Last Updated: September 17, 2025

Lipid Digestion

Utilization of dietary lipids requires that they first be absorbed through the intestine. As these molecules are oils they would essentially be insoluble in the aqueous intestinal environment. Dietary lipid digestion and absorption are also covered in the Digestion and Digestive Processes page.

Solubilization (emulsification) of dietary lipid is accomplished, initially, via the agitation action as food passes through the stomach and then the emulsification process continues within the intestine via interaction with the bile salts that are synthesized in the liver and secreted from the gallbladder.

Dietary lipids, in the form of triglycerides (TG; or triacylglycerides, TAG), phospholipids, and cholesterol, are digested by various lipases. The bulk of dietary lipids in the human diet are in the form of triglycerides. The lipases found in the gastrointestinal tract include one originally identified as lingual lipase (secreted by acinar cells of von Ebner glands of the tongue), gastric lipase (encoded by the LIPF gene and secreted by Chief cells of the stomach), pancreatic lipase (PNLIP gene), and pancreatic lipase-related protein 2 (PNLIPRP2 gene). These enzymes generate free fatty acids and a mixture of mono- and diglycerides from dietary triglycerides.

Lingual lipase and gastric lipase are both derived from the lipase F, gastric (LIPF) gene and together constitute the acid lipases. The acidic lipases function essentially only in the acidic environment of the stomach. However, evidence suggests that lingual lipase functions within the mouth allowing for the ability to taste non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA). The acid lipases are distinct from pancreatic lipases in that they do not require a lipid-bile acid interface for activity nor do they require the presence of the accessory protein, colipase.

Pancreatic lipases, on the other hand, only function in the neutral pH environment generated in the small intestine by the secretion of pancreatic bicarbonate (HCO3–). Also, pancreatic lipases require the presence of colipase and a lipid-bile acid interface for their activity. The role of colipase in pancreatic lipase function is to anchor the lipase to the surface of an emulsified lipid droplet and to prevent it from being removed by bile salts. Pancreatic lipase degrades triglycerides at the sn-1 (C1) and sn-3 (C3) positions sequentially to generate 1,2-diacylglycerides (DAG) and 2-monoacylglycerides (MAG). Phospholipids are degraded at the sn-2 (C2) position by pancreatic phospholipase A2 releasing a free fatty acid and the lysophospholipid.

Table of the Major Lipases of Lipid Digestion and Plasma Lipid Metabolism

| Lipase Name | Gene and Structure | Primary Source | Functions / Comments |

| carboxy ester lipase, CEL | CEL: 9q34.13; 11 exons | pancreas | encoded precursor protein is 756 amino acids; hydrolyzes cholesteryl esters, tri-, di-, and monoglycerides, phospholipids, lysophospholipids, and ceramides; predominant site of expression is pancreas, also expressed, albeit at extremely low levels, in liver, intestine, and macrophages; participates in chylomicron assembly in intestinal enterocytes and their secretion |

| lysosomal acid lipase, LAL | LIPA: 10q23.31: 10 exons | lysosomes | enzyme is also called cholesterol ester hydrolase; three alternatively spliced mRNAs encode two distinct protein isoforms (399 and 283 amino acid precursor proteins); hydrolyzes cholesteryl esters and triglycerides |

| hepatic lipase | LIPC: 15q21.3; 15 exons | hepatocytes | encoded precursor protein is 499 amino acids; maturation requires activity of lipase maturation factor 1 (LMF1); protein is secreted from hepatocytes and binds to heparan-sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) on surface of hepatocytes and endothelial cells; released to plasma via interactions involving apoA-II-enriched HDL; major substrates are IDL and triglyceride-rich HDL; activity is inhibited by angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) |

| hormone sensitive lipase, HSL | LIPE: 19q13.2; 15 exons | adipocytes; testis | initially described as an epinephrine- and glucagon-responsive gene encoding an adipose tissue triglyceride lipase; alternative 5′ exon utilization results in a short form (775 amino acids) and a long form (1076 amino acids) of the enzyme; the short form is exclusive to adipose tissue, the long form was originally identified as a testis-specific isoform; pancreatic β-cells utilize an alternative translational start site generating a protein of 818 amino acids; primary substrates in adipose tissue are diglycerides; known to hydrolyze triglycerides and monoglycerides (albeit inefficiently), and cholesteryl esters, as well as other lipid and water soluble substrates; activities detailed in the next section |

| gastric/lingual lipase | LIPF: 10q23.31; 11 exons | gastric Chief cells | four alternatively spliced mRNAs; four protein isoforms; acidic lipase responsible for hydrolysis of dietary triglycerides within the stomach |

| endothelial lipase | LIPG: 18q21.1; 12 exons | endothelial cells | two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two protein isoforms (500 and 426 amino acid precursor proteins); remains associated with endothelial cells; maturation requires activity of lipase maturation factor 1 (LMF1); functions primarily as a phospholipase A1 (PLA1) type hydrolase with principal substrates being phosphatidylcholines; participates in HDL metabolism; activity inhibited by the hepatocyte-derived plasma protein, angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) |

| lipoprotein lipase | LPL: 8p21.3; 10 exons | adipocytes, cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle cells | 475 amino acid precursor protein; primarily expressed in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and cardiac capillary endothelial cells; functions as a homodimeric enzyme; synthesized in cells of the tissues via the ER secretory pathway; transferred across the subendothelial spaces to capillary endothelial cells through interaction with endothelial cell glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored HDL binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1); LPL remains attached to endothelial cell surfaces through its interaction with GPIHBP1; primary substrates are triglyceride-rich chylomicrons and VLDL; activity inhibited by the hepatocyte-derived plasma protein, angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) and by ANGPTL4 |

| monoglyceride lipase | MGLL: 3q21.3; 12 exons | ten alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding nine distinct protein isoforms; in addition to hydrolyzing monoglycerides, this serine hydrolase also metabolizes the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG); activities detailed in the next section | |

| pancreatic lipase | PNLIP: 10q25.3; 13 exons | pancreas | 465 amino acid precursor protein; hydrolyzes dietary triglycerides contained in bile acid micelles within the small intestine; requires colipase, which is secreted by the pancreas, for activity |

| pancreatic lipase related protein 2 | PNLIPRP2: 10q25.3; 13 exons | pancreas | due to allelic variants there are coding and non-coding version of this gene; the coding version produces a 470 amino acid precursor protein; hydrolyzes dietary triglycerides, phospholipids, and galactolipids (from plants); human genome has two additional related genes PNLIPRP1 and PNLPRP3; protein encoded by PNLIPRP1 does not possess lipase activity |

Following absorption of the products of pancreatic lipase by the intestinal enterocytes, the re-synthesis of triglycerides occurs. The triglycerides are then solubilized in lipoprotein complexes (complexes of lipid and protein) called chylomicrons. A chylomicron contains lipid droplets surrounded by the more polar phospholipids and finally a layer of proteins. Triglycerides synthesized in the liver are packaged into VLDL and released into the blood directly. Chylomicrons from the intestine are first released into the lymphatic system and then into the blood at the left subclavian vein for delivery of dietary fatty acids to the various tissues for storage (adipose tissue) or production of energy through oxidation (primarily skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle).

There are exceptions to the packaging of dietary lipids into chylomicrons within the intestinal enterocytes. The exceptions are short-chain (less than 6 carbon atoms) and medium-chain (6 to 12 carbons) fatty acids. Although the bulk of dietary fatty acids are long-chain (14 to 22 carbon atoms) fatty acids in triglycerides (abbreviated LCT) some triglycerides contain medium-chain fatty acids (abbreviated MCT). When MCT are hydrolyzed by pancreatic lipases the released fatty acids easily diffuse into the intestinal enterocytes and are passed directly to the portal circulation, bypassing the lymphatic system. Most, if not all, of the short-chain fatty acids (butyrate, propionate, and acetate) that are absorbed from the intestines are produced through the action of gut microbiota (bacteria) metabolism of soluble and insoluble fiber in the diet and these short-chain fatty acids also directly enter the blood from the intestinal enterocytes.

The triglyceride components of VLDL and chylomicrons are hydrolyzed to free fatty acids and glycerol in the capillaries of tissues such as adipose tissue, heart, and skeletal muscle by the actions of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and in the liver through the actions of hepatic triglyceride lipase [HTGL; encoded by the lipase C, hepatic (LIPC) gene]. The free fatty acids are then absorbed by the cells and the glycerol is returned, via the blood, to the liver (principal site) and kidneys. Within the liver the glycerol can then be converted to the glycolytic intermediate dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and incorporated into the gluconeogenesis pathway or phosphorylated by glycerol kinase to glycerol-3-phosphate for reuse in triglyceride synthesis.

The classification of blood lipoprotein complexes is distinguished based upon the density of the different lipoproteins. As lipid is less dense than protein, the lower the density of lipoprotein the less protein there is in the particle.

Mobilization of Fat Stores

The primary sources of fatty acids for oxidation are dietary and mobilization from cellular stores. Fatty acids from the diet are absorbed from the duodenum, packaged into lipoprotein particles called chylomicrons within intestinal enterocytes and then delivered to cells of the body via transport in the blood. Fatty acids are stored in the form of triglycerides within all cells but predominantly within adipose tissue.

In response to energy demands, the fatty acids of stored triglycerides can be mobilized for use by peripheral tissues. The release of metabolic energy, in the form of fatty acids, is controlled by a complex series of interrelated cascades that result in the activation of triglyceride hydrolysis.

The primary intracellular lipases are adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL, also called desnutrin), hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), and lipase A (LIPA; also called lysosomal acid lipase, LAL). LIPA is the most important lipase involved in lysosomal lipid metabolism as evidenced by the fact that LIPA deficiency results in the significant accumulation of cholesteryl esters in tissues such as the spleen and liver. LIPA deficiency is commonly called Wolman disease or cholesterol ester storage disease.

Adipose Triglyceride Lipase: ATGL

ATGL/desnutrin belongs to the family of patatin domain-containing proteins that consists of nine members in humans. The patatin domain was originally discovered in lipid hydrolases of certain plants and named after the most abundant protein of the potato tuber, patatin. Because some members of the family act as phospholipases, the proteins were originally called patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein A1 to A9 (PNPLA1–PNPLA9). ATGL (designated PNPLA2 in the patatin domain nomenclature) preferentially hydrolyzes triglycerides.

The human gene encoding ATGL is PNPLA2. The PNPLA2 gene is located on chromosome 11p15.5 and is composed of 10 exons encoding a 504 amino acids protein.

In analogy with patatin, the active site of ATGL contains an unusual catalytic dyad (Ser47 and Asp166) within the patatin domain in the N-terminal half of the enzyme. The C-terminal half of the enzyme comprises the regulatory functions and also contains a predicted hydrophobic region involved in lipid droplet (LD) binding.

