Last Updated: September 12, 2025

Introduction to Tumor Suppressor Genes

Tumor suppressor genes were first identified by making cell hybrids between tumor and normal cells. On some occasions a chromosome from the normal cell reverted the transformed phenotype. Several familial cancers have been shown to be associated with the loss of function of a tumor suppressor gene. The table below lists several of these syndromes. A few of these tumor suppressor genes are described in more detail below. They include the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene (RB), Wilms tumors (WT1), neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF1), familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP), von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL), and those identified through loss of heterozygosity such as in colorectal carcinomas (called DCC for deleted in colon carcinoma) and P53 which was originally thought to be a proto-oncogene. However, the wild-type P53 protein suppresses the activity of mutant alleles of p53 which are the oncogenic forms of P53.

Table of Cancer Syndromes Involving Tumor Suppressor Genes

| Familial Cancer Syndrome | Tumor Suppressor Gene | Function | Chromosomal Location | Tumor Types Observed |

| Li-Fraumeni Syndrome | TP53 | cell cycle regulation, apoptosis | 17p13.1 | brain tumors, sarcomas, leukemia, breast cancer |

| Familial Retinoblastoma | RB1 | cell cycle regulation | 13q14.2 | retinoblastoma, osteogenic sarcoma |

| Wilms Tumor | WT1 | transcriptional regulation | 11p13 | pediatric kidney cancer, most common form of childhood solid tumor |

| Neurofibromatosis Type 1 | NF1 protein = neurofibromin 1 | catalysis of RAS inactivation | 17q11.2 | neurofibromas, sarcomas, gliomas |

| Neurofibromatosis Type 2 | NF2 protein = merlin or neurofibromin 2 | linkage of cell membrane to actin cytoskeleton | 22q12.2 | Schwann cell tumors, astrocytomas, meningiomas, ependymomas |

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis | APC | signaling through adhesion molecules to nucleus | 5q22.2 | colon cancer |

| Tuberous sclerosis 1 | TSC1 protein = hamartin | forms complex with TSC2 protein, inhibits signaling to downstream effectors of mTOR | 9q34 | seizures, intellectual impairment, facial angiofibromas |

| Tuberous sclerosis 2 | TSC2 protein = tuberin | see TSC1 above | 16p13.3 | benign growths (hamartomas) in many tissues, astrocytomas, rhabdomyosarcomas |

| Deleted in Pancreatic Carcinoma 4, Familial juvenile polyposis syndrome | DPC4, also known as SMAD4 | regulation of TGF-β/BMP signal transduction | 18q21.1 | pancreatic carcinoma, colon cancer |

| Deleted in Colorectal Carcinoma | DCC | transmembrane receptor involved in axonal guidance via netrins | 18q21.2 | colorectal cancer |

| Familial Breast Cancer | BRCA1 | functions in transcription, DNA binding, transcription coupled DNA repair, homologous recombination, chromosomal stability, ubiquitination of proteins, and centrosome replication | 17q21.31 | breast and ovarian cancer |

| Familial Breast Cancer | BRCA2: same as the FANCD1 locus | transcriptional regulation of genes involved in DNA repair and homologous recombination | 13q12.3 | breast and ovarian cancer |

| Cowden syndrome | PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog | contains a catalytic domain similar to tyrosine phosphatases but is specific for phosphatidylinositides with the primary activity being phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphophate (PIP3) 3-phosphatase; PTEN activity serves to negatively regulate the AKT/PKB signaling pathway | 10q23.3 | gliomas, breast cancer, thyroid cancer, head & neck squamous carcinoma |

| Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome (PJS) | STK11 (serine-threonine kinase 11), a nuclear localized kinase, is also known as the PJS and LKB1 gene | phosphorylates and activates AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), AMPK involved in stress responses, lipid and glucose metabolism | 19p13.3 | hyperpigmentation, multiple hamartomatous polyps, colorectal, breast, and ovarian cancers |

| Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colon Cancer type 1, HNPCC1 | MSH2 (mutS homolog 2) | DNA mismatch repair | 2p22-p21 | colon cancer |

| Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colon Cancer type 2, HNPCC2 | MLH1 (mutL homolog 1) | DNA mismatch repair | 3p21.3 | colon cancer |

| Familial diffuse-type gastric cancer | CDH1 protein = E-cadherin | cell-cell adhesion protein | 16q22.1 | gastric cancer, lobular breast cancer |

| von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome | VHL | is a component of a ubiquitin ligase complex that ubiquitylates HIF-1α; also involved in inhibition of transcription elongation | 3p25.3 | renal cancers, hemangioblastomas, pheochromocytoma, retinal angioma |

