Last Updated: January 28, 2026

Intestinal Uptake of Lipids

In order for the body to make use of dietary lipids, they must first be absorbed from the small intestine. A complete discussion of lipid digestion and absorption is presented in the Digestion and Digestive Processes page. The predominant form of dietary lipid in the human diet is triglyceride. Since these molecules are oils, they are essentially insoluble in the aqueous environment of the intestine. The solubilization (or emulsification) of dietary lipids is accomplished principally in the small intestine by means of the bile acids. Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and then stored in the gallbladder. Following the ingestion of food, bile acids are released and secreted into the gut. Some lipid emulsification occurs in the stomach due to the churning action in this organ which renders some of the lipid accessible to gastric lipase.

The emulsification of dietary fats renders them accessible to various pancreatic lipases in the small intestine. These lipases, pancreatic lipase and pancreatic phospholipase A2 (PLA2), generate free fatty acids and a mixture of mono- and diglycerides from dietary triglycerides. Pancreatic lipase degrades triglyceride at the sn-1 and sn-3 positions sequentially to generate 1,2-diacylglycerides (DAG) and 2-acylglycerides. Phospholipids are degraded at the sn-2 position by pancreatic PLA2 releasing a free fatty acid and a lysophospholipid. The products of pancreatic lipases then enter the intestinal epithelial cells via the action of various transporters as well as by simple diffusion. Within the enterocyte the lipids are used for re-synthesis of triglycerides.

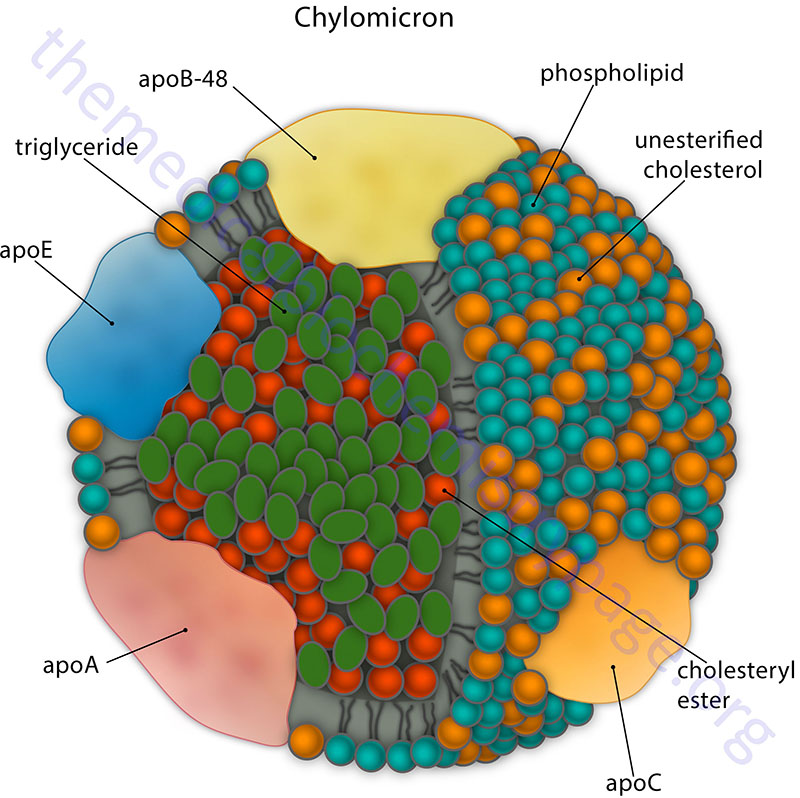

Dietary triglyceride and cholesterol, as well as triglyceride and cholesterol synthesized by the liver, are solubilized in lipid-protein complexes. These complexes contain triglyceride lipid droplets and cholesteryl esters surrounded by the polar phospholipids and proteins identified as apolipoproteins. These lipid-protein complexes, termed lipoproteins, vary in their content of lipid and protein.

There are three major classes of lipoproteins, one of which is dietary in origin and the other two are considered endogenous lipoproteins. Dietary lipoproteins are the chylomicrons. The endogenous lipoproteins are those produced by the liver (very low density lipoprotein: VLDL) and those produced in the circulation (high density lipoprotein: HDL). The assembly of chylomicrons and VLDL occurs within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in enterocytes and hepatocytes, respectively.

During the course of transport in the vasculature, coupled with the action of various vascular lipases (predominantly lipoprotein lipase, LPL), VLDL are converted to intermediate density lipoproteins (IDL) and then to low density lipoproteins (LDL). As a result of the changes in composition and size, vascular lipoproteins are often indicated to exist in five major groups; chylomicron, VLDL, IDL, LDL, and HDL. Because chylomicrons and VLDL contain a large amount of triglyceride these lipoproteins are commonly classified as the triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, TRL.

Another lipid-protein complex in the vasculature is composed of the free fatty acids released from adipose tissue bound to albumin, although these complexes are not strictly defined as lipoproteins.

Table of the Composition of Lipoprotein Complexes

| Complex | Source | Density (g/ml) | %Protein | %TGa | %PLb | %CEc | %Cd | %FFAe |

| Chylomicron | Intestine | <0.95 | 1-2 | 85-88 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| VLDL | Liver | 0.95-1.006 | 7-10 | 50-55 | 18-20 | 12-15 | 8-10 | 1 |

| IDL | VLDL | 1.006-1.019 | 10-12 | 25-30 | 25-27 | 32-35 | 8-10 | 1 |

| LDL | VLDL | 1.019-1.063 | 20-22 | 10-15 | 20-28 | 37-48 | 8-10 | 1 |

| *HDL2 | Intestine, liver (chylomicrons and VLDL) | 1.063-1.125 | 33-35 | 5-15 | 32-43 | 20-30 | 5-10 | 0 |

| *HDL3 | Intestine, liver (chylomicrons and VLDL) | 1.125-1.21 | 55-57 | 3-13 | 26-46 | 15-30 | 2-6 | 6 |

| ++Albumin-FFA | Adipose tissue | >1.281 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

aTriglycerides, bPhospholipids, cCholesteryl esters, dFree cholesterol, eFree fatty acids

*HDL2 (HDL2) and HDL3 (HDL3) are derived from nascent HDL as a result of the acquisition of numerous proteins (such as apolipoproteins), cholesteryl esters, and triglycerides

++ Free fatty acids transported bound to albumin are strictly not classified as lipoprotein particles

Lipid Profile Values

Standard fasting blood tests for cholesterol and lipid profiles will include values for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (so-called “good” cholesterol), LDL cholesterol (so-called “bad” cholesterol) and triglycerides. Family history and life style, including factors such as blood pressure and whether or not one smokes, affect what would be considered ideal versus non-ideal values for fasting blood lipid profiles. Included here are the values for various lipids that indicate low to high risk for coronary artery disease.

