Last Updated: December 28, 2025

Introduction to Vitamins and Minerals

The details of the synthesis and functions of the vitamins, both water and fat soluble vitamins, are the focus of this discussion. Vitamins are organic molecules that function in a wide variety of capacities within the body. The most prominent function of the vitamins is to serve as cofactors (co-enzymes) for enzymatic reactions. The distinguishing feature of the vitamins is that they generally cannot be synthesized by mammalian cells and, therefore, must be supplied in the diet. The vitamins are of two distinct types, water soluble and fat soluble.

The minerals that are considered of dietary significance are those that are necessary to support biochemical reactions by serving both functional and structural roles as well as those serving as electrolytes. The use of the term dietary mineral is considered archaic since the intent of the term “mineral” is to describe ions not actual minerals. There are both quantity elements required by the body and trace elements. The quantity elements are sodium, magnesium, phosphorous, sulfur, chlorine, potassium and calcium. The essential trace elements are manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, selenium, molybdenum, and iodine. Additional trace elements (although not considered essential) are boron, chromium, fluoride, and silicon.

Thiamine (Thiamin)

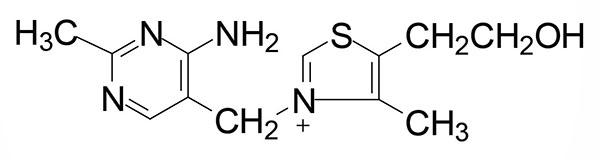

Thiamine (also written thiamin) is also known as vitamin B1. Thiamine is derived from a substituted pyrimidine and a thiazole which are coupled by a methylene bridge. Thiamine is the form of vitamin B1 that is absorbed from the small intestine.

Intestinal and Cellular Thiamine Uptake

Thiamine uptake from the intestines is a function of the solute carrier transporter family member encoded by the SLC19A2 gene. The protein encoded by the SLC19A2 gene is also known as thiamine transporter 1 (THTR1).

Uptake of thiamine into cells from the blood occurs primarily through the activity of the SLC19A3 encoded transporter. The protein encoded by the SLC19A3 gene is also known as thiamine transporter 2 (THTR2).

Mitochondrial uptake of activated thiamine (thiamine pyrophosphate: TPP) occurs via the action of the transporter encoded by the SLC25A19 gene.

Disorders of Thiamine Uptake

Mutations in the SLC19A2 gene are associated with thiamine responsive megaloblastic anemia syndrome (TRMA). TRMA is also referred to as thiamine metabolism dysfunction syndrome 1 (THMD1). TRMA is an autosomal recessive disease associated with megaloblastic anemia, diabetes mellitus, and sensorineural deafness. TRMA most often manifests between infancy and adolescence. Improvement in the anemia, and often the diabetes, is seen in patients treated with thiamine, hence the name of the disorder.

Mutations in the SLC19A3 gene are associated with thiamine metabolism dysfunction syndrome 2 (THMD2). THMD2 is also known as basal ganglia disease, biotin responsive (BBGD). THMD2 is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by episodic encephalopathy that is most often triggered by a febrile illness. This form of encephalopathy is similar to Wernicke encephalopathy that is the result of prolonged dietary deficiency of thiamine. Additional presenting symptoms include dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), confusion, seizures, and external ophthalmoplegia. The disorder can often lead to coma and death. Administration of high doses of biotin, and sometimes thiamine, has been shown to result in partial or complete improvement within days. The precise role of biotin treatment in THMD2 in unknown since the defect is in the transporter for cellular thiamine uptake. However, it is thought that biotin may lead to increased expression of SLC19A3 gene.

Mutations in the SLC25A19 gene result in microcephaly, Amish type. This disorder is associated with severe congenital microcephaly, severe 2-oxoglutaric aciduria (α-ketoglutaric aciduria), and death within the first year.

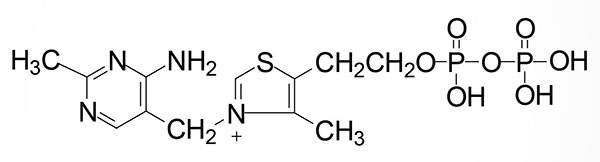

Activation of Thiamine

Thiamine is rapidly converted to its active form, thiamine pyrophosphate, TPP, by the enzyme thiamine pyrophosphokinase 1, TPK1. Although originally described as an ATP-dependent enzyme, recent work has demonstrated that TPK1 can utilize several nucleotides as phosphate donors for the phosphorylation of thiamine. These nucleotides include both purines (e.g. ATP) and pyrimidines (e.g. UTP and CTP) where the preferred phosphate donor is UTP. Indeed, the affinity of TPK1 for UTP has been shown to be on the order of 10-fold higher than for ATP.

The TPK1 gene is located on chromosome 7q35 and is composed of 26 exons that generate 15 alternatively spliced mRNAs. These TPK1 mRNAs encode a total of six different protein isoforms. Expression of the TPK1 gene is found in all tissues with highest levels in the small intestine.

Thiamine Pyrophosphate Functions

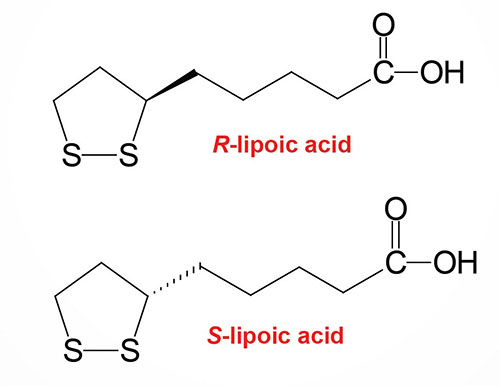

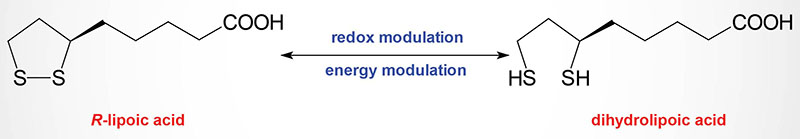

TPP is necessary as a cofactor for three critical dehydrogenases. These enzymes are the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) and 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) dehydrogenase (OGDH), both of which are associated with the TCA cycle, and branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKD) necessary for metabolism of the branched-chain amino acids, leucine, isoleucine, and valine. These three dehydrogenases also require the co-factors derived from the vitamins lipoic acid, pantothenic acid (CoA), riboflavin, and niacin. For this reason these three dehydrogenases are often referred to as the Tender (thiamine) Loving (lipoic acid) Care (CoA) For (flavin) Nancy (niacin) enzymes.

In addition to these three dehydrogenases, TPP is a required co-factor for the transketolase catalyzed reactions of the pentose phosphate pathway and it is required for the catabolism of the methyl-substituted fatty acid (phytanic acid) at the 2-hydroxyphytanoyl-CoA lyase reaction.

A deficiency in thiamine intake leads to a severely reduced capacity of cells to generate energy and to carry out reductive biosynthetic reactions as well as to synthesize nucleotides because of its role in the three critical dehydrogenase complexes.

Dietary Sources of Thiamine

The dietary requirement for thiamine is proportional to the caloric intake of the diet and ranges from 1.0–1.5 mg/day for normal adults. If the carbohydrate content of the diet is excessive then an increase in thiamine intake will be required.

The richest sources of vitamin B1 include yeasts and animal liver. Additional sources include whole-grain cereals, rye and whole-wheat flour, navy beans, kidney beans, wheat germ, as well as pork and fish.

| Food source | Thiamine content (mg) |

| Yeast, brewer’s, 2 tbls | 2.3 |

| Pork chop, lean, 100 gm | 0.9 |

| Ham, lean, 100 gm | 0.7 |

| Catfish, 100 gm cooked | 0.4 |

| Bagel, 2 oz enriched | 0.4 |

| Milk, soy, 130 gm | 0.4 |

| Beans, baked, 130 gm | 0.34 |

| Oatmeal, 130 gm cooked | 0.26 |

| Rice, white, cooked, 130 gm | 0.26 |

| Green peas, 65 gm cooked | 0.23 |

| Potato, one medium baked | 0.22 |

| Orange juice, 130 gm | 0.20 |

| Black beans, 65 gm cooked | 0.21 |

| Navy beans, 65 gm cooked | 0.19 |

| Soy nuts, 65 gm | 0.20 |

| Cashews, 65 gm | 0.15 |

| Peanuts, 65 gm | 0.10 |

Clinical Significances of Thiamine Deficiency

The earliest symptoms of thiamine deficiency include constipation, appetite suppression, and nausea. Progressive deficiency will lead to mental depression, peripheral neuropathy and fatigue. Chronic thiamine deficiency leads to more severe neurological symptoms including ataxia, mental confusion and loss of eye coordination (nystagmus). A highly diagnostic physical test of thiamine deficiency is vertical nystagmus. Vertical nystagmus is characterized by spontaneous upbeating or downbeating of the eyeball. There are numerous causes or horizontal nystagmus but vertical is only seen due to the CNS damage associated with thiamine deficiency or with phencyclidine (PCP) intoxication. Additional clinical symptoms of prolonged thiamine deficiency are related to cardiovascular and musculature defects.

Dietary thiamine deficiency is known as beriberi, is most often the result of a diet that is carbohydrate rich and thiamine deficient. An additional thiamine deficiency related syndrome is known as Wernicke syndrome which is most often associated with chronic alcohol consumption. This disease is most commonly found in chronic alcoholics due to the fact that alcohol impairs thiamine uptake from the small intestine as well as the fact that these individuals generally have poor dietetic lifestyles. Wernicke syndrome is also referred to as dry beriberi.

Prolonged dietary deficiency in thiamine leads to wet beriberi. The wet form of the disease is the result the cardiac involvement in the deficiency. At this stage in the deficiency all four chambers of the heart enlarge due to loss of energy generation and fluid retention resulting in what is called dilated cardiomyopathy. The result of the enlarged chambers is that they can’t fill completely resulting in systolic failure. Systole relates to the force associated with cardiac contraction expelling blood to arteries. Blood pumped from the left ventricle enters the aorta and is delivered to the body, whereas blood pumped from the right ventricle is sent to the lungs.

When thiamine deficiency manifests with CNS involvement it is called Korsakoff encephalopathy (or Korsakoff psychosis) and is also commonly referred to as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS). WKS is characterized by acute encephalopathy progressing to chronic impairment of short-term memory. Thiamine supplementation can reverse the symptoms of beriberi and Wernicke syndrome, however, the consequences of severe deficiency (WKS) are irreversible. The confabulation of Korsakoff psychosis is due to destruction of the mammillary bodies in the brain. The mammillary bodies are composed of two small round structures at the underside of the brain that are part of the limbic system, specifically they are part of the Papez circuit. This circuit is also called the hippocampal-mammillo-thalamo-cortical pathway. The consequence of destruction of the mammillary bodies is retrograde amnesia.

Persons afflicted with an inherited form of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome appear to have an inborn error of metabolism that is clinically important only when the diet is inadequate in thiamine. These individuals were thought to harbor an abnormality in the enzyme, transketolase. Although a variant transketolase enzyme has been proposed to be associated with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, no mutations have been found in the gene (symbol: TKT) encoding this enzyme when cloned from patients exhibiting the syndrome.

It has been speculated that the protein encoded by a transketolase-related gene (transketolase-like 1: TKTL1) may be involved in the inherited propensity for the development of WKS. Humans express a second transketolase-like gene, TKTL2. However, little is known about the potential function of the TKTL2 encoded protein.