ATGL expression and enzyme activity are both under complex regulation. Expression of ATGL is induced by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists, glucocorticoids, and fasting. In addition, activation of the FoxO1 transcription factor by SIRT1-mediated deacetylation activates lipolysis by increasing ATGL expression. Conversely, silencing of SIRT1 has the opposite effect. Increased insulin release and food intake both result in decreased expression of ATGL. Reductions in ATGL expression have also been shown to be associated with mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)-dependent signaling.

The level of lipase activity of ATGL (as well as HSL) does not always correlate to the level of expression of the gene. For example, TNFα activity reduces both ATGL and HSL expression at the level of the gene but induces increased lipase activity of pre-existing enzyme resulting in fatty acid and glycerol release from triglycerides. Similarly, the use of non-selective beta blockers (e.g. isoproterenol) results in the same type of gene inhibition with enzyme activation. The discrepancy between ATGL and HSL mRNA levels and enzyme activities is the result of extensive post-translational regulation of both ATGL and HSL.

There are two serine residues in ATGL that are subject to phosphorylation. Unlike phosphorylation of HSL (described below), ATGL phosphorylation is not PKA-dependent. In the mouse, it has been shown that AMPK phosphorylates ATGL resulting in increased lipase activity. However, it is important to point out that there remains a level of controversy as to the role of AMPK in the regulation of the activity of ATGL since induction, inhibition, and no effects results have been published.

Phosphorylation of ATGL is also carried out by Ca2+–calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II, CaMKII. Within the liver this CAMKII mediated phosphorylation results in increased ATGL activity which, in turn, leads to increased rates of intrahepatic lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation. CaMKII is actually a family of four serine/threonine kinases, CaMKIIα, CaMKIIβ, CaMKIIγ, and CaMKIIδ, each of which is encoded by a separate gene.

The activity of CaMKII, which is regulated by cytosolic Ca2+, can be increased under conditions of abnormal mitochondrial calcium uptake. The major inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) localized transporter responsible for mitochondrial uptake of calcium is the MCU (mitochondrial calcium uniporter). When mitochondrial calcium uptake is impaired in the liver there is increased cytosolic Ca2+ which results in increased activity of CaMKII. The increased phosphorylation of ATGL by CaMKII, under these conditions, leads to increased fatty acid oxidation and secondarily to increased gluconeogenesis.

In addition to phosphorylation regulating ATGL activity, the enzyme requires a coactivator protein for full lipase activity. The gene encoding this coactivator was originally identified as Comparative Gene Identification-58, CGI-58. The term comparative gene identification relates to the use of computational methods to identify protein sequences highly conserved across various species and CGI-58 was originally discovered in a screen comparing the proteomes of humans and C. elegans.

The official name for CGI-58 is α/β hydrolase domain-containing protein-5, lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (also identified as 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase) owing to the presence of an α/β hydrolase domain commonly found in esterases, thioesterases, and lipases. The enzyme is encoded by the ABHD5 gene.

The ABHD5 gene is located on chromosome 3p21.33 and is composed of 10 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode three distinct protein isoforms.

It is unlikely that the ABHD5 protein possesses hydrolase activity because an asparagine residue is found in the catalytic domain where other hydrolases have a nucleophilic serine residue that is required for enzymatic activity. In addition to functioning as an ATGL coactivator, ABHD5 has also been shown to possess enzymatic activity as an acyl-CoA-dependent acylglycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (AGPAT). The physiological significance of this activity is currently unknown but it may be involved in the regulation of phosphatidic acid or lysophosphatidic acid signaling.

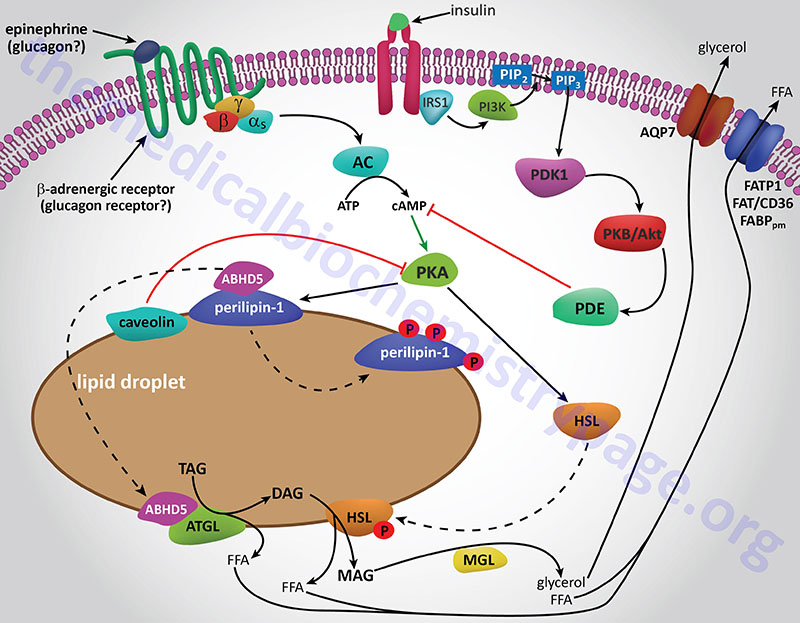

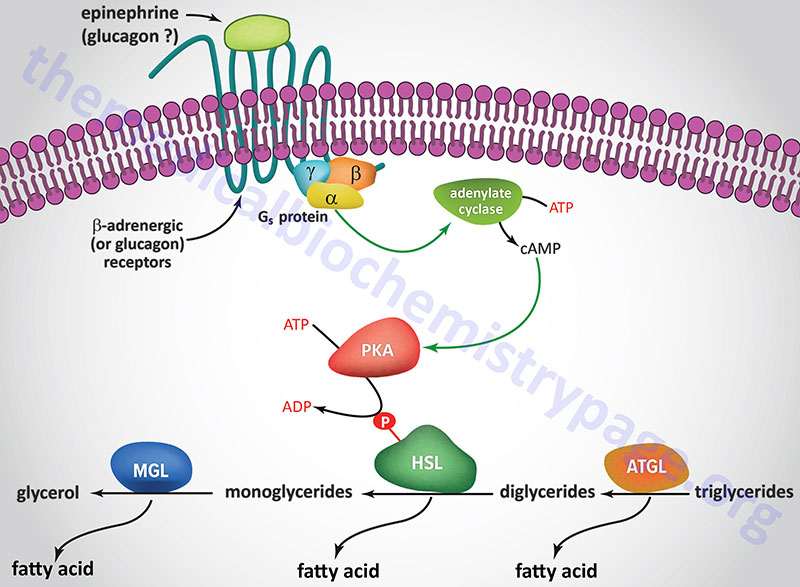

Additional proteins associated with lipid droplets (LD) in adipocytes participate in the ABHD5-mediated regulation of ATGL. In resting adipocytes of both WAT and BAT, the LD protein perilipin-1 interacts with ABHD5, preventing its binding to and, induction of ATGL. Following β-adrenergic stimulation of WAT, PKA phosphorylates perilipin-1 at multiple sites resulting in the release of ABHD5 which in turn, binds to and stimulates ATGL. This demonstrates that β-adrenergic stimulation of PKA induces ATGL activity, not by direct phosphorylation of ATGL itself, but through phosphorylation of perilipin-1. This model of ATGL regulation is evident from frameshift mutants that have been identified in the human perilipin-1 gene. These mutations are identified as V398fs and L404fs indicating that the frame shift occurs at valine 398 and leucine 404, respectively. Each of these mutant perilipin-1 proteins fails to bind ABHD5, resulting in unrestrained lipolysis, partial lipodystrophy, hypertriglyceridemia, and insulin resistance.

In non-adipose tissues with high rates of triglyceride hydrolysis, such as skeletal muscle and liver, regulation of ATGL activity occurs via a mechanism distinct from that in adipose tissue. In these tissues, perilipin-1 is replaced by perilipin-5. During fasting, perilipin-5 recruits both ATGL and ABHD5 to LD by direct binding of the enzyme and its coactivator. Data indicates that perilipin-5 is involved in the interaction of LD with mitochondria and thereby inhibits ATGL-mediated triglyceride hydrolysis.

Recently, a specific protein inhibitor for ATGL was isolated from white blood cells, specifically mononuclear cells. This protein was originally identified as being involved in the regulation of the G0 to G1 transition of the cell cycle. This protein was, therefore, called G0G1 switch protein 2 (encoded by the G0S2 gene). The protein is found in numerous tissues, with highest concentrations in adipose tissue and liver.

The G0S2 gene is located on chromosome 1q32.2 and is composed of 2 exons that encode a protein of 103 amino acids.

In adipose tissue G0S2 expression is very low during fasting but increases after feeding. Conversely, fasting or PPARα-agonists increase hepatic G0S2 expression. The protein has been shown to localize to LD, cytoplasm, ER, and mitochondria. These different subcellular localizations likely relate to multiple functions for G0S2 in regulating lipolysis, the cell cycle, and, possibly, apoptosis via its ability to interact with the mitochondrial antiapoptotic factor Bcl-2. With respect to ATGL regulation, the binding of the enzyme to LD and subsequent regulation is dependent on a physical interaction between the N-terminal region of G0S2 and the patatin domain of ATGL.

The delivery of ATGL to LD requires functional vesicular transport. When essential protein components of the transport machinery are defective or missing, such as ADP-ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1), small GTP-binding protein 1 (SAR1), the guanine-nucleotide exchange factor Golgi-Brefeldin A resistance factor (GBF1), or the coatamer proteins coat-complex I (COPI) and COPII, ATGL translocation to LD is blocked and the enzyme remains associated with the ER.

Disorders Associated with ATGL and ABHD5

Mutations in the PNPLA2 gene result in the lipid storage myopathy (LSM) identified as neutral lipid storage disease with myopathy, NLSDM. Mutations in the ABHD5 gene result in the lipid storage myopathy (LSM) identified as neutral lipid storage disease with ichthyosis, NLSDI, also known as Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome. NLSDI is associated with massive triglyceride storage and defective long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation. The characteristic features of NLSDI are dry, scaly skin evident at birth as well as a progressive fatty infiltration of the liver.

Hormone-Sensitive Lipase: HSL

A landmark study published in 1964 demonstrated that a lipolytic activity present in adipose tissue was induced by hormonal stimulation. This work described the isolation and characterization of both HSL and monoglyceride lipase (MGL). This original study demonstrated that HSL had a higher level of activity as a diglyceride hydrolase than as a triglyceride hydrolase. Nevertheless, it became dogma that HSL was rate-limiting for the catabolism of fat stores in adipose and many non-adipose tissues.

However, when HSL-deficient mice were produced and shown to efficiently hydrolyze triglycerides the model began to emerge demonstrating ATGL, and not HSL, to be rate-limiting for adipose tissue triglyceride hydrolysis. HSL-deficient mice do not accumulate triglycerides in either adipose or non-adipose tissues, but they do accumulate large amounts of diglycerides in many tissues. This indicated for the first time that HSL was more important as a diglyceride hydrolase than a triglyceride hydrolase. It is now accepted that ATGL is responsible for the initial step of lipolysis in human adipocytes, and that HSL is rate-limiting for the catabolism of diglycerides. HSL not only hydrolyzes diglycerides but is also active at hydrolyzing ester bonds of many other lipids including triglycerides, monoglycerides, cholesteryl esters, retinyl esters, and short-chain carbonic acid esters.