Total Serum Cholesterol

- <200mg/dL = desired values

- 200–239mg/dL = borderline to high risk

- 240mg/dL and above = high risk

HDL Cholesterol

- With HDL cholesterol the higher the better

- <40mg/dL for men and <50mg/dL for women = higher risk

- 40–50mg/dL for men and 50–60mg/dL for woman = normal values

- >60mg/dL is associated with some level of protection against heart disease

LDL Cholesterol

- With LDL cholesterol the lower the better

- <100mg/dL = optimal values

- 100mg/dL–129mg/dL = optimal to near optimal

- 130mg/dL–159mg/dL = borderline high risk

- 160mg/dL–189mg/dL = high risk

- 190mg/dL and higher = very high risk

Triglycerides

- With triglycerides the lower the better

- <150mg/dL = normal

- 150mg/dL–199mg/dL = borderline to high risk

- 200mg/dL–499mg/dL = high risk

- >500mg/dL = very high risk

Apolipoproteins

The proteins that are components of the various lipoprotein complexes are referred to as apolipoproteins. Apolipoproteins bind to and aid in the transport of lipids such as triglycerides, cholesterol, phospholipids, and fat soluble vitamins. Apolipoproteins also interact with lipoprotein receptors on cells as well as other lipid transport proteins. Most apolipoproteins are associated with HDL which serves as the reservoir and which function, in part, to facilitate transfer of some apolipoproteins to VLDL and chylomicrons. Humans express 21 genes that are functionally classified as apolipoproteins, several of which are covered in the following Table.

Table of the Major Apolipoprotein Classifications*

| Apoprotein | Gene Name and Structure | Lipoprotein Association | Function and Comments |

| apoA-I | APOA1: 11q23.3; four exons; four alternatively spliced mRNAs; two protein isoforms: 267 and 158 amino acid preproproteins | Chylomicrons, HDL | APOA1, APOA4, APOA5, and APOC3 genes are clustered at 11q23.3; major protein of HDL, binds ABCA1 on macrophages to facilitate cholesterol uptake by HDL, critical anti-oxidant protein of HDL, activates lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase, LCAT |

| apoA-II | APOA2: 1q23.3; four exons; 100 amino acid preproprotein | Chylomicrons, HDL | near exclusive to HDL, represents the second-most abundant protein in HDL, enhances hepatic lipase activity, extrahepatic expression as well as misfolding of proprotein contribute to senile amyloidosis |

| apoA-IV | APOA4: 11q23.3; four exons; 396 amino acid precursor protein | Chylomicrons, HDL | APOA4, APOA1, APOA5, and APOC3 genes are clustered at 11q23.3; present in triglyceride rich lipoproteins; synthesized in small intestine, synthesis activated by PYY, acts in central nervous system to inhibit food intake, the details of which are discussed in the Regulation of Feeding Behaviors page |

| apoA-V | APOA5: 11q23.3; four exons; two alternatively spliced mRNAs; both encode same 366 amino acid precursor protein | Chylomicrons, HDL, VLDL, but not LDL | APOA5, APOA1, APOA4, and APOC3 genes are clustered at 11q23.3; expression is restricted to the liver; likely protects the liver from lipid excess during the early period of liver regeneration; associates with heparin, heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG), and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored HDL binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1); activates lipoprotein lipase but only in association with GPIHBP1 and HSPG; protects LPL from inhibition by ANGPTL3/ANGPTL8 complexes; increases intracellular concentration of triglycerides in hepatocytes through interaction with lipid droplets; is taken up by adipocytes through interaction with the LDL receptor family member protein, LRP1; decreases triglyceride concentration in adipocytes by increasing lipolysis, in part via increased expression of uncoupling protein 1, UCP1 (also known as thermogenin); mutations in the APOA5 gene are associated with familial chylomicronemia syndrome, FCS |

| apoB-48 | APOB: 2p24.1; 29 exons; 2179 amino acid precursor due to RNA editing | Chylomicrons | exclusively found in chylomicrons, derived from APOB gene by RNA editing in intestinal epithelium; lacks the LDL receptor-binding domain of apoB-100; the designation of apoB-48 refers to the fact that this protein contains 48% of the full-length apoB-100 protein |

| apoB-100 | APOB: 2p24.1; 29 exons; 4563 amino acid precursor protein | VLDL, IDL, LDL | major protein of VLDL, IDL, and LDL, binds to LDL receptor; one of the longest known proteins in humans; the designation of apoB-100 refers to the fact that this protein contains 100% of the coding capacity of the APOB encoded mRNA |

| apoC-I | APOC1: 19q13.32; five exons; 83 amino acid precursor protein | Chylomicrons, HDL, VLDL, IDL | clustered with APOE, APOC4, and APOC2 genes on chromosome 19; expression exclusive to the liver and macrophages; may also activate LCAT |

| apoC-II | APOC2: 19q13.32; four exons; 101 amino acid precursor protein; mature protein is 79 amino acids | Chylomicrons, HDL, VLDL, IDL | clustered with APOE, APOC1, and APOC4 on chromosome 19; expression exclusive to the liver and macrophages; expression regulated by bile acid-mediated activation of the FXR family of nuclear receptors as well as by hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α (HNF4α) which is a master regulator of hepatocyte lipid metabolism; activates lipoprotein lipase; mutations in the APOC2 gene are associated with familial chylomicronemia syndrome, FCS |

| apoC-III | APOC3: 11q23.3; four exons; 99 amino acid precursor protein | Chylomicrons, HDL, VLDL, IDL | APOC3, APOA1, APOA4, and APOA5 genes are clustered at 11q23.3; predominantly expressed in liver and to a lessor extent in the intestines; hepatic expression is regulated by glucose through activation of ChREBP and HNF4α; hepatic expression is induced by saturated fatty acids via activation of PGC-1β; insulin and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) inhibit expression through inhibition of the FOXO1 transcription factor; inhibits lipoprotein lipase, endothelial lipase, and hepatic lipase; interferes with hepatic uptake and catabolism of apoB-containing lipoproteins; appears to enhance the catabolism of HDL particles; enhances monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells; activates inflammatory signaling pathways |

| apoC-IV | APOC4: 19q13.32; four exons; 127 amino acid precursor protein | Chylomicrons, HDL, VLDL, IDL | clustered with APOE, APOC1, and APOC2 gene on chromosome 19; expression exclusive to the liver and macrophages; precise function is yet to be elucidated |

| apoD | APOD: 3q29; five exons; 189 amino acid precursor | HDL | produced by numerous tissues with highest levels in the testes and brain; closely associated with LCAT; amino acid homology to α2-microglobulin super family of proteins that are also known as the lipocalins; elevated levels in the brain associated with Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases |

| cholesterol ester transfer protein, CETP | CETP: 16q13; 17 exons; two alternatively spliced mRNAs; two protein isoforms: 493 and 433 amino acid precursor proteins | HDL | not considered a apolipoprotein although it is associated with HDL; plasma glycoprotein secreted primarily from the liver and is associated with cholesteryl ester transfer from HDL to LDL and VLDL in exchange for triglycerides |

| apoE | APOE: 19q13.32; six exons; five alternatively spliced mRNAs, four of which have alternate 5′-terminal exons compared to the longest protein coding mRNA | Chylomicron remnants, HDL, VLDL, IDL | clustered with APOC1, APOC2, and APOC4 genes on chromosome 19; expression exclusive to liver and macrophages; at least 3 alleles E2, E3, E4; the apoE2 allele has Cys at amino acids 112(TGC) and 158(TGC); apoE3 has Cys(TGC) and Arg(CGC) at these two positions, respectively; apoE4 has Arg(both codons CGC) at both positions; binds to LDL receptor; the apoE3 allele is the most common; apoE4 allele amplification associated with an inherited form of late-onset Alzheimer disease |