The TKTL1 encoded protein lacks 38 amino acids, compared to the TKT protein, in the TPP-binding region. All TPP-dependent enzymes contain a highly similar TPP-binding domain and its lack in the TKTL1 protein strongly suggests that it is unlikely that TKTL1 is a TPP-dependent protein capable of catalyzing the transketolase reaction. In addition, TKTL1 lacks two vital histidine residues that are required for the catalytic processes and there is a substitution of a tryprophan at residue 124 for a serine (W124S). Also, biochemical evidence has indicated that the TKTL1 protein does not catalyze a transketolase reaction. However, computer-based modeling of both TKTL1 and TKTL2 indicates that they can form a similar binding pocket for TPP and xylulose-5 phosphate that is present in the TKT protein.

Intense interest in the TKTL1 gene, and its encoded protein, was stimulated because it was shown that the level of TKTL1 expression correlated with poor patient outcomes and metastasis in many solid tumors. In addition, specific inhibition of TKTL1 mRNA has been shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation in functional studies.

A Wernicke-like encephalopathy is associated with mutations in one of the thiamine transporter genes. As indicated above, cellular uptake of thiamine occurs via the transporter encoded by the SLC19A3 gene. Mutations in the SLC19A3 gene have been linked to an inherited Wernicke-like disorder.

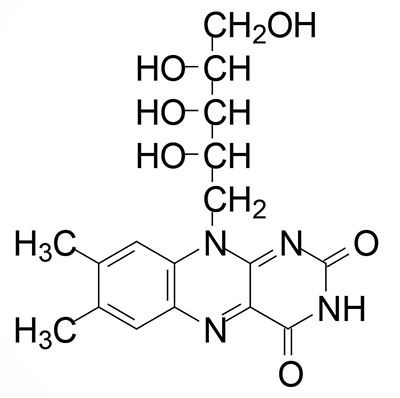

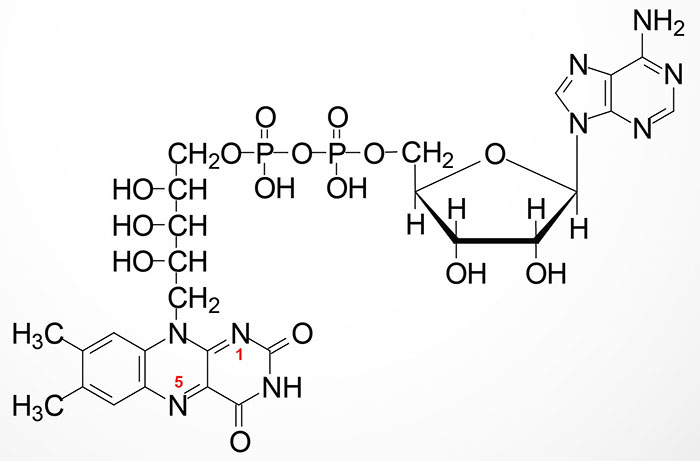

Riboflavin

Riboflavin is also known as vitamin B2. Riboflavin is the precursor for the coenzymes, flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). Dietary riboflavin is absorbed from the small intestine through the action of the solute carrier family member transporter encoded by the SLC52A3 gene. Cellular uptake of riboflavin occurs through the actions of the SLC transporters encoded by the SLC52A1 and SLC52A2 genes. The SLC52A2 gene is highly expressed in the brain and mutations in this gene result in the autosomal recessive progressive neurological disorder known as Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome 2.

FMN is synthesized from riboflavin via the ATP-dependent enzyme riboflavin kinase (RFK). RFK introduces a phosphate group onto the terminal hydroxyl of riboflavin. The RFK gene is located on chromosome 9q21.13 and is composed of 4 exons that encode a 155 amino acid protein.

FMN is then converted to FAD via the attachment of AMP (derived from ATP) though the action of flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetase 1 which is encoded by the FLAD1 gene. The FLAD1 gene is located on chromosome 1q21.3 and is composed of 7 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs each of which encode distinct isoforms of the enzyme.

The enzymes that require FMN or FAD as cofactors are termed flavoproteins. Several flavoproteins also contain metal ions and are termed metalloflavoproteins. Both classes of enzyme are involved in a wide range of red-ox reactions and includes the same critical thiamine-dependent enzymes described above, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc), 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) dehydrogenase (OGDH), and branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKD).

Additional important metabolic regulatory enzymes that require flavin as a co-factor include, succinate dehydrogenase (TCA cycle and complex II of oxidative phosphorylation), glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (involved in the glycerol phosphate shuttle and triglyceride synthesis), and xanthine oxidase involved in purine nucleotide catabolism.

During the course of the enzymatic reactions involving the flavoproteins the reduced forms of FMN and FAD are formed, FMNH2 and FADH2, respectively. The hydrogens of FADH2 are on nitrogens 1 and 5 as indicated in the Figure above.

Dietary Sources of Riboflavin

The normal daily requirement for riboflavin is 1.2–1.7 mg/day for normal adults. Riboflavin is found in dairy products, lean meats, poultry, fish, grains, broccoli, turnip greens, asparagus, spinach, and enriched food products.

| Food source | Riboflavin content (mg) |

| Beef liver, 100 gm cooked | 4.14 |

| Mackerel, 100 gm canned | 0.54 |

| Pork, loin, 85 gm cooked | 0.24 |

| Hamburger, lean, 100 gm | 0.21 |

| Chicken, dark, 85 gm cooked | 0.19 |

| Steamed clams, 100 gm | 0.43 |

| Yogurt, low-fat, 130 gm | 0.37 |

| Egg, cooked | 0.25 |

| Cheese, cottage, 65 gm | 0.21 |

| Milk, nonfat, 130 gm | 0.34 |

| Pasta, 130 gm cooked | 0.23 |

| Bagel, plain | 0.22 |

| Spinach, 65 gm cooked | 0.16 |

| Wheat germ, raw, 30 ml | 0.12 |

| Soy nuts, 65 gm | 0.65 |

| Almonds, 65 gm | 0.78 |

Clinical Significances of Flavin Deficiency

Riboflavin deficiencies are rare in the United States due to the presence of adequate amounts of the vitamin in eggs, milk, meat and cereals. Riboflavin deficiency is often seen in chronic alcoholics due to their poor dietetic habits.

Symptoms associated with riboflavin deficiency include itching and burning eyes, angular stomatitis and cheilosis (cracks and sores in the mouth and lips), bloodshot eyes, glossitis (inflammation of the tongue leading to purplish discoloration), seborrhea (dandruff, flaking skin on scalp and face), trembling, sluggishness, and photophobia (excessive light sensitivity). Riboflavin decomposes when exposed to visible light. This characteristic can lead to riboflavin deficiencies in newborns treated for hyperbilirubinemia by phototherapy requiring dietary supplementation in these infants.

Niacin

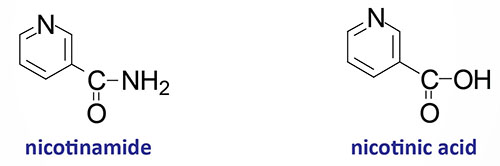

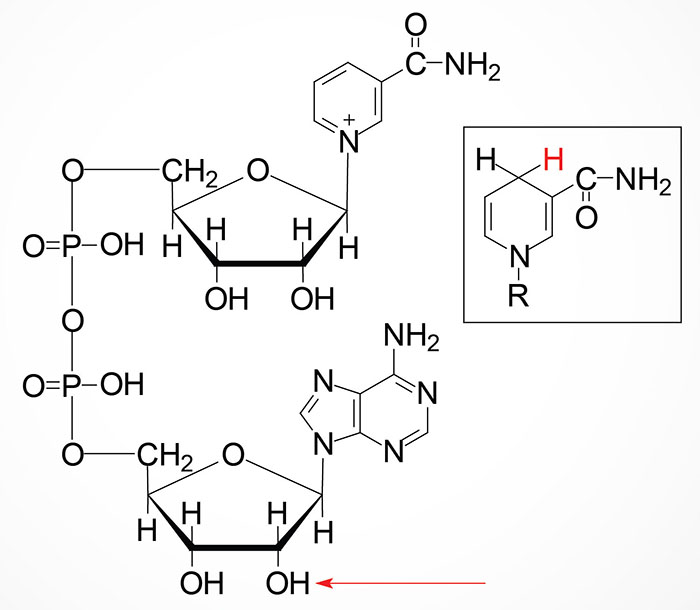

Niacin (nicotinic acid) is also known as vitamin B3. Both nicotinic acid (NA) and nicotinamide (NAM) can serve as the dietary source of the co-factor forms of vitamin B3, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+).

The details of the synthesis and salvage of NAD+ and NADP, their roles in numerous biological processes, and their degradation are covered in detail in the Vitamin B3: Metabolism and Functions page.

With respect to niacin the designation NAD (and NADP) refers to the chemical backbone of the active form of the vitamin-derived cofactor. The designations, NAD+ and NADH, as well as NADP+ and NADPH, refer to the oxidized and reduced forms of the cofactors, respectively.

Nicotinamide (NAM) can also be obtained in the diet from the consumption of NAD and NADP, both of which are hydrolyzed to nicotinamide within the lumen of the small intestines. The nicotinamide is then absorbed and delivered to the blood. Nicotinamide can also be hydrolyzed to nicotinic acid (NA) in the lumen of the small intestines and then absorbed. Intestinal uptake of nicotinic acid and nicotinamide is the function of the solute carrier family transporter encoded by the SLC22A13 gene. The SLC22A13 encoded transporter is also involved in high affinity nicotinic acid exchange in the kidneys.

Dietary Source of Niacin

Niacin is not a true vitamin in the strictest definition since NAD+ can be derived from the amino acid tryptophan. However, the ability to utilize tryptophan for NAD+ synthesis is inefficient given that approximately 60 mg of tryptophan are required to synthesize 1 mg of NAD+. Also, synthesis of NAD+ from tryptophan requires vitamins B1, B2 and B6 which would be limiting in themselves on a marginal diet.

The recommended daily requirement for niacin is 13–19 niacin equivalents (NE) per day for a normal adult. One NE is equivalent to 1 mg of free niacin. Niacin is found in liver, meat, peanuts and other nuts, and whole grains. In addition, foods that are rich in protein, with exception of tryptophan-poor grains, can satisfy some of the demand for niacin.

| Food source | Niacin content (mg) |

| Beef liver, 100 gm cooked | 14.4 |

| Chicken, white meat, cooked | 13.4 |

| Tuna, canned in water, 85 gm | 11.8 |

| Salmon, 100 gm cooked | 8.0 |

| Ground beef, 100 gm cooked | 5.3 |

| Peanuts, 65 gm | 10.5 |

| Almonds, 65 gm | 1.4 |

| Potato, baked with skin | 3.3 |

| Mushrooms, raw, 65 gm | 1.7 |

| Barley, 65 gm cooked | 1.6 |

| Corn, yellow, 65 gm | 1.3 |

| Lentils, 65 gm cooked | 1.4 |

| Sweet potatoes, 65 gm cooked | 1.2 |

| Carrot, raw, medium | 0.7 |

| Peach, raw, medium | 0.9 |

| Mango, 1 medium | 1.5 |

Clinical Significance of Niacin

A diet deficient in niacin (as well as tryptophan) leads to glossitis of the tongue (inflammation of the tongue leading to purplish discoloration), dermatitis, weight loss, diarrhea, depression and dementia. The severe symptoms, depression, dermatitis and diarrhea (referred to as the “3-D’s”), are associated with the condition known as pellagra. Several physiological conditions (e.g. Hartnup disorder and malignant carcinoid syndrome) as well as certain drug therapies (e.g. isoniazid) can lead to niacin deficiency. In Hartnup disorder, tryptophan absorption is impaired and in malignant carcinoid syndrome tryptophan metabolism is altered resulting in excess serotonin synthesis. Isoniazid (the hydrazide derivative of isonicotinic acid) was, at one time, a primary drug for chemotherapeutic treatment of tuberculosis.