The gene encoding HSL (official symbol: LIPE for lipase E, hormone sensitive) is located on chromosome 19q13.2 and is composed of 15 exons. Alternative exon usage results in tissue-specific differences in mRNA and protein size. In adipose tissue the HSL protein is composed of 775 amino acids, whereas the testicular form is composed of 1,076 amino acids. The larger HSL isoform found in testis is due to the inclusion of a novel exon located 16 kb upstream of the exons that encode the adipose tissue (and other tissues) form of HSL.

The expression profile of HSL, within adipocytes, essentially mirrors that of ATGL. Highest mRNA and protein concentrations are found in WAT and BAT with low levels of expression found in muscle, testis, steroidogenic tissues, and pancreatic islets as well as several other tissues.

Functional studies on the enzyme have identified an N-terminal lipid-binding region, the α/β hydrolase fold domain including the catalytic triad, and the regulatory module containing all known phosphorylation sites important for regulation of enzyme activity.

HSL and ATGL share many regulatory similarities yet the mechanisms of the regulatory processes differ markedly between the two enzymes. In adipose tissue, HSL enzyme activity is strongly induced by β-adrenergic stimulation, conversely insulin has a strong inhibitory effect. While β-adrenergic stimulation regulates ATGL primarily via recruitment of the coactivator ABHD5, HSL is a major target for PKA-mediated phosphorylation. Additional kinases, including AMPK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase I (CaMKI), also phosphorylate HSL to modulate the activity of the enzyme. HSL has at least five potential phosphorylation sites, of which S660 and S663 appear to be particularly important for hydrolytic activity.

Phosphorylation of HSL affects enzyme activity only moderately resulting in an approximate 2-fold increase in hydrolytic activity. For full activation, HSL must gain access to LD, which, in adipose tissue, is mediated by perilipin-1. In addition to phosphorylating HSL, PKA also phosphorylates perilipin-1 on six consensus serine residues. The result of these phosphorylations is the binding of HSL to the N-terminal region of perilipin-1. This protein-protein interaction is the means by which HSL gains access to LD. The net effect, of HSL-phosphorylation and enzyme translocation to LD, coupled with ATGL activation by ABHD5, leads to a more than 100-fold increase in triglyceride hydrolysis in adipocytes.

Additional factors modulate the activation of HSL and ATGL. One such factor is nuclear receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140; encoded by the NRIP1 gene) which induces lipolysis by binding to perilipin-1, increasing HSL translocation to LD, and activating ATGL via ABHD5 dissociation from perilipin-1. In non-adipose tissues, such as skeletal muscle, HSL is activated by phosphorylation in response to epinephrine (β-adrenergic receptor-mediated activation of PKA) and muscle contraction (calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum). Since skeletal muscles lack perilipin-1 it has not yet been determined which alternative mechanisms regulate HSL access to LD.

Insulin-mediated deactivation of lipolysis is associated with transcriptional downregulation of ATGL and HSL expression. Additionally, insulin signaling results in phosphorylation and activation of various phosphodiesterase (PDE) isoforms (predominantly PDE3B) by PKB/AKT leading to PDE-catalyzed hydrolysis of cAMP which in turn results in reduced activation of PKA. These actions turn off lipolysis by preventing phosphorylation of both HSL and perilipin-1, activation and translocation of HSL, and activation of ATGL by ABHD5. In addition to its peripheral action, insulin also functions within the sympathetic nervous system to inhibit lipolysis in WAT. Increased insulin levels in the brain inhibit HSL and perilipin phosphorylation which results in reduced HSL and ATGL activities.

Monoglyceride lipase: MGL

MGL is considered to be the rate-limiting enzyme for the breakdown of monoglycerides that are the result of both extracellular and intracellular lipolysis pathways. The extracellular generation of monoglycerides is the result of the action of endothelial cell lipoprotein lipase (LPL) on lipoprotein particle-associated triglycerides. Intracellular hydrolysis of triglycerides by ATGL and HSL, as well as intracellular phospholipid hydrolysis by phospholipase C (PLC) and membrane-associated diglyceride lipase α and β results in the generation of MGL substrates.

The gene (MGLL) that encodes MGL is located on chromosome 3q21.3 and is composed of 12 exons that generate ten alternatively spliced mRNAs, that collectively encode nine distinct protein isoforms. MGL has been shown to localize to lipid droplets (LD), cell membranes, and the cytosol. The enzyme is ubiquitously expressed with highest levels of expression in adipose tissue. MGL shares homology with esterases, lysophospholipases, and haloperoxidases. The enzyme contains a consensus GXSXG motif within a catalytic triad that is typical of lipases and esterases.

MGL is critically important for efficient degradation of monoglycerides since it has been shown in mouse models that lack of MGL impairs lipolysis and is associated with increased MG levels in adipose and non-adipose tissues alike. MGL has received particular attention in recent years due to the discovery that the enzyme is responsible for the inactivation of 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) which is an endogenous cannabinoid monoglyceride (endocannabinoid).

For more information on the activities of ATGL, HSL and other lipases regulating triglyceride levels in adipocytes visit the Adipose Tissue: Not Just Fat page.

In contrast to the hormonal activation of adenylate cyclase and (subsequently) hormone-sensitive lipase in adipocytes, the mobilization of fat from adipose tissue is inhibited by numerous stimuli. The most significant inhibition is that exerted upon adenylate cyclase by insulin. When an individual is in the well fed state, insulin released from the pancreas prevents the inappropriate mobilization of stored fat. Instead, any excess fat and carbohydrate are incorporated into the triglyceride pool within adipose tissue.

Cellular Uptake of Fatty Acids

When fatty acids are released from adipose tissue stores they enter the circulation as free fatty acids (FFAs) and are bound to albumin for transport to peripheral tissues. When the fatty acid–albumin complexes interact with cell surfaces the dissociation of the fatty acid from albumin represents the first step of the cellular uptake process. Uptake of fatty acids by cells involves membrane proteins with high affinity for fatty acids.

There are several members of the fatty acid receptor family including fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36), plasma membrane-associated fatty acid-binding protein (FABPpm), and several fatty acid transport proteins (FATP). The FATP are a family of at least six fatty acid transport proteins (FATP1–FATP6) that are also members of the solute carrier family of transporters. The FATP facilitate the uptake of very long-chain (VLCFA) and long-chain fatty acids (LCFA).

FAT/CD36 is encoded by the CD36 gene. The CD36 encoded protein was originally identified a platelet receptor for thrombospondin and mutations in the CD36 gene are associated with platelet glycoprotein deficiency. The CD36 encoded protein is also known as scavenger receptor B3 (SCARB3 or SR-B3). With respect to fatty acid metabolism, FAT/CD36 is the major protein involved in the uptake of fatty acids by adipocytes, skeletal muscle myocytes, and heart cardiomyocytes. The localization of FAT/CD36 to the plasma membrane is facilitated by palmitoylation in the Golgi apparatus. The palmitoylation of FAT/CD36 is catalyzed by a member of the DHCC (Asp-His-Cys-Cys) domain-containing palmitoyltransferase encoded by the ZDHCC5 (zinc finger DHHC-type palmitoyltransferase 5) gene.

Within the plasma membrane FAT/CD36 is associated with the tyrosine kinase, LYN (LCK/YES-related). When fatty acids interact with FAT/CD36, the kinase activity of LYN is activated which then phosphorylates the ZDHHC5 encoded enzyme preventing palmitoylation of FAT/CD36. Under these conditions FAT/CD36 is depalmitoylated, a reaction catalyzed by the LYPLA1 (lysophospholipase 1) gene. The depalmitoylation of FAT/CD36 triggers endocytosis resulting in the internalization of the fatty acids.

Table of Mammalian Fatty Acid Transporters – Acyl-CoA Synthetases

| Fat Transporter | Comments |

| FAT/CD36 | fatty acid translocase; FAT is also known as CD36 which is a member of the scavenger receptor class (class B scavenger receptors) of receptors that bind lipids and lipoproteins of the LDL family; is a major regulator of ferroptosis via its interactions with the GPCR, GPR56 (encoded by the ADGRG1 gene); the CD36 gene is located on chromosome 7q21.11 and composed of 22 exons that generate 15 alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode six distinct isoforms of the protein |

| FABPpm | plasma membrane-associated fatty acid-binding protein; originally characterized as a plasma membrane-associated fatty acid transporter this protein was later demonstrated to be the mitochondrial isoform of glutamate-oxalate transaminase (gene symbol: GOT2); gene located on chromosome 16q21 and is composed of 10 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding precursor proteins of 430 amino acids (isoform 1) and 387 amino acids (isoform 2) |

| FATP1 | FATP1 is SLC27A1; FATP1 is also known as acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 5 (ACSVL5); highest levels of expression in adipose tissue, skeletal and heart muscle; the SLC27A1 gene is located on chromosome 19p13.11 and is composed of 16 exons encoding a 646 amino acid protein |

| FATP2 | FATP2 is SLC27A2; FATP2 is also known as acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 1 (ACSVL1) as well as very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (VLCS); highest levels of expression in liver and kidney; present in peroxisome and microsomal membranes; the SLC27A2 gene is located on chromosome 15q21.2 composed of 10 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode precursor proteins of 620 amino acids (isoform 1) and 567 amino acids (isoform 2) |

| FATP3 | FATP3 is SLC27A3; FATP3 is also known as acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 3 (ACSVL3); the SLC27A3 gene is located on chromosome 1q21.3 and is composed of 10 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode precursor proteins of 683 amino acids (isoform 1) and 648 amino acids (isoform 2) |

| FATP4 | FATP4 is SLC27A4; FATP4 is also known as acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 4 (ACSVL4); is the major intestinal long-chain fatty acid transporter; the SLC27A4 gene is located on chromosome 9q34.11 and is composed of 14 exons that encode a 643 amino acid protein |

| FATP5 | FATP5 is SLC27A5; FATP5 is also known as acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 6 (ACSVL6), also as very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase-related protein (VLACSR), also as very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase homolog 2 (VLCSH2), and also as bile acid-CoA synthetase (BACS); ER-associated enzyme; highest levels of expression in the liver; capable of activating 24- and 26-carbon VLCFAs; catalyzes the activation of bile acids via formation of bile acid-CoA thioesters which then undergo conjugation with glycine and taurine (this activity is identified as BACS); the SLC27A5 gene is located on chromosome 19q13.43 and is composed of 11 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding proteins of 690 amino acids (isoform 1) and 606 amino acids (isoform 2) |

| FATP6 | FATP6 is SLC27A6; FATP6 is also known as acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 2 (ACSVL2), very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase homolog 1 (VLCSH1); expressed at highest levels in the heart; protein only detected in heart and testis; exhibits a preference for the transport of palmitic acid and linoleic acid, does not transport fatty acids less than 10 carbons long; the SLC27A6 gene is located on chromosome 5q23.3 and is composed of 112 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs all of which encode the same 619 amino acid protein |

The result of the interaction of fatty acids with plasma membrane receptors/binding proteins is a transmembrane concentration gradient. At the plasma membrane the apparent pKa of the fatty acid shifts from about 4.5 in aqueous solutions to about 7.6. This pKa change is independent of fatty acid type. As a consequence, about half of the fatty acids are present in the un-ionized form. This local environment effect promotes a transfer (flip-flop) of uncharged fatty acids from the outer leaflet across the phospholipid bilayer.