| apoF | APOF: 12q13.3; two exons; 326 amino acid precursor protein | primarily HDL, some LDL | initially called lipid transfer inhibitor protein (LITP) due to its ability to inhibit the activity of CETP; accelerates cholesterol clearance from the blood |

| apoH | APOH: 17q24.2; eight exons; 345 amino acid precursor protein | negatively charged surfaces | was originally identified as β2-glycoprotein 1; binds to phospholipids, primarily cardiolipins; inhibits serotonin release from platelets; alters ADP-mediated platelet aggregation |

| apoO | APOO: Xp22.11; 11 exons; 198 amino acid precursor protein | primarily HDL; also intracellular | expression is increased in heart of obese individuals; in addition to being secreted it is associated with mitochondria where it promotes mitochondrial uncoupling and enhancement of fatty acid oxidation; only apolipoprotein to have a chondroitin sulfate glycosylation |

| apoM | APOM: 6p21.33; seven exons; two alternatively spliced mRNAs; 188 and 116 amino acid proteins | nearly exclusive to HDL; only very small amounts in VLDL, LDL, and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins | exclusively expressed in liver and kidneys; membrane-bound; involved in lipid transport; exhibits antioxidant and anti-atherosclerotic activity through cholesterol efflux from cells; plasma form only from liver |

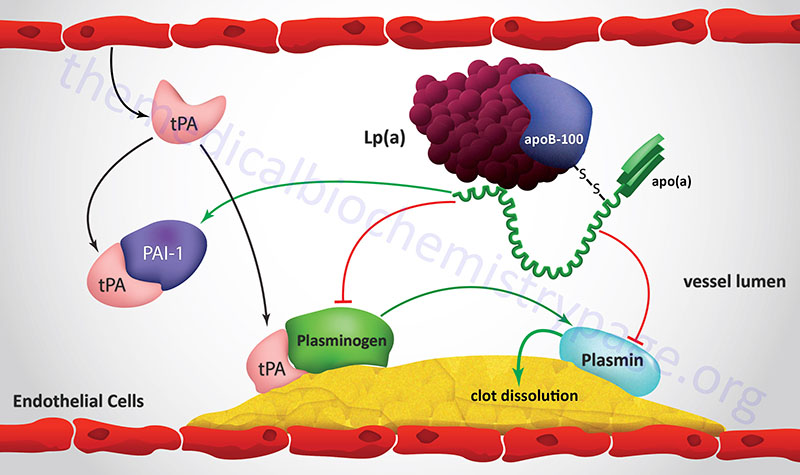

| apo(a) | LPA: 6q25.3-q26; 39 exons; the 2040 amino acid precursor represents the reference genome sequence | LDL | protein ranges in size from 300,000–800,000 as a result of from 2–43 copies of the Kringle-type domain; Kringle domains contain around 80 amino acids which form the domain via three intrachain disulfide bonds; disulfide bonded to apoB-100, forms a complex with LDL identified as lipoprotein(a), Lp(a); functions as a serine protease that inhibits tissue-type plasminogen activator 1 (tPA); strongly resembles plasminogen; may deliver cholesterol to sites of vascular injury, high risk association with premature coronary artery disease and stroke |

*apoC-IV and apoL1-apoL5 not included; apoJ not included as it is not an apolipoprotein but actually the chaperone clusterin

Apolipoprotein B

Chylomicrons and VLDL contain one molecule each of the protein (apoB) derived from the APOB gene. The apoB protein in chylomicrons is different from that found in VLDL as a result of editing of the primary APOB derived mRNA within intestinal enterocytes. Editing of the APOB mRNA changes a CAA codon (at amino acid 2180) to a UAA translational stop codon leading to premature termination of protein synthesis and the generation of a smaller protein called apoB-48 due to the fact that it comprises 48% of the possible coding capacity of the full-length apoB mRNA. This apolipoprotein (apoB-48) is found exclusively associated with chylomicrons.

When the APOB gene is transcribed within hepatocytes the mRNA is not edited and a full-length apoB protein is generated called apoB-100. This apolipoprotein (apoB-100) is found exclusively with the VLDL particles produced and secreted by the liver.

The C-to-U editing of the APOB mRNA requires a single-stranded RNA template with well defined characteristics in the immediate vicinity of the edited base, as well as protein cofactors that assemble into a functional complex referred to as a holoenzyme or editosome. This functional complex includes a minimal core composed of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide 1 (APOBEC-1; the catalytic deaminase) and a competence factor, APOBEC-1 complementation factor (A1CF). The function of A1CF is to act as an adaptor protein by binding both the APOBEC-1 enzyme and the mRNA substrate.

The APOBEC-1 protein is encoded by the APOBEC1 gene. The APOBEC1 gene is located on chromosome 12p13.31 and is composed of 6 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode two protein isoforms, the 236 amino acid isoform a and the 191 amino acid isoform b. Expression of the APOBEC1 gene is exclusive to the gastrointestinal system with the highest levels of expression in the duodenum.

Lipoprotein Lipase, LPL

In the capillaries of adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and the heart, the fatty acids of chylomicrons and VLDL/IDL/LDL are removed from the triglycerides by the action of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), which is found on the surface of the endothelial cells of the capillaries.

Lipoprotein lipase is encoded by the LPL gene. The LPL gene is located on chromosome 8p21.3 and is composed of 10 exons that encode a 475 amino acid precursor protein.

Synthesis of LPL occurs on the rough ER within parenchymal cells of adipose tissue (adipocytes) and of cardiac and skeletal muscle (cardiomyocytes and myocytes, respectively). As LPL is being synthesized, the activity of lipase maturation factor 1 (LMF1) is required for maturation of LPL and its migration through the secretory pathway. Mutations in the LMF1 gene result in a form of familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS). Lipase maturation factor 1 is also responsible for the maturation of hepatic lipase (encoded by LIPC gene) and endothelial lipase (encoded by the LIPG gene).

The significance of LMF1 in overall blood lipid homeostasis was demonstrated when a mutation in the gene was identified in mice. Mice homozygous for the mutation died shortly after birth with massive hypertriglyceridemia. These mice exhibited essentially no LPL nor hepatic lipase activity. In 2007 a nonsense mutation in the LMF1 gene was identified in a patient suffering from severe hypertriglyceridemia, repeated episodes of pancreatitis, tuberous xanthomas, and acquired partial lipodystrophy in conjunction with type 2 diabetes. This mutation was at tyrosine 439 and is identified as Y439X. Subsequent to the identification of the Y439X mutation an additional nonsense mutation was found in the tryptophan codon at position 464 (W464X).

LPL is then subsequently exocytosed from the parenchymal cell where it binds to heparin sulfated proteoglycans (HSPG) present on the surface of the cell facing the subendothelial spaces. The enzyme is then picked up and transported from the subendothelial spaces of the capillaries to the capillary endothelial cells via the action of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored HDL binding protein 1 which is encoded by the GPIHBP1 gene.