| Familial Melanoma | CDKN2A = tumor suppressor: protein = cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A gene produces 2 proteins: p16INK4 and p14ARF | p16INK4 inhibits cell-cycle kinases CDK4 and CDK6; p14ARF binds the p53 stabilizing protein MDM2 | 9p21 | melanoma, pancreatic cancer, others |

| Gorlin Syndrome: Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) | PTCH protein = patched | transmembrane receptor for sonic hedgehog (shh), involved in early development through repression of action of smoothened | 9q22.3 | basal cell skin carcinoma |

| Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 | MEN1 protein = menin | serves as a scaffold protein for processes of histone modification | 11q13 | parathyroid and pituitary adenomas, islet cell tumors, carcinoid |

P53

Loss of heterozygosity at the short arm of chromosome 17 has been associated with tumors of the lung, colon and breast. This region of chromosome 17 includes the gene (TP53) encoding p53. The inheritance of a mutated TP53 allele is the cause of Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS). LFS is a disorder that greatly increases the risk of several types of cancer including sarcomas, breast cancers, acute leukemias and brain tumors. The disorder is named for the two physicians who first recognized and described the syndrome: Frederick Pei Li and Joseph F. Fraumeni, Jr.

The TP53 gene was originally discovered because the protein product complexes with the SV40 large T antigen. It was first thought that TP53 was a dominant oncogene since cDNA clones isolated from tumor lines were able to cooperate with the RAS oncogene in transformation assays. This proved to be misleading since the cDNA clones used in all these studies were mutated forms of wild-type p53 and cDNAs from normal tissue were later shown to be incapable of RAS co-transformation. The mutant p53 proteins were shown to be altered in stability and conformation as well as binding to hsp70.

Functional p53 exists as a homotetramer and as such can include both wild-type and mutant monomeric p53 peptides resulting in dominant-negative effects from mutations in the p53 gene. Subsequent analysis of several murine leukemia cell lines showed that the p53 locus was lost by either insertions or deletions on both alleles. This suggested that wild-type p53 may be a tumor suppressor not a dominant proto-oncogene. Direct confirmation came when it was shown that wild-type p53 could suppress transformation in oncogene cooperation assays with mutant p53 and Ras. It has now been demonstrated that mutation at the TP53 locus occurs in cancers of the colon, breast, liver and lung. Indeed, p53 involvement in neoplasia is more frequent than any other known tumor suppressor or dominant proto-oncogene.

The TP53 gene is located on chromosome 17p13.1 and is composed of 12 exons that generate multiple transcripts as a result of alternative promoter usage and alternative splicing. In addition, multiple p53 isoforms result from the use of alternative translational start codons in the various mRNAs.

The protein encoded by TP53 is a nuclear localized phosphoprotein. A domain near the N-terminus of the p53 protein is highly acidic like similar domains found in various transcription factors. When this domain is fused to the DNA-binding domain of the yeast GAL4 protein, the resulting chimera is able to activate transcription from genes containing GAL4 response elements. This suggested that p53 is likely to be involved in transcriptional regulation. Indeed, sequences at the N-terminus of the p53 protein have been shown to function as a transcription activator. Subsequent research demonstrated that p53 regulates the transcription of genes involved in suppression of cell growth. p53 binds to DNA sequences containing two copies of the motif: 5′-PuPuC(A/T)(A/T)GPyPyPy-3′ (Pu = any purine; Py = any pyrimidine). This sequence motif indicated that that p53 bound to DNA as a homotetramer. Binding as a tetrameric complex explains the fact that mutant p53 proteins act in a dominant manner to interfere with the activity of wild-type proteins present in the tetrameric complex.

Like pRB, p53 forms a complex with SV40 large T antigen, as well as the E1B transforming protein of adenovirus and E6 protein of human papilloma viruses. Complexing with these tumor antigens increases the stability of the p53 protein. This increased stability of p53 is characteristic of mutant forms found in tumor lines. The complexes of T antigens and p53 renders p53 incapable of binding to DNA and inducing transcription.

A cellular protein, originally identified in a spontaneous transformed mouse cell line and termed MDM2, has been shown to bind to p53. Complexing of p53 and MDM2 results in loss of p53 mediated transactivation of gene expression. Significantly, amplification of the MDM2 gene is observed in a significant fraction of most common human sarcomas. The MDM2 protein is a key regulator of p53 function. The MDM2 protein is a member of the large family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. When associated with p53 the MDM2 protein ubiquitylates p53. This ubiquitylation leads to proteasome-mediated degradation of p53.