At the cytosolic surface of the plasma membrane, fatty acids can associate with the cytosolic fatty acid binding protein (FABPc) or with caveolin-1. Caveolin-1 is a constituent of caveolae (Latin for little caves) which are specialized “lipid rafts” present in flask-shaped indentations in the plasma membranes of many cells types that perform a number of signaling functions by serving as lipid delivery vehicles for subcellular organelles. In order that the fatty acids that are taken up to be directed to the various metabolic pathways (e.g. oxidation or triglyceride synthesis) they must be activated to acyl-CoA.

Members of the fatty acid transport protein (FATP) family have been shown to possess acyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) activity. Activation of fatty acids by FATPs occurs at the highly conserved cytosolic AMP-binding site of these proteins. The overall process of cellular fatty acid uptake and subsequent intracellular utilization represents a continuum of dissociation from albumin by interaction with the membrane-associated transport proteins, binding to FABPc and caveolin-1 at the cytosolic plasma membrane, activation to acyl-CoA (in many cases via FATP action) followed by intracellular trafficking via FABPc and/or caveolae to sites of metabolic disposition.

Roles of Intracellular Fatty Acid Binding Proteins, FABP

Fatty acid binding proteins (FABP) represent a family of intracellular lipid-binding proteins whose functions are to reversibly bind intracellular hydrophobic ligands and transport the bound ligand throughout the various cellular compartments, including the peroxisomes, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and nucleus.

FABP have broad binding characteristics which includes the ability to bind long-chain (C16–C20) fatty acids (LCFA), eicosanoids, bile salts, and peroxisome proliferators. There are currently nine well characterized FABP genes in the human genome, four of which (FABP4, FABP5, FABP9, and FABP12) are located in the same region of the q arm of chromosome 8 (8q21.13). The gene (PMP2) encoding peripheral myelin protein 2, also identified as FABP8, is also located on chromosome 8q21.13.

Each of these FABP was originally named for the tissue in which it was first isolated and characterized or in which it predominates. However, many of these FABP are expressed in numerous tissues. The nine FABP genes are members of the large fatty acid binding protein family of genes that included the genes encoding cellular retinoic acid binding proteins (CRABP) and those encoding retinol binding proteins (RBP).

Expression of a particular FABP gene directly reflects the lipid metabolic capacity of that tissue. In high lipid metabolizing tissues, such as the liver, adipose tissue, and the heart, the expressed FABP can account for 1%–5% of total soluble cytosolic proteins. The expression of FABP in the cell is essential for the binding of hydrophobic ligands, particularly free fatty acids, in order to reduce the detergent-like properties of high concentrations of fatty acids, thereby keeping them soluble. FABP are critical to the process of lipid trafficking within cells to the various cellular compartments where they will be stored, oxidized, utilized for membrane synthesis, and for their roles in the activation of nuclear receptors. With respect to the latter function, it has been shown that FABP are involved in the targeting of fatty acids to transcription factors of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family.

In addition to their importance in intracellular lipid trafficking, many FABP interact with phospholipid-rich membranes and bind eicosanoid intermediates protecting these substrates against peroxidation strongly implicating these proteins in antioxidant-type behavior.

Table of Fatty Acid Binding Proteins

| FABP | Alternate Names | Tissue Location | Functions / Comments |

| FABP1 (L-FABP) | Z protein, hepatic FABP, heme-binding protein | liver, intestine, pancreas, kidney, lung, stomach | represents up to 5% of hepatocyte cytosolic protein; unique ability to bind multiple ligands at once; in addition to various free fatty acids FABP1 binds fatty acyl-carnitines, intermediates in glyceride synthesis, lysophospholipids, cholesterol, bile acids, prostaglandins, lipoxygenase products, retinoids, heme, and bilirubin; FABP1 also binds numerous xenobiotic drugs such as NSAIDs, fibrates, beta blockers, and benzodiazepines; the FABP1 gene is located on chromosome 2p11.2 and is composed of 4 exons encoding a 127 amino acid protein |

| FABP2 (I-FABP) | gut FABP, gFABP | intestine | mediates dietary fat absorption of free long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs); the FABP2 gene is located on chromosome 4q26 and is composed of 4 exons encoding a 132 amino acid protein; a polymorphism in codon 54 that causes a substitution of alanine for threonine (A54T) is associated with increased serum triglyceride accumulation, weight gain, and insulin resistance |

| FABP3 (H-FABP) | O-FABP, mammary-derived growth inhibitor, MDGI | skeletal and heart muscle, brain, kidney, lung, stomach, testes, placenta, ovary, brown adipose tissue (BAT), adrenal glands, mammary glands | makes up 4%–8% of cytosolic protein in the heart; major function is to traffic fatty acids to the mitochondria for oxidation; also binds non-prostanoid oxygenated fatty acids; measurement of protein in the blood is considered an early marker for myocardial infarct; may also be a marker for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) by measurement of levels in the cerebrospinal fluid; the FABP3 gene is located on chromosome 1p35.2 and is composed of 5 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding proteins of 144 amino acids (isoform 1) and 133 amino acids (isoform 2) |

| FABP4 (A-FABP) | adipocyte protein 2, aP2 | adipocytes and macrophages of adipose tissue, dendritic cells | specific binding capacity for LCFAs; is a marker for adipocyte maturation; modulates the activity of HSL through direct interaction; macrophage FABP4 modulates inflammatory responses; recently demonstrated to be a secreted adipokine involved in regulating hepatic glucose production; the FABP4 gene is located on chromosome 8q21.13 and composed of 4 exons that encode a 132 amino acid protein |

| FABP5 (E-FABP) | psoriasis-associated FABP (PA-FABP); keratinocyte-type FABP (KFABP) | skin, brain, stomach, intestines, kidney, liver, lung, heart, skeletal muscle, tongue, adipocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, testes, retina, placenta, spleen | physiological ligands not completely determined; in vitro the protein binds stearic acid with high affinity while having reduced affinity for unsaturated fatty acids; interacts with HSL like FABP4; the FABP5 gene is located on chromosome 8q21.13 and is composed of 4 exons that encode a 135 amino acid protein |

| FABP6 (Il-FABP) | ileal lipid-binding protein (ILBP); gastrotropin; intestinal bile acid-binding protein (I-BABP) | predominantly the ileum, also expressed at low levels in stomach, adrenal glands, ovary | involved in enterohepatic circulation of bile acids; binds bile acids with highest affinity then fatty acids; interacts with the ileal bile acid transporter protein; the FABP6 gene is located on chromosome 5q33.3 and is composed of 7 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode proteins of 177 amino acids (isoform 1) and 128 amino acids (isoform 2) |

| FABP7 (B-FABP) | brain lipid-binding protein (BLBP) | brain, glial cells, mammary glands, retina | grey matter neurons do not express FABP7; highest affinity for long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) particularly EPA and DHA; also binds oleic acid and arachidonic acid but does not bind palmitic acid or retinoic acid; the FABP7 gene is located on chromosome 6q22.31 and is composed of 5 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a distinct protein isoform |

| FABP8 PMP2, M-FABP | peripheral myelin protein 2; myelin P2 protein | Schwann cells, peripheral nervous system | only member of the FABP family that is stably attached to the membrane; present on the cytoplasmic side of compact myelin membranes; binds LCFAs; thought to be involved in stabilizing myelin membranes; official gene symbol is PMP2; the PMP2 gene is located on chromosome 8q21.13 and is composed of 4 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding proteins of 132 amino acids (isoform 1) and 60 amino acids (isoform 2) |

| FABP9 (T-FABP) | testes lipid-binding protein (TLBP); | testes, mammary glands, salivary glands | precise functions not clearly defined; thought to be involved in protection of fatty acids in sperm from oxidation; the FABP9 gene is located on chromosome 8q21.13 and is composed of 4 exons that encode a 132 amino acid protein |

| FABP12 | testes, lung, duodenum | the FABP12 gene is located on chromosome 8q21.13 and is composed of 7 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs |

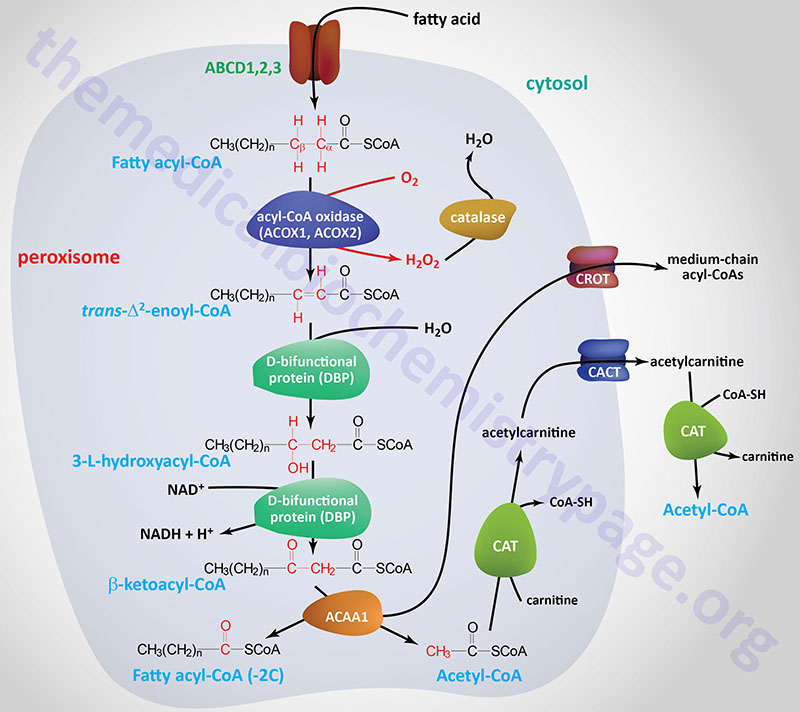

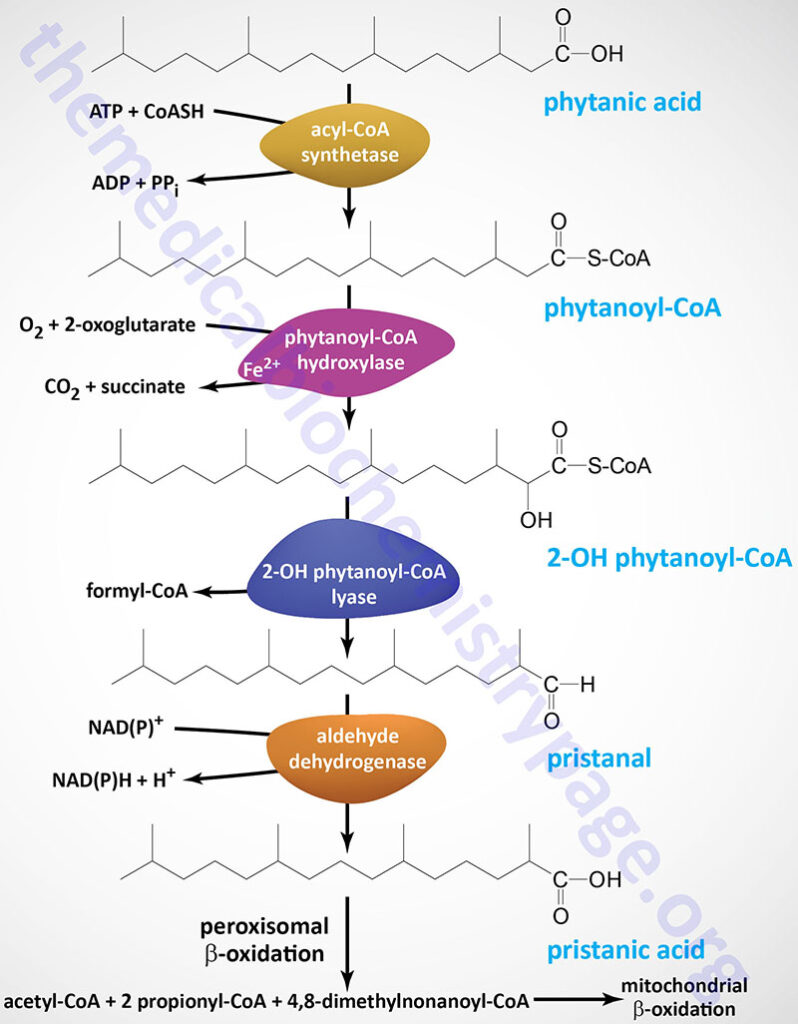

Fatty Acid Activation

Oxidation of fatty acids occurs in the mitochondria and the peroxisomes (see below). Fatty acids of between 4–8 and between 6–16 carbon atoms in length, referred to as short- and medium-chain fatty acids (SCFA and MCFA), respectively, are oxidized exclusively in the mitochondria. Long-chain fatty acids (LCFA: 10–18 carbons long) are oxidized in both the mitochondria and the peroxisomes with the peroxisomes exhibiting preference for 14-carbon and longer LCFA. Very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFA: C18–C26; often designated as any fatty acid of 22 carbons and longer) are preferentially oxidized in the peroxisomes. However, given that peroxisomes are unable to completely oxidize fatty acids, the chain shortened free fatty acids, or their carnitine esters, are released and taken up by the mitochondria for complete oxidation to CO2 and H2O.

Long-chain fatty acids must be activated in the cytoplasm before being oxidized in the mitochondria. Medium-chain and short-chain fatty acids are activated within the matrix of the mitochondria. Fatty acid activation is catalyzed by fatty acyl-CoA synthetases (also called acyl-CoA ligases or thiokinases). The net result of this activation process is the consumption of two molar equivalents of ATP.

Humans express at least 26 acyl-CoA synthetases with several of these enzymes also being involved in fatty acid transport into cells (FATP1–FATP6) as indicated in the Table above in the Cellular Uptake of Fatty Acids section. The various acyl-CoA synthetases exhibit different substrate specificities, subcellular localization, and tissue distribution. Additional members of the family are the long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases, the medium-chain acyl-CoA synthetases, the short-chain acyl-CoA synthetases, and the bubblegum family acyl-CoA synthetases.

Fatty acid + ATP + CoA → Acyl-CoA + PPi + AMP

Table of the Mammalian Acyl-CoA Synthetase Family

| Gene Symbol | Aliases | Location | Enzyme name / Comments |

| AACS | 12q24.31 | acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase; primary enzyme for the conversion of acetoacetate to acetoacetyl-CoA; gene composed of 19 exons that encode a 672 amino acid protein | |

| AASDH | 4q12 | aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase; also called acyl-CoA synthetase family member 4, isoform 2; gene composed of 17 exons that encode a protein of 992 amino acids | |

| ACSBG1 | 15q25.1 | acyl-CoA synthetase bubblegum family member 1; gene composed of 19 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs; involved in brain VLCFA metabolism and myelogenesis | |

| ACSBG2 | 19p13.3 | acyl-CoA synthetase bubblegum family member 2; gene composed of 16 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding three distinct isoforms; expression restricted to the testis | |

| ACSF2 | 17q21.33 | acyl-CoA synthetase family member 2; gene composed of 19 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding five distinct isoforms | |

| ACSF3 | 16q24.3 | acyl-CoA synthetase family member 3; mitochondrial protein, high affinity for methylmalonate and malonate; gene composed of 17 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two distinct isoforms | |

| ACSS1 | 20p11.21 | acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 1; mitochondrial protein primarily responsible for generation of mitochondrial acetyl-CoA from acetate; is also responsible for the generation of crotonyl-CoA from crotonate which is involved in the process of protein lysine crotonylation; gene composed of 15 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode four distinct isoforms | |

| ACSS2 | 20q11.22 | acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 2; cytosolic protein primarily responsible for generation of acetyl-CoA from acetate; is also responsible for the generation of lactoyl-CoA from lactate which is involved in the process of protein lysine lactylation which includes histone lactylation; gene expression controlled by SREBP; gene composed of 22 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding three distinct isoforms | |

| ACSS3 | 12q21.31 | acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 3; gene composed of 19 exons that encode a 686 amino acid precursor protein | |

| ACSM1 | 16p12.3 | acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 1; mitochondrial protein; gene composed of 18 exons that encode a 577 amino acid protein | |

| ACSM2A | 16p12.3 | acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 2A; mitochondrial protein; gene composed of 15 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two distinct isoforms | |

| ACSM2B | 16p12.3 | acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 2B; mitochondrial protein; gene composed of 16 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding the same protein | |

| ACSM3 | 16p13.11 | acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 3; mitochondrial protein; gene composed of 15 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode two distinct isoforms | |

| ACSM4 | 12p13.31 | acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 4; mitochondrial protein; gene composed of 13 exons that encode a 580 amino acid precursor protein | |

| ACSM5 | 16p12.3 | acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 5; mitochondrial protein; gene composed of 14 exons that encode a 579 amino acid precursor protein | |

| ACSL1 | 4q35.1 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1; substrate preference for fatty acids of 16–20 carbons; expression highest in heart, liver, and adipose tissue; involved in activation of inflammasomes in neutrophils during sepsis; activity reduces the level of lipid oxidation and increases the resistance of cells to ferroptosis; gene composed of 28 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding four distinct isoforms | |

| ACSL3 | 2q36.1 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3; involved in the production of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA); substrate preference for myristic (C14:0), arachidonic (C20:4), and eicosapentaenoic, EPA (C20:5) acids; highly expressed in the brain, testes, and skeletal muscle; localized in the Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), peroxisomes, and mitochondrial outer membrane; may be involved in resistance to ferroptosis; gene composed of 17 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding the same protein | |

| ACSL4 | Xq23 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; involved in the production of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA); expression highest in adrenal gland, ovary, testis, and brain; localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria, plasma membrane, and peroxisomes; substrate preference for fatty acids of 16–20 carbons; enhances possibility for plasma membrane lipid peroxidation and therefore to an increase in the potential for ferroptosis; involved in activation of inflammasomes in neutrophils during sepsis; gene composed of 17 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two distinct isoforms; preferentially recognizes arachidonic acid as substrate | |

| ACSL5 | 10q25.2 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 5; expressed in liver, small intestine, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, spleen, lung, and uterus; localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondrial outer membrane; substrate preference for palmitic (C16:0), palmitoleic (C16:1), oleic (C18:1), and linoleic (C18:2) acids; gene composed of 23 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two distinct isoforms; functions as tumor suppressor in a cytotoxic T-cell (CTL)-dependent manner | |

| ACSL6 | 5q31 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 6; near exclusive expression in the brain; substrate preference for docosahexaenoic acid, DHA (C22:6); required for the enrichment of DHA in the brain; gene composed of 23 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding six distinct isoforms | |

| SLC27A1 | FATP1, ACSVL5 | 19p13.11 | solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 1; also known as fatty acid transport protein 1 and acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 5; see details above |

| SLC27A2 | FATP2, ACSVL1 | 15q21.2 | solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 2; also known as fatty acid transport protein 2 and acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 1; see details above |

| SLC27A3 | FATP3, ACSVL3 | 1q21.3 | solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 3; also known as fatty acid transport protein 3 and acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 3; see details above |

| SLC27A4 | FATP4, ACSVL4 | 9q34.11 | solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 4; also known as fatty acid transport protein 4 and acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 4; see details above |

| SLC27A5 | FATP5, ACSVL6 | 19q13.43 | solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 5; also known as fatty acid transport protein 5 and acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 6; see details above |

| SLC27A6 | FATP6, ACSVL2 | 5q23.3 | solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 6; also known as fatty acid transport protein 6 and acyl-CoA synthetase very long-chain family, member 2; see details above |

Fatty Acid Deactivation

Once a fatty acid is esterified to coenzyme A forming an acyl-CoA, its fate is not destined for oxidation in the mitochondria or the peroxisomes. Fatty acyl-CoA molecules are substrates for a family of enzymes called acyl-CoA thioesterases (ACOT). The products of ACOT activity are free fatty acids and CoASH. The action of ACOT enzymes serves to deactivate fatty acids.

There are two classes of ACOT enzymes, identified as type I and type II. The type I acyl-CoA thioesterases are characterized by a molecular mass of approximately 40 kDa and they exhibit positive responses to peroxisome proliferator treatment. Type I ACOT enzymes belong to the large α/β-hydrolase family of enzymes that includes lipases and esterases. The type II acyl-CoA thioesterases are characterized by a molecular mass of approximately 110–150 kDa and they exhibit variable responses peroxisome proliferator treatment. The type II ACOT enzymes, despite possessing limited amino acid sequence similarity, do have structural features in common. One distinctive feature is termed the hot-dog domain. The hot-dog domain consists of a seven-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (the “bun”) that wraps around a hydrophobic five-turn α-helical region (the “hot dog”), and a layer comprising loops over the helix referred to as the “condiments”.