Nicotinic acid (but not nicotinamide) when administered in pharmacological doses of 2–4 g/day lowers plasma cholesterol levels and has been shown to be a useful therapeutic for hypercholesterolemia. These effects of nicotinic acid are exerted by it binding to and activating the hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCA2) which was originally identified as GPR109A. The major action of nicotinic acid in this capacity is a reduction in fatty acid mobilization from adipose tissue. The HCA2 receptor activates an associated Gi-type G-protein which inhibits the production of cAMP, thereby reducing the PKA-mediated phosphorylation and activation of hormone-sensitive lipase, HSL.

Although nicotinic acid therapy lowers blood cholesterol it also causes a depletion of glycogen stores and fat reserves in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Additionally, there is an elevation in blood glucose and uric acid production. For these reasons nicotinic acid therapy is not recommended for diabetics or persons who suffer from gout. One of the side-effects of nicotinic acid therapy, that reduces patient compliance with its use, is cutaneous vasodilation resulting in a burning flush in the face and upper body. This negative effect of nicotinic acid is the result of the activation of HCA2 on macrophages.

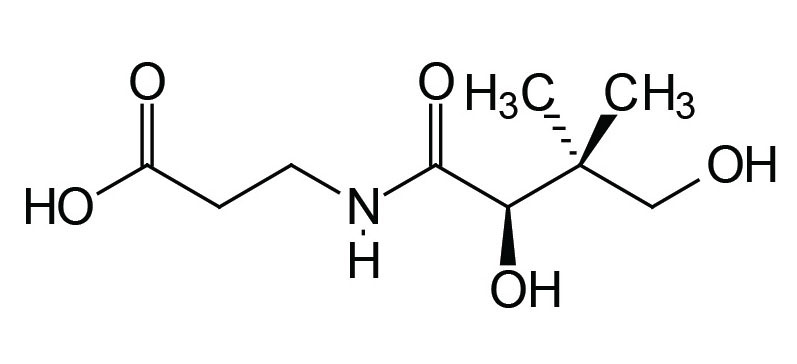

Pantothenic Acid

Pantothenic acid (pantothenate) is also known as vitamin B5. In humans pantothenic acid is synthesized by colonic bacteria from β-alanine and pantoic acid. The pantothenate is then absorbed from the intestine via the action of a Na+-dependent transporter that is also responsible for biotin absorption from the gut. This vitamin transporter is encoded by the SLC5A6 gene.

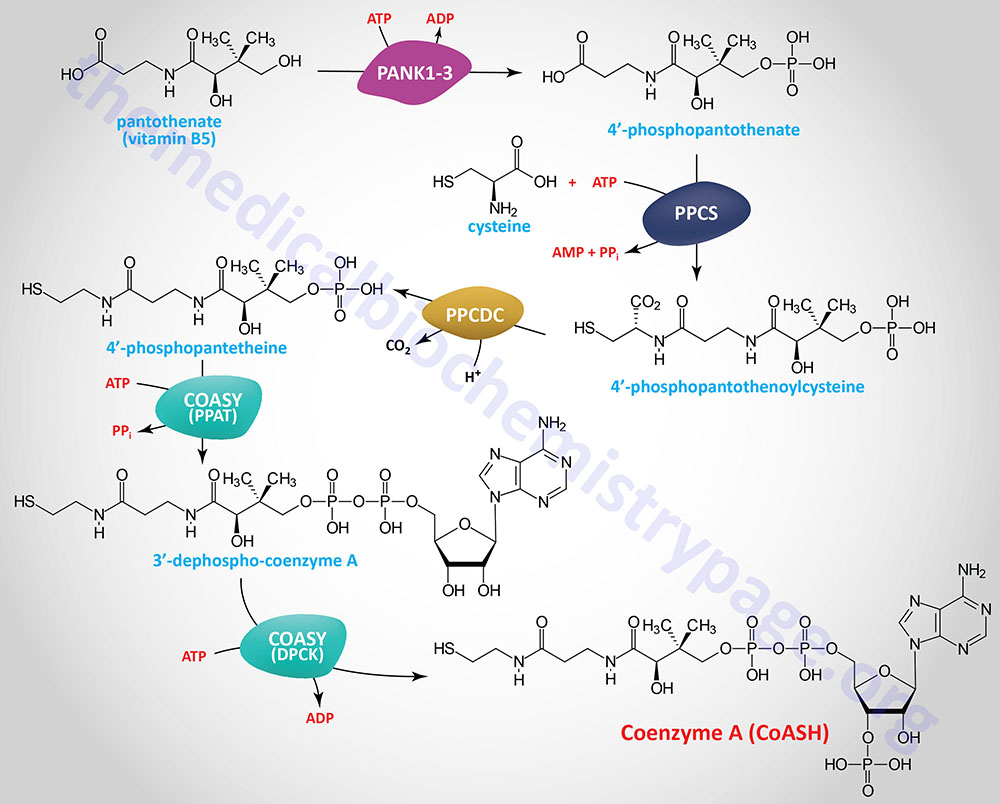

Biosynthesis of Coenzyme A (CoASH)

In the synthesis of coenzyme A (abbreviated CoA or CoASH) from pantothenate there are five reaction steps. Pantothenate is phosphorylated on the hydroxyl group via the action of the pantothenate kinases forming 4′-phosphopantethenate. Humans express four pantothenate kinase genes identified as PANK1–PANK4.

The PANK1 gene is regulated by the tumor suppressor, p53. In addition, an intronic miRNA gene resides within the PANK1 gene. The PANK1 gene is located on chromosome 10q23.31 and is composed of 11 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs each of which encode unique isoforms of the enzyme. The primary functional PANK1 enzymes are PANK1α and PANK1β. Highest levels of PANK1 expression are in the liver and kidney.

The PANK2 enzyme is the only one of the four enzymes to be localized to the mitochondria. The PANK2 gene is located on chromosome 20p13 and is composed of 10 exons that generate seven alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode five distinct protein isoforms. Transcription of one of the PNAK2 mRNAs initiates from a different start site downstream of the major transcriptional start site and translation of the encoded protein begins from a non-AUG codon.

Expression of the PANK3 gene is expressed at highest levels in the intestinal tract. The PANK3 gene is located on chromosome 5q34 and is composed of 7 exons that encode a 370 amino acid protein.

The PANK4 gene is expressed at highest levels in skeletal muscle. The PANK4 gene is located on chromosome 1p36.32 and is composed of 21 exons that encode a 781 amino acid protein. A mutation in intron 4 of the PANK4 gene is associated with autosomal dominant congenital posterior cataracts demonstrating a role for the encoded protein in the regulation of lens cell proliferation, lens epithelial cell apoptosis, lens crystallin formation, and fiber cell functions. Unlike the kinase functions of the PNAK1-3 enzymes the PANK4 enzyme functions to dephosphorylate 4′-phosphopantetheine to pantetheine.

The reactive sulfhydryl group is added to the carboxylic acid end of 4′-phosphopantothenate from cysteine via the action of phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthetase which is encoded by the PPCS gene. The PPCS gene is located on chromosome 1p34.2 and is composed of 5 exons that generate eight alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode four distinct isoforms of the enzyme. The product of the PPCS reaction is 4′-phospho-N-pantothenoylcysteine (PPC).

PPC is then decarboxylated to 4′-phosphopantetheine via the action of phosphopantothenoylcysteine decarboxylase (PPCDC). The PPCDC gene is located on chromosome 15q24.2 and is composed of 7 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding five distinct protein isoforms.

4′-Phosphopantetheine is then converted to coenzyme A via the action of the bifunctional enzyme, coenzyme A synthase encoded by the COASY gene. The phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT) domain of COASY utilizes ATP to catalyze the conversion of 4′-phosphopantetheine into dephospho-coenzyme A. The dephospho-CoA kinase (DPCK) domain of COASY catalyzes the final step in CoA synthesis by adding the phosphate from ATP to the 2′-hydroxyl of the ribose from the adenine added in the previous reaction.

The COASY gene is located on chromosome 17q21.2 and is composed of 9 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, two of which encode the same enzyme isoform.

In addition to its role in the synthesis of coenzyme A, pantothenic acid serves as a component of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain of fatty acid synthase, FAS. Pantothenate is, therefore, required for the metabolism of carbohydrate via the TCA cycle and all fats and proteins. At least 70 enzymes have been identified as requiring CoA or ACP derivatives for their function including the same critical thiamine-dependent enzymes described above, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc), 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) dehydrogenase complex (OGDH), and branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex (BCKD).

Coenzyme A Metabolism

Coenzyme A can undergo both intracellular and extracellular degradation and subsequent salvage.

Intracellular degradation and salvage of CoA begins with an acyl-CoA molecule. Enzymes of the acyl-CoA thioesterase (ACOT) family, that are responsible for the deactivation of fatty acyl-CoAs, release the CoA and the esterified fatty acid. Enzymes of the nudix hydrolase (NUDT) family, specifically NUDT7, NUDT8, and NUDT19, can hydrolyze CoA to 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate (PAP) and 4′-phosphopantetheine. The term nudix is derived from nucleoside diphosphate-linked moiety X. The same NUDT family member enzymes hydrolyze an acyl-CoA molecule releasing PAP and an acyl-4′-phosphopantetheine. The acyl group is released via the action of ACOT family enzymes generating 4′-phosphopantetheine. The 4′-phosphopantetheine can then serve as a substrate for renewed CoA synthesis via the actions of the COASY enzyme.

Extracellular turnover of free coenzyme A can proceed via dephosphorylation to 3′-dephospho-CoA or via hydrolysis yielding 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate (PAP) and 4′-phosphopantetheine. The dephosphorylation is catalyzed by extracellular alkaline phosphatase. The release of PAP and 4′-phosphopantetheine is catalyzed by extracellular enzymes of the ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (ENPP) family. The ENPP family enzymes are also likely involved in the release of AMP and 4′-phosphopantetheine from phosphopantetheine. Whether or not extracellular 4′-phosphopantetheine is a substrate for re-synthesis of CoA is unclear. However, alkaline phosphatase can remove the phosphate from 4′-phosphopantetheine to generate pantetheine. The action of enzymes of the vanin (vascular noninflammatory molecule-1) family (vanin-1, vanin-2, or vanin-3) catalyze the release of pantothenic acid and cysteamine from pantetheine. The pantothenic acid can then be transported back into cells via the SLC5A6 transporter and reused for the synthesis of CoA.

Although not involved in CoA metabolism, the biotinidase enzyme, which is involved in the release of biotin from protein to which the vitamin is covalently bound, is also a member of the vanin family of enzymes.

Functions of Coenzyme A

Coenzyme A serves numerous critical functions that include the processes of catabolism and anabolism as well as metabolic signaling. Coenzyme A exists in cells as free CoA, meaning it is unesterified or unacylated, or as esterified/acylated CoA. The two most abundant forms of acylated CoA are acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA.

The major subcellular organelles that require CoA for metabolic processes are the mitochondria and the peroxisomes. The use of CoA in metabolic signaling relates to the roles of various acylated CoA molecules, such as acetyl-CoA, crotonyl-CoA, that serve to acylate lysine residues in the nuclear histone proteins, such as is the case for nuclear acetyl-CoA, succinyl-CoA, butyryl-CoA, and propionyl-CoA. Identical types of protein lysine acylation also occur in numerous cytosolic proteins.