Several other ubiquitin ligases ensure that p53 activity is kept in check by ensuring it has a very short half-life in the cells. These other ubiquitin ligases include RING finger and CHY zinc finger domain containing 1, RCHY1 (also known as p53-induced RING-H2, PIRH2), STIP1 homology and U-box containing protein 1, STUB1 (also known as C-terminus of Hsc70 interacting protein, CHIP), and RING finger and WD repeat domains-containing protein 2, RFWD2 (also known as constitutive photomorphogenesis protein 1, COP1). The transcriptional activity of p53 is also regulated by having the NEDD8 protein attached (termed neddylation) in a manner similar to ubiquitylation. Indeed, neddylation of p53 is catalyzed by the E3 ligase activity of MDM2. In contrast to ubiquitylation, which targets p53 for proteasome degradation, neddylation inhibits the transcriptional activity of p53.

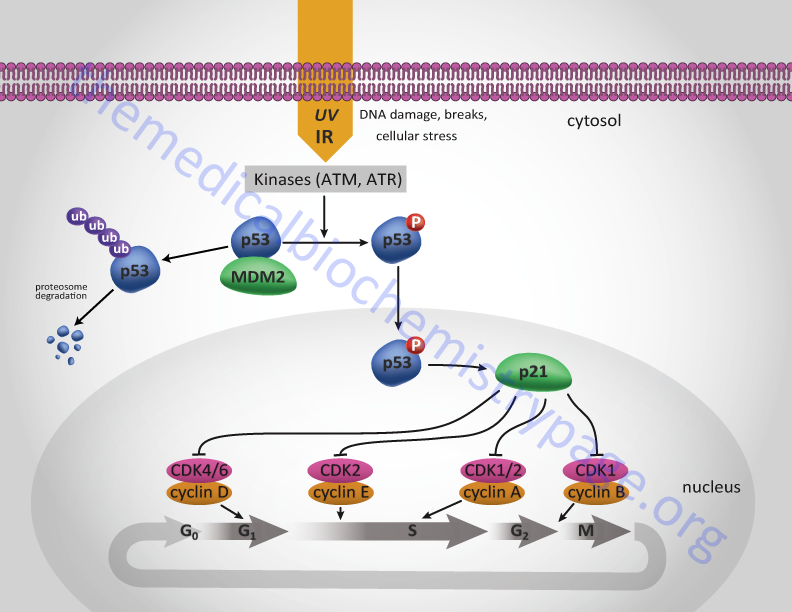

The transcriptional activity of p53 is regulated by various post-translational mechanisms including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, and as indicated by ubiquitylation and neddylation. Under normal cellular conditions the level of p53 is low following mitosis but increases during G1. During S-phase the protein becomes phosphorylated by the M-phase cyclin-CDK complex of the cell cycle. This phosphorylation of p53 allows it to dissociate from MDM2 and migrate to the nucleus and activate the expression of target genes (see Figure below).

Under conditions of cellular stress, or when DNA is damaged by ionizing or uv irradiation, various kinases become activated and result in the hyperphosphorylation of p53 dramatically increasing p53-mediated transcription. These stress-induced and DNA damage-induced kinases include ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM), ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR), casein kinase I (CKI), and AMPK. One major cell-cycle regulating gene that is a target for p53 is the CDK inhibitory protein (CIP), p21CIP. Activation of p53, particularly in response to stress or DNA-damage, results in increased expression of p21CIP. Expression of p21CIP leads to cell cycle arrest at several points as indicated in the Figure below.

Retinoblastoma (RB)

In the familial form of retinoblastoma individuals inherit a mutant, loss of function allele from an affected parent. A subsequent later somatic mutational event (referred to as loss of heterozygosity, LOH) inactivates the normal allele resulting in retinoblastoma development. This leads to an apparently dominant mode of inheritance. The requirement for an additional somatic mutational event at the unaffected allele means that penetration of the defect is not always complete. Indeed, the penetration frequency for retinoblastoma is not 100% but closer to 90%, meaning not all individuals who inherit, what is supposed to be genetically a dominant disease, actually develop retinoblastoma. In addition, due to the terminal differentiation of pigmented retinal epithelial cells, if a child does not suffer a somatic mutation in the wild-type RB gene before the age of 6-8 they will never develop the disease. In the sporadic forms of retinoblastoma involving the RB locus, two somatic mutational events must occur, the second of which must occur in the descendants of the cell receiving the first mutation. This combination of mutational events is extremely rare.