The GPIHBP1 gene is located on chromosome 8q24.3 and is composed of 4 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode distinct protein isoforms. Mutations in the GPIHBP1 gene result in a form of familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) that was originally identified as hyperlipoproteinemia type 1D.

Functional LPL is a homodimer which remains associated with the apical (lumen) surface of the endothelial cells through its interactions with GPIHBP1. The role of the angiopoietin-like proteins in the processing of LPL are detailed below.

The apoC-II and apoA-V in the chylomicrons and VLDL activates LPL in the presence of phospholipid. In addition to apoC-II and apoA-V, several angiopoietin-like proteins (discussed in the next section) are critical to the regulation of LPL activity.

The free fatty acids released by the action of LPL are then absorbed by the tissues and the glycerol backbone of the triglycerides is returned, via the blood, to the liver and kidneys. Within the liver the glycerol is phosphorylated by glycerol kinase. The resultant glycerol-3-phosphate is then converted to the glycolytic intermediate, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), via the action of cytosolic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD1), and is utilized for glucose synthesis via the gluconeogenesis pathway.

During the removal of fatty acids, a substantial portion of phospholipid, apoA-V and apoC-II is transferred to HDL. The loss of apoC-II and apoA-V prevents LPL from further degrading the chylomicron remnants.

Angiopoietin-Like Proteins and Regulation of LPL Activity

As described in the previous section, lipoprotein lipase (LPL) is a rate-limiting enzyme for the removal of fatty acids present in the triglycerides in circulating lipoproteins, particularly chylomicrons. The major sites of LPL activity are the endothelial cells of the capillaries of the heart, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Given that the heart and skeletal muscle depend on fatty acid oxidation for energy production, it is not surprising that these tissues abundantly express this enzyme. Since adipose tissue is the major site of fatty acid storage, through fatty acid esterification into triglycerides, LPL is abundantly expressed in white adipose tissue (WAT) as well. High levels of LPL in adipose tissue allows adipocytes access to the fatty acids in circulating triglycerides.

Although found tethered to the apical (luminal) membranes of capillary endothelial cells, the endothelial cells themselves do not synthesize the enzyme. LPL is synthesized in the parenchymal cells of adipose tissue, heart muscle and skeletal muscle and is secreted into the subendothelial spaces. Endothelial cell surface GPIHBP1 then picks up LPL and transfers it from the basolateral side of the endothelial cell to the apical side. In the lumen of the capillaries LPL remains tethered to GPIHBP1 as a functional homodimer.

Because LPL plays such a central role in triglyceride metabolism specifically, and in the regulation of overall lipoprotein metabolism in general, its activity is carefully regulated in a tissue-specific manner in relation to the daily feed-fast cycles. Following the intake of food, the level of LPL in WAT is increased whereas its levels in heart and skeletal muscle declines. Conversely, during periods of fasting LPL activity in WAT declines, whereas in heart and skeletal muscle LPL levels rise. These rapid changes in LPL activity are determined by post-translational mechanisms that involve interactions with proteins of the angiopoietin-like protein family as well as with apolipoproteins in the circulating chylomicrons and VLDL. The predominant lipoprotein-associated regulator of LPL activity is apoC-II (apoC-2) which chylomicrons and VLDL acquire from HDL. Another minor apolipoprotein that can activate LPL is apoA-V (apoA-5).

The activity of LPL is also regulated by proteins of the angiopoietin-like protein (ANGPTL) family. Humans express eight angiopoietin-like protein encoding genes identified as ANGPTL1–ANGPTL8. The angiopoietin-like proteins share structural, but not functional, similarity to angiopoietins which are members of the vascular endothelial growth factor family. Humans express four angiopoietin family member proteins (ANGPT1–ANGPT4) that exert their effects by binding to two related receptors called tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 1 (TIE1) and TIE2. The angiopoietin-like proteins do not bind to these receptors. Three of the angiopoietin-like proteins (ANGPTL3, ANGPTL4, and ANGPTL8) play crucial roles in the post-translational regulation of LPL activity.

ANGPTL3

Angiopoietin-like protein 3 (also known as angiopoietin 5) is produced exclusively by the liver and secreted into the circulation. Prior to its release from hepatocytes, a portion of the ANGPTL3 proprotein is cleaved into N-terminal and C-terminal fragments via the action of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type (PCSK) family member enzyme, furin (encoded by the FURIN gene). Furin is also known as PCSK3.

Both full-length and the cleaved fragments of ANGPTL3 are secreted into the circulation. The N-terminal portion of ANGPTL3 is involved in the regulation of overall lipoprotein metabolism through its ability to inhibit the activity of LPL, as well as to inhibit the activity of endothelial lipase, EL. Endothelial lipase is so-called because it is expressed exclusively by endothelial cells. Endothelial lipase functions almost exclusively as a phospholipase with highest affinity for HDL. The C-terminal fragment of ANGPTL3 is involved in angiogenesis.

The LPL inhibitory activity of ANGPTL3 on its own is minimal but is greatly enhanced upon its interaction with ANGPTL8.

The ANGPTL3 gene is located on chromosome 1p31.3 and is composed of 7 exons that encode a preproprotein of 460 amino acids. Expression of the ANGPTL3 gene is restricted to the liver and kidney. Mutation in the ANGPTL3 gene are the cause of familial combined hypolipidemia which is associated with reduced circulating levels of VLDL, LDL, and HDL due to increased activities of both LPL and endothelial lipase.

ANGPTL4

The ANGPTL4 gene was initially identified as a gene induced during periods of fasting and also as a result of its induction by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) in white adipose tissue (WAT). As a result of the observation of its induction during fasting, ANGPTL4 was originally called fasting-induced adipose factor (FIAF). Conversely, food intake results in reduced expression of ANGPTL4.

Like the ANGPTL3 proprotein, the ANGPTL4 proprotein is cleaved by furin and it is the N-terminal domain that is the potent LPL inhibitor. ANGPTL4 inhibits LPL activity by preventing the active homodimeric form of LPL from forming and by reducing the affinity of the monomers for binding to GPIHBP1 on the surface of capillary endothelial cells. In addition, ANGPTL4 promotes intracellular furin-mediated cleavage and inactivation of LPL.

Inhibition of adipose tissue LPL by ANGPTL4 during fasting is critical to the ensuring the delivery of fatty acids to cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle from circulating lipoproteins. Unlike ANGPTL3, ANGPTL4 is a potent LPL inhibitor in the absence of ANGPTL8. Interaction of ANGPTL4 with ANGPTL8 in WAT results in marked reduction in its ability to inhibit LPL.

The ANGPTL4 gene is located on chromosome 19p13.2 and is composed of 7 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode distinct protein isoforms. Expression of the ANGPTL4 gene is ubiquitous with the highest levels of expression being in the liver and adipose tissue.