The transport of CoA across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the matrix is primarily carried out by two members of the SLC family of transporters, SLC25A16 and SLC25A42. Within the mitochondria CoA is an acceptor of carbons from the oxidation of carbohydrates (principally pyruvate derived via glycolysis), amino acids, fatty acids, and ketone bodies. The formation of acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA in the matrix of the mitochondria is crucial to the operation of the TCA cycle.

Within the context pf peroxisomal metabolism, CoA is required for the oxidation of very long-chain fatty acids as well as branched-chain fatty acids and the 3-methyl branched-chain fatty acid, phytanic acid.

In addition to the numerous roles of CoA in catabolic processes, it is critical for numerous anabolic processes. These processes include fatty acid synthesis, cholesterol biosynthesis, bile acid synthesis, steroid hormone biosynthesis, neurotransmitter synthesis, synthesis of heme, and the synthesis of many types of carbohydrate containing glycans that includes the glycolipids and glycoproteins. Within the overall context of lipid synthesis, these processes occur in the cytosol, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the mitochondria, and the peroxisomes. The processes of synthesis of the various lipid classes represent the most significant CoA-dependent reactions in the cell.

In the context of cytosolic and mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis, not only is CoA required, but so too is the intermediate in CoA synthesis, 4′-phosphopantetheine. The 4′-phosphopantetheine group serves as the acyl carrier portion (ACP) of several lipid biosynthetic enzymes that includes cytosolic fatty acid synthase and the mitochondrial NDUFAB1 encoded protein (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit AB1) which serves as the ACP in mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis.

The 4′-phosphopantetheine group also functions in the context of the folate cycle via the cytosolic ALDH1L1 (aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1) encoded enzyme and the functionally related mitochondrial ALDH1L2. Two additional enzymes are modified by 4′-phosphopantetheine attachment, the cytosolic AASDH (aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase) encoded enzyme and the mitochondria-localized DHRS2 encoded enzyme. The AASDH encoded enzyme is also sometimes identified as ACSF4 (acyl-CoA synthetase family member 4) and as β-alanine activating enzyme. The DHRS2 encoded enzyme is a member of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family of oxidoreductases.

The attachment of the 4′-phosphopantetheine, from CoA, to the proteins indicated, occurs on a conserved Ser residue via a phosphodiester linkage. This reaction is catalyzed by L-aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase-phosphopantetheinyltransferase which is encoded by the AASDHPPT gene. During the course of the attachment, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate (PAP) is released.

Dietary Sources of Pantothenic Acid

| Food source | Vitamin B5 content (mg) |

| Beef liver, 100 gm | 5.3 |

| Poultry, dark meat, 100 gm | 1.3 |

| Poultry, white meat, 100 gm | 1.0 |

| Salmon, 100 gm cooked | 1.4 |

| Low fat yogurt, 130 gm, | 1.5 |

| Milk, nonfat, 130 gm | 0.8 |

| Bleu cheese, 28 gm | 0.49 |

| Cottage cheese, 65 gm | 0.27 |

| Corn, cooked, 65 gm | 0.72 |

| Potato, baked, one | 0.7 |

| Sweet potato, 65 gm | 0.68 |

| Broccoli, boiled, 65 gm | 0.4 |

| Wheat germ, raw, 32 gm | 1.2 |

| Mushrooms, cooked, 65 gm | 0.84 |

| Peanuts, 65 gm | 0.9 |

| Avocado half | 1.0 |

| Sunflower seeds, 32 gm | 2.3 |

| Dates, 10 | 0.65 |

| Papaya, 65 gm | 0.33 |

| Strawberries, 130 gm | 0.25 |

| Orange juice, 235 ml | 0.24 |

Deficiency of pantothenic acid is extremely rare due to its widespread distribution in whole grain cereals, legumes and meat. Symptoms specific to pantothenate deficiency are difficult to assess since they are subtle and resemble those of other B vitamin deficiencies. These symptoms include painful and burning feet, skin abnormalities, retarded growth, dizzy spells, digestive disturbances, vomiting, restlessness, stomach stress, and muscle cramps.

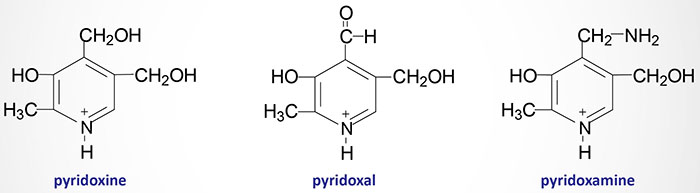

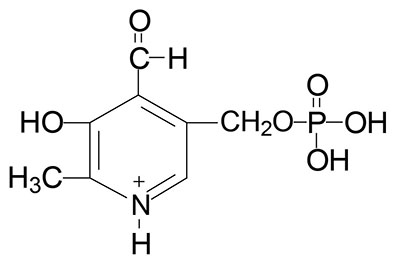

Vitamin B6

Pyridoxal, pyridoxamine and pyridoxine are collectively known as vitamin B6. All three compounds are efficiently converted to the biologically active form of vitamin B6, pyridoxal phosphate (PLP). This conversion is catalyzed by the ATP requiring enzyme, pyridoxal kinase. Pyridoxal kinase requires zinc for full activity thus making it a metalloenzyme.

Pyridoxal kinase is encoded by the PDXK gene which is located on chromosome 21q22.3 and is composed of 19 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding isoform 1 (312 amino acids) and isoform 2 (272 amino acids).

Any PLP consumed in the diet is acted upon by intestinal alkaline phosphatases that remove the phosphate. All three forms of vitamin B6 are then passively absorbed by intestinal enterocytes of the jejunum. Within intestinal enterocytes the three forms are re-phosphorylated to PLP and then delivered to the blood.

Vitamin B6 Requiring Reactions

Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) functions as a cofactor in all of the enzymes that carry out the transamination (aminotransferase) reactions required for the synthesis and catabolism of the amino acids.

PLP is a cofactor for the synthesis of several neurotransmitters including serotonin, the catecholamines dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine [critical enzyme is aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) which is encoded by the DDC gene and is more commonly referred to as DOPA decarboxylase], and γ-aminobutyric acid, GABA (critical enzyme is glutamic acid decarboxylase, GAD).

PLP is required for the synthesis of heme via the enzyme catalyzing the initial and regulated step in this pathway, δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS).

PLP is a cofactor for two enzymes involved in methionine and cysteine metabolism, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionase (cystathionine γ-lyase).

As indicated above, PLP is also required for the conversion of tryptophan to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+). PLP is also required for glycogen homeostasis as a cofactor for glycogen phosphorylase. This latter reaction is the only PLP-dependent process that is not associated with metabolism of nitrogen containing compounds (principally amino acids).

Dietary Sources of Vitamin B6

The requirement for vitamin B6 in the diet is proportional to the level of protein consumption ranging from 1.4–2.0 mg/day for a normal adult. During pregnancy and lactation the requirement for vitamin B6 increases approximately 0.6 mg/day.

| Food source | Vitamin B6 content (mg) |

| Beef liver, 100 gm | 1.4 |

| Turkey, light meat, 100 gm | 0.5 |

| Chicken, light meat, 100 gm | 0.63 |

| Salmon, 100 gm cooked | 0.65 |

| Halibut, baked, 100 gm | 0.4 |

| Potatoes, 130 gm | 0.48 |

| Sweet potatoes, 65 gm | 0.3 |

| Oatmeal, 130 gm cooked | 0.74 |

| Rice, brown, cooked, 130 gm | 0.28 |

| Brussels sprouts, 65 gm | 0.23 |

| Lentils, 65 gm cooked | 0.18 |

| Carrots, 65 gm cooked | 0.18 |

| Peanuts, 65 gm | 0.18 |

| Sunflower seeds, 32 gm | 0.26 |

| Avocado, 1 Haas | 0.48 |

| Mango | 0.28 |

| Watermelon, 130 gm | 0.22 |

| Cantaloupe, 130 gm | 0.18 |

| Prunes, 10 dried | 0.22 |

| Blackstrap molasses, 30 ml | 0.29 |

Vitamin B6 Deficiency and Disease

Deficiencies of vitamin B6 are rare and usually are related to an overall deficiency of all the B-complex vitamins. Like the role of chronic alcohol consumption and an associated poor diet leading to thiamine deficiency, alcoholism is the leading cause of deficiency in B6.

Isoniazid (see niacin deficiencies above) and penicillamine (used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and cystinurias) are two drugs that complex with pyridoxal and PLP resulting in a deficiency in this vitamin.

Deficiencies in pyridoxal kinase result in reduced synthesis of PLP and are associated with seizure disorders related to a reduction in the synthesis of GABA.

Due to its role in heme biosynthesis, deficiency in vitamin B6 can result in microcytic hypochromic anemias that are similar to those caused by iron deficiency or as a result of heavy metal (e.g. lead) poisoning.

Two additional critical enzymes requiring PLP are cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (cystathionase) which are involved in the metabolism of methionine to cysteine. Due to the role of B6 in this latter reaction, deficiencies in the vitamin can lead to homocysteinemia/uria due to a resultant blockade in the CBS reaction (see the Amino Acid Biosynthesis page for discussion of this effect).

Other symptoms that may appear with deficiency in vitamin B6 include nervousness, insomnia, skin eruptions, loss of muscular control, anemia, mouth disorders, muscular weakness, dermatitis, arm and leg cramps, loss of hair, slow learning, and water retention.

Differential Diagnosis: Several Causes of Microcytic Anemia

| Deficiency/Defect | Characteristics |

| B6 deficiency | PLP is required for the rate-limiting enzyme in heme biosynthesis: δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS); deficiency results in loss of protoporphyrin IX synthesis, therefore, there will be a significant reduction in measurable ALAS product (δ-aminolevulinic acid, δ-ALA) and protoporphyrin in these patients; loss of heme production leads to hypochromic microcytic anemia; lack of protoporphyrin results in iron deposits on mitochondria in bone marrow erythroblasts resulting in the formation of ringed sideroblasts; loss of iron incorporation into protoporphyrin IX leads to increased serum and intracellular iron concentration; increase in intracellular iron results in increased translation of ferritin as a means to prevent iron toxicity |

| Iron deficiency | iron deficiency is the leading cause of microcytic anemia; loss of iron results in reduced production of heme, thus, the result is a hypochromic microcytic anemia; lack of heme production results in loss of feed-back inhibition of ALAS, therefore these patients will have an associated increase in measurable protoporphyrin; loss of iron intake means reduced iron in the serum and reduced intracellular iron, the latter resulting in reduced ferritin translation; loss of iron for incorporation into protoporphyrin IX results in spontaneous, non-enzymatic incorporation of Zn2+ forming Zn-protoporphyrin (ZPP), ZPP causes erythrocytes to fluoresce under ultraviolet illumination and is the basis of the ZPP test for iron deficiency or lead poisoning |

| Heavy metal poisoning | heavy metals, such as lead, inhibit several enzymes of heme biosynthesis and metabolism with the most significant toxic effects resulting from inhibition of ferrochelatase, the enzyme that incorporates iron into protoporphyrin IX generating heme; similar to B6 deficiency, lead poisoning leads to increased intracellular iron in bone marrow erythroblasts causing the formation of ringed sideroblasts; because there is no heme, the ALAS reaction is not inhibited, as in the case of iron deficiency, this results in increased production of δ-ALA and protoporphyrin; lack of iron incorporation into protoporphyrin results in increased serum and intracellular iron concentrations, with the latter leading to increased ferritin synthesis as in the case of iron-deficient anemia; loss of iron for incorporation into protoporphyrin IX results in spontaneous, non-enzymatic incorporation of Zn2+ forming ZPP; as in the case of iron-deficient anemia, the ZPP test is diagnostic for lead/heavy metal poisoning |

Biotin

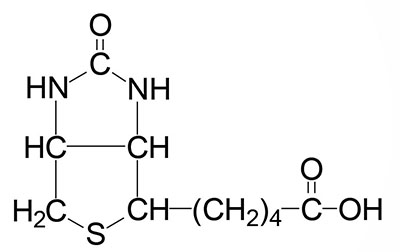

Biotin is the cofactor required of enzymes that are involved in carboxylation, decarboxylation, or transcarboxylation reactions in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Biotin is sometimes referred to as vitamin B7 or as vitamin H. Biotin, produced by intestinal bacteria, as well as that found in the diet, is bound to lysine residues in protein forming a complex that is called biocytin.