The retinoblastoma gene is identified as RB1 and it was originally identified through cytological assay. The RB1 gene is located on chromosome 13q14.2 and is composed of 28 exons that encode a protein of 928 amino acids that make up a 110 kDa protein. Two of the introns in the RB1 gene are extremely large, 35 kb and 70 kb. The pRB protein is a nuclear localized phosphoprotein. pRB is not detectable in any retinoblastoma cells. However, surprisingly detectable levels of pRB can be found in most proliferating cells even though there is a restricted number of tissues affected by mutations in the RB gene (i.e. retina, bone and connective tissue). Subsequent to the isolation and characterization of the RB1 gene, two additional RB-related proteins and their encoding genes were characterized. The related proteins were initially identified by their molecular weights and given designations of p107 and p130. The gene encoding p107 is the RB-like 1 (RBL1) gene and the gene encoding p130 is the RBL2 gene. These three related proteins are referred to as the pocket protein family.

Many different types of mutations occur to result in loss of pRB function. The largest percentage (30%) of retinoblastomas contain large scale deletions. Splicing errors, point mutations and small deletions in the promoter region have also been observed in some retinoblastomas. The germ line mutations at RB1 occur predominantly during spermatogenesis as opposed to oogenesis. However, the somatic mutations occur with equal frequency at the paternal or maternal locus. In contrast, somatic mutations at RB1 in sporadic osteosarcomas occur preferentially at the paternal locus. This may be the result of genomic imprinting.

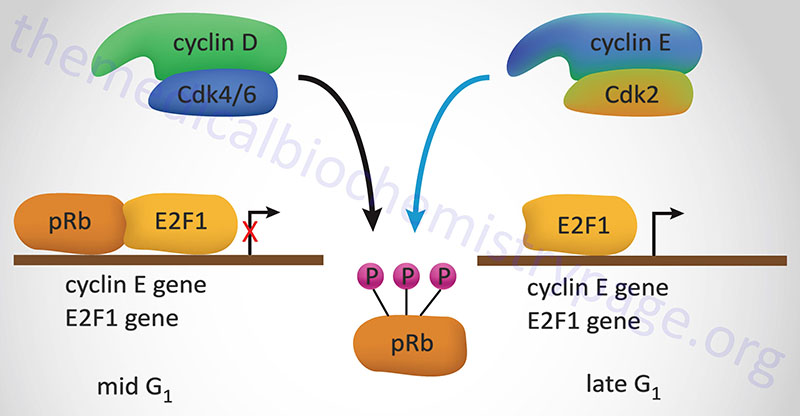

The major function of pRB is in the regulation of cell cycle progression. Its ability to regulate the cell cycle correlates to the state of phosphorylation of pRB. Phosphorylation is maximal at the start of S phase and lowest after mitosis and entry into G1. Stimulation of quiescent cells with mitogen induces phosphorylation of pRB, while in contrast, differentiation induces hypophosphorylation of pRB. It is, therefore, the hypophosphorylated form of pRB that suppresses cell proliferation.

One of the most significant substrates for phosphorylation by the G1 cyclin-CDK complexes that regulate progression through the cell cycle is pRB. pRB forms a complex with proteins of the E2F family of transcription factors, a result of which renders E2F inactive. The original E2F proteins was so-called due to its binding to the adenovirus E2 promoter. When pRB is phosphorylated by G1 cyclin-CDK complexes it is released from E2F allowing E2F to transcriptionally activate genes.

In the context of the cell cycle, E2F increases the transcription of the S-phase cyclins as well as leads to increases in its’ own transcription. There are six members of the E2F family identified as E2F1–E2F6. The proteins E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3 are regulated by pRB, whereas E2F4 and E2F5 are regulated by p107 (RBL1) and p130 (RBL2). The E2F6 encoded protein lacks the transactivation domain and the tumor suppressor domain found in the other five members of the family. When released from pocket proteins the E2F transcription factors can form homodimers and bind to target DNA sequences or they can form heterodimers to activate transcription. When forming heterodimers the E2F proteins interact with proteins of the dimerization partner (DP) family. Humans express three DP family member genes identified as TFDP1 (transcription factor DP-1), TFDP2, and TFDP3.

One element in the growth suppressive pathway of pRB involves the MYC gene. Proliferation of keratinocytes by TGF-β is accompanied by suppression of MYC expression. The inhibition of MYC expression can be abrogated by introducing vectors that express the SV40 and adenovirus large T antigens which bind pRB. Therefore, a link exists between TGF-β, pRB and MYC expression in keratinocytes.

Transformation by the DNA tumor viruses, SV40, adeno, polyoma, human papilloma and BK is accomplished by binding of the transforming proteins of these viruses to pRB when pRB is in the hypophosphorylated (and thus the proliferation inhibitory) state.

