Last Updated: December 29, 2025

Pathways of Ethanol Metabolism

Ethanol is a small two carbon alcohol that, due to its small size and alcoholic hydroxyl group is soluble in both aqueous and lipid environments. This allows ethanol to freely pass from bodily fluids into cells. Since the portal circulation from the small intestines passes first through the liver, the bulk of ingested alcohol is metabolized in the liver. The process of ethanol oxidation involves at least three distinct enzymatic pathways.

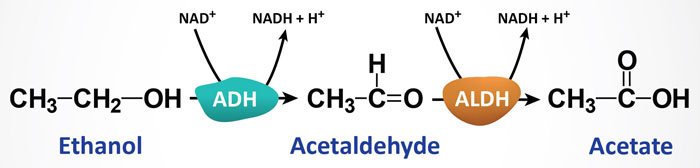

The most significant pathway, responsible for the bulk of ethanol metabolism, is that initiated by alcohol dehydrogenase, ADH. As outlined below, humans express several ADH genes with the class I members being responsible for hepatic ethanol metabolism. The ADH enzymes are NAD+-requiring and they are expressed at high concentrations in hepatocytes. Animal cells (primarily hepatocytes) contain cytosolic ADH which oxidizes ethanol to acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde then enters the mitochondria where it is oxidized to acetate by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). A cytosolic ALDH exists but is responsible for only a minor amount of acetaldehyde oxidation.

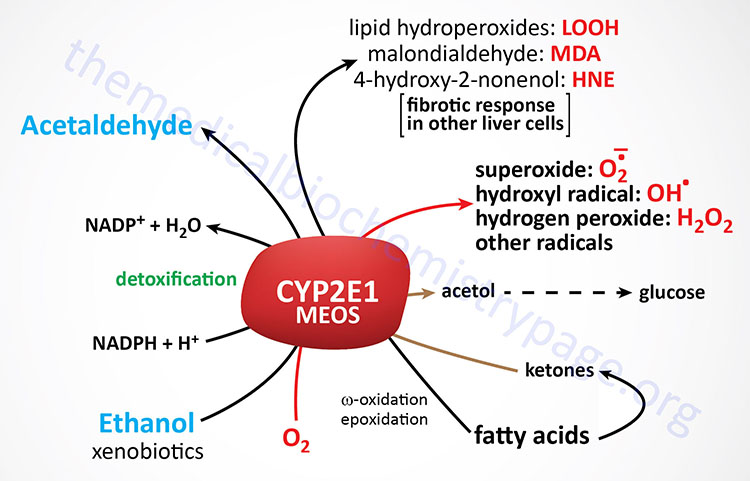

The second major pathway for ethanol metabolism is the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS) which involves the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2E1 and requires NADPH instead of NAD+ as for ADH. The MEOS pathway is induced in individuals who chronically consume alcohol.

The third pathway involves a non-oxidative pathway catalyzed by fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) synthase. This latter pathway results in the formation of fatty acid ethyl esters and takes place primarily in the liver and pancreas, both of which are highly susceptible to the toxic effects of alcohol.

Oxidation of ethanol can also occur in peroxisomes via the activity of catalase. However, this oxidation pathway requires the presence of a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) generating system and as such plays no major role in alcohol metabolism under normal physiological conditions.

Acetate from EtOH Metabolism and Fatty Liver

Under normal conditions the level of acetate in human serum is < 0.2mM. Therefore, the roles of acetate metabolism in mammals under normal physiological conditions remain to be established. Normal physiological sources of acetate include bacterial fermentation in the colon which increases significantly when consuming a high fiber diet. This intestinal acetate enters the portal circulation and is taken up by the liver where it is converted to acetyl-CoA. Intracellular generation of acetate is the consequence of the ubiquitously expressed cytosolic enzyme acetyl-CoA hydrolase. The acetate can then be salvaged by reactivation to acetyl-CoA.

In the nervous system, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) is degraded to acetate by acetylcholinesterase. In order to replenish the pool of ACh the acetate must be reactivated to acetyl-CoA so that it can participate in the choline acetyltransferase catalyzed reaction.

Acetate is also generated within the nucleus of all cells via the action of histone deacetylases (HDAC). As with the other sources of acetate, this nuclear acetate must be reactivated before it can be oxidized or reused.

Under conditions of prolonged starvation and in type 1 diabetes, the endogenous pathways of acetate production are the main sources for serum acetate. Following the consumption of ethanol, acetate levels can be elevated by as much as 20–fold.

Acetate, from whatever source, is converted to acetyl-CoA by ATP-dependent acetyl-CoA synthetases (AceCS: encoded by acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member genes: ACSS) by the following reaction:

ATP + acetate + CoA ↔ AMP + PPi + acetyl-CoA

Humans express cytosolic/nuclear and mitochondrial acetyl-CoA synthetases, encoded by the ACSS2 and ACSS1 genes, respectively. Expression of ACSS2 is under the control of SREBP-1c which is itself transcriptionally regulated by PGC-1α. Interestingly, mammalian AceCS are regulated by reversible acetylation catalyzed by the sirtuins, SIRT1 and SIRT3, and the activity of PGC-1α is also regulated by SIRT1 activity. Cytosolic AceCS (encoded by the ACSS2 gene) is a target of cytoplasmic SIRT1 whereas, mitochondrial AceCS (encoded by the ACSS1 gene) is a target of mitochondrial SIRT3.

The primary causes of fatty liver syndrome (hepatic steatosis) induced by excess alcohol consumption are the altered NADH/NAD+ levels that in turn inhibits gluconeogenesis, inhibits fatty acid oxidation, and inhibits the activity of the TCA cycle (see below for details). Each of these inhibited pathways results in the diversion of acetyl-CoA into de novo fatty acid synthesis. Ethanol has also been shown to activate SREBP-1c which results in the transcriptional activation of numerous genes involved in lipogenesis. Given that large amounts of acetate are generated via ethanol metabolism in the liver, this can be a significant contributor to the overall pool of acetyl-CoA utilized as the precursor for fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis.

Enzymes of Ethanol Metabolism

Alcohol Dehydrogenases

In humans there are multiple isoforms of ADH encoded for by eight different ADH genes. Seven of the eight ADH genes reside within a 365kbp region on chromosome 4q23. The ADHFE1 (alcohol dehydrogenase iron containing 1) gene resides on chromosome 8q13.1.

All of the ADH genes on chromosome 4q23 are members of a large family of enzymes known as the medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (MDR) superfamily. Within the human genome there are at least 25 members of the MDR family of genes.

Functional ADH exists as either a homo- or a heterodimer and the active enzymes are divided into five distinct classes denoted I–V. It should be pointed out that humans evolved to express multiple ADH genes and isoforms, not for metabolism of ethanol, but to metabolize naturally occurring alcohols found in foods as well as those produced by intestinal bacteria. As an example, one form of ADH (encoded by the ADH7 gene) is responsible for the metabolism of not only ethanol but also retinol to retinaldehyde which is the form of vitamin A necessary for vision.