Removal of biotin from biocytin and recycling of biotin from human biotin-dependent enzymes requires the activity of the enzyme biotinidase. Biotinidase is encoded by the BTD gene.

The BTD gene is located on chromosome 3p25.1 and is composed of 10 exons that generate 41 alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode nine distinct protein isoforms. Biotinidase isoforms 1 (523 amino acids) and 5 (159 amino acids) are the most common of the proteins derived from the 41 alternative mRNAs. The clinical significance of defects in the BTD gene are described below.

When released from protein, or consumed in free form, biotin is absorbed from the lumen of the intestines through the action of the Na+-dependent vitamin transporter encoded by the SLC5A6 gene. This is the same transporter involved in pantothenate (vitamin B5) absorption.

In humans, the biotin-requiring enzymes include acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC: humans express two distinct ACC genes), pyruvate carboxylase (PC), propionyl-CoA carboxylase (PCC), and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (3MCC). The critically important biotin-requiring enzymes are ACC, PC, and PCC. All four of these enzymes are referred to as ABC enzymes because they require/utilize ATP, Biotin, and CO2.

The biotin-dependent carboxylating enzymes in mammals are multifunctional and contain three distinct enzymatic activities that may be contained in a single protein or in different subunits of the multisubunit enzymes. These three enzymatic activities are the biotin carboxylase (BC), the carboxyltransferase (CT), and the biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP) activities.

Incorporation of Biotin into Biotin-Requiring Enzymes

Incorporation of biotin into the biotin-requiring enzymes involves the activity of holocarboxylase synthetase (also known as protein-biotin ligase) that is encoded by the HLCS gene. The HLCS gene is located on chromosome 21q22.13 and is composed of 19 exons that generate eight alternatively spliced mRNAs, seven of which encode the same 726 amino acid protein.

The reaction of biotin incorporation into the biotin-requiring enzymes occurs in a two-step process that requires ATP. In the first step holocarboxylase synthetase generates a biotin-AMP intermediate and in the second step the activated biotin is transferred to the carboxylase enzyme with release of AMP.

The removal of biotin from lysine residues in proteins in the diet and from the carboxylases in cells, through the action of biotinidase, and then the incorporation of the biotin into the carboxylases, through the action of holocarboxylase synthetase, is referred to as the biotin cycle.

Biotin-Requiring Enzymes

Acetyl-CoA Carboxylases

The ACC enzymes are cytosolic enzymes with the ACC1 gene encoded protein catalyzing the rate-limiting step of fatty acid synthesis. PC is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the critical first reaction in the pathway of gluconeogenesis. PCC is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes reactions involved in the metabolism of several amino acids (valine, methionine, isoleucine, and threonine) as well as the oxidation of fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms. The role of PCC in the metabolism of these compounds is often referred to as the VOMIT pathway (Valine, Odd-chain fats, Methionine, Isoleucine, Threonine) for memorization purposes. 3MCC is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the fourth step in the catabolism of leucine.

As discussed in detail in the Synthesis of Fatty Acids page, humans express two forms of ACC (ACC1 and ACC2) both of which are multifunctional enzymes possessing all three biotin-dependent carboxylating activities.

Pyruvate Carboxylase

Pyruvate carboxylase is the critical first enzyme in the conversion of pyruvate to glucose in the pathway of gluconeogenesis. Pyruvate carboxylase (PC) is also a multifunctional enzyme containing all three activities in a single polypeptide that form an α4 homotetrameric enzyme. The human PC gene is located on chromosome 11q13.2 and contains 31 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs. These mRNAs differ in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) but all three encode the same precursor protein of 1178 amino acids. The highest levels of PC expression are in adipose tissue.

Propionyl-CoA Carboxylase

Propionyl-CoA carboxylase converts the propionyl-CoA derived from the oxidation of valine, methionine, isoleucine, and threonine, as well as fatty acids with odd numbers of carbon acids, into methylmalonyl-CoA. Propionyl-CoA carboxylase functions as a heterododecameric enzyme (subunit composition: α6β6) and the two different subunits are encoded by the PCCA and PCCB genes, respectively. The α-subunit of propionyl-CoA carboxylase contains the three activities of a typical biotin-dependent carboxylase. The BC domain of the α-subunit resides in the N-terminal region and the BCCP domain resides in the C-terminal region. Propionyl-CoA carboxylase has a domain, called the biotin transfer (BT) domain, that is not found in the other biotin-dependent carboxylase family enzymes. The BT domain is found in the middle of the α-subunit and is required for interactions between the α- and β-subunits.

The PCCA gene is located on chromosome 13q32.3 and is composed of 32 exons that generate eleven alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a unique protein isoform.

The PCCB gene is located on chromosome 3q22.3 and is composed of 17 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding precursor proteins of 539 amino acids (isoform 1) and 559 amino acids (isoform 2).

3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase

The function of 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase is to catalyze the carboxylation of 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA to 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA during the catabolism of leucine. The 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA is the product of isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase (IVD) which catalyzes the prior reaction in leucine catabolism. 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (3MCC), like PCC, is also a heterododecameric enzyme (subunit composition: α6β6). Similar to the activities of PCC, the α-subunit possesses the BC and BCCP activities and the β-subunit possesses the CT activity. The α-subunit of 3MCC is encoded by the MCCC1 gene and the β-subunit is encoded by the MCCC2 gene.

The MCCC1 gene is located on chromosome 3q27.1 and is composed of 23 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, two of which are known to encode functional protein. MCCC1 isoform 1 is a precursor protein of 725 amino acids and isoform 2 is a precursor protein of 608 amino acids. Mutations in the MCC1 gene are the cause of 3-methylcrotonylglycinuria type I.

The MCCC2 gene is located on chromosome 5q13.2 and is composed of 19 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode precursor proteins of 563 and 525 amino acids. Mutations in the MCC2 gene are the cause of 3-methylcrotonylglycinuria type II.

Dietary Sources of Biotin

Biotin is found in numerous foods and also is synthesized by intestinal bacteria. Some of the richest sources of biotin are swiss chard, tomatoes, romaine lettuce, and carrots. Additional sources include onions, cabbage, cucumber, cauliflower, mushrooms, peanuts, almonds, walnuts, oat meal, bananas, raspberries, strawberries, soy, egg yolk, and cow and goat milk.

Clinical Significance of Biotin

Given that biotin is synthesized by intestinal bacteria deficiencies of the vitamin are rare. Deficiencies are generally seen only after long antibiotic therapies which deplete the intestinal microbiota or following excessive consumption of raw eggs. The latter is due to the affinity of the egg white protein, avidin, for biotin preventing intestinal absorption of the biotin. An important autosomal recessive inherited disorder that leads to biotin deficiency is biotinidase (BTD) deficiency.

Biotinidase Deficiency

Profound biotinidase deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder that is characterized by mutations in the BTD gene that result in enzyme activity that is less than 10% of the normal. Partial biotinidase deficiency is characterized by enzyme activity that is 10%–30% of normal.

Profound biotinidase deficiency occurs with a frequency of 1 in 60,000 live births. Indeed, the frequency is high enough, and the resultant symptoms severe enough, that current neonatal disease testing includes analysis for defects in the activity of this enzyme. The most severe symptoms associated with biotin deficiency and profound biotinidase gene defects are the result of the accumulation of toxic metabolic intermediates. The symptoms of profound biotinidase deficiency include delayed development, seizures, hypotonia, respiratory difficulties, hearing and vision loss, ataxia, skin rashes, and alopecia. Patients with profound biotinidase deficiency are also highly susceptible the fungal infection, candidiasis.

Symptoms associated with partial biotinidase deficiency can be similar to those of the profound deficiency form but often these symptoms do not appear as severe except during infections, illnesses, or stress.

Holocarboxylase Synthetase Deficiency

Deficiency in holocarboxylase synthetase is an autosomal recessive disorder that results in multiple carboxylase deficiency. At least 35 different mutations in the HLCS gene have been found associated with holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency. The typical presentation of holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency is seen in the neonatal period with onset occurring within hours to weeks of birth. The classic symptoms of holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency are hypotonia, lethargy, seizures, metabolic acidosis, vomiting, hyperammonemia, developmental delay, skin rash, and alopecia.

Standard newborn screening tests include detection of holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency by analysis of blood for the presence of elevated O-(3-hydroxyvaleryl)-L-carnitine. Urine organic acid analysis in holocarboxylase synthetase deficient patients will show elevated levels of lactate, 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid, 3-hydroxypropionic acid, 3-methylcrotonic acid, methylcitric acid, and tiglylglycine. Tigylglycine is an N-acylglycine formed from glycine with an amine hydrogen substituted by a 2-methylbut-2-enoyl (tiglyl) group.

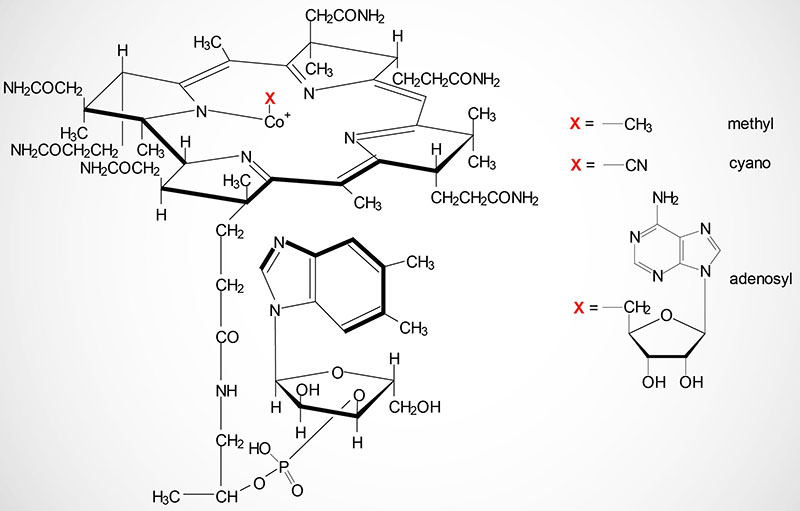

Cobalamin: Vitamin B12

Cobalamin is more commonly known as vitamin B12. Vitamin B12 is composed of a complex tetrapyrrol ring structure (corrin ring) and a cobalt ion in the center. The cobalt in cobalamin can exist in three oxidation states identified as +1 [cob(I)alamin], +2 [cob(II)alamin], and +3 [cob(III)alamin]. The most common states of the cobalt, in the context of the role of cobalamin in enzyme catalyzed reactions, are cob(I)alamin and cob(II)alamin.