Humans express 12 genes that encode enzymes that possess acyl-CoA thioesterase activity. There are 10 genes identified by the ACOT nomenclature, ACOT1, ACOT2, ACOT4, ACOT6, ACOT7, ACOT8, ACOT9, ACOT11, ACOT12, and ACOT13 and two genes that are designated by the thioesterase superfamily nomenclature, THEM4 and THEM5. The THEM5 gene has also been identified as ACOT15. Several ACOT genes are also identified with the THEM nomenclature with ACOT11 being identified as THEM1 and ACOT13 being identified as THEM2.

The ACOT11 and ACOT12 encoded proteins possess multiple functional domains with one domain being the thioesterase domain and the other being a START (STeroidogenic Acute Regulatory protein-related lipid Transfer (START) domain. As such ACOT11 has also been identified as STARD14 and ACOT12 has been identified as STARD15.

The ACOT1, ACOT2, and ACOT4 encoded enzymes are type I acyl-CoA thioesterases while the ACOT7, ACOT8, ACOT9, ACOT11, ACOT12, ACOT13, THEM4, and THEM5 encoded enzymes are type II acyl-CoA thioesterases.

Four genes, ACOT1, ACOT2, ACOT4, and ACOT6 are clustered on chromosome 14q24.3. the ACOT6 encoded protein possesses a catalytic site but it is unclear whether the protein has a functional enzymatic activity.

Expression of the ACOT1, ACOT2, and ACOT4 genes is highest in adipose tissue, liver, heart, and kidney. The ACOT1 encoded enzyme is localized to the cytosol and exhibits substrate specificity for long-chain (C12-C20) saturated- and monounsaturated acyl-CoAs. The ACOT2 encoded enzyme is targeted to the mitochondrial matrix where it exhibits substrate specificity for long-chain fatty acyl-CoAs. The ACOT4 encoded enzyme possesses a type I peroxisomal targeting sequence and exhibits substrate specificity for short-chain dicarboxylic acyl-CoA esters, particularly succinyl-CoA, and medium- to long-chain acyl-CoAs.

Mitochondrial (beta) β-Oxidation Reactions

Fatty Acid Transport into Mitochondria

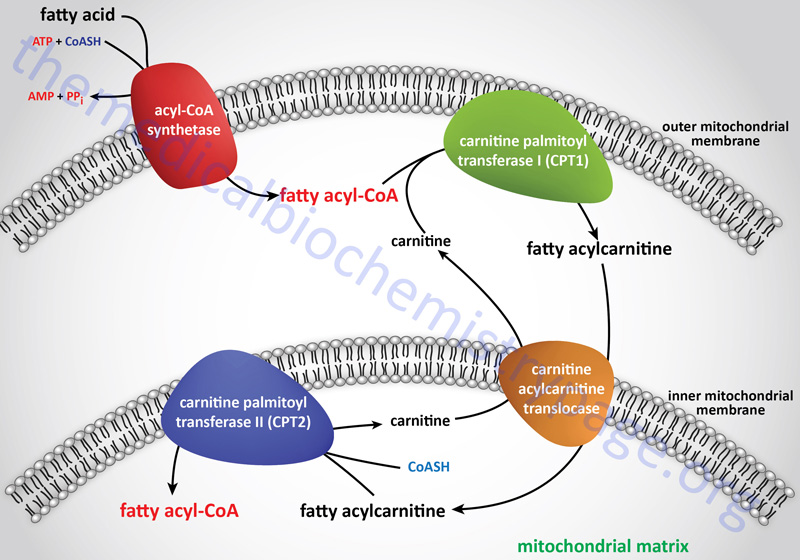

Short-chain and medium-chain fatty acids require no specific transport mechanism to enter the mitochondria for oxidation and, as indicated earlier, are activated by CoA attachment within the mitochondrial matrix. Also, because dietary short-chain and medium-chain fatty acids directly enter the portal circulation (they are not packaged into chylomicrons) they are rapidly oxidized within the liver.

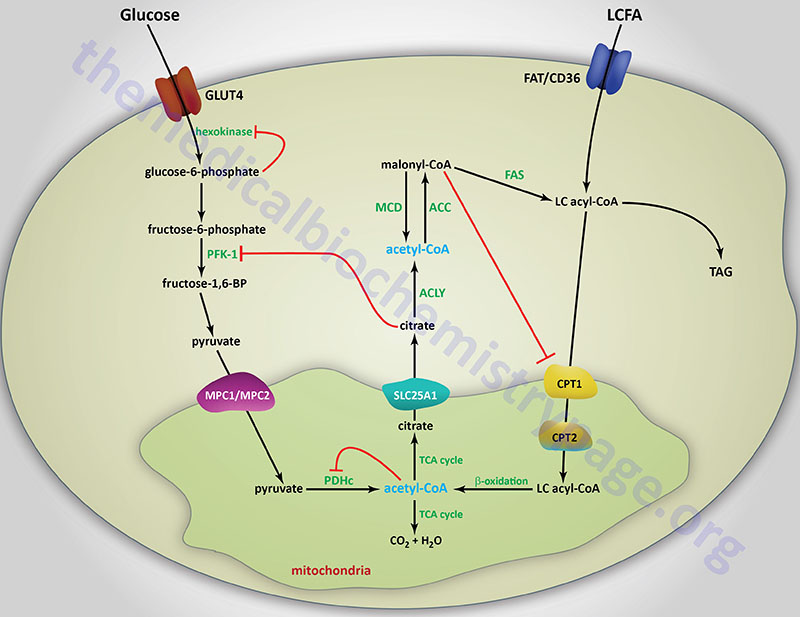

Long-chain fatty acids, present in the triglycerides of chylomicrons, or VLDL, or as free fatty acids released from adipose tissue, require a specific mitochondrial transport mechanism to be oxidized. The transport of long-chain fatty acyl-CoAs into the mitochondria is accomplished via an acyl-carnitine intermediate, which itself is generated by the action of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1 or CPT-I), an enzyme that resides in the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Carnitine Transport

The carnitine that is used by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) is transported into cells by the plasma membrane localized transporter encoded by the SLC22A5 gene. The SLC22A5 encoded transporter is commonly identified as organic zwitterion/cation transporter 2 (OCTN2). OCTN2 is the only carnitine transporter localized to the plasma membrane and as such represents the major transporter for cellular uptake of carnitine.

The SLC22A5 gene is located on chromosome 5q31.1 and is composed of 11 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode proteins of 581 amino acids (isoform a) and 557 amino acids (isoform b). Expression of the SLC22A5 gene is ubiquitous but the highest levels are seen in the small intestines and kidneys.

Free carnitine is transported out of the mitochondria, to the cytosol, via the action of the carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase, CACT. The CACT transporter is also capable of transporting acyl-carnitine molecules from the cytosol into the mitochondria, as described in the next section.

Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1)

There are three CPT1 genes in humans identified as CPT1A, CPT1B, and CPT1C. Expression of CPT1A predominates in the liver and is thus, referred to as the liver isoform. CPT1B expression predominates in skeletal muscle and is thus, referred to as the muscle isoform. CPT1C expression is exclusive to the brain and testes.

The CPT1A gene is located on chromosome 11q13.2 and consists of 22 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding isoform 1 (773 amino acids) and isoform 2 (756 amino acids).

The CPT1B gene is located on chromosome 22q13.33 and consists of 21 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs, all of which yield two distinct isoforms of the enzyme. Isoform a is 772 amino acids and isoform c is 738 amino acids.

The CPT1C gene is located on chromosome 19q13.33 and consists of 24 exons that generate eleven alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode five different protein isoforms.

The activity of CPT1C is distinct from those of CPT1A and CPT1B in that it does not act on the same types of fatty acyl-CoAs that are substrates for the latter two enzymes, nor does it participate in the mobilization of fatty acids into the mitochondria. CPT1C does exhibit high-affinity for malonyl-CoA binding. Within the hypothalamus, brain CPT1C serves as a sensor of nutrient availability by binding malonyl-CoA which triggers a reduction in the release of the appetite promoting neuropeptides, neuropeptide Y (NPY) and Agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and an increase the release of the appetite suppressing neuropeptides, α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART). The net effect of increased hypothalamic malonyl-CoA binding to CPT1C is, therefore, satiety and appetite suppression.

Once a fatty acylcarnitine is generated at the outer mitochondrial membrane it is transported into the mitochondria through the action of carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase, CACT. The CACT transporter is a member of the SLC family of transporters and as such is encoded by the SLC25A20 gene. The carnitine acylcarnitine translocase is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it facilitates acylcarnitine transport across the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes in exchange for free carnitine.

The SLC25A20 gene is located on chromosome 3p21.31 and is composed of 9 exons that encode a 301 amino acid protein.

Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2)

Following CACT-mediated transfer of the CPT1-generated fatty acylcarnitines across the inner mitochondrial membrane, the fatty acyl-carnitine molecules are acted on by the inner mitochondrial membrane-associated carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2 or CPT-II) regenerating the fatty acyl-CoA molecules.

The CPT2 gene is located on chromosome 1p32.3 and consists of 5 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs. These mRNAs encode precursor proteins of 658 amino acids (isoform 1) and 635 amino acids (isoform 2).

Additional Carnitine Acyltransferases

In addition to the genes of the CPT family of carnitine acyltransferases, humans express two additional carnitine acyltransferases. The two additional enzymes are carnitine O-acetyltransferase encoded by the CRAT gene and carnitine octanoyltransferase encoded by the CROT gene.

The CRAT gene is located on chromosome 9q34.11 and is composed of 18 exons that generate seven alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode six distinct protein isoforms. The different CRAT mRNAs encode enzymes that are found in the mitochondrial matrix, the peroxisomes, and the nucleus. The substrate specificity of CRAT is for short-chain acyl-CoA esters.

The CROT gene is located on chromosome 7q21.12 and is composed of 21 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode three distinct protein isoforms.

The CROT encoded enzyme is found in the peroxisomes where it has substrate preference for medium-chain acyl-CoAs. The major substrate for the CROT enzyme is 4,8-dimethylnonanoyl-CoA. The function of the CROT enzyme is to participate in the transport of medium- and long-chain fatty acyl-CoA molecules out of the peroxisomes to the cytosol where they can then be transported into the mitochondria.