Table of Mammalian Alcohol Dehydrogenases

| Gene/*Allele ID | Gene Class | Protein Name | KM(mM) for Ethanol | Primary Tissue |

| ADHFE1 | hydroxyacid-oxoacid transhydrogenase | unknown; primary substrate is gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GBH) | heart, liver, adipose tissue | |

| ADH1A | I | α; originally identified as ADH1 | 4.0 | liver |

| ADH1B*1 | I | β1; these alleles were originally identified as ADH2 | 0.05 | liver, lung |

| ADH1B*2 | I | β2 | 0.9 | |

| ADH1B*3 | I | β3 | 40 | |

| ADH1C*1 | I | γ1; originally identified as ADH3 | 1.0 | liver, stomach |

| ADH1C*2 | I | γ2 | 0.6 | |

| ADH4 | II | π (pi) | 30 | liver, cornea |

| ADH5 (also identified as ADHX) | III | χ (chi); originally identified as formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FDH) | >1,000 | widely expressed |

| ADH6 | V | ADH6 | unknown | liver, stomach |

| ADH7 | IV | σ | 30 | liver, stomach |

The hepatic forms of ADH are derived from the protein subunits encoded by the class I genes: ADH1A (also known as ADH1), ADH1B (also known as ADH2), and ADH1C (also known as ADH3). The α, β, and γ subunits encoded by these three genes, respectively, can form homo- and heterodimers as indicated above. These ADH isoforms account for the vast majority of ethanol oxidation in the liver.

As the concentration of ethanol increases in the liver the π-ADH isoform, encoded by the ADH4 gene, contributes significantly to overall hepatic ethanol oxidation.

The ADH5 gene is ubiquitously expressed and the encoded protein functions in the oxidation of long-chain primary alcohols and as a formaldehyde dehydrogenase. The ADH5 encoded protein exhibits little, if any, ethanol oxidizing activity as can be seen by the extremely high Km indicated in the Table.

The ADH6 encoded enzyme has not been characterized so little is known regarding its substrate(s) and activity.

As indicated above the ADH7 encoded enzyme oxidizes both ethanol and retinol.

As a consequence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in several of the ADH genes there are isoforms derived from the same gene that exhibit different kinetic characteristics. As shown in the Table above there are three known polymorphisms in the ADH1B gene and two in the ADH1C gene.

The ADH1B*1 allele, encoding the β1 subunit, is referred to as the reference ADH1 allele. This particular allele encodes Arg(R) at positions 48 and 370.

The ADH1B*2 allele encodes the β2 subunit that has His(H) at position 48.

The ADH1B*3 allele encodes the β3 subunit that has Cys(C) at position 370.

Both the ADH1B*2 and ADH1B*3 encoded subunits harbor amino acid substitutions that affect the binding of the NAD+ cofactor. The consequence of these alleles is that the ADH enzyme has a much higher turnover rate because the NADH is more readily released at the completion of the reaction.

The ADH1B*2 allele is common in person of Asian descent while the ADH1B*3 allele is common in people of African descent. The activity of the ADH1B*2 protein is on the order of 40 times greater than the ADH1B*1 protein. Individuals who express the ADH1B*2 allele are, therefore, much less likely (deemed protective) to abuse alcohol since they rapidly produce large quantities of acetaldehyde resulting in rapid onset of severe side effects such as tachycardia, nausea, flushing, and vomiting.

There are two known alleles in the ADH1C gene. The ADH1C*1 allele encodes the γ1 subunit which contains Arg(R) at position 272 and Ile(I) at position 350. The ADH1C*2 allele encodes the γ2 subunit that has Gln(Q) at position 272 and Val(V) at position 350. In almost all cases the dimers formed from the subunits encoded by these two ADH1C alleles are homodimeric (e.g. γ1γ1). A third ADH1C allele encodes a Thr(T) at position 352 (identified as the ADH1C*Thr352 allele) that has been found in Native American populations but the protein has yet to be fully characterized.

Aldehyde Dehydrogenases

The second reaction of ethanol metabolism is catalyzed by enzymes of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) family. Humans express 19 genes that encode enzymes of the ALDH family. There are two primary ALDH genes in humans that encode enzymes that are responsible for the oxidation of the acetaldehyde generated during the oxidation of ethanol. These genes are identified as ALDH1A1 and ALDH2 and they encode the ALDH1 and ALDH2 enzymes, respectively. The ALDH1 protein is a cytosolic enzyme while the ALDH2 proteins reside in the mitochondria. The ALDH1B1 (commonly identified as ALDHX) encoded aldehyde dehydrogenase has also been shown to contribute to mitochondrial oxidation of acetaldehyde derived from ethanol.

The ALDH1A1 gene is located on chromosome 9q21.13 and is composed of 13 exons that encode a 501 amino acid protein.

The ALDH2 gene is found on chromosome 12q24.12 and is composed of 13 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode proteins of 517 amino acids (isoform 1) and 470 amino acids (isoform 2).

Table of Human Aldehyde Dehydrogenases

| ALDH Family | Gene | Common Enzyme Name Name | Functions / Comments |

| ALDH1/2 | ALDH1A1 | retinal dehydrogenase 1 (RALDH1) | primarily localized to the cytosol; involved in the synthesis of retinoic acid from retinaldehyde; although retinal is the major substrate, cytosolic acetaldehyde is also metabolized by ALDH1A1; is also involved in the synthesis of the neurotransmitter GABA in astrocytes |

| ALDH1/2 | ALDH1A2 | retinal dehydrogenase 2 (RALDH2) | primarily localized to the cytosol; involved in the synthesis of retinoic acid from retinaldehyde; |

| ALDH1/2 | ALDH1A3 | retinal dehydrogenase 3 (RALDH3) | primarily localized to the cytosol; involved in the synthesis of retinoic acid from retinaldehyde; |

| ALDH1/2 | ALDH1L1 | cytosolic 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase; 10-FTHFDH | primarily localized to the cytosol; important enzyme in the folate cycle |

| ALDH1/2 | ALDH1L2 | mitochondrial 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase; mtFDH | primarily localized to the mitochondria; important in the processes of mitochondrial folate homeostasis |

| ALDH1/2 | ALDH1B1 | ALDH5 or ALDHX | primarily localized to the mitochondria; acetaldehyde metabolizing enzyme |

| ALDH1/2 | ALDH2 | ALDH2 | primarily localized to the mitochondria; primary acetaldehyde metabolizing enzyme |

| ALDH3 | ALDH3A1 | ALDH3 | primarily localized to the cytosol and nucleus; oxidizes toxic medium-chain aldehydes, that are derived from lipid peroxidation, to their corresponding carboxylic acids; protects cells from DNA damage and apoptosis |

| ALDH3 | ALDH3A2 | fatty ALDH (FALDH) | primarily localized to the microsomal and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes; functions in the conversion of pristanal to pristanic acid in the process of phytanic acid oxidation |

| ALDH3 | ALDH3B1 | ALDH7 | primarily localized to the cytosol; oxidizes medium- and long-chain aldehydes; expression is increased in certain cancers |

| ALDH3 | ALDH3B2 | ALDH8 | primarily localized to lipid droplets; oxidizes medium- and long-chain aldehydes; expression is increased in certain cancers |

| ALDH4 | ALDH4A1 | Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase: P5CDH | primarily localized to the mitochondria; involved in arginine, ornithine and proline catabolism where it converts Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate to glutamate |