Vitamin B12 is synthesized exclusively by microorganisms and is primarily found in the liver of animals bound to protein as methycobalamin or 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin. Bioavailable vitamin B12 is also present in cows milk and soybeans. The vitamin must be released from these binding proteins in order to be active and this release occurs in the stomach by the gastric protease, pepsin.

After being released by pepsin in the stomach, cobalamin is bound to an endogenous protein called haptocorrin (also known as transcobalamin I) which is encoded by the TCN1 gene. The TCN1 gene is located on chromosome 11q12.1 and is composed of 9 exons that encode a precursor protein of 433 amino acids. Expression of the TCN1 gene highest in the salivary glands. Expression levels in the gallbladder, stomach, and bone marrow are next highest but are 2-3 times lower than that of the salivary glands.

Haptocorrin is a glycoprotein that is produced by oral salivary glands in response to intake of food. The binding of hatocorrin to the cobalamin that is released by the action of pepsin, protects the vitamin while it transits through the stomach into the duodenum. Within the small intestine pancreatic trypsin hydrolyzes the haptocorrin-cobalamin complexes allowing binding of cobalamin to another protein called intrinsic factor, IF. Intrinsic factor is also called gastric intrinsic factor (GIF). Intrinsic factor is a heavily glycosylated protein that is homologous to haptocorrin. Intrinsic factor binds cobalamin only within the alkaline pH of the intestines. Haptocorrin and intrinsic factor are two of the three vitamin B12-binding proteins produced in humans.

The third vitamin B12-binding protein is transcobalamin II which is a plasma globulin that is the primary transport protein for vitamin B12 in the blood. Transcobalamin II (often called simply transcobalamin, TC) is encoded by the TCN2 gene. The TCN2 gene is located on chromosome 22q12.2 and is composed of 9 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding precursor proteins of 427 amino acids (isoform 1) and 400 amino acids (isoform 2).

Intrinsic factor is a 50-kDa glycoprotein produced by the parietal cells of the stomach. Intrinsic factor is encoded by the CBLIF (cobalamin binding intrinsic factor) gene which is also referred to as gastric intrinsic factor (GIF). The CBLIF gene is located on chromosome 11q12.1 and is composed of 9 exons that encode a 417 amino acid precursor protein. Expression of the CBLIF gene is exclusive to parietal cells of the stomach. The secretion of intrinsic factor is stimulated by all three of the mechanisms that lead to gastric acid secretion: histamine, acetylcholine, and gastrin.

Cobalamin, bound to intrinsic factor, can then bind to a receptor complex called cubilin present on the apical membranes of enterocytes in the distal ileum as well as on renal epithelial cells of the nephron in the kidney. The cubilin protein is encoded by the CUBN gene which is located on chromosome 10p13 and is composed of 71 exons that encode a 3623 amino acid precursor protein. Expression of the CUBN gene is highest in the kidney and the small intestine.

Interactions of the intrinsic factor-cobalamin complexes with cubilin requires Ca2+ ions. The cubilin protein is a peripheral membrane protein that lacks both transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Internalization of the cubilin bound intrinsic factor-cobalamin complex requires that cubilin be colocalized (anchored) with another transmembrane protein. Two proteins have been shown to fulfill the role of cubilin anchoring proteins. One of these proteins was originally identified in the mutant mouse called amnionless. The human protein is called amnion-associated transmembrane protein and it is encoded by the AMN gene. The other cubilin anchoring protein is a member of the LDL receptor-related protein (LRP) family, specifically LRP2. The AMN protein is required for intestinal uptake of cubilin-intrinsic factor-cobalamin complexes, whereas LRP2 appears to have some role in the uptake of these complexes from the nephron. However, because the disease known as Donnai-Barrow syndrome, which results from inherited mutations in the LRP2 gene, is not associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, the interactions between cubilin and LRP2 is not required for overall vitamin B12 homeostasis. It is suggested that an additional cubilin anchoring protein may yet be identified.

Upon intrinsic factor-cobalamin binding to cubilin, the complex is endocytosed. The intrinsic factor in the endocytosed complexes is degraded by lysosomal hydrolases and the cobalamin is released.

Within intestinal enterocytes cobalamin is bound to transcobalamin II (identified as TC-Cbl) for transfer from the apical (luminal) side to the basolateral (blood) side of the cell. Free cobalamin is released from the intestinal enterocytes to the blood via TC-Cbl interaction with a basolateral membrane transporter that is a member of the ATP-binding cassette family of transporters, specifically the ABCC1 transporter.

Within the blood, free cobalamin binds again to transcobalamin II. The transcobalamin II-cobalamin (TCN2-cobalamin) complexes are taken up, from the blood, by all cells via a plasma membrane transcobalamin receptor (TCBLR) encoded by the CD320 gene. The TCN2-cobalamin-TCBLR complex is internalized via endocytosis. Within the lysosome transcobalamin II is degraded and the free cobalamin is released so that it can be used as an enzyme co-factor within the cell.

The release of free cobalamin from the lysosome requires the action of the lysosomal membrane protein identified as LMBRD1 (LMBR1 domain containing 1, where LMBR1 refers to the protein identified as limb region 1 protein homolog).

Free within the cytoplasm of the cell cobalamin binds to the protein encoded by the MMACHC gene [methylmalonic aciduria (cobalamin deficiency) cblC type, with homocystinuria]. The MMACHC encoded protein dealkylates both adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl) and methylcobalamin (MeCbl) and also decyanates cyanocobalamin (CN-Cbl).

Within the cytosol cobalamin is converted to MeCbl within the context of the methionine synthase reaction. Cobalamin is also transported into the mitochondria via the action of the protein encoded by the MMAA gene [methylmalonic aciduria (cobalamin deficiency) cblA type]. Within the mitochondrion cobalamin is converted to AdoCbl which is the co-enzyme form of vitamin B12 required by methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. Conversion of cobalamin to AdoCbl is catalyzed by the protein encoded by the MMAB gene [methylmalonic aciduria (cobalamin deficiency) cblB type]. The MMAB encoded protein synthesizes AdoCbl from cobalamin [the cob(I)yrinic acid a,c-diamide form] in an ATP-dependent reaction. Deficiencies in all of the genes responsible for overall metabolism of cobalamin are associated with various forms of methylmalonic acidemia.

There are only two clinically significant reactions in the body that require vitamin B12 as a co-factor. During the catabolism of fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms and the amino acids valine, isoleucine, methionine, and threonine, the resultant propionyl-CoA is converted to succinyl-CoA for oxidation in the TCA cycle. The catabolism of these compounds into propionyl-CoA is often remembered by the mnemonic VOMIT pathway, where V is for valine, O is for odd number carbon atom fats, M is for methionine, I is for isoleucine, and T is for threonine.

The last enzyme in this pathway, methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, requires vitamin B12 as a cofactor in the conversion of methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA which then enters the TCA cycle. The 5′-deoxyadenosine derivative of cobalamin (adenosylcobalamin: AdoCbl) is required for this reaction. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase is a mitochondrial enzyme and the synthesis of the required AdoCbl occurs within the mitochondria and is catalyzed by the MMAB encoded protein as described earlier.

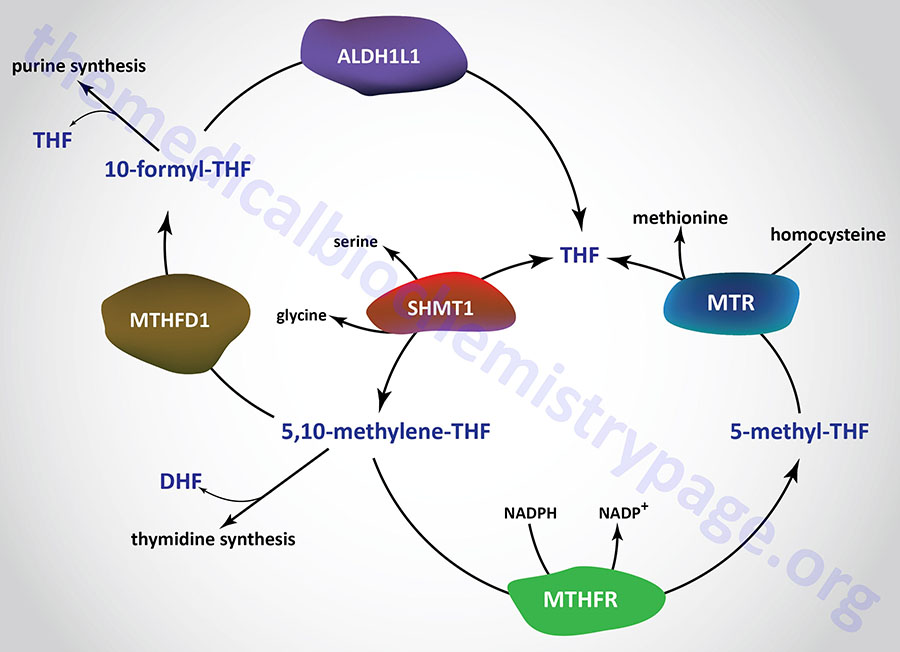

The second reaction requiring vitamin B12 catalyzes the conversion of homocysteine to methionine and is catalyzed by methionine synthase (also known as homocysteine methyltransferase). This reaction results in the transfer of the methyl group from N5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-methylTHF) to cobalamin generating tetrahydrofolate (THF) and methylcobalamin (MeCbl) during the overall reaction process.

Dietary Source of Vitamin B12

The recommended daily intake (RDA) of vitamin B12 for adults is 2.4 micrograms (μg). Vitamin B12 is found primarily in animal products. Due to the lack of sufficient vitamin B12 in plant foods it is added to breakfast cereals and this serves as a good source of the vitamin for vegetarians. Two plant sources that are useful for obtaining vitamin B12 are alfalfa and comfrey (also written comfry). However, to ensure adequate intake vegans should use a vitamin B12 supplement that contains at least 5–10μg due to the low absorption rate of the vitamin in supplement form.

| Food source | Vitamin B12 content (mcg: μg) |

| Beef liver, 100 gm | 48 |

| Rainbow trout, wild, 85 gm | 5.4 |

| Salmon, 85 gm | 4.9 |

| Beef, 85 gm | 2.4 |

| Tuna, white, 85 gm | 1.0 |

| Yogurt, plain, 130 gm | 1.4 |

| Fortified cereal, 100% RDA | 6.0 |

| Milk, 235 ml | 0.9 |

| Swiss cheese, 30 gm | 0.9 |

| Egg, 1 whole | 0.6 |

Clinical Significance of B12 Deficiency

The liver can store up 3-5 years worth of vitamin B12, hence deficiencies in this vitamin are rare. Pernicious anemia is a specific form of megaloblastic anemia resulting from vitamin B12 deficiency that develops as a result of a lack of intrinsic factor being released from stomach parietal cells leading to subsequent malabsorption of the vitamin. The major cause of the loss of intrinsic factor is an autoimmune destruction of the parietal cells that secrete it. Surgical removal of a part of the stomach can also result in loss of intrinsic factor resulting in pernicious anemia. In rare cases individuals inherit a mutation in the GIF gene that encodes intrinsic factor resulting in pernicious anemia.

The pernicious anemias result from impaired DNA synthesis due to a block in purine and thymidine biosynthesis. The block in nucleotide biosynthesis is a consequence of the effect of vitamin B12 on folate metabolism. When vitamin B12 is deficient essentially all of the folate becomes trapped as the N5-methylTHF (5-methylTHF; or simply methylTHF) derivative as a result of the loss of functional methionine synthase. This trapping prevents the synthesis of other THF derivatives required for the purine and thymidine nucleotide biosynthesis pathways.