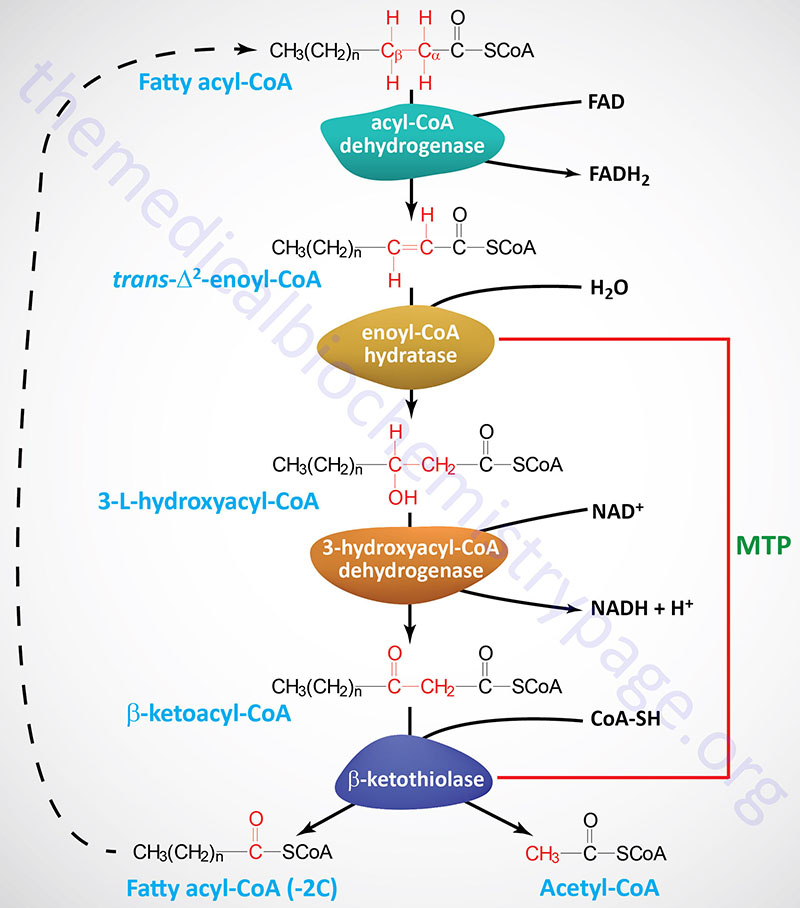

Processes of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation

The process of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation is termed β-oxidation since it occurs through the sequential removal of 2-carbon units by oxidation at the β-carbon position, relative to the carboxylic acid group, of the fatty acyl-CoA molecule. The oxidation of fatty acids and lipids in the peroxisomes (see below) also occurs via a process of β-oxidation but the enzymes are distinct from those used within the mitochondria.

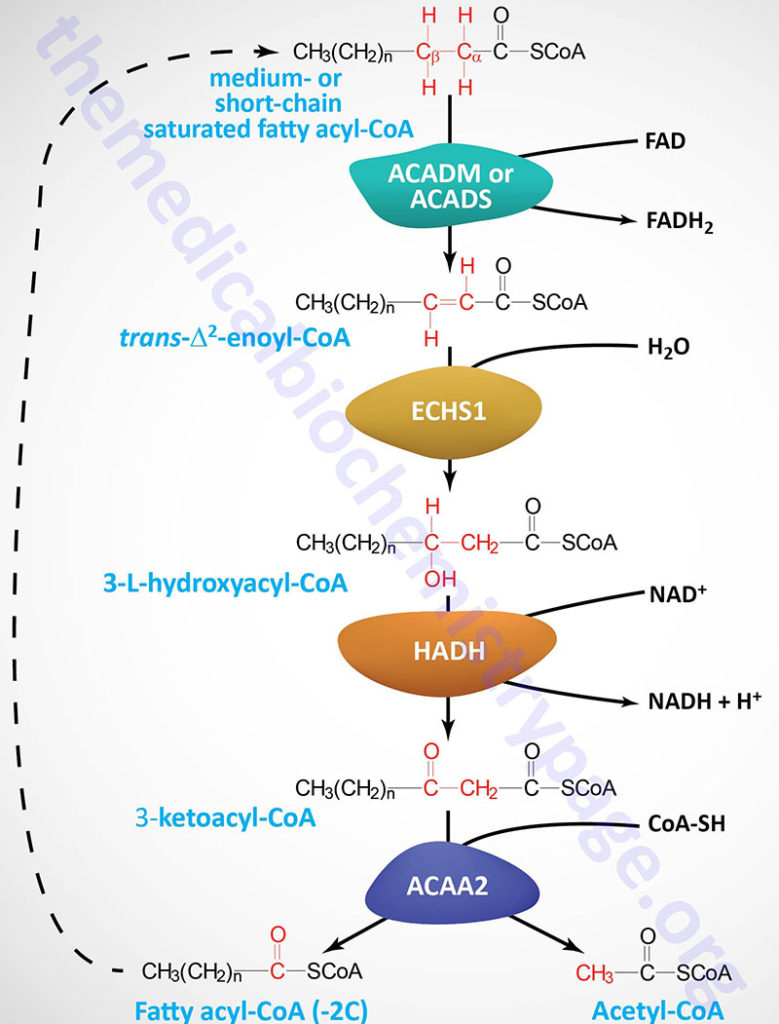

Each round of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation involves four steps that, in order, are oxidation, hydration, oxidation, and cleavage. The first oxidation step in mitochondrial β-oxidation involves a family of FAD-dependent acyl-CoA dehydrogenases that act on saturated fatty acids. Each of these dehydrogenases has a range of substrate specificities determined by the length of the fatty acid.

Each round of fatty acid β-oxidation produces one mole of FADH2, one mole of NADH, and one mole of acetyl-CoA. The acetyl-CoA, the end product of each round of β-oxidation, then enters the TCA cycle, where it is further oxidized to CO2 with the concomitant generation of three moles of NADH, one mole of FADH2 and one mole of ATP. The NADH and FADH2 generated during the fat oxidation and acetyl-CoA oxidation in the TCA cycle then can enter the respiratory pathway for the production of ATP via oxidative phosphorylation.

Short-Chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase: SCAD

Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD, also called butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase) prefers fats of 4–6 carbons in length. The SCAD enzyme (also known as ACAD3) is encoded by the ACADS (acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short chain) gene.

The ACADS gene is located on chromosome 12q24.31 and is composed of 11 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding proteins of 412 amino acids and 408 amino acids.

Medium-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogeanse: MCAD

Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD; also known as ACAD1) prefers fats of 4–16 carbons in length with maximal activity for C10 acyl-CoAs. The MCAD enzyme is encoded by the ACADM gene.

The ACADM gene is located on chromosome 1p31.1 and is composed of 13 exons generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs each encoding a unique protein isoform.

Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase

Long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD; also known as ACAD4) prefers fats of 10-18 carbons in length with maximal activity for C12 acyl-CoAs. The LCAD enzyme is encoded by the ACADL gene. The ACADL gene is located on chromosome 2q34 and is composed of 12 exons that encode a 430 amino acid precursor protein. However, due to low level expression of the ACADL gene in humans, the encoded acyl-CoA dehydrogenase plays a limited, if at all, role in mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation.

Expression of the ACADL gene in humans primarily occurs in alveolar type II pneumocytes which are the specialized cells of the alveolar epithelium that synthesize and secrete pulmonary surfactant. Pulmonary surfactant is a complex of lipid (90%) and protein (10%) where the primary lipid is dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC; also called dipalmitoyllecithin).

Very Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase

Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD; also known as ACAD6) prefers fats of 16-24 carbons and is inactive on any fatty acid less than 12 carbons. Unlike the localization of SCAD and MCAD to the mitochondrial matrix, VLCAD is an inner mitochondrial membrane-localized enzyme.

The VLCAD enzyme is encoded by the ACADVL gene. The ACADVL gene is located on chromosome 17p13.1 and is composed of 22 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs each of which encode distinct protein isoforms. The isoform 4 encoding ACADVL mRNA does not initiate translation efficiently and is, therefore, a likely mRNA candidate for nonsense mediated decay, NMD.

Additional Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Family Members

In addition to the fatty acyl-CoA dehydrogenases, SCAD, MCAD, LCAD, and VLCAD, humans express seven additional acyl-CoA dehydrogenases, not all of which are involved in lipid oxidation. These additional enzymes are isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase (also known as ACAD2; encoded by the IVD gene), glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (also known as ACAD5; encoded by the GCDH gene), short/branched-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (also known as ACAD7; encoded by the ACADSB gene), ACAD8, ACAD9, ACAD10, and ACAD11.

The IVD and ACAD8 encoded proteins are involved in the catabolism of leucine and valine, respectively. The GCDH encoded enzyme is involved in the conversion of glutaryl-CoA to crotonyl-CoA derived through the catabolism of tryptophan and the catabolism of lysine.

The ACADSB encoded enzyme prefers the branched-chain acyl-CoA, 2-methylbutryl-CoA, which is a product of the catabolism of isoleucine, but is also functional on the short straight-chain acyl-CoAs, butyryl-CoA and hexanoyl-CoA.

Although ACAD9 has dehydrogenase activity towards palmitoyl-CoA and stearoyl-CoA in vitro, the enzyme appears to be involved in the assembly of complex I of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.

The ACAD10 encoded enzyme is functional only on the CoA derivative of 2-methyl substituted pentadecanoic (C15:0) acid.

The ACAD11 encoded enzyme appears to be specific for the CoA derivative of the saturated fatty acid, behenic (C22:0) acid. The major source of behenic acid is from the drumstick tree (moringa tree: Moringa oleifera) but is also present in the oils of rapeseed and peanut. Although behenic acid is poorly absorbed in humans it has been purported to result in significant increases in serum cholesterol.

Similarities and Differences in Oxidation of Different Length Fatty Acids

Although the oxidation of long-chain saturated fatty acids occurs with a chemistry that is the same as that for the oxidation of medium-chain and short-chain saturated fatty acids, there are different sets of enzymes involved. Following the FAD-dependent acyl-CoA dehydrogenase step, the next three steps in mitochondrial β-oxidation involve a hydration step, another oxidation step, and finally a hydrolytic reaction that requires CoA and releases acetyl-CoA and a fatty acyl-CoA two carbon atoms shorter than the initial substrate.

The enzymes of long-chain fatty acid oxidation are localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane. In the oxidation of these substrates, until they become medium-chain length, the water addition is catalyzed by an enoyl-CoA hydratase activity, the second oxidation step is catalyzed by an NAD+-dependent long-chain hydroxacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity [long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) activity], and finally the cleavage into an acyl-CoA and an acetyl-CoA is catalyzed by a thiolase activity. For the oxidation of long-chain saturated fatty acids these three activities are encoded in a multifunctional enzyme called the mitochondrial trifunctional protein, MTP (also known simply as trifunctional protein: TFP).

MTP is a heterooctameric complex composed of four α-subunits encoded by the HADHA gene and four β-subunits encoded by the HADHB gene. The α-subunits contain the enoyl-CoA hydratase (also called long-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase, LCEH) and long-chain hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) activities, while the β-subunits possess the long-chain 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (LCKAT; also called β-ketothiolase or just thiolase) activity.

It is important to point out that there is a β-ketothiolase involved in isoleucine catabolism. As indicated in the Table below, this enzyme is encoded by the ACAT1 gene. The significance of this information relates to the fact that there is an inborn error in metabolism referred to as β-ketothiolase deficiency and this disorder is not related to fatty acid metabolism.

The HADHA gene is located on chromosome 2p23.3 and is composed of 20 exons that encode a 763 amino acid precursor protein.