| ALDH5 | ALDH5A1 | succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase: SSADH | primarily localized to the mitochondria; involved in the oxidation of succinic semialdehyde to succinate in the context of the GABA shunt |

| ALDH6 | ALDH6A1 | methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase: MMSDH | primarily localized to the mitochondria; involved in valine catabolism where it converts methylmalonate semialdehyde to propionyl-CoA; also important in the metabolism of β-aminoisobutyrate (BAIBA) the valine- and thymine-derived exerkine |

| ALDH7 | ALDH7A1 | α-aminoadipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (AASADH; also designated α-AASDH); also known as antiquitin 1 (ATQ1) and as betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase | primarily localized to the cytosol and nucleus; involved in the catabolism of lysine via the saccharopine pathway; also involved in the pathway of betaine synthesis from choline |

| ALDH8 | ALDH8A1 | 2-aminomuconic semialdehyde dehydrogenase; ALDH12 | primarily localized to the cytosol; involved in the catabolism of tryptophan |

| ALDH9 | ALDH9A1 | 4-trimethylaminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase; TMABA-DH | primarily localized to the cytosol; involved in the synthesis of carnitine from lysine; also involved in the conversion of γ-aminobutyraldehyde (GABAL) to the important neurotransmitter GABA; also converts 4-(trimethylamino)butyraldehyde (TMABAL) to betaine |

| ALDH16 | ALDH16A1 | ALDH16A1 | primarily localized to membranes; does not possess catalytic activity; interacts with hypoxanthine–guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT) of the purine nucleotide salvage pathway |

| ALDH18 | ALDH18A1 | Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase; P5C synthase | primarily localized to the mitochondria and intracellular membranes; is involved in the oxidation of glutamate to Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate in the context of overall arginine metabolism |

The bulk of acetaldehyde oxidation occurs in the mitochondria via ALDH2. However, some oxidation will occur in the cytosol via ALDH1 as a means to help control overall levels of acetaldehyde. This latter fact is most apparent in individuals with ALDH2 alleles that exhibit low to no acetaldehyde oxidizing capacity. Several ALDH2 polymorphisms are known to exist in various populations. Indeed, the most highly studied gene variations in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes are those in the ALDH2 gene. The ALDH2*2 allele harbors a Lys(K) residue at position 487 instead of the normal Glu(D) residue. This allele encodes a nearly inactive ALDH2 enzyme.

Of particular biochemical and physiological significance is the fact that the ALDH2*2 allele acts in a near dominant manner such that even heterozygotes have almost no detectable ALDH2 activity. The ALDH2*2 allele is prevalent in people of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean descent but is essentially absent from persons of African or European descent. This particular ALDH2 allele is responsible for the ease with which many Orientals become intoxicated by alcohol consumption and this fact is due to the reduced rate of ethanol metabolism. In addition, because the levels of acetaldehyde in the blood of these individuals rises rapidly following alcohol consumption it leads to the highly adverse reactions to this compound that includes severe flushing, nausea, and tachycardia. Due to the negative effects of the ALDH2*2 allele, even heterozygous individuals are strongly protected against alcohol dependence (discussed below).

Microsomal Ethanol Oxidation System: MEOS

The original model of alcohol metabolism in humans involved ADH as the sole physiologically significant pathway of oxidation. However, under conditions of chronic alcohol ingestion, the pathway of ethanol oxidation via solely ADH and ALDH could not account for all of the increased metabolism. Original studies in rodents demonstrated that the alcohol-induced increase in metabolism was associated with hepatic smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER; also referred to as microsomal membranes).

Although catalase is associated with peroxisomes and microsomal membranes it was clearly shown not to be responsible for the observed microsomal ethanol oxidation. This ethanol-induced metabolic system is therefore, referred to as the microsomal ethanol oxidation system (MEOS). The MEOS was shown to contain a cytochrome P450 activity responsible for ethanol oxidation and that this activity was distinct from ADH and catalase. The ethanol-induced cytochrome P450 present in the MEOS was purified and designated as CYP2E1.

The CYP2E1 gene is located on chromosome 10q26.3 and is composed of 9 exons that encode a 493 amino acid precursor protein. Expression of the CYP2E1 gene is restricted to the liver. Induction of CYP2E1 mRNA and enzyme activity ranges from 4- to 10-fold following ethanol consumption.

The cytochrome P450 activity of the MEOS is not solely due to CYP2E1 as it has been shown that in human liver microsomes CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 also contribute to ethanol oxidation in this subcellular compartment. However, it should be noted that CYP2E1-dependent ethanol oxidation activity is at least twice that of either of the other two enzymes. Therefore, CYP2E1 represents the major MEOS activity. In addition, the activity of CYP2E1 is responsible for the majority of ethanol metabolism in the brain.

Combined, the activities of CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 are comparable to that of CYP2E1, thus it is important to appreciate that these two enzymes can indeed contribute significantly to microsomal ethanol oxidation and thus, are likely to also contribute to the pathophysiology associated with hepatic ethanol oxidation.

Given that the MEOS pathway for ethanol metabolism is induced in chronic alcoholics, the enhanced ethanol metabolism likely contributes to alcoholics’ metabolic tolerance for ethanol which in turn promotes further alcohol consumption. The activity of CYP2E1 is also essential in the metabolism of several xenobiotics, particularly those found in cigarette smoke (e.g. benzene and nitrosamines). Therefore, the increased level of expression of this enzyme in alcoholics can have a significant impact on the production of toxic metabolites and this is thought to contribute to ethanol-induced liver injury (discussed below). Of particular clinical significance is that increased levels of CYP2E1 result in accelerated metabolism of several medications. CYP2E1 activity results in the conversion of the non-aspirin pain reliever, acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol), into toxic metabolites that can result in severe liver damage. Additionally, the metabolism of medications by CYP2E1 can lead to tolerance and ineffective dosages. Medications that are metabolized by CYP2E1 include the hypertension drug propranolol, the anticoagulant warfarin, and the sedative diazepam.

Metabolism of ethanol by CYP2E1 also results in a significant increase in free radical and acetaldehyde production which, in turn, diminish reduced glutathione (GSH) and other defense systems against oxidative stress leading to further hepatocyte damage. Increased activity of CYP2E1 results in accelerated production of lipid hydroperoxides (designated LOOH in the Figure above) and is a significant contributor to the development of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). MAFLD is also referred to as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, MASLD. MAFLD was formerly referred to as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD. MASH was formerly referred to as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, NASH.

Both MAFLD and MASH are commonly associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. Along with increased CYP2E1 activity there is an induction of microsomal enzymes involved in lipoprotein production, resulting in hyperlipemia which contributes to the development of MAFLD and MASH (discussed in more detail below).

The function of CYP2E1 is not solely for the metabolism of ethanol and xenobiotics. The enzyme also plays a role in normal physiological processes. CYP2E1 is involved in fatty acid oxidation as well as the diversion of ketones into the gluconeogenesis pathway. With respect to ketone utilization, CYP2E1 is responsible for metabolism of acetone which is a product of the ketogenesis pathway. CYP2E1 is involved in the conversion of acetone to acetol which is then converted to methylglyoxal, both of which can participate in gluconeogenesis. Methylglyoxal is converted to lactate via the actions of glyoxalase I (GLO1) and glyoxalase II (GLO2). With respect to fatty acid metabolism, CYP2E1 catalyzes the microsomal (ω-1)- and (ω-2)-hydroxylation of saturated fatty acids and the epoxidation of unsaturated fatty acids.