ANGPTL8

Expression of the ANGPTL8 gene is enhanced in both the liver and white adipose tissue (WAT) in response to food intake, while fasting results in reduced levels of expression. Expression of ANGPTL8 is also induced in brown adipose tissue (BAT) in response to prolonged exposure to cold. Although the ANGPTL8 protein possesses sequence homology to both ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL4, it lacks the C-terminal fibrinogen-like domain that is present in both the ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL4 proteins.

ANGPTL8 forms complexes with both ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL4. ANGPTL8 functions in an endocrine manner with ANGPTL3 in the heart and skeletal muscle following food intake. The ANGPTL8-mediated activation of ANGPTL3 in these two tissues following feeding allows more fatty acids from circulating chylomicrons to be taken up by adipose tissue. Conversely, ANGPTL8 inhibits the activity of ANGPTL4 which normally inhibits LPL, thus resulting in increased LPL activity.

Loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in the ANGPTL8 gene have been identified and are associated with decreased levels of circulating triglycerides, decreased circulating levels of LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C), and increased circulating levels of HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C). These observations clearly point to a critical role for ANGPTL8 in the overall regulation of lipid metabolism.

Through differences in tissue expression and feed-fast cycle regulation of both ANGPTL4 and ANGPTL8, thereby resulting in regulation of ANGPTL3 activity, the activity of LPL is tightly controlled. During periods of feeding LPL activity is highest in adipose tissue and lowest in heart and skeletal muscle and during fasting LPL activity is highest in heart and skeletal muscle and lowest in adipose tissue.

The ANGPTL8 gene is also located on chromosome 19p13.2 and is composed of 4 exons that encode a precursor protein of 198 amino acids. Expression of the ANGPTL8 gene is restricted to liver and adipose tissue.

Role of CREBH in the Regulation of LPL Activity

The major transcription factor regulating the expression of the LPL gene in the liver is cAMP response element-binding protein, hepatocyte specific, CREBH. CREBH is critically involved in overall hepatic lipid homeostasis, particularly during periods of fasting and stress, such that there is increased triglyceride breakdown and fatty acid oxidation.

The gene encoding CREBH is CREB3L3 (cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 3). Expression of the CREB3L3 gene is restricted to the liver and the intestines.

The CREBH protein is localized the to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) which regulates its overall activity. When the CREBH protein is proteolyzed the N-terminal fragment is released and migrates to the nucleus where it functions as a transcription factor. With respect to the regulation of overall LPL activity, CREBH activates the expression of both the APOC2 (encoding apoC-II) and APOA5 (encoding apoA-V) genes allowing for increased LPL activity. ApoC-II directly activates LPL whereas apoA-V inhibits the ANGPTL3/ANGPTL8 complex that inhibits LPL activity.

In addition, following proteolytic activation the C-terminal fragment of CREBH functions as a hepatokine by being released. Following its release the C-terminal fragment interacts with ANGPTL3/ANGPTL8 complexes resulting in the blocking of the ability of these complexes to inhibit LPL activity.

Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein: MTP

Apolipoproteins generated from the APOB gene are large hydrophobic proteins that exists in plasma as apoB-48 or apoB-100 that, as outlined in Apolipoprotein B section above, are associated with intestinally derived chylomicrons or the liver derived VLDL, respectively.

Newly synthesized apoB containing lipoproteins, referred to as ‘nascent’ particles, undergo apolipoprotein exchange and enzymatic lipolysis as soon as they reach the lymph or the plasma. The incorporation of apoB-48 into chylomicrons, and of apoB-100 into VLDL, requires the activity of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone identified as microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP; also identified as MTTP) which is encoded by the MTTP gene.

The MTTP gene is located on chromosome 4q23 and is composed of 19 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode two precursor proteins of 894 amino acids (isoform 1) and 921 amino acids (isoform 2). Expression of the MTTP gene is essentially exclusive to the liver and the small intestines with very low level of expression seen in the kidney and testes.

There are three essential functions associated with MTP including lipid transfer, apoB binding, and membrane association. Functional MTP is composed of a large catalytic α-subunit encoded by the MTTP gene and a small β-subunit which is a member of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family of proteins that are involved in the processes of protein folding in the ER. The PDI family member gene that encodes the MTP β-subunit is P4HB (prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunit beta) and is also known as PDIA1.

Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein functions in the assembly and secretion of primordial apoB-containing lipoproteins in a process that includes two major steps. In the first step, the so-called primordial lipoprotein particle is synthesized while in the second step there is core expansion of the primordial lipoproteins and the synthesis of what is referred to as nascent lipoproteins.

The first step of primordial lipoprotein assembly involves both a nucleation and a desorption. When the newly synthesized apoB protein is translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum, the N-terminus of the protein associates with the inner membrane and acquires neutral lipids forming nucleation sites. These nucleation sites most likely arise from endoplasmic reticulum microdomains harboring triglyceride-synthesizing enzymes. The formation of these nucleation sites is enhanced in the presence of MTP due to its neutral lipid transfer activity.

In addition to its effect on the composition of ER membrane lipids, MTP can also transfer triglycerides to nascent apoB proteins either during or following their translation. The phospholipid transfer activity of MTP is critical for desorption of primordial apoB particles along with neutral lipids from the ER-associated nucleation sites. This latter process renders the apoB containing particles able to be secreted.

A form of abetalipoproteinemia is associated with mutations in the MTTP gene. Abetalipoproteinemia is characterized by fat malabsorption, steatorrhea, acanthocytosis (thorny looking cells), and hypocholesterolemia in infancy. Later in life, deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins is associated with development of atypical retinitis pigmentosa, coagulopathy, posterior column neuropathy, and myopathy.

Phospholipids of Lipoprotein Particles

Lipoprotein particles possess a monolayer of phospholipids that cover the surface of the particles. The major phospholipids of lipoprotein particles are phosphatidylcholines, PC. The majority of phospholipid synthesis occurs on the cytoplasmic surface of the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum, ER. Therefore, in order for their incorporation into lipoprotein particles, these phospholipids need to be shuttled across the membrane into the ER lumen.

Recent studies have demonstrated that two proteins that reside in the ER membrane likely serve as phospholipid scramblases to facilitate phospholipid transfer into the ER lumen. These proteins are encoded by the TMEM41B (transmembrane protein 41B) and VMP1 (vacuole membrane protein 1) genes. Prior experiments demonstrated that the TMEM41B encoded protein functions in intracellular lipid transport and in the assembly of autophagosomes. The VMP1 protein is also involved in autophagosome biogenesis.

The phospholipid transfer protein (encoded by the PLTP gene) that is involved in the transfer of phospholipids from the two triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL), chylomicrons and VLDL, to circulating HDL particles is also involved in the overall process of phospholipid incorporation into lipoproteins.

Another important enzyme involved in overall lipoprotein maturation related to phospholipid incorporation is the lysophospholipid acyltranstransferase (LPLAT) family member, LPLAT12 which is encoded by the LPCAT3 gene. LPLAT12 also belongs to the membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing (MBOAT) family and as such is identified as MBOAT5. Expression of the LPCAT3 gene is highest in the intestines and the liver, as would be expected from a gene encoding a protein playing an important role in lipoprotein particle assembly.