Neurological complications also are associated with vitamin B12 deficiency and result from a progressive demyelination of nerve cells. The demyelination is thought to result from the increase in methylmalonyl-CoA that results from vitamin B12 deficiency that is associated with loss of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase activity. The loss of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase activity with deficiencies in B12 results in an accompanying methylmalonic acidemia. Methylmalonyl-CoA is a competitive inhibitor of malonyl-CoA in fatty acid biosynthesis as well as being able to substitute for malonyl-CoA in any fatty acid biosynthesis that may occur. Since the myelin sheath that protects nerve cells is in continual flux the methylmalonyl-CoA-induced inhibition of fatty acid synthesis results in the eventual destruction of the sheath. The incorporation methylmalonyl-CoA into fatty acid biosynthesis results in branched-chain fatty acids being produced that may severely alter the architecture of the normal membrane structure of nerve cells.

Contributing to the neural degeneration seen in vitamin B12 deficiency is the reduced synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM; also abbreviated AdoMet) due to loss of the methionine synthase catalyzed reaction. The conversion of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to phosphatidylcholine (PC) requires the enzyme phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (encoded by the PEMT gene) which carries out three successive SAM-dependent methylation reactions. This reaction is a critically important reaction of membrane lipid homeostasis. Therefore, the reduced capacity to carry out the methionine synthase reaction, due to nutritional or disease mediated deficiency of vitamin B12, results in reduced SAM production and as a consequence contributes to the neural degeneration (i.e. depression, peripheral neuropathy) seen in chronic B12 deficiency.

Deficiencies in B12 can also lead to elevations in the level of circulating homocysteine and elevated excretion of the oxidized dimer of homocysteine called homocystine. Elevated levels of homocysteine are known to lead to cardiovascular dysfunction. Due to its high reactivity to proteins, homocysteine is almost always bound to proteins, thus thiolating them leading to their degradation. Homocysteine also binds to albumin and hemoglobin in the blood. Some of the detrimental effects of homocysteine are due to its’ binding to lysyl oxidase, an enzyme responsible for proper maturation of the extracellular matrix proteins collagen and elastin. Production of defective collagen and elastin has a negative impact on arteries, bone, and skin and the effects on arteries are believed to be the underlying cause for cardiac dysfunction associated with elevated serum homocysteine. In individuals with homocysteine levels above ≈12μM there is an increased risk of thrombosis and cardiovascular disease. The increased risk for thrombotic episodes, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), associated with homocysteinemia is due to homocysteine serving as a contact activation nucleus for activation of the intrinsic coagulation cascade.

Folic Acid

Folic acid is sometimes referred to as vitamin B9. The terms folic acid and folate are sometimes used interchangeably but from a dietary perspective they are distinctly different. The term folate should be used to refer only to the bioactive forms of folic acid, namely dihydrofolate (DHF) and tetrahydrofolate (THF) and their derivatives.

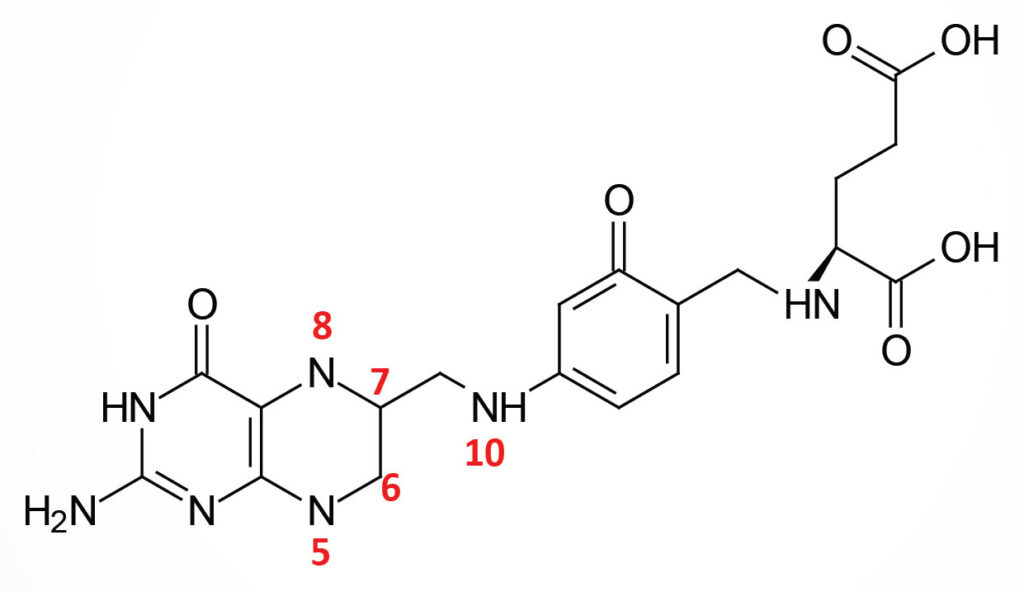

Structure of Folic Acid

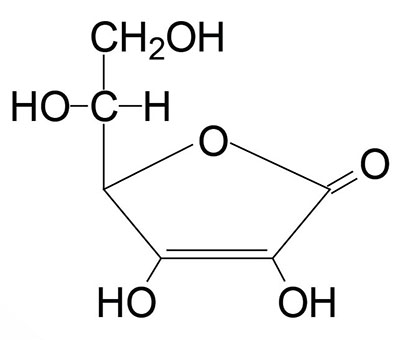

Folic acid is a conjugated molecule consisting of a pteridine ring structure linked to para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) that forms pteroic acid. Pteroic acid is then converted to folic acid through the N-esterification of glutamic acid to the carboxylic acid of the PABA portion of pteroic acid. This latter structure is the form of “folate” present in dietary supplements and when used to fortify manufactured food products.

Dietary Folate and Intestinal Uptake

Dietary folates (which are predominately the N5-methyl-THF form; 5-methyl-THF) are obtained primarily from yeasts and leafy vegetables as well as animal liver. Humans cannot synthesize PABA nor attach glutamate residues to pteroic acid, thus, requiring folic acid or folate (DHF or THF) intake in the diet.

When ingested from natural sources, or when stored in cells (predominantly in the liver and the kidneys), folates exists in a polyglutamate form. Jejunal (small intestine) mucosal cells remove the glutamate residues to the monoglutamate state through the action of the enzyme, folate hydrolase 1. Folate hydrolase 1 is also commonly called glutamate carboxypeptidase II as well as folylpoly-γ-glutamate carboxypeptidase.

Folate hydrolase 1 is encoded by the FOLH1 gene. The FOLH1 gene is located on chromosome 11p11.12 and is composed of 22 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a distinct protein isoform.

Within the intestinal enterocytes, the monoglutamate forms of the folates are less negatively charged (compared to the polyglutamic acids), and are therefore, more capable of being transported across the basolateral membrane (facing the blood) of the jejunal enterocytes and into the bloodstream.

Another enzyme, with similar activity to that of folate hydrolase 1, is called γ-glutamyl hydrolase (also known as conjugase or folate conjugase). Gamm-glutamyl hydrolase is encoded by the GGH gene. The GGH gene is located on chromosome 8q12.3 and is composed of 10 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding precursor proteins of 318 amino acids (isoform 1) and 271 amino acids (isoform 2).

The function of the GGH encoded enzyme is to remove polyglutamates from intracellular stores of the folate derivatives that, as indicated, are predominantly stored in the liver and the kidneys. The GGH encoded enzyme is localized to the lysosomes. Release of glutamates from stored folates allows for the monoglutamate forms to be excreted into the blood to meet systemic needs.

Folates in the diet are predominantly the N5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-methyl-THF or simply methylTHF) form. Dietary folates are absorbed by jejunal enterocytes primarily via the SLC46A1 encoded transporter which is a proton (H+)-coupled transporter more commonly referred to as the proton-coupled folate transporter, PCFT.

Another intestinal folate transporter, that was originally thought to be the major intestinal folate uptake transporter, was originally identified as the reduced folate carrier (RFC). The RFC protein is encoded by the SLC19A1 gene.

Outside of the intestine cellular folate uptake, particularly into cells in the central nervous system, is carried out by the SLC46A1 encoded transporter, RFC. The activity of RFC-mediated folate transport is highest for reduced folates (hence the name) such as 5-methyl-THF with very low affinity for folic acid. The RFC is also utilized in the uptake of the anti-folate drugs such as methotrexate and palatrexate. RFC functions as an antiporter with organic phosphate being transported out of the cell in exchange for folate uptake. Both PCFT and RFC are highly specific for the monoglutamate forms of the folates.

The critical role of the SLC46A1 encoded transporter in intestinal folate absorption is evident in individuals with an inherited form of folate malnutrition (hereditary folate malabsorption, HFM) that results from mutations in the SLC46A1 gene. The SLC46A1 gene is located on chromosome 17q11.2 and is composed of 6 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs with the major apical membrane-localized protein being the larger isoform 1 (459 amino acids).

Interestingly there are transporters of the multidrug resistance family that can efflux folates from the intestinal enterocyte back into the lumen of the intestines. Both the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2; encoded by the ABCC2 gene) and the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP; encoded by the ABCG2 gene) are expressed in the apical membranes of intestinal enterocytes. Both transporters have been shown to efflux folates from intestinal enterocytes and, as such, can compete with the activity of PCFT in folate uptake. Another member of the multidrug resistance protein family, multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 (MRP3; encoded by the ABCC3 gene), is expressed in the basolateral membrane of intestinal enterocytes and transports folic acid and 5-methyl-THF into the blood.

Another important protein involved in folate transport in the adult human is the FOLR1 (folate receptor 1) encoded receptor protein. The FOLR1 gene is located on chromosome 11q13.4 and is composed of 7 exons that generate four different mRNAs either through alternative promoter usage or by alternative splicing, all of which encode the same 257 amino acid precursor protein.

The FOLR1 encoded protein binds folic acid and the reduced folate derivative (5-methyl-THF) facilitating their transport into cells. The FOLR1 protein exists in soluble form as well as bound to membranes via a GPI-linkage.

The FOLR1 gene represents one member of a family of folate receptor genes that are clustered at the 11q13.4 locus. This family includes FOLR1, FOLR2, and FOLR3. The FOLR2 gene is referred to as the fetal folate receptor gene given it was originally identified as being expressed in the placenta. The FOLR2 protein is both secreted and GPI anchored like the FOLR1 protein. The FOLR3 gene is expressed in bone marrow, thymus, and spleen, and its expression is elevated in ovarian and uterine cancers. The FOLR3 protein is exclusively secreted.

When monoglutamate folates are taken up into cells, particularly in the liver and kidney where they can be stored (but also in other cells), they are polyglutamated through the action of the enzyme folylpolyglutamate synthase. Folylpolyglutamate synthase is encoded by the FPGS gene. The FPGS gene is located on chromosome 9q34.11 and is composed of 17 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a different isoform of the enzyme.

The activity of folylpolyglutamate synthase is lowest towards 5-methyl-THF and this prevents this form of the vitamin from being trapped within intestinal enterocytes. Folic acid, which is the form found in fortified foods and supplements is also a poor substrate for folylpolyglutamate synthase accounting for its efficient uptake from the intestines and release to the blood.