CYP2E1 and Acetaminophen Toxicity

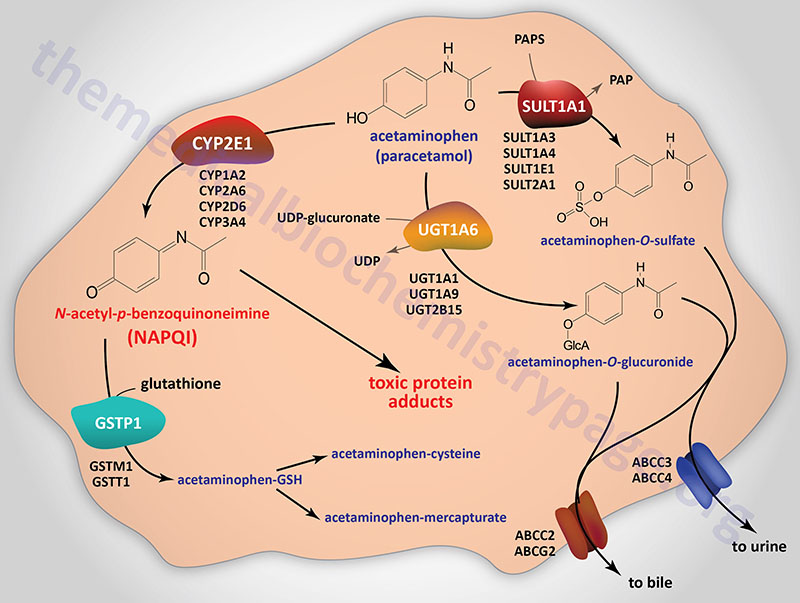

Acetaminophen [N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP), also commonly called paracetamol, is a widely used over-the-counter medication for its analgesic and antipyretic properties in many formulations in both adults and children. The maximum recommended therapeutic dose of acetaminophen/paracetamol is 4 gm/day in adults and 50–75 mg/kg/day in children. Consumption of a single dose greater than 7 gm in an adult and 150 mg/kg in a child is considered potentially toxic to the liver and kidneys. The toxicity of acetaminophen (paracetamol) is due to its metabolism to the highly active metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). Indeed, acetaminophen overdose is one of the most common drug-related toxicities.

The metabolism of acetaminophen occurs primarily in the liver and, to a lesser extent, the kidneys and intestines. Following the administration of a therapeutic dose, essentially all of the acetaminophen is converted to pharmacologically inactive glucuronide and sulfate conjugates. At normal therapeutic dosing only a minor fraction of acetaminophen is oxidized to the reactive metabolite NAPQI. The glucuronidation of acetaminophen is catalyzed by at least four different UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzymes, UGT1A1, UGT1A6, UGT1A9, and UGT2B15. The UGT1A6 and UGT1A9 enzymes are the predominant acetaminophen glucuronidating enzymes.

The sulfation of acetaminophen is catalyzed by a number of different sulfotransferase enzyme family members including SULT1A1, SULT1A3, SULT1A4, SULT1E1, and SULT2A1. The sulfotransferases use the activated form of sulfate, 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate, (PAPS) in the process of attaching sulfate to their substrate.

Following glucuronidation or sulfation the modified acetaminophen is transported out of hepatocytes into the blood or the bile canaliculi via ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family transporters. The transporters encoded by the ABCC3 and ABCC4 gene transport the modified acetaminophen into the blood while those encoded by the ABCC2 and ABCG2 gene transport the compounds into the bile.

NAPQI is highly reactive and is primarily responsible for acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Metabolism of acetaminophen to NAPQI is carried out by various CYP enzymes including CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4. Of particular significance to ethanol metabolism and acetaminophen toxicity is the role of CYP2E1 in the generation of NAPQI. Of all the CYP enzymes converting acetaminophen to NAPQI, CYP2E1 is the most significant. As indicated above, the chronic consumption of ethanol results in the induction of the CYP2E1 gene and this can result in severe toxicity to acetaminophen due to enhanced conversion to NAPQI.

The normal route for the detoxification of NAPQI is through its binding to the sulfhydryl group of glutathione (GSH). This detoxification reaction is catalyzed by at least three members of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) family of enzymes, specifically GSTM1, GSTP1, and GSTT1, where GSTP1 is the major contributor to NAPQI conjugation to GSH. Following glutathione conjugation NAPQI is ultimately excreted in the urine as cysteine and mercapturic acid conjugates.

Although most of the NAPQI is formed in the liver, the kidney also metabolizes acetaminophen to the toxic metabolite and releases the cysteine conjugate into the bile as well as the blood for further elimination in urine.

At doses of acetaminophen that exceed 4 gm/day the normal sulfation pathway becomes saturated, whereas glucuronidation and oxidation to NAPQI increase. This situation is demonstrably exacerbated in the context of ethanol consumption and the induction of CYP2E1. The glucuronidation pathway can also become saturated leading to even more acetaminophen oxidation to NAPQI, especially during ethanol consumption and metabolism.

In the context of excessive NAPQI production there is an eventual depletion of GSH stores. Under these conditions NAPQI will form adducts with proteins through the sulfhydryl side chains of cysteines. In this protein adduct pathway NAPQI primarily targets mitochondrial proteins and ion channels, leading to the loss of energy production, disturbances in ionic balance, and ultimately cell death.

In conditions of acetaminophen toxicity the administration of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been shown to replenish GSH stores, to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the mitochondria, and to enhance the metabolism of acetaminophen via the sulfation pathway. If NAC is administered within 8–10 hr after an acute overdose, there is a reduced risk for hepatotoxicity and protection from renal failure.

Ethanol Metabolism and Alcoholism

There are several different alleles of both ADH and ALDH genes, such as indicated in the Table above for the ADH1B and ADH1C genes. Several of these alleles have been correlated with either an increased or decreased propensity toward alcohol abuse or dependence. Of clinical significance is the fact that these associations between ADH and ALDH alleles and alcoholism are the strongest and most widely reproduced associations of any gene with this disorder.

Variations in the rate of alcohol absorption, distribution, and elimination contribute significantly to clinical conditions observed after chronic alcohol consumption. These variations have been attributed to both genetic and environmental factors, gender, drinking pattern, fasting or fed states, and chronic alcohol consumption.

Class I ADH and ALDH2 play a central role in alcohol metabolism. Variations in the genes encoding ADH and ALDH produce enzymes that vary in activity. This genetic variability has been associated with an individuals susceptibility to developing alcoholism and alcohol-related tissue damage. The ADH enzymes are responsible for the metabolism of various substances, including ethanol. The activity of these enzymes varies across different organs. When ethanol is present, the metabolism of the other substances that ADH acts on may be inhibited, which may contribute to ethanol-induced tissue damage.