Chylomicrons

Chylomicrons are assembled in intestinal enterocyte as a means to transport dietary fatty acids and cholesterol to the rest of the body. Following the digestion of dietary triglycerides and phospholipids into free fatty acids, monoglycerides, and lysophosphatidic acids and the uptake of these molecules into intestinal enterocytes, triglycerides and phospholipids are re-synthesized and free cholesterol is esterified. These lipids are then packaged into the lipoprotein particles termed chylomicrons. Chylomicrons are, therefore, the molecules formed to mobilize dietary (exogenous) lipids. The predominant lipids of chylomicrons are triglycerides (see Table above). The apolipoproteins that predominate before the chylomicrons enter the circulation include apoB-48, apoA-I, apoA-II, and apoA-IV.

ApoB-48 combines only with chylomicrons. ApoB-48 incorporation into forming chylomicrons involves the function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) associated heterodimeric complex called microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, MTTP (also identified as MTP). Chylomicrons leave the intestine via the lymphatic system and enter the circulation at the left subclavian vein. In the bloodstream, chylomicrons acquire apoC-II and apoE from plasma HDL.

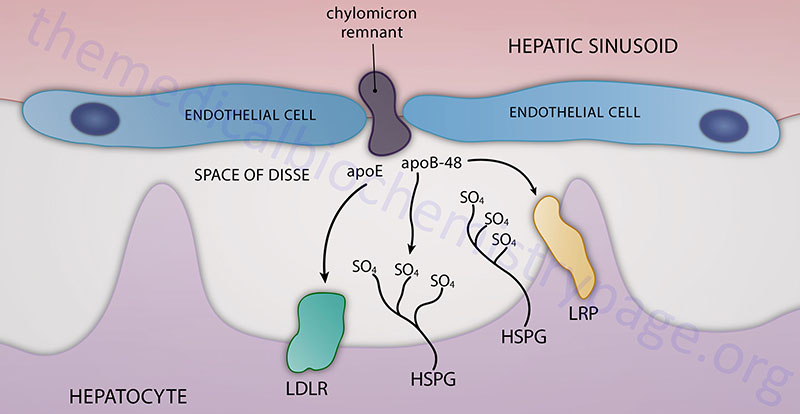

Hepatic Chylomicron Remnant Uptake

Chylomicron remnants, containing primarily cholesteryl esters, apoE, and apoB-48, are then delivered to, and taken up by, the liver. The remnant particle must be of a sufficiently small size such that can pass through the fenestrated endothelial cells lining the hepatic sinusoids and enter into the space of Disse. Chylomicron remnants can then be taken up by hepatocytes via interaction with the LDL receptor which is facilitated by the presence of apoE. In addition, while in the space of Disse chylomicron remnants can accumulate additional apoE that is secreted free into the space. This latter process allows the remnant to be taken up via the chylomicron remnant receptor, which is a member of the LDL receptor-related protein (LRP) family. The recognition of chylomicron remnants by the hepatic remnant receptor also requires apoE. Chylomicron remnants can also remain sequestered in the space of Disse by binding of apoE to heparan sulfate proteoglycans and/or binding of apoB-48 to hepatic lipase. While sequestered, chylomicron remnants may be further metabolized which increases apoE and lysophospholipid content allowing for transfer to LDL receptors or LRP for hepatic uptake.

VLDL, IDL, and LDL

The dietary intake of both fat and carbohydrate, in excess of the needs of the body, leads to the conversion, in the liver, of the excess carbons into fatty acids which are then incorporated into triglycerides. These triglycerides are packaged into VLDL and released into the circulation for delivery to the various tissues (primarily muscle and adipose tissue) for storage or production of energy through oxidation. VLDL are, therefore, the molecules formed to transport endogenously derived triglycerides to extra-hepatic tissues. A critical contributor to the hepatic synthesis of VLDL is phosphatidylcholine which is necessary for the packaging of triglycerides into VLDL.

In addition to triglycerides, VLDL contain some cholesterol and cholesteryl esters and the apoproteins, apoB-100 (a single copy). ApoB-100 incorporation into forming VLDL particles, similar to the incorporation of apoB-48 into chylomicrons, involves the function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) associated microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, MTTP. Upon secretion into the blood, VLDL accumulates apoC-I, apoC-II, apoC-III, and apoE from circulating HDL similarly to the incorporation of these apolipoproteins into nascent chylomicrons.

The fatty acid portion of VLDL is released to adipose tissue and muscle in the same way as for chylomicrons, through the action of lipoprotein lipase. The action of lipoprotein lipase coupled to a loss of certain apoproteins (e.g. apoC-II) converts VLDL to intermediate density lipoproteins (IDL), also termed VLDL remnants. IDL contain multiple copies of apoE and a single copy of apoB-100. The presence of the multiple copies of apoE enable these lipoprotein particles to have very high affinity for the LDL receptor on cells such as hepatocytes and adrenal cortex cells. Conversion of VLDL to IDL is also associated with loss of apoCs by transfer back to HDL. Further loss of fatty acids from triglycerides, as well as transfer of apoE back to HDL converts IDL to LDL. The presence of the apoB-100 protein allows LDL to be recognized by the LDL receptor but the lack of apoE makes the affinity much lower compared to that of IDL.

The liver takes up IDL and LDL after they have interacted with the LDL receptor to form a complex, which is then endocytosed by the cell. For LDL receptors in the liver to recognize IDL and LDL requires the presence of apoB-100 and is enhanced (in the case of IDL) by the presence of apoE. The LDL receptor is also sometimes referred to as the apoB-100/apoE receptor. The importance of apoE in cholesterol uptake by LDL receptors has been demonstrated in transgenic mice lacking functional apoE genes. These mice develop severe atherosclerotic lesions at 10 weeks of age even when fed a low-fat diet.

Of significance to overall serum total cholesterol levels is the fact that one of the events that results in the conversion of IDL to LDL is the loss of apoE which is returned to HDL. Although LDL particles still possess apoB-100 which is required for LDL receptor binding, the loss of apoE makes their affinity for the receptor reduced. Any perturbation in serum total cholesterol regulation will result in increased circulating LDL. The longer that LDL remains in the blood the greater the likelihood the protein and lipid components will become oxidized (forming oxLDL). The significance of oxLDL is that these particles are bound to the oxLDL receptors, primarily on macrophages, leading to enhanced intravascular inflammation. The significances of increased serum oxLDL is discussed below in the section on lipoprotein receptors, specifically the scavenger receptors.

The cellular requirement for cholesterol as a membrane component is satisfied in one of two ways: either it is synthesized de novo within the cell, or it is supplied from extra-cellular sources, namely, chylomicrons and IDL/LDL. As indicated above, the dietary cholesterol that goes into chylomicrons is supplied to the liver by the interaction of chylomicron remnants with the remnant receptor. In addition, cholesterol synthesized by the liver can be transported to extra-hepatic tissues if packaged in VLDL. In the circulation VLDL are converted to IDL and LDL through the action of lipoprotein lipase. IDL and LDL are the primary plasma carriers of cholesterol for delivery to all tissues via their LDL receptor mediated uptake.

