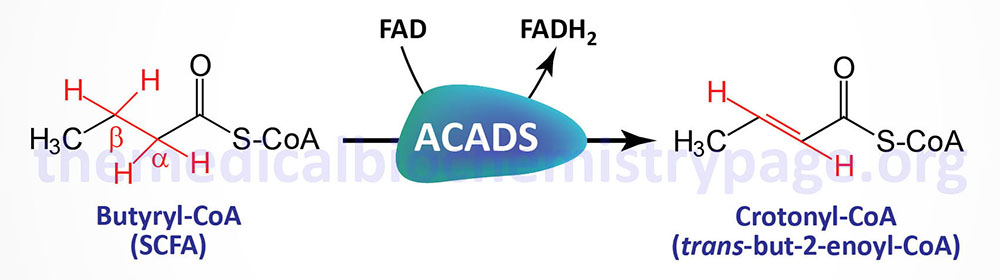

The acyl-CoA dehydrogenases are a family of enzymes involved in the first step of the mitochondrial β-oxidation of fatty acids. Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD), which is also called acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain (ACADS), is so called because of the size of its fatty acyl-CoA substrates. SCAD acts almost exclusively on the 4-carbon CoA, butyryl-CoA.

SCAD deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder that occurs with a frequency of approximately 1 in 35,000 to 1 in 50,000 live births. Although SCAD deficiency is a rare disorder, screening for the disease is part of the neonatal inherited disease screening protocols undertaken in US hospitals.

Molecular Biology of SCAD Deficiency

SCAD deficiency (SCADD) results from mutations in the ACADS gene. The ACADS gene is located on chromosome 1q24.31 and is composed of 11 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding precursor proteins of 412 amino acids (isoform 1) and 408 amino acids (isoform 2).

The majority of SCADD patients are homozygous or compound heterozygous for two common variants of the ACADS gene. At least 70 different inactivating ACADS mutations have been reported. Homozygosity is common for mutations at codon 171 where the encoded Arg is changed to Trp (R171W) and codon 209 where the encoded Gly is changed to Ser (G209S).

Mutations in the ACADS gene result in the accumulation of its substrate (butyryl-CoA) and the resultant alternative metabolic byproducts which includes butyryl-carnitine, the glycine-ester (butyryl-glycine), butyrate, and ethylmalonic acid (EMA). Testing for butyryl-carnitine in the blood and for EMA in the urine are considered the diagnostic biochemical markers for SCADD.

Clinical Features of SCAD Deficiency

SCAD deficiency has only very recently been described and molecularly characterized. The first case was reported in 1987 with the molecular genetics being characterized in 1990. The initial SCADD patient exhibited signs of lethargy, hypotonia, and circulatory problems with metabolic acidosis within the first week after birth. This infant exhibited normal growth and development without recurrences of the metabolic acidosis up until the age of 2 years, however, this patient later died.

Subsequent to this initial SCADD patient numerous other patients were identified. Based upon the findings in these other SCADD cases it was apparent that the disorder is associated with a wide spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms. Clinical signs and symptoms in SCADD patients generally present early in life, with almost all patients presenting under the age of 5 years.

The symptoms of SCADD include hypoglycemia, hypotonia, lethargy, myopathy, developmental delay, and epilepsy. Individual cases have been associated with dysmorphic features, vomiting, failure to thrive, hepatic dysfunction after premature delivery, and bilateral optic atrophy. SCADD patient outcomes are also highly variable with some who fully recovered, to those exhibiting a slowly progressing disease, while others have died in infancy.

Treatment of SCAD Deficiency

The primary goal of treatment for SCAD deficiency is to reduce the production of toxic intermediates from accumulating from the abnormal metabolism of butyryl-CoA. Treatment with oral carnitine increases the removal of these toxic intermediates. In addition to oral carnitine, SCADD patients should consume a low fat diet and ensure adequate intake of vitamin B2 (riboflavin) as this serves as the precursor for the cofactor (FAD) required for the function of the acyl-CoA dehydrogenases.