Last Updated: October 30, 2025

Introduction to Porphyria Cutanea Tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is an autosomal dominant disorder that is a member of a family of disorders referred to as the porphyrias. Each disease in this family results from deficiencies in a specific enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of heme (also called the porphyrin pathway). The term porphyria is derived from the Greek term porphura which means “purple pigment” in reference to the coloration of body fluids in individuals suffering from a disease that is now known was in fact PCT. The occurrence of PCT in the United States is approximately 1 in 25,000.

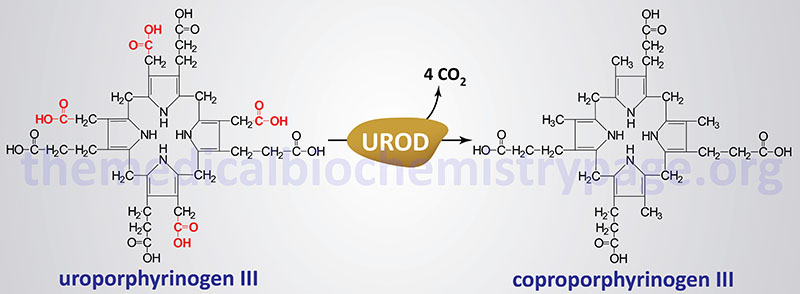

The porphyrias are classified on the basis of the tissue that is the predominant site of accumulation of metabolic intermediates. These classifications are “hepatic” or “erythroid”. Each disease is also further characterized as being acute or cutaneous dependent upon the major clinical features of the disease. PCT results from deficiencies in uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD) in the liver and other tissues of the body. PCT is the most commonly occurring porphyria of any type and it is classified as a hepatic porphyria. PCT has also been called symptomatic porphyria or idiosyncratic porphyria.

PCT is the result of deficiency in the activity of the heme biosynthetic enzyme, uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase. PCT is classified as an acquired porphyria given that even in individuals who inherit autosomal dominant mutations in the gene (UROD) encoding uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, other susceptibility factors are needed to cause clinical symptoms. Deficiency in uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase activity can be acquired in the presence of iron overload, alcohol consumption, smoking, and many other susceptibility factors with as many as 80% of all PCT cases being sporadic.

PCT is divided into two major subtypes: type 1 is the sporadic type with near normal levels of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase protein, type 2 is the familial autosomal dominant type where individuals possess around 50% of normal uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase activity. Type 1 PCT accounts for approximately 80% of all PCT patients worldwide. Both types of PCT have similar clinical features. However, only type 2 PCT has been directly associated with mutations in the UROD gene and the disorder is an autosomal dominant inherited trait with the characteristic of incomplete penetrance. Type 1 PCT is the result of multifactorial effects on the level of activity of the UROD encoded enzyme within hepatocytes.

Hepatoerythropoietic porphyria (HEP) is the homozygous dominant form of type 2 PCT. HEP receives its name because the deficiency in UROD leads to the accumulation of porphyrins in both the liver and bone marrow. The symptoms of HEP are similar to those of congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP).

Molecular Biology of PCT

The uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase gene (UROD) is located on chromosome 1p34.1 covering just 3 kb and encompassing 10 exons that encode a protein is 367 amino acids.

At least 110 different mutations have been identified in the UROD gene resulting in type 2 autosomal dominant PCT. These mutations include missense , nonsense, and splicing mutations, as well as deletions and insertion. About 60% of the UROD mutations in type 2 PCT patients are missense mutations. Approximately 70% of all mutations in the UROD gene are found between exons 5 and 10. Most of the identified mutations are unique to a given PCT patient.

Clinical Features of PCT

PCT is a late onset disease with most affected individuals manifesting symptoms in the 5th to 6th decade of life. The symptoms of PCT are characterized by blistering skin lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin. Because of this characteristic feature, PCT is strongly indicated in persons who develop skin lesions, particularly on the back of the hands and back of the neck, upon exposure to sunlight. In addition to blistering skin lesions, the typical sign of PCT is that which was originally described by Hippocrates, dark red or purple coloration of the urine. The reddish coloration of the urine in PCT patients is the result of the excretion of large amounts of uroporphyrin. Uroporphyrin is the product of hepatic CYP1A2 action on uroporphyrinogen which accumulates due to the reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase.

Symptom of PCT can be precipitated by excess hepatic iron, alcohol consumption, hepatitis C infection, estrogen administration, HIV infection, and by induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes such as is typically seen in smokers. Alcohol consumption is a major susceptibility factor in PCT being associated with 60% to 90% of all cases of PCT. Persons harboring mutations in the HFE1 gene which results in hemochromatosis are also highly predisposed to PCT.

The blistering lesions of PCT rupture easily and heal slowly. The poor healing of the wounds can lead to secondary infections. Due to repeated blistering and rupture, the skin becomes thickened, scarred and calcified resembling features of scleroderma (referred to as pseudoscleroderma). In addition to the cutaneous clinical features of PCT, there are also hepatic abnormalities that can be evidenced by abnormal liver function tests. Histologically the liver of PCT patients shows necrosis, inflammation, increased iron deposition and increased fatty deposits. In spite of these hepatic findings cirrhosis is only reported in one third of PCT patients.

HEP usually presents in infancy or childhood with red urine, blistering skin lesions and scarring. Hemolytic anemia, associated with splenomegaly, is commonly present in these patients due in part to the deposition of porphyrins in the bone marrow. As indicated above, these symptoms are similar to those seen in congenital erythropoietic porphyria, CEP.

Treatment of PCT

The specific treatment regimen for PCT patients depends upon several factors. All patients need protection from sunlight while they are in the symptomatic phase. It is important to ensure that elimination of known susceptibility factors is adhered to. These factors include alcohol consumption, smoking, oral estrogen use, and hepatotoxins.

Reductions in total body iron stores and liver iron content may be necessary and is accomplished by phlebotomy and administration of low dose anti-malarial agents (chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine). Iron chelation therapy with the use of deferasirox, deferiprone, or desferrioxamine, may be necessary if phlebotomy is contraindicated.

Other porphyrias that cause blistering skin lesions, such as HEP, are not responsive to the same treatment regimen and, therefore, it is important to make a correct diagnosis of PCT before treatment is initiated.