The exclusive apolipoprotein of LDL is apoB-100. LDL are taken up by cells via LDL receptor-mediated endocytosis, as described above for IDL uptake. The uptake of LDL occurs predominantly in liver (75%), adrenals and adipose tissue. As with IDL, the interaction of LDL with LDL receptors requires the presence of apoB-100. The endocytosed membrane vesicles (endosomes) fuse with lysosomes, in which the apoproteins are degraded and the cholesterol esters are hydrolyzed to yield free cholesterol. The cholesterol is then incorporated into the plasma membranes as necessary.

Excess intracellular cholesterol is re-esterified, by sterol O-acyltransferase 2 (SOAT2), for intracellular storage. The activity of SOAT2 is enhanced by the presence of intracellular cholesterol. The original name given to SOAT2 was acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase 2 (ACAT2). This designation conflicts with that for the official ACAT2 enzyme (a member of thiolase family of enzymes), acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2.

The SOAT2 gene is located on chromosome 12q13.13 and is composed of 16 exons that encode a 522 amino acid protein.

Another SOAT gene, SOAT1, encodes a protein that is also involved in the regulation of intracellular cholesterol concentrations. The SOAT1 gene is located on chromosome 1q25 and is composed of 17 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs.

Insulin and triiodothyronine (T3) increase the binding of LDL to liver cells, whereas glucocorticoids (e.g., dexamethasone) have the opposite effect. The precise mechanism for these effects is unclear but may be mediated through the regulation of apoB degradation. The effects of insulin and T3 on hepatic LDL binding may explain the hypercholesterolemia and increased risk of atherosclerosis that have been shown to be associated with uncontrolled diabetes or hypothyroidism.

The consumption of alcohol is associated with either a protective or a negative effect on the level of circulating LDL. Low level alcohol consumption, particularly red wines which contain the antioxidant resveratrol, appear to be beneficial with respect to cardiovascular health. Resveratrol consumption is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease. One major effect of resveratrol in the blood is the prevention of oxidation of LDL, (forming oxLDL). Oxidized LDL contribute significantly to the development of atherosclerosis. Conversely excess alcohol consumption is associated with the development of fatty liver which in turn impairs the ability of the liver to take up LDL via the LDL receptor resulting in increased LDL in the circulation. Clearly a reduction in alcohol consumption will have a significant impact on overall cardiovascular and hepatic function.

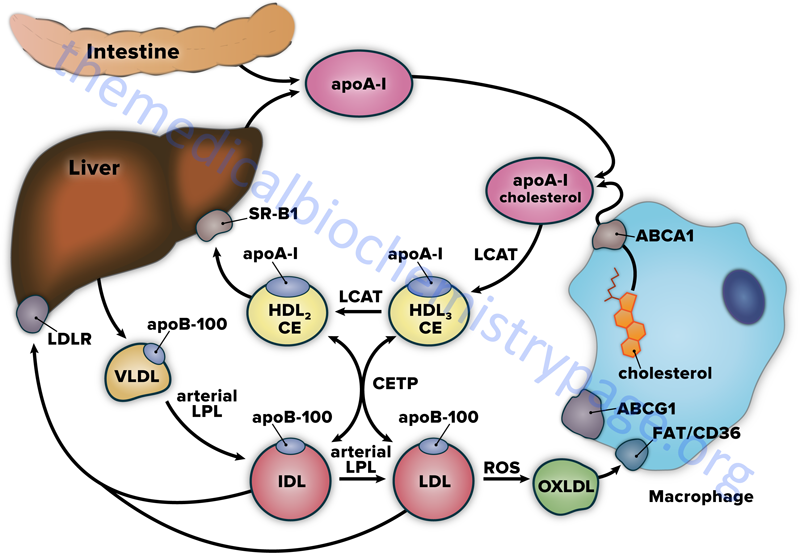

High Density Lipoproteins, HDL

HDL represent a heterogeneous population of lipoproteins in that they exist as functionally distinct particles possessing different sizes, protein content, and lipid composition. One of the major functions of HDL is to acquire cholesterol from peripheral tissues and transport this cholesterol back to the liver where it can ultimately be excreted following conversion to bile acids. This function is referred to as reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). The role of HDL in RCT represents the major atheroprotective (prevention of the development of atherosclerotic lesions in the vasculature) function of this class of lipoprotein. In addition to RCT, HDL exert anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and vasodilatory effects that together represent additional atheroprotective functions of HDL. Evidence has also been generated that demonstrates that HDL possess anti-apoptotic, anti-thrombotic, and anti-infectious properties. With respect to these various atheroprotective functions of HDL, it is the small dense particles (referred to as HDL3) that are the most beneficial.

HDL begin as the single protein, apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), which is synthesized de novo in the liver and small intestine. These newly formed HDL are devoid of any cholesterol, cholesteryl esters, lipids, and any other proteins. ApoA-I, as well as more complex HDL containing apoA-I, acquire cholesterol as described in the following paragraphs and outlined in the Figure below. As apoA-I picks up cholesterol, the resultant nascent HDL particle begins to accumulate numerous proteins from the blood. The primary apolipoproteins of HDL are apoA-I, apoC-I, apoC-II, apoD, apoE, apoF, apoM, and apoO. In fact, a major function of HDL is to act as a circulating store of apoC-I, apoC-II, and apoE. ApoA-I is the most abundant protein in HDL constituting over 70% of the total protein mass. In addition to apolipoproteins, HDL carry numerous enzymes that participate in the anti-oxidant activities of HDL.

Proteomics studies have demonstrated that as many as 300 different proteins can be found associated with HDL, many of which have no known role in lipid transport. Some of the critical enzymes in HDL include glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx), paraoxonase 1 (PON1), and platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH, also called lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, Lp-PLA2). Two additional functionally important enzymes found associated with HDL are lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) and cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP). Another important HDL component is the compound sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P; details of S1P activities can be found in the Sphingolipid Metabolism and the Ceramides page).

The primary mechanism by which HDL acquire peripheral tissue cholesterol is via an interaction with monocyte-derived macrophages in the subendothelial spaces of the tissues. Macrophages bind nascent HDL, that contain primarily apoA-I, through interaction with the ATP-binding cassette transport protein A1 (ABCA1). The transfer of cholesterol from macrophages, via the action of ABCA1, involves apoA-I and results in the formation of nascent discoidal lipoprotein particles termed pre-β HDL. The free cholesterol transferred in this way is esterified by HDL-associated LCAT.

LCAT is synthesized in the liver and so named because it transfers a fatty acid from the C-2 position of a lecithin (phosphatidylcholine, PC) to the C3-OH of cholesterol, generating a cholesteryl ester and a lysolecithin. The activity of LCAT requires interaction with apoA-I, which remains on the surface of HDL as they get larger through protein, cholesterol, and triglyceride acquisition. The cholesteryl esters formed via LCAT activity are internalized into the hydrophobic core of the pre-β HDL particle. As pre-β HDL particles progressively take up cholesterol and proteins they become larger and spherical generating the mature HDL particles.

The importance of ABCA1 in reverse cholesterol transport is evident in individuals harboring defects in ABCA1 gene. These individuals suffer from a disorder called Tangier disease which is characterized by two clinical hallmarks; enlarged lipid-laden tonsils and low serum HDL.