Wilms Tumor (WT1)

Wilms tumor is a form of nephroblastoma that gets its name from the German surgeon, Max Wilms, who first described the condition. This childhood cancer is the most common form of solid tumor in children with a frequency of approximately 1 in 10,000. In addition, Wilms tumor accounts for 8% of all childhood cancers. The cancer results from the malignant transformation of abnormally persistent renal stem cells. Several different genetic loci have been associated with the development of Wilms tumor with the most prominent being located on chromosome 11. Either one (unilateral) or both (bilateral) kidneys can be involved. Sporadic evolution of Wilms tumors is associated with chromosomal deletions, identified cytogenetically, at both 11p13 and 11p15. The 11p15 deletions may involve the IGF-2 or HRAS genes. There are also familial forms of Wilms tumor that do not involve either locus.

The potential Wilms tumor gene at 11p13 is found in a deleted region of about 345 kb. This region contains a single transcription unit identified as WT1 that spans 50–60 kb and contains 12 exons that generate six alternatively spliced WT1 mRNAs. Adding to the complexity and difficulty in assigning a function to the WT1 locus is that as a consequence of alternative splicing, alternative translational start codon usage, and RNA editing, there are at least 24 different isoforms of WT1 protein.

Several functional domains have been identified in each of the WT1 proteins. The differences between many of the encoded proteins is not striking but differential interactions between the WT1 proteins with distinct targets may result some level of differential control. The first hint of the potential function for WT1 came from the identification of four zinc finger domains suggesting it to be a transcription factor. Several protein forms have a three amino acid insertion (KTS) between the third and fourth zinc finger domains. Additional forms have an additional 17 amino acid sequence in exon 5 due to alternative splicing. There is a potential leucine zipper motif in the center of the protein indicating that WT1 may associate other leucine zipper containing proteins. The N-terminal 180 amino acids are involved in self-association. The WT1 proteins can act as transcriptional activators or repressors dependent upon the cellular or chromosomal context.

Several other genes or chromosomal regions have been shown to be associated with Wilms tumor and these have been identified as WT2 (chromosome 11p15.5), WT3 (chromosome 16q), WT4 (chromosome 17q12–q21), and WT5 (chromosome 7p15–p11.2). Mutations in BRCA2, glipican-3 (GPC3), and WTX (an X chromosome allele) have also been described in Wilms tumor.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1)

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is also known as von Recklinghausen disease due to the fact that the German pathologist, Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen, first characterized the disorder in 1882. NF1 is classified as a tumor predisposition syndrome characterized by the development of multiple neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots and Lisch nodules. The incidence of NF1 is quite common occurring at a rate of 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 5,000 individuals worldwide. All cases of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) arise through the acquisition of an autosomal dominant mutant allele. Approximately half of all individuals with NF1 inherit a mutant allele from one of their parents with the other 50% of all affected individuals acquiring the disorder as a result of new mutations. Given the characteristic pathology of patients with mutations in the NF1 locus, the encoded protein was identified as neurofibromin. Some patients also develop benign pheochromocytomas and CNS tumors. A small percentage of patients develop neurofibrosarcomas which are likely to be Schwann cell derived. Although NF1 is a fully penetrant disease there is a high degree of phenotypic variability even within individuals in the same family harboring the same mutation in the NF1 gene.

Assignment of the NF1 gene to chromosome 17q11.2 was done by linkage studies of affected pedigrees. The NF1 gene is extremely large, spanning 350 kbp of DNA and encompassing a total of 62 exons, 58 of these exons are constitutive and the remaining four (9a, 10a-2, 23a, and 28a) are involved in alternative splicing. The NF1 gene generates at least three alternatively spliced mRNAs. In addition to alternative splicing from the NF1 gene there are three additional genes located within exon 27b that are transcribed in the opposite direction relative to transcription of NF1 mRNAs. These three genes are EVI2A (ecotropic viral integration site 2A), EVI2B (ecotropic viral integration site 2B), and OMG (oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein).

Of the three primary NF1 transcripts, the NF1 isoform 1 mRNA encodes the largest protein isoform consisting of 2839 amino acids. The isoform 1 mRNA is also subject to RNA editing where a cytidine at position 1306 is edited by a cytidine deaminase to a uridine resulting in the conversion of a CGA codon to a UGA termination codon. In addition to alternative splicing alternative translational start site usage has also been identified.