Within cells (principally the liver where it is stored) the folic acid found in enriched food and in vitamin supplements is converted first to dihydrofolate (DHF) and then to tetrahydrofolate (THF also H4folate) through the action of dihydrofolate reductase, an NADPH-requiring enzyme. The level of DHFR activity in the human liver is relatively low such that high levels of folic acid intake (such as by megadosing vitamins) can lead to pathological consequences. Several studies have shown increased rates of colon cancer and prostate cancer associated with the intake of large doses of folic acid. However, the lack of folate in the diet, or the lack of folic acid supplementation, is directly correlated to neural tube defects occurring during fetal development.

Dihydrofolate reductase is encoded by the DHFR gene. The DHFR gene is located on chromosome 5q14.1 and is composed of 6 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode distinct protein isoforms.

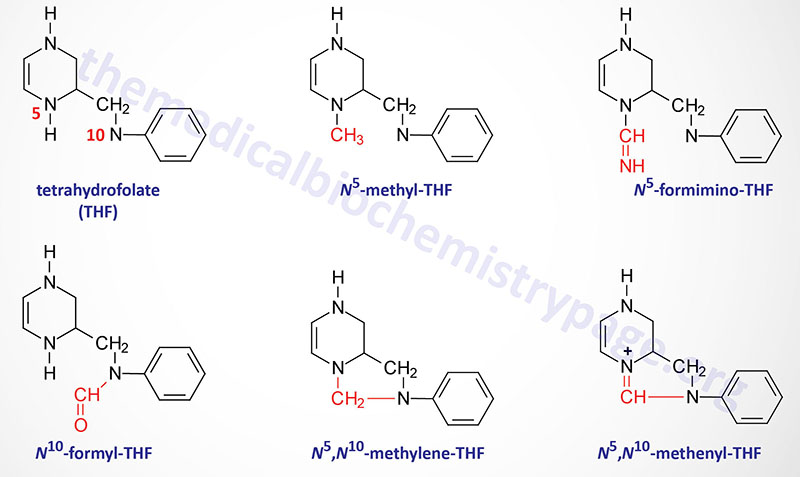

Folate Derivatives

The function of THF derivatives is to carry and transfer various forms of one carbon (1C) units during biosynthetic reactions. The one carbon units are either methyl, methylene, methenyl, formyl, or formimino groups.

Reactions of Folate Derivative Synthesis

There are two distinct pools of THF molecules, the active pool and the reduced pool. The reduced pool consists solely of N5-methyl-THF (5-methyl-THF or simply methyl-THF) which is also the major form of folate absorbed from the small intestines as well as the major form circulating in the blood for transport to the various tissues.

Most of the folate derivatives, excluding 5-methyl-THF, are modified in cells by successive additions of glutamate residues, through the action of folylpolyglutamate synthase as described above. The glutamate residues are added by an amide linkage to the γ-carboxylate group of the folate derivative. The addition of glutamate to folate derivatives traps the molecules in the cell and allows for accumulation in the mitochondria, a process required for the synthesis of glycine.

All of the other THF derivatives constitute the active pool. The active pool forms of THF can be converted to 5-methyl-THF but 5-methyl-THF cannot be used, in any significant capacity, to contribute to the synthesis of the active pool folate derivatives. The major pools of folate derivatives are found in the liver where they are distributed between the cytosol and the mitochondria. The majority of the mitochondrial pool of folate is THF and 10-formyl-THF with less than 10% being 5-methyl-THF and 5-formyl-THF. Within the cytosol nearly 50% of folate is in the 5-methyl-THF form with around 25% being THF and around 25%–30% being combined between the 10-formyl-THF and 5-formyl-THF forms.

N5–N10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate Synthesis

N5,N10-methylene-THF (5,10-methylene-THF) is synthesized from THF and serine by the serine/glycine hydroxymethyltransferases (SHMT1 and SHMT2). The SHMT1 encoded enzyme is cytosolic and the SHMT2 encoded enzyme is mitochondrial. The carbon from serine (specifically carbon 3) represents the major source of the one carbon (1C) units transferred during reactions utilizing THF. Indeed, the ability of serine to be synthesized from the glycolytic intermediate, 3-phosphoglycerate, directly ties glucose metabolism to the active THF pool. The SHMT catalyzed reactions generating 5,10-methylene-THF not only represent the major active THF synthesizing reaction but also represent a major reaction for the conversion of serine to glycine, a reaction that directly ties glycine synthesis to glycolysis. The 5,10-methylene-THF form of folate is required for the synthesis of thymidine nucleotides which directly ties DNA synthesis to glucose metabolism.

N5-Methyltetrahydrofolate Synthesis

The conversion of 5,10-methylene-THF to 5-methyl-THF is catalyzed by methylene THF reductase (encoded by the MTHFR gene). MTHFR is an NADPH-dependent enzyme which serves as the electron donor for the reduction of 5,10-methylene-THF. Mutations in the MTHFR gene results in a form of homocysteinemia that is often referred to as hyperhomocysteinemia.

The MTHFR gene is located on chromosome 1p36.22 and is composed of 13 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode distinct protein isoforms.

N5-Formiminotetrahydrofolate Synthesis

The production of N5-formimino-THF (5-formimino-THF) occurs during the catabolism of histidine and is catalyzed by the transferase activity of the bifunctional enzyme, formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase. Formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase functions as a homooctameric enzyme complex. The 5-formimino-THF is then converted to 5-10-methenyl-THF via the action of the cyclodeaminase activity of the complex with glutamate and ammonia being the other products.

Formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase is encoded by the FTCD gene. The FTCD gene is located on chromosome 21q22.3 which is composed of 16 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, two of which encode the same 541 amino acid protein (isoform A) and the other encodes a protein of 572 amino acids (isoform C).

N10-Formyltetrahydrofolate Synthesis

Synthesis of N10-formyl-THF (10-formyl-THF) can occur by two distinct pathways, both of which utilize the same multifunctional enzyme encoded by the MTHFD1 gene. There are three activities of the MTHFD1 encoded enzyme that include, N5,N10-methenyl-THF (5,10-methenyl-THF) cyclohydrolase, 5,10-methylene-THF dehydrogenase, and 10-formyl-THF synthetase.

In one pathway 5,10-methenyl-THF is converted to 10-formyl-THF and in the other pathway 10-formyl-THF is formed from ATP, formate, and THF. The 10-formyl-THF form of folate is required for the synthesis of the purine nucleotides. The 5,10-methylene dehydrogenase activity of the MTHFD1 encoded enzyme converts 5,10-methylene-THF to 5,10-methenyl-THF.

The MTHFD1 gene is located on chromosome 14q23.3 and is composed of 28 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode distinct protein isoforms.

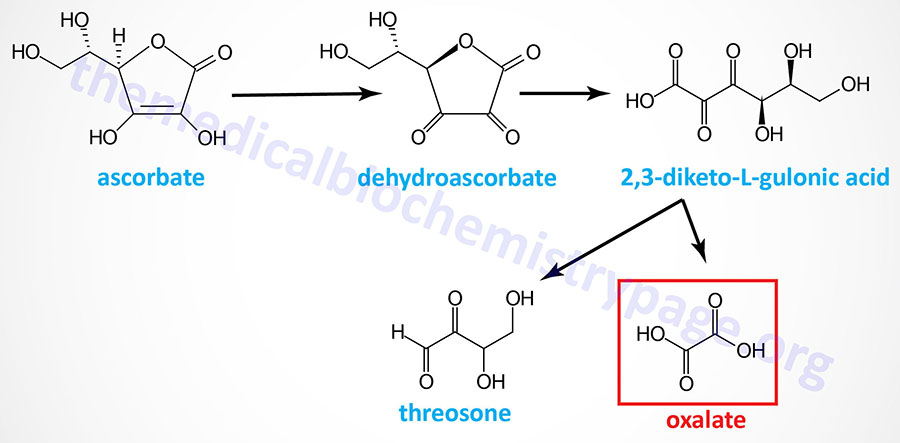

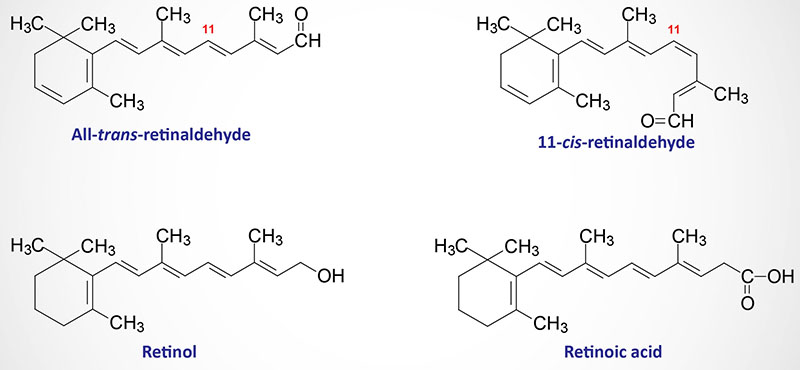

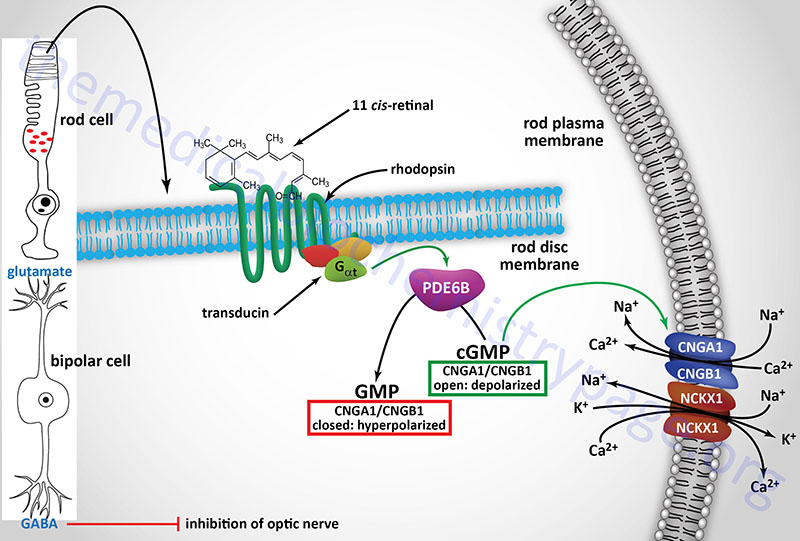

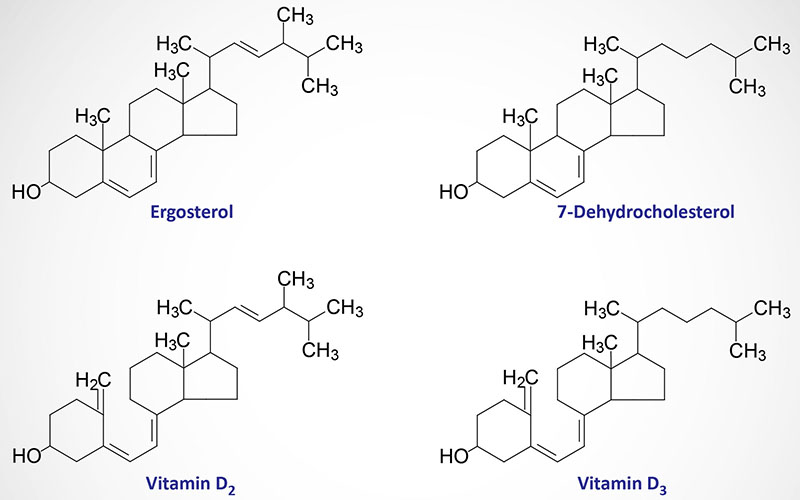

MTHFD1-Related Enzymes