As shown in the Table above, polymorphisms exist in the ADH1B and ADH1C genes, and the different enzymes that result from these polymorphisms are associated with varying levels of activity. The ADH1B alleles occur at different frequencies in different populations. For example, the ADH1B*1 form is found predominantly in Caucasian and Black populations, whereas ADH1B*2 frequency is higher in Chinese and Japanese populations and in 25 percent of people with Jewish ancestry. ADH1C*1 and ADH1C*2 appear with roughly equal frequency in Caucasian populations. People of Jewish descent carrying the ADH1B*2 allele show only marginally higher alcohol elimination rates compared with people with ADH1B*1. Also, African Americans, and Native Americans with the ADH1B*3 allele metabolize alcohol at a faster rate than those with ADH1B*1.

Although several ALDH isozymes have been identified, only the cytosolic ALDH1 and the mitochondrial ALDH2 metabolize acetaldehyde. There is one significant genetic polymorphism of the ALDH2 gene, resulting in allelic variants ALDH2*1 and ALDH2*2, which is virtually inactive. ALDH2*2 is present in about 50 percent of the Taiwanese, Chinese, and Japanese populations and shows virtually no acetaldehyde metabolizing activity in vitro. ALDH2*2 heterozygous, and particularly homozygotes show increased acetaldehyde levels after alcohol consumption and therefore experience significant negative physiological responses to alcohol.

Because polymorphisms of ADH and ALDH2 play an important role in determining peak blood acetaldehyde levels and voluntary ethanol consumption, they also influence vulnerability to alcohol dependence. A fast ADH or a slow ALDH are expected to elevate acetaldehyde levels and thus reduce alcohol drinking. ADH and ALDH isozyme activity also influences the prevalence of alcohol-induced tissue damage. Alcoholic cirrhosis is reduced more than 70 percent in populations carrying the ALDH2*2 allele. A positive correlation exists between genetic polymorphisms for low-activity ADH and ALDH and esophageal and head and neck cancers. Moderate drinkers who are homozygous for the slow-oxidizing ADH1C*2 allele, and therefore who are expected to drink at higher levels than those with the ADH1C*1 allele, have been shown to have a substantially decreased risk of heart attack.

Although several CYP2E1 polymorphisms have been identified, only a few studies have been done to determine the effect on alcohol metabolism and tissue damage. In one study, the presence of the rare c2 allele was associated with higher alcohol metabolism in Japanese alcoholics but this effect was only seen at high blood alcohol concentrations. Individuals with the CYP2E1 RsaI polymorphism were shown to be more likely than others to be abstain from alcohol consumption over their lifetimes.

Acute Effects of Ethanol Metabolism

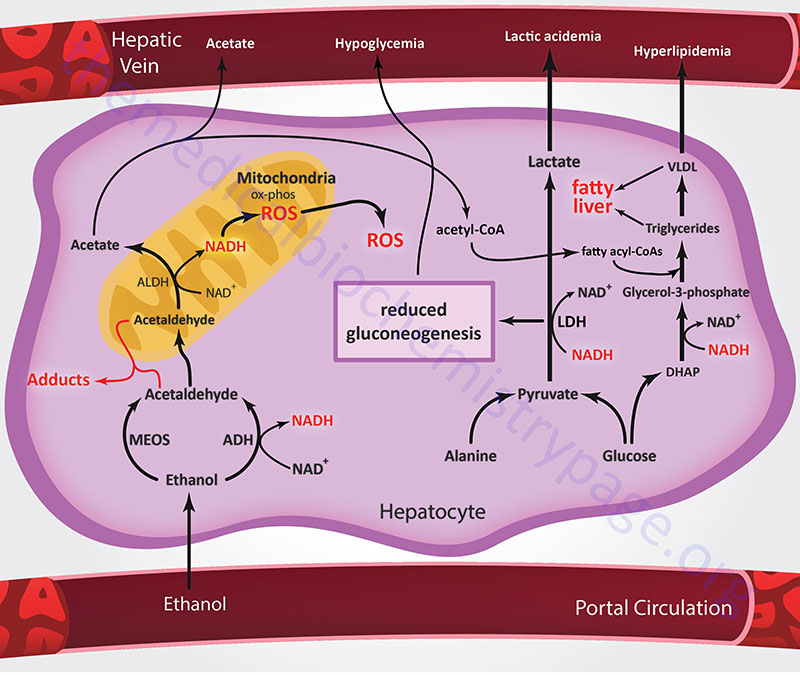

The primary acute effects of ethanol consumption are the result of the altered NADH/NAD+ ratio that is the consequence of both the ADH and ALDH catalyzed reaction. Acute effects resulting from ethanol metabolism are also due to the fact that acetaldehyde forms adducts with proteins, nucleic acids and other compounds resulting in impaired activity of the affected compounds. Additional acute consequences of ethanol metabolism include oxygen deficits (i.e., hypoxia) in the liver and the formation of highly reactive oxygen-containing molecules (i.e., reactive oxygen species, ROS) that can damage other cell components.

As indicated above, both the ADH and ALDH catalyzed oxidation reactions lead to the concomitant reduction of NAD+ to NADH. The majority of the aberrant metabolic effects of ethanol intoxication stem from the actions of ADH and ALDH and the resultant cellular imbalance in the NADH/NAD+ ratio. The NADH produced in the cytosol by ADH must be reduced back to NAD+ via either the malate-aspartate shuttle or the glycerol-phosphate shuttle. Thus, the ability of an individual to metabolize ethanol is dependent upon the capacity of hepatocytes to carry out either of these two shuttles, which in turn is affected by the rate of the TCA cycle in the mitochondria.

The rate of flux through the TCA cycle is itself being negatively affected by the NADH produced by the ADH and ALDH reactions. The reduction in NAD+ impairs the flux of glucose through glycolysis at the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase reaction, thereby limiting energy production. Additionally, there is an increased rate of hepatic lactate production due to the effect of increased NADH on direction of the hepatic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) reaction. This reversal of the LDH reaction in hepatocytes diverts pyruvate from gluconeogenesis leading to a reduction in the capacity of the liver to deliver glucose to the blood.

In addition to the effects on biochemical reactions just discussed, the NADH/NAD+ ratio, and as a consequence the redox state of the cell, is also dramatically altered as a result of ethanol metabolism. Alterations in cellular redox state are known to affect the level of expression of certain genes. To appreciate this fact one can look to research done on calorie-restriction diets. Research on reduced food intake (caloric restriction) has shown that NAD+ levels may act as a sensor that regulates the activity of certain genes. Activation of those genes, in turn, has been shown to be related to extended lifespans in a wide variety of organisms. In addition, the NAD+-regulated gene networks have been shown to reduce the incidence of age-related diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, immune deficiencies, and cardiovascular disorders. Therefore, alterations in the NADH/NAD+ ratio (in particular reductions in NAD+) resulting from ethanol metabolism may result is negatively altered expression of gene networks that promote healthy cells.