Characterization of NF1 protein isoforms has allowed for the identification of at least six distinct protein isoforms all of which are identified as neurofibromin. The two major protein isoforms are identified as neurofibromin I and II. Neurofibromin I is predominantly expressed in the brain and neurofibromin II is predominantly expressed in Schwann cells. Neurofibromin III contains exon 48a while neurofibromin IV contains exons 23a and 48a. Neurofibromin III and IV are primarily expressed in cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle and are implicated in normal muscle and cardiac development. Two additional neurofibromin isoforms have been described. One isoform contains exon 9a is expressed mainly in neurons of the forebrain. This isoform is suspected to be involved in memory and learning mechanisms. The other additional isoform has alternative exon 10a-2 inserted which introduces a transmembrane domain. The function of this latter variant is unclear but it is found in most tissues.

Characterization of NF1 protein isoforms has allowed for the identification of at least six distinct protein isoforms all of which are identified as neurofibromin. The two major protein isoforms are identified as neurofibromin I and II. Neurofibromin I is predominantly expressed in the brain and neurofibromin II is predominantly expressed in Schwann cells. Neurofibromin III contains exon 48a while neurofibromin IV contains exons 23a and 48a. Neurofibromin III and IV are primarily expressed in cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle and are implicated in normal muscle and cardiac development. Two additional neurofibromin isoforms have been described. One isoform contains exon 9a is expressed mainly in neurons of the forebrain. This isoform is suspected to be involved in memory and learning mechanisms. The other additional isoform has alternative exon 10a-2 inserted which introduces a transmembrane domain. The function of this latter variant is unclear but it is found in most tissues.

Initial characterization of neurofibromin showed that it is most abundantly expressed in the nervous system. Immunostaining of tissue sections demonstrated that neurofibromin immunoreactivity was detectable in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells. The primary function of neurofibromin is due to the presence of a Ras GTPase activating domain (RasGAP) which confers rapid inactivation of the Ras monomeric G-protein, thereby negatively regulating the Ras/MAPK signal transduction cascade. The RasGAP domain in NF1 is called the GAP-related domain, GRD.

Neurofibromin also contains two additional functional domains, a plekstrin homology-like (PH) domain and a Sec14 homology-like domain. The PH domain is a domain of approximately 120 amino acids that is found in numerous proteins. PH domains interact with membrane phosphatidylinositols allowing for membrane targeting of PH domain containing proteins. The Sec14 domain is another phospholipid binding domain. Of significance to neural function, these domains in neurofibromin allow it to interact with the protein complex that is responsible for the trafficking of glutamate receptors to the synaptic membrane of nerve cells. The specific glutamate receptors are the GRIN2B encoded NMDA receptor subunits. Neurofibromin is also involved in regulation of synaptic transmission via modulation of adenylate cyclase activity.

In schwannoma cell lines from patients with neurofibromatosis, loss of neurofibromin is associated with impaired regulation of the GTP-bound form of the proto-oncogene RAS (RAS-GTP). Analysis of other neural crest-derived tumor cell lines showed that some melanoma and neuroblastoma cell lines established from tumors occurring in patients without neurofibromatosis also contained reduced or undetectable levels of neurofibromin, with concomitant genetic abnormalities of the NF1 locus. In contrast to the schwannoma cell lines, however, RAS-GTP was appropriately regulated in the melanoma and neuroblastoma lines that were deficient in neurofibromin. These results demonstrate that some neural crest tumors not associated with neurofibromatosis have acquired somatically inactivated NF1 genes and suggested a tumor-suppressor function for neurofibromin that is independent of RAS GTPase activation.

Development of benign neurofibromas versus malignant neurofibrosarcomas may be the difference between inactivation of one NF1 allele versus both alleles, respectively. However, changes other than at the NF1 locus are clearly indicated in the genesis of neurofibrosarcomas. A consistent loss of genetic material on the short arm of chromosome 17 is seen in neurofibrosarcomas but not neurofibromas. The losses at 17p affect the wild type p53 locus (TP53) and may be associated with a mutant p53 allele on the other chromosome.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP)

Somatic mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene appear to initiate colorectal cancer development in the general population, whereas it is germ line mutations that are responsible for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). FAP represents a dominantly inherited form of colorectal carcinoma. Multiple colonic polyp development characterizes the disease. These polyps arise during the second and third decades of life and become malignant carcinomas and adenomas later in life. Genetic linkage analysis assigned the APC locus to chromosome 5. This region of the chromosome is also involved in nonfamilial forms of colon cancer. FAP adenomas appear as a result of loss-of function mutations to the APC gene, a characteristic of all tumor suppressors.