The HADHB gene is also located on chromosome 2p23.3 in a head-to-head orientation with the HADHA gene. The HADHB gene is composed of 17 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a distinct protein isoform.

Medium-chain and short-chain saturated fatty acids are oxidized by soluble mitochondrial matrix enzymes. Following the action of MCAD and SCAD the resulting enoyl-CoAs are substrates for the enoyl-CoA hydratase encoded by the ECHS1 (enoyl-CoA hydratase, short chain 1; also identified as SCEH) gene. The ECHS1 encoded enzyme is often referred to as crotonase. The ECHS1 gene is located on chromosome 10q26.3 and is composed of 8 exons that encode a 290 amino acid protein.

The next step in medium- and short-chain fatty acid β-oxidation is catalyzed by hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (also called short-chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, SCHAD) which is encoded by the HADH gene. This dehydrogenase exhibits highest specificity for medium-chain saturated fatty acids. The HADH gene is located on chromosome 4q25 and is composed of 11 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encoded a distinct protein isoform. Mutations in the HADH gene are associated with familial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia.

The thiolase reaction is catalyzed by the ACAA2 encoded enzyme (see the Table below) which is also referred to as medium-chain 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, MCKAT.

The mammalian genome actually encodes five distinct enzymes with thiolase activity as outlined in the following Table.

Table of Mammalian Thiolase Genes

| Thiolase Gene Symbol | Comments |

| ACAA1 | acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1; also called peroxisomal 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase; involved in peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation; located on chromosome 3p22.2 spanning 11 kb composed of 12 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two isoforms of the enzyme (isoform a is 424 amino acids, isoform b is 331 amino acids) |

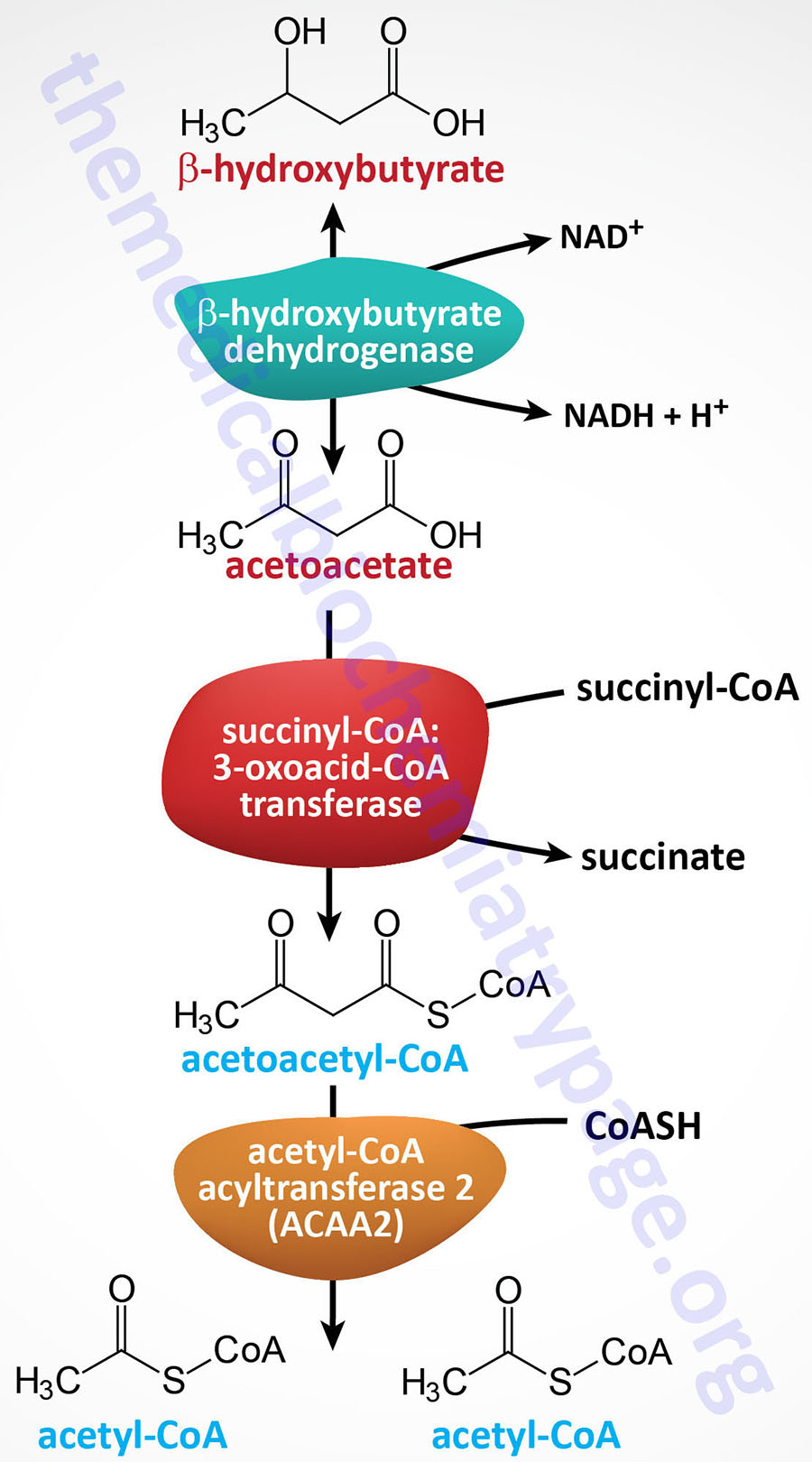

| ACAA2 | acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 2; also called mitochondrial 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase or medium-chain 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (MCKAT); catalyzes the terminal reaction of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation of medium- and short-chain fatty acids and the breakdown of the ketone, acetoacetyl-CoA, to two moles of acetyl-CoA; activity similar to that catalyzed by HADHB of the MTP; located on chromosome 18q21.1 and composed of 10 exons that encode a 397 amino acid protein |

| ACAT1 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1; also called mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase; involved in ketone body synthesis (see below) in the liver; located on chromosome 11q22.3 spanning 27 kb composed of 17 exons that generate 13 alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode five distinct protein isoforms; 9 of the 13 alternatively spliced mRNAs encode the same 337 amino acid protein (isoform e); the protein encoded by the SOAT1 gene (sterol O-acyltransferase 1) was originally referred to as acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase 1, ACAT1 but due to the nomenclature conflict is no longer designated with this acronym |

| ACAT2 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2; also called cytosolic acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase; involved in cholesterol biosynthesis and in the utilization of ketone bodies by the brain, cardiac muscle, and several other tissues; located on chromosome 6q25.3 and is composed of 10 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two isoforms of the enzyme (isoform 1 is amino 397 acids, isoform 2 is 426 amino acids); the protein encoded by the SOAT2 gene (sterol O-acyltransferase 2) was originally referred to as acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase 2, ACAT2 but due to the nomenclature conflict is no longer designated with this acronym |

| HADHB | hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase/3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase/enoyl-CoA hydratase, beta subunit; 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase; β-ketothiolase; HADHB encodes the β-subunit of mitochondrial trifunctional protein (MTP); located on chromosome 2p23.3 composed of 17 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs each of which encode a distinct protein isoform |

Pathway of Mitochondrial β-Oxidation of Long-Chain Fatty Acids

Pathway of Mitochondrial β-Oxidation of Medium- and Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Energy Yield from Mitochondrial β-Oxidation of Fatty Acids

The oxidation of fatty acids yields significantly more energy per carbon atom than does the oxidation of carbohydrates. The net result of the oxidation of one mole of oleic acid (an 18-carbon fatty acid) will be 146 moles of ATP (2 mole equivalents are used during the activation of the fatty acid), as compared with 114 moles from an equivalent number of glucose carbon atoms.

β-Oxidation of Fatty Acids with Odd Numbers of Carbon Atoms: Propionate Metabolism

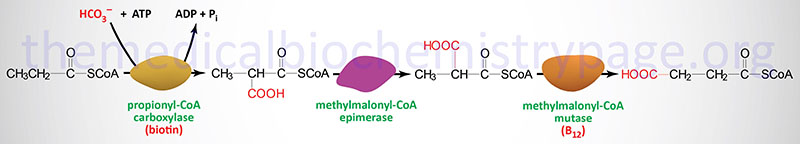

The majority of natural animal derived fatty acids contain an even number of carbon atoms. Fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms (odd-chain fatty acids, OCFA) are primarily found in the fat and milk of ruminant animals with a small proportion of plant derived fatty acids being OCFA. Upon complete β-oxidation of OCFA there results a single mole of propionyl-CoA. The propionyl-CoA is converted, via a mitochondrially-localized three reaction ATP-dependent pathway, to succinyl-CoA. The succinyl-CoA can then enter the TCA cycle for further oxidation or can be used for the synthesis of heme.

Propionyl-CoA carboxylase is called an ABC enzyme due to the requirements for ATP, Biotin, and CO2 for the reaction. The metabolic significance of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase in this pathway is that it is one of only two enzymes that requires a vitamin B12-derived co-factor for activity. The other B12-requiring enzyme is methionine synthase (see the Amino Acid Biosynthesis page). This same propionyl-CoA conversion pathway is required for the metabolism of the amino acids valine, methionine, isoleucine, and threonine. For this reason this three-step reaction pathway is often remembered by the mnemonic as the VOMIT pathway, where V stands for valine, O for odd-chain fatty acids, M for methionine, I for isoleucine, and T for threonine.

Propionyl-CoA carboxylase functions as a heterododecameric enzyme (subunit composition: α6β6) and the two different subunits are encoded by the PCCA and PCCB genes, respectively. The biotin-dependent carboxylating enzymes in mammals are multifunctional and contain three distinct enzymatic activities that may be contained in a single protein or in different subunits of the multisubunit enzymes. These three enzymatic activities are the biotin carboxylase (BC), the carboxyltransferase (CT), and the biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP) activities. The α-subunit of propionyl-CoA carboxylase contains the these activities of a typical biotin-dependent carboxylase. The BC domain of the α-subunit resides in the N-terminal region and the BCCP domain resides in the C-terminal region. Propionyl-CoA carboxylase has a domain, called the biotin transfer (BT) domain, that is not found in the other biotin-dependent carboxylase family enzymes. The BT domain is found in the middle of the α-subunit and is required for interactions between the α- and β-subunits.

The PCCA gene is located on chromosome 13q32.3 and is composed of 32 exons that generate eleven alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a unique protein isoform.

The PCCB gene is located on chromosome 3q22.3 and is composed of 17 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding precursor proteins of 539 amino acids (isoform 1) and 559 amino acids (isoform 2).

Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase is encoded by the MCEE gene located on chromosome 2p13.3 and is composed of 4 exons that encode a 176 amino acid precursor protein.

Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase is encoded by the MMUT gene located on chromosome 6p12.3 and is composed of 13 exons that encode a precursor protein of 750 amino acids. Mutations in the MMUT gene are one cause of the methylmalonic acidemias.