Ultimately, the NADH produced by ADH and ALDH is oxidized in the mitochondria via the pathway of oxidative phosphorylation which requires an input of oxygen. To have enough oxygen available to accept the electrons from NADH, hepatocytes must take up more oxygen than normal from the blood. Indeed, studies have shown that ethanol metabolism does result in increased uptake of oxygen by hepatocytes. Hepatocytes that reside close to the artery supplying oxygen-rich blood to the liver will tend to take up more than their normal share of oxygen. This results in limitations to the amount of oxygen left in the blood to adequately supply other liver regions. Experimental evidence shows that alcohol consumption does indeed result in significant hypoxia in perivenous hepatocytes (hepatocytes that are located close to the vein where the cleansed blood exits the liver). The perivenous hepatocytes also are the first ones to show evidence of damage from chronic alcohol consumption, indicating the potential harmful consequences of hypoxia induced by ethanol metabolism.

In addition to directly increasing oxygen consumption by hepatocytes, ethanol metabolism indirectly increases Kupffer cell oxygen use. Kupffer cells are specialized immune cells resident within the liver. When Kupffer cells become activated in response to ethanol consumption, they release various stimulatory molecules such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). The release of PGE2 results in increased metabolic activity of hepatocytes leading to even more oxygen consumption. As a result, alcohol-induced Kupffer cell activation also contributes to the onset of hypoxia.

The acetaldehyde produced by the ADH reaction, as well as the ROS produced via CYP2E1 oxidation, both can interact with proteins and other biomolecules in the cell to form both stable and unstable adducts. Acetaldehyde preferably interacts with certain amino acids in proteins but not all amino acids are equally susceptible to adduct formation with acetaldehyde. Lysine, cysteine, and aromatic amino acids are commonly altered via acetaldehyde interaction. In addition, certain proteins are particularly susceptible to forming adducts with acetaldehyde. These include proteins found in red blood cell membranes, lipoproteins, hemoglobin, albumin, collagen, tubulin, and several cytochromes including CYP2E1. Adduct formation with hemoglobin can result in reduced oxygen-binding capacity. Albumin is a major protein of the blood and among its functions is to transport fatty acids from adipose tissue. Therefore, altered albumin function could impair tissue access to energy from fatty acid oxidation. Tubulin is involved in the formation of microtubules which are necessary for intracellular transport and cell division. Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body forming a significant portion of the connective tissue.

Acetaldehyde–lysine adducts can indirectly contribute to liver damage because the body recognizes them as “foreign” resulting in an immune response and antibody production. The presence of such antibodies has been demonstrated following chronic alcohol consumption. The production of these antibodies leads to immune system-mediated destruction of hepatocytes containing these adducts. This process is known as immune-mediated hepatotoxicity or antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). Adducts formed by the interaction of acetaldehyde with erythrocyte membranes may be associated with ethanol-induced macrocytosis, a condition characterized by unusually large numbers of enlarged erythrocytes in the blood. Indeed, macrocytosis is a marker for alcohol abuse. Acetaldehyde can also form adducts with biogenic amines such as the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine. These adducts may have pharmacological effects on the nervous system.

As discussed above, ethanol metabolism by CYP2E1 and NADH oxidation by the electron transport chain generate ROS that lead to lipid peroxidation. Ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation is associated with the formation of malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), both of which can form adducts with proteins. Acetaldehyde and MDA together can react with proteins to generate a stable MDA–acetaldehyde–protein adduct (MAA). Like the acetaldehyde-amino acid adducts, peroxylipid-acetaldehyde adducts can induce immune responses resulting in antibody formation. Importantly, MAA adducts can induce inflammatory processes in stellate and endothelial cells of the liver. Thus, there is a close link between the production of MDA and HNE, and the formation of MAA adducts and subsequent development of liver disease.

The metabolism of ethanol via the CYP2E1 pathway results in increased ROS production, including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals. ROS production is associated with cancer development, atherosclerosis, diabetes, inflammation, aging, and other harmful processes. The cell regulates ROS levels via numerous defense systems involving a variety of different antioxidant compounds (e.g. glutathione, GSH). Under normal conditions, a balance between ROS production and antioxidant removal exists in cells but this balance can be disturbed. During ethanol oxidation ROS production increases dramatically due to induction of CYP2E1 and by activation of Kupffer cells in the liver. Both acute and chronic alcohol consumption can increase ROS production and lead to oxidative stress.

Chronic Effects of Ethanol Metabolism

In addition to the negative effects of the altered NADH/NAD+ ratio on hepatic gluconeogenesis, fatty acid oxidation is also reduced as this process requires NAD+ as a cofactor. Concomitant with reduced fatty acid oxidation is enhanced fatty acid synthesis and increased triglyceride production by the liver. In the mitochondria, the production of acetate from acetaldehyde leads to increased levels of acetyl-CoA. Since the increased generation of NADH also reduces the activity of the TCA cycle, the acetyl-CoA is diverted to fatty acid synthesis. The reduction in cytosolic NAD+ leads to reduced activity of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (in the glycerol 3-phosphate to DHAP direction) resulting in increased levels of glycerol 3-phosphate which is the backbone for the synthesis of the triglycerides. Both of these two events lead to fatty acid deposition in the liver leading to fatty liver syndrome and excessive levels of lipids in the blood, referred to as hyperlipidemia.

Because ethanol metabolism by ADH and ALDH occurs essentially only in the liver, any of the adverse effects described above that are associated with ethanol metabolism by these enzymes, and the associated ROS production, primarily affect that organ. In contrast, CYP2E1 is found in many tissues in addition to the liver, including the brain, heart, lungs, neutrophils, and macrophages. Accordingly, metabolic consequences of CYP2E1-mediated ethanol oxidation will affect numerous tissues. The harmful effects associated with CYP2E1-mediated ethanol metabolism are primarily related to the production of ROS, mainly superoxide and hydroxyl radicals. In the liver, the oxidative stress resulting from CYP2E1-mediated ethanol metabolism plays an important role in alcohol-related development of liver cancer.

Chronic ethanol consumption and alcohol metabolism also negatively affects several other metabolic pathways, thereby contributing to the spectrum of metabolic disorders frequently found in alcoholics. These disorders include fatty liver syndromes such as MAFLD and MASH, hyperlipidemia, lactic acidosis, ketoacidosis, and hyperuricemia. The first stage of liver damage following chronic alcohol consumption is the appearance of fatty liver, which is followed by inflammation, apoptosis, fibrosis, and finally cirrhosis.

Chronic alcohol consumption has also been shown to significantly enhance the risk of developing cancers of the esophagus and oral cavity as well as playing a major role in the development of liver cancer. As indicated above metabolism of ethanol results in increased production of acetaldehyde and ROS. Acetaldehyde adducts are known to promote cancer development. In addition, the induction of CYP2E1 results in increased ROS production and all of the associated cellular disruptions associated with these reactive substances including cancer.

Role of Fructokinase (Ketohexokinase) in Ethanol Consumption

The metabolism of fructose is initiated via the fructokinase (ketohexokinase, KHK) catalyzed reaction which generates fructose-1-phosphate. The pathway of fructose metabolism has implications with respect to ethanol consumption. It has long been known that alcohol consumption induces a preference for carbohydrate (specifically sugars) intake and that sugar intake induces a higher likelihood for alcohol consumption. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) are also more likely to have an increased preference for sugar intake, a behavior that is also evident in the children of AUD individuals.