Identification of the APC gene was aided by the observation that two patients harbored deletions at the 5q21 locus that spanned 100 kb of DNA. Three candidate genes in this region, DP1, SRP19 and DP2.5 were examined for mutations that could be involved in APC. The DP2.5 gene has sustained four distinct mutations specific to APC patients indicating this to be the APC gene. To date, more than 120 different germ line and somatic mutations have been identified in the APC gene. The vast majority of these mutations lead to C-terminal truncation of the APC protein.

The APC gene is located on chromosome 5q22.2 and contains 20 exons that generate 15 alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode 13 distinct isoforms of the APC protein. No similarities between the APC proteins and other known proteins has been found except for several stretches of sequence related to intermediate filament proteins.

Using antibodies specific for the N-terminus of APC, it is possible to co-precipitate additional APC-associated proteins. One of these APC-associated proteins is β-catenin (encoded by the CTNNB1 gene). The catenins are a family of proteins that interact with the cytoplasmic portion of the cadherins (cell-cell adhesion family of proteins), thus linking the cadherins to the actin cytoskeleton. Catenins are equally important in the signaling cascade initiated by the Wnt family of proteins that are involved in embryonic patterning and development of the nervous system.

The Wnt proteins are secreted factors that interact with cell-surface receptors that are members of the Frizzled family of proteins. Wnt-receptor interaction induces the activity of the cytoplasmic phosphoprotein dishevelled. Activated dishevelled inhibits the serine/threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β). When GSK-3β is inhibited, β-catenin becomes hypophosphorylated. The hypophosphorylated form of β-catenin migrates to the nucleus and interacts with transcription factors of T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) family, thereby, inducing expression of various target genes. There are four TCF genes in mammalian cells. They are identified as TCF7 (also known as TCF-1), LEF1, TCF7L1 (also known as TCF-3), and TCF7L2 (also known as TCF-4). The role of APC in this pathway is to bind phosphorylated β-catenin. The APC-β-catenin complex stimulates the breakdown of β-catenin. Therefore, mutations which lead to a loss of APC, or to a loss of the portion of the APC protein that interacts with β-catenin, result in constitutive activation of TCF/LEF-1 and unrestricted growth.

Deleted in Colon Carcinoma (DCC)

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on chromosome 18 is frequently observed in colorectal carcinomas (73%) and in advanced adenomas (47%), but only occasionally in earlier-stage adenomas (11%–13%). The area of chromosome 18 which is observed to be lost resides between 18q21 and the telomere. A 370 kbp stretch of DNA from the region of 18q suspected to contain the tumor suppressor gene was cloned. Evaluation of sporadic colon cancers for allelic deletions in this defined area of chromosome 18 identified two candidate tumor suppressors. One was DPC4 (see Table above) and the other was DCC (for deleted in colorectal carcinoma). DPC4 is deleted in up to one-third of cases assayed and DCC, or a closely linked gene, was deleted in the remaining tumors. Tumor suppressor genes located on chromosome 17p and 18q are critically involved in the development of most gastric cancers. Involvement of DCC may be rather selective for gastrointestinal cancers. Loss of DCC gene expression is also an important factor in the development or progress of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Expressed exons from the 18q21 region were used as probes for screening cDNA libraries to obtain clones that encoded the gene which was given the name DCC. A YAC contig, containing the entire DCC coding region, was characterized showing that the DCC gene spans approximately 1.4 Mbp. The DCC gene is officially identified as DCC netrin 1 receptor.

The DCC gene is located on chromosome 18q21.2 and is composed of 32 exons that encode a 1447 amino acid protein. Expression of the DCC gene has been detected in most normal tissues, including colonic mucosa. Somatic mutations have been observed within the DCC gene in colorectal cancers. The types of mutations seen included a homozygous deletion of the 5′ end, a point mutation within one of the introns, and 10 examples of DNA insertions within a 170 bp fragment immediately downstream of one of the exons.

The DCC protein is a transmembrane protein of the immunoglobulin superfamily and has structural features in common with certain types of cell-adhesion molecules, including neural-cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM). It is known that the establishment of neuronal connections requires the accurate guidance of developing axons to their targets. This guidance process involves both attractive and repulsive cues in the extracellular environment. The netrins and semaphorins are proteins that can function as diffusible attractants or repellents for developing neurons. However, the receptors and signal transduction mechanisms through which they produce their effects are poorly understood. Netrins are chemoattractants for commissural axons in the vertebral spinal cord. Recent work has shown that DCC is expressed on spinal commissural axons and possesses netrin-1-binding activity. Indeed, the DCC protein is now known to be a receptor that mediates the effects of netrin-1 on commissural axons.

