Last Updated: October 30, 2025

Introduction to Congenital Erythropoietic Porphyria

Congenital erythropoietic porphyria, CEP (also referred to as Günther disease) is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder. CEP a disorder that is a member of a family of disorders referred to as the porphyrias. Each disease in this family results from deficiencies in a specific enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of heme (also called the porphyrin pathway). The term porphyria is derived from the Greek term porphura which means “purple pigment” in reference to the coloration of body fluids in patients suffering from the originally described porphyria which is now known as porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT).

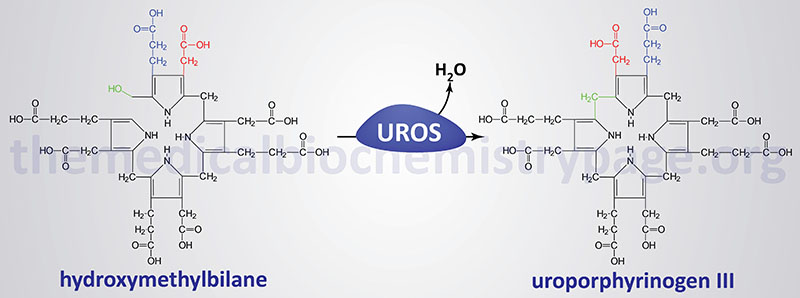

The porphyrias are classified on the basis of the tissue that is the predominant site of accumulation of metabolic intermediates. These classifications are “hepatic” or “erythroid”. Each disease is also further characterized as being acute or cutaneous dependent upon the major clinical features of the disease. CEP results from deficiencies in uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS), also called uroporphyrinogen III cosynthase or hydroxymethylbilane hydrolase (cyclizing). As the name of the disorder implies, CEP is an erythroid porphyria and it is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder.

Molecular Biology of CEP

The uroporphyrinogen III synthase gene (UROS) is located on chromosome 10q26.2 spanning 34 kb and is composed of 17 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a distinct protein isoform. The alternative splicing occurs in a tissue-specific manner such that there is an erythroid cell-specific UROS isoform and another isoform is expressed in all tissues and is referred to as the house-keeping form. The house-keeping transcript contains exon 1 and then exons 2B through 10 while the erythroid-specific transcript contains exons 2A and 2B through 10.

Several mutations have been identified in the UROS gene including missense, nonsense, and splicing mutations, large and small deletions and insertions. The most common mutation, occurring in about 35% of CEP patients, is a missense mutation leading to the substitution of arginine for cysteine at amino acid 73 (C73R).

Clinical Features of CEP

Deficiencies in UROS result in the overproduction of the non-physiological and pathogenic series I porphyrins, uroporphyrin I and coproporphyrin I via the non-enzymatic cyclization of hydroxymethylbilane. These compounds are found in plasma, red blood cells, urine, and feces and are deposited in many tissues. Excretion of these compounds causes the urine to be red and this phenotype can be evidenced in infancy. The tissue deposition of these compounds causes light-sensitization and CEP is characterized by blistering skin lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin resulting in severe damage to skin beginning in childhood. The blistering lesions of CEP rupture easily and heal slowly. The poor healing of the wounds can lead to secondary infections. Due to repeated blistering and rupture, the skin becomes thickened, scarred and calcified resembling features of scleroderma. Hypertrichosis (excessive growth of hair in locations where it is not normally found) is often severe leading to what is sometimes called the “werewolf syndrome”. These symptoms of CEP are similar to those of hepatoerythropoietic porphyria (HEP).

The clinical spectrum of CEP is highly variable and ranges from nonimmune hydrops fetalis as a result of severe hemolytic anemia in utero to late onset mild cases where the only symptoms are cutaneous lesions in the adult. The life expectancy of individuals with CEP is diminished in the severe cases due to hematologic complications and the increased risk and frequency of infections.

Treatment of CEP Patients

Treatment of CEP requires frequent transfusions for the anemia and which also reduces erythropoiesis thus, lower the level of heme synthesis. Bone marrow transplantation is curative for CEP.