With respect to fructose metabolism, experiments have demonstrated that the consumption of alcohol, and its metabolism in the liver, can lead to glucose diversion into fructose which is a direct contributor to hepatic lipogenesis and the development of hepatic steatosis. The conversion of glucose to fructose involves the polyol pathway where glucose is first reduced to sorbitol via the action of the aldose reductase encoded by the AKR1B1 (aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B) gene. Sorbitol can then be oxidized to fructose via the action of sorbitol dehydrogenase encoded by the SORD gene. This pathway is activated in response to ethanol uptake by the liver as a result of the hyperosmolarity of ethanol. Changes in the osmolarity of hepatocytes leads to activation of the AKR1B1 encoded aldose reductase which results in increased diversion of glucose into the pathway of fructose metabolism.

As discussed in both the Metabolism of Glyceraldehyde Contributes to Fructose-Mediated Lipogenesis and the Intestinal Fructose Contributes to Hepatic Lipogenesis sections in the Fructose Metabolism page, the metabolism of fructose enhances lipogenesis thereby contributing to the development of pathologies associated with excess lipid accumulation such as hepatic steatosis.

Most recently (2025) it has been determined that expression of the KHK gene, that encodes both KHK-A and KHK-C (often abbreviated KHK-A/C) isoforms, is associated with an enhanced preference for ethanol consumption. In knock-out mice, the loss of the KHK gene is associated with a reduced desire for ethanol intake. Mechanistically, the role of KHK in alcohol preference is most likely due to the role of fructose metabolism in the activity levels of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), the mitochondrial enzyme that metabolizes the toxic intermediate in ethanol metabolism, acetaldehyde. Fructose metabolism in the liver enhances the upregulation of ALDH which in turn results in reduced levels acetaldehyde making consumption of alcohol more tolerable. Conversely, loss of KHK activity prevents increased activity of ALDH thereby causing levels of acetaldehyde to increase. The increased levels of acetaldehyde in turn contribute to negative physiological effects that likely lead to behavioral effects that are associated with a reduced desire to consume alcohol.

Fructose-Mediated Enhancement of Ethanol Metabolism

Two aspects related to the metabolism of fructose contribute to the observation that the rate of hepatic ethanol metabolism is accelerated in the context of fructose metabolism.

The first is that the metabolism of fructose is unregulated, resulting in a dramatic depletion of hepatic ATP and a consequent increase in ADP. The reduced level of ATP will trigger an increase in the rate of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation leading to oxidation of the NADH produced during the metabolism of ethanol.

The second is related to the various fates of fructose. Fructose can be reduced to sorbitol with the concomitant oxidation of NADH to NAD+ which is catalyzed by sorbitol dehydrogenase (SORD) of the polyol pathway. In addition, the entry of fructose into the glycolytic pathway will increase the levels of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) which in the context of ethanol metabolism, will be driven to glycerol-3-phosphate via the glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase catalyzed reaction which also oxidizes NADH to NAD+.

Fructose metabolism also leads to glyceraldehyde via the aldolase B reaction. The glyceraldehyde can be oxidized to glycerol via alcohol dehydrogenase which also oxidizes NADH to NAD+ in the context of this reaction. Glycerol is then phosphorylated by glycerol kinase yielding glycerol-3-phosphate.

The contribution of fructose metabolism to the oxidation of NADH to NAD+ consequently yields a continuous pool of NAD+ for the alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase catalyzed reactions of ethanol metabolism.

Role of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase in Toxicity of Ethanol

Epoxide hydrolases convert lipid epoxides to their corresponding diols which can attenuate the function of the lipid epoxides. Humans express four epoxide hydrolase genes, identified as EPHX1-EPHX4, that encode enzymes of the α/β hydrolase fold (ABHD) enzyme family. The EPHX2 encoded enzyme is commonly called soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH). The products of sEH are the corresponding diols. The EPHX1 encoded enzyme (commonly called microsomal epoxide hydrolase, mEH) and EPHX3 encoded enzyme (also identified as ABHD9) also carry out the metabolism of PUFA-derived epoxides. The EPHX2 encoded enzyme possesses two independently functioning domains. The N-terminal domain is a phosphatase and the C-terminal domain harbors the epoxide hydrolase activity. The functional sEH enzyme is a homodimer.

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) is predominantly found in the cytosol and is highly expressed in the liver. The primary metabolic pathway in which sEH is involved is the metabolism of arachidonic acid-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EET). The EET are derived from arachidonic acid via the actions of members of the CYP family of epoxygenases. The EET are primarily anti-inflammatory and their metabolism by sEH results in the generation of molecules (dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids) that have reduced activity or can even be pro-inflammatory.

Inactivating mutations in the EPHX2 gene that encodes sEH, as well as pharmacologic inhibition of sEH, leads to the stabilization of cellular levels of EETs, as well as other epoxy fatty acids, resulting in beneficial outcomes in several conditions. For example, inactivation of sEH ameliorates diet-induced hepatic steatosis, reduces hepatic fibrosis, and attenuates diet-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.

Consumption, and hepatic metabolism, of ethanol is associated with increased levels of sEH in the liver. Evidence in animal models of alcohol-induced liver disease has shown that disruption in the function of liver sEH results in mitigation of injury, inflammation, and hepatic steatosis caused by ethanol consumption. In addition, inactivation of sEH attenuates ethanol-induced hepatic oxidative stress and ER stress. Ethanol metabolism itself induces increased oxidative and ER stress which is further exacerbated by increased levels of sEH.

Within the liver EETs are known to reduce ethanol induction of the pro-inflammatory cytokine inducing transcription factor, NF-κB. Since sEH activity results in reduced levels of EETs it is understandable how ethanol-induced increases in sEH levels contribute to a pro-inflammatory state in the liver in response to alcohol consumption.

Role of FGF21 in Counteracting Ethanol Intoxication

Induction of FGF21 expression in the liver occurs in response to numerous metabolic stresses including protein deficiency, starvation, and ethanol. Consumption and metabolism of ethanol results in the most potent increases in the production of FGF21 in the liver. The results of this increased FGF21 include central nervous system arousal and altered hepatic ethanol metabolism. Polymorphisms in the FGF21 gene, as well as in the gene (KLB) encoding the FGF receptor binding partner, β-Klotho, have been found to be associated with a propensity for alcohol consumption.

The FGF21 produced by the liver enters the blood where is can then enter the brain and exert effects via binding to its receptor complex. The effects of FGF21 in the brain include a suppression of ethanol preference and an induction of water consumption. Within the brain, specifically within the locus coeruleus (LC), FGF21 directly activates the norepinephrine producing neurons. When norepinephrine is released from LC neurons it activates both α1– and β-adrenergic receptors in subcortical regions of the brain responsible for arousal.

Experiments in mice have shown that the activation of the noradrenergic system of the LC by FGF21 reduces the intoxication effects of ethanol. In this same animal model, knocking out the FGF21 gene leads to exacerbation of the intoxicating effects of ethanol. Conversely, the administration of FGF21 to mice following ethanol administration dramatically reduces the time required for recovery from the ethanol induced effects.

The ability of FGF21 to exert its anti-intoxicant effect can be blocked by interference with the adrenergic receptor system. Administration of either prazosin, a selective α1-adrenergic receptor blocker, and propranolol, a β-adrenergic receptor blocker, results in inhibition of the effects of FGF21 on the intoxicating effects of ethanol.