Genetic evidence showing an interaction between DCC and netrin homologs in C. elegans (the UNC-40 protein) and Drosophila melanogaster (the frazzled protein) supports the role of DCC as a receptor in the axonal guidance pathway. Mice carrying a null allele of DCC harbor defects in axonal projections that are similar to those seen in netrin-1-deficient mice, further supporting the interaction between DCC and axon development. However, the DCC-deficient mice exhibited no effects on intestinal growth, differentiation or morphogenesis which fails to demonstrate a tumor-suppressor role for DCC.

DCC has been shown to induce apoptosis in the absence of ligand binding, but blocks apoptosis when engaged by netrin-1. Furthermore, DCC is a caspase substrate, and mutation of the site at which caspase-3 cleaves DCC suppresses the pro-apoptotic effect of DCC completely. DCC may function as a tumor-suppressor protein by inducing apoptosis during metastasis or tumor growth beyond the local blood supply, both of which are conditions that lack the DCC ligand. This would likely occur through functional caspase cascades leading to cleavage of DCC.

von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome (VHL)

Like many diseases caused by loss of tumor suppressor gene activity, individuals afflicted with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL) inherit one normal copy and one mutant copy of the VHL gene. As a consequence of somatic mutation or loss of the normal VHL gene, individuals are predisposed to a wide array of tumors that include renal cell carcinomas, retinal angiomas, cerebellar hemangioblastomas and pheochromocytomas. In addition, some individuals with VHL syndrome sustain somatic alterations to both wild-type genes. This latter phenomenon is evident in the majority of sporadic clear cell renal carcinomas.

One characteristic feature of tumors from VHL syndrome patients is the high degree of vascularization, primarily as as result of the constitutive expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene. Many of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) controlled genes are also constitutively expressed in these tumors whether or not high oxygen levels are present. Details of the HIF-1 pathway in cancer cell metabolism can be found in the Metabolic Alterations Associated with Cancer page as well as the Glycolysis and the Regulation of Blood Glucose page. In addition, the VHL gene has been shown to be required for cells to exit out of the cell cycle during nutrient depletion. The VHL gene is located on chromosome 3p25.3 and is composed of 4 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNA generating two isoforms of pVHL. The VHL-encoded protein isoform 1 is a 213 amino acid protein and isoform 2 is a 172 amino acid protein.

The role of the proteins encoded by the VHL gene (pVHL) has been deduced from studies on the alterations in HIF-1 control of hypoxia-inducible genes in VHL tumors. HIF-1 is a heterodimeric complex composed of an α-subunit and a β-subunit. The β-subunit is constitutively expressed while the α-subunit expression and activity are increased in response to changes in cellular oxygen content. There are three related HIF complexes identified as HIF-1, HIF-2, and HIF-3 that are defined by the particular α-subunit of the complex. The activity of the HIF-1 and HIF-2 complexes are highly similar in their responses to hypoxia. Less detail is known regarding the HIF-3 complex.

Humans express three α-subunit genes, HIF1α (HIF1A gene), HIF2α (EPAS1 gene, for endothelial PAS domain protein 1), and HIF3α (HIF3A gene). The PAS domain is so-called because of the three proteins in which the domain was originally identified: Per (period circadian protein), ARNT (aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator), and Sim (simple-minded protein).The original β-subunit (HIF1β) was initially identified and characterized as ARNT. Humans express two ARNT-related genes (ARNT2 and ARNTL), however, the encoded proteins are not components of the HIF complexes.

Normally the HIF-1α subunits are degraded in the presence of oxygen due to polyubiquitylation. Polyubiquitylation is a key modification directing proteins for rapid degradation by the proteasome machinery. Cells lacking pVHL do not ubiquitylate HIF1α. These observations led to the identification that pVHL was a component of a ubiquitin ligase complex that is responsible for polyubiquitylation of HIF1α subunits. Specifically the pVHL proteins possess ubiquitin E3 ligase activity.

The pVHL proteins also bind to proteins of the elongin family, specifically elongin B and elongin C. Both elongin B and elongin C are components, along with elongin A/A2, of the transcription factor B complex. The transcription factor B complex is responsible for controlling transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Elongin A is the enzymatically active component of the trancription factor B complex, whereas elongin B and elongin C act as regulatory proteins. The interaction of pVHL with this complex results in the inhibition of transcriptional elongation.

pVHL has also been implicated in additional functions. With respect to cell cycle control, pVHL has been implicated in the downregulation of cyclin D1 which would explain why VHL tumor cells fail to exit the cell cycle on nutrient deprivation.