Alcoholic Ketoacidosis: AKA

Alcoholic ketoacidosis (AKA) represents a pathology that is often associated with prolonged and excessive ethanol consumption. Alcoholic ketoacidosis (also referred to as alcoholic ketosis or alcoholic acidosis) manifests with nausea, intractable vomiting, and abdominal pain. These symptoms overlap with manifestations of crises in individuals who are addicted to ethanol (alcohol dependence) and as such AKA is often not diagnosed nor treated and managed properly in the hospital setting. Forensic studies have led to the suggestion that the untreated metabolic disturbance attendant with AKA may be associated with sudden death in patients with severe alcoholism.

Alcoholic ketoacidosis was originally characterized in patients who presented with nausea, severe vomiting, and abdominal pain whose history includes prolonged heavy alcohol misuse. The severe symptoms occurred following a bout of particularly excessive ethanol intake. Due to the onset of symptoms, these patients will have discontinued ethanol consumption and as such when blood work is done in the hospital setting the results will show no ethanol. In contrast to the symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), AKA patients usually present in an alert and lucid state despite the severity of the acidosis and the marked ketonemia.

In addition to the absence of blood alcohol, AKA patients will have a normal or a reduced blood glucose level, and a variably severe metabolic acidosis with an increased anion gap. The metabolic acidosis results from the accumulation of plasma lactate and the ketone bodies, β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate. Often patients with AKA are found to have extremely elevated concentrations of plasma free fatty acids, levels that are much higher than those associated with DKA. Endocrine abnormalities are also often found in AKA patients including markedly elevated levels of cortisol and growth hormone and relatively low plasma insulin levels. The symptoms of AKA normally resolve quickly if intravenous glucose and large amounts of intravenous saline are administered.

As describes earlier, the metabolism of ethanol in the cytosol and in the mitochondria results in significant elevations of NADH in both compartments. Elevated mitochondrial NADH is thought to be pivotal in the development of the ketoacidosis and lactic acidosis seen in AKA patients. The acetate produced in the mitochondria, through the action of aldehyde dehydrogenase, can be converted to acetyl-CoA via mitochondrial acetyl-CoA synthetase or the acetate can pass to the cytosol where it is converted to acetyl-CoA via cytosolic acetyl-CoA synthetase. In the cytosol, as described above, the acetyl-CoA contributes to fatty acid synthesis and fatty infiltration in hepatocytes. In the mitochondria the acetyl-CoA is diverted into the ketone synthesis pathway producing acetoacetate which, due to the elevated NADH levels, is preferentially converted to β-hydroxybutyrate.

The metabolic disturbances that result from the altered NADH/NAD+ ratio is further exacerbated in chronic alcohol consumers since they are prone to having depleted protein and carbohydrate stores due to defective dietary habits. Whereas alcohol consumption does provide a form of caloric intake, other sources are chronically reduced, resulting in starvation and depleted hepatic glycogen stores. As indicated above the elevated NADH resulting from the metabolism of ethanol results in the impairment of hepatic gluconeogenesis from lactate, alanine (and other amino acids), and glycerol. In addition, the severe vomiting that can be induced by alcohol or that result from the complications associated with excessive ethanol ingestion lead to dehydration and decreased extracellular fluid volume, resulting in hypotension triggering a sympathetic nervous system response.

Combined with the hormonal responses to hypoglycemia and starvation chronic ethanol intake leads to reduced insulin production and increased catecholamine, cortisol, glucagon, and growth hormone release. The effects of these hormonal disturbances include increased fatty acid release from adipose tissue triglycerides. The free fatty acids contribute to the hyperlipidemia resulting from increased fatty acid and VLDL synthesis by the liver as a consequence of the increased acetyl-CoA. In addition, the free fatty acids can be oxidized in the liver contributing to the potential for increased ketogenesis.

The greatest threats to patients with AKA are the marked reduction in extracellular fluid volume (resulting in shock), hypokalemia, hypoglycemia, and acidosis. The recommended intervention is to institute rapid isotonic saline infusion along with glucose, and if necessary potassium. The use of saline infusion alone, although resulting in reductions in serum lactate, actually leads to increased serum β-hydroxybutyrate and a worsening of the metabolic acidosis. In contrast, the addition of glucose results in progressively increased pH, reductions in lactate, β-hydroxybutyrate, plasma free fatty acid, growth hormone, and cortisol levels, and an increased insulin level. In addition to saline and glucose infusion, chronic alcohol abusers should receive intravenous B vitamins.

Ethanol Metabolism and the Epigenome

Chronic alcohol consumption including in the context of addiction, clinically referred to as alcohol use disorder, as well as acute alcohol consumption, are associated with numerous changes in a wide array of organ systems and not just in the liver where it is metabolized. These changes are not only metabolic but are also associated with changes in the level of gene expression.

As indicated above, the metabolic byproduct of ethanol metabolism is acetate. The resultant acetate can be transported to the blood and distributed to numerous other tissues. Within these non-hepatic tissues, just as in the liver, the acetate is converted to acetyl-CoA.

In addition, within the brain ethanol can be metabolized to acetate through the actions of the MEOS system involving CYP2E1 and also catalase. Within the brain ethanol-derived acetate has been found to directly bind to neuronal chromatin where it is converted to acetyl-CoA via chromatin-bound acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2). The resultant acetyl-CoA can then serve as a substrate for histone acetyltransferases (HAT) and the subsequent acetylation of histones. Acetylation of histones is one of the major epigenetic modifications responsible for the control of gene expression.

In addition to its role in histone acetylation the ACSS2 encoded enzyme also functions as a lactoyl-CoA synthetase. A member of the lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) family that has been shown to function as a lactyltransferase is the KAT2A encoded enzyme which was originally identified as GCN5. The activities of ACSS2 and KAT2A function in concert to lactylate histone H3 resulting in altered expression of several genes whose encoded proteins allow tumor cells to escape immune system detection.

One result of ethanol metabolism is a rapid increase in histone acetylation in neurons of the dorsal hippocampus. These acetylation changes have been shown to last for up to eight hours after ethanol consumption. The predominant sites of acetylation in the dorsal hippocampus are within histone H3.

In addition to serving as a substrate for histone acetylation, ethanol metabolism in the brain contributes to the synthesis of glutamine in astrocytes. Astrocyte glutamine is critical in the regulation of the glutamate-glutamine cycle in the brain. The ethanol-derived astrocyte glutamine can be transported into neurons for conversion to glutamate. The metabolism of glutamate to 2-oxoglutarate (a-ketoglutarate) and then to citrate in the TCA cycle can lead to acetyl-CoA production via the action of ATP-citrate lyase. This offers another pathway by which carbon atoms from ethanol can contribute to the generation of acetyl-CoA and ultimately the acetylation of histones.

Animal studies of acetate generation in the brain have shown that the expression of several thousand different genes is induced in the hippocampus. Many of proteins encoded by these genes are involved in the signal transduction processes of learning and memory. Conversely, genes involved in immune system functions were found to be downregulated by acetate. The changes in gene expression induced by ethanol metabolism in the brain are likely to be contributory to changes in behaviors that are associated with alcohol seeking behaviors and addiction.