HDL also acquire cholesterol by extracting it from cell surface membranes. This process has the effect of lowering the level of intracellular cholesterol, since the cholesterol stored within cells as cholesteryl esters will be mobilized to replace the cholesterol removed from the plasma membrane. The transfer of cholesterol from peripheral tissue cells to HDL in this way involves the action of the ATP-binding cassette protein G1 (ABCG1). Approximately 20% of HDL uptake of peripheral tissue cholesterol occurs via the ABCG1-mediated pathway.

Cholesterol-rich HDL return to the liver, where they bind to a receptor that is a member of the scavenger receptor family, specifically the scavenger receptor BI: SR-BI (see below). When HDL binds to SR-BI it is not internalized as is the case for IDL or LDL following their binding to the LDL receptor. Following HDL binding to SR-BI the cholesteryl esters are taken up by the hepatocytes through caveolae while the HDL and SR-BI remain on the plasma membrane. Caveolae (Latin for little caves) are specialized “lipid rafts” present in flask-shaped indentations in the plasma membranes of many cells types that perform a number of signaling functions.

HDL particles exhibit complex, and sometimes contradictory rolls in vascular biology. Depending upon the vascular context, as well as the make-up of HDL particle, these lipoproteins can serve antiatherogenic or proatherogenic functions. In the absence of systemic inflammation many of the enzymes and apolipoproteins associated with HDL play important roles in reducing the amount of oxidized lipid to which peripheral tissues are exposed. Some of these important proteins are apoA-I, PON1, GPx (an important anti-oxidant enzyme), and PAF-AH (see section below for the discussion of this important activity). However, when an individual has an ongoing systemic inflammatory state, these anti-oxidant proteins can be dissociated from the HDL or become inactivated resulting in the increased generation of oxidized and peroxidized lipids which are proatherogenic. Atherosclerotic plaques also produce myeloperoxidase which chemically modifies HDL-associated apoA-I rendering it less capable of interacting with cell surfaces such as macrophages. This latter effect results in a reduced capacity for removal of cholesterol from lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) leaving the foam cells in a more pro-inflammatory state.

Reverse cholesterol transport can also involve the transfer of cholesterol esters from HDL to VLDL, IDL, and LDL. This transfer requires the activity of the plasma glycoprotein cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP). The transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL via CETP activity also involves an exchange of triglycerides to the HDL. This action of HDL associated CETP has the added effect of allowing the excess cellular cholesterol to be returned to the liver through the LDL receptor. However, some of the LDL is oxidized in the periphery (generating oxLDL) where it can participate in atherogenesis.

Additionally, when HDL particles become enriched with triglycerides they are better targets for the action of hepatic lipase. As hepatic lipase acts on the triglyceride-rich HDL they become progressively smaller and unstable which results in the release of apoA-I. The loss of apoA-I renders the HDL particle unable to participate in reverse cholesterol transport. Blocking the activity of CETP keeps HDL particles less triglyceride-enriched while also reducing cholesterol transfer to VLDL, IDL, and LDL ultimately resulting in reduced circulating levels of proatherogenic oxLDL. This latter observation suggests that CETP inhibition may be a viable therapeutic approach for elevating the circulating levels of HDL. This is discussed below.

Anti-oxidant & Anti-inflammatory Activities of HDL

Using a range of both in vitro and in vivo assays it has been possible to quantify the anti- and pro-inflammatory properties, as well as the anti-oxidant functions of HDL. Cell-free assays have been used to measure the ability of HDL to prevent the formation of oxidized phospholipids in LDL as well as to determine the ability of HDL to degrade oxidized phospholipids that are already formed. In cell culture assays HDL have been shown to inhibit monocyte chemotaxis in response to oxidized LDL or to prevent the upregulation of cell adhesion molecules on endothelial cells. Both of these latter effects are strongly anti-inflammatory since monocytes need to migrate to a site of inflammation via a chemotactic gradient and then adhere to the endothelium at the site of injury or inflammatory event. The role of HDL in promoting cholesterol efflux from cells, especially from macrophages, (the process of reverse cholesterol transport) reduces the activation of inflammatory responses in these cells. The analysis of HDL functions in oxidative and inflammatory events has identified the role of various apolipoproteins associated with HDL in these processes which are outlined in the following sections.

Apolipoprotein A-I

Numerous lines of evidence demonstrate that apoA-I is a major anti-atherogenic and anti-oxidant factor in HDL due to its critical role in the HDL-mediated process of reverse cholesterol transport. In addition to reverse cholesterol transport, apoA-I can remove oxidized phospholipids from oxidized LDL (oxLDL) and from cells. Specific methionine residues (Met112 and Met148) of apoA-I have been shown to directly reduce cholesterol ester hydroperoxides and phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides.

Apolipoprotein A-II

Experiments in transgenic mice have demonstrated that human apoA-II-enriched HDL served to protect VLDL from oxidation more efficiently than HDL from control animals. The human apoA-II-enriched HDL support highly effective reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages. Although there is a demonstrated benefit of apoA-II in reverse cholesterol transport and in reduced LDL oxidation, these transgenic mice exhibited increased displacement of PON1 and PAF-AH from HDL. The displacement of these two beneficial HDL-associated proteins (see below) likely explains the increased atherosclerosis seen in dyslipidemic mice that overexpress either human or murine apoA-II. However, recent clinical studies in human patients show that the higher the plasma apoA-II concentration the lower is the risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD).

Apolipoprotein A-IV

Apolipoprotein A-IV has multiple activities related to lipid and lipoprotein metabolism as well as the control of feeding behaviors. ApoA-IV participates in reverse cholesterol transport by promoting cholesterol efflux as well as through by activation of LCAT. ApoA-IV has also been shown to have anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic actions. ApoA-IV is secreted only by the small intestine in humans (although it is expressed in the hypothalamus) and its synthesis in the gut is stimulated by active lipid absorption. Intestinal apoA-IV synthesis is enhanced by protein tyrosine-tyrosine (PYY) secreted from the ileum. Intestinal apoA-IV, present in the circulation following ingestion of fat, as well as hypothalamic apoA-IV is an anorexigenic peptide which mediates, in part, the appetite suppressing effects of a lipid-rich meal.

Apolipoprotein E

The anti-atherosclerotic activity associated with apoE is well known. This beneficial effect of apoE is due primarily to its role in the process of receptor-mediated uptake of LDL by the liver. Although apoE-mediated hepatic uptake of LDL results in a reduction in hypercholesterolemia, apoE has also been shown to inhibit atherosclerosis without any significant effect on hypercholesterolemia. In addition, different apoE alleles have demonstrated activities. For example apoE2 stimulates endothelial nitric oxide (NO) release and has anti-inflammatory activities, whereas, apoE4 is pro-inflammatory.

Paroxonases 1 and 3

Paraoxonases are a family of enzymes that hydrolyze organophosphates. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) is synthesized in the liver and is carried in the serum by HDL. PON1 possesses anti-oxidant properties, in particular it prevents the oxidation of LDL. Evidence suggests that the direct anti-oxidant effect of HDL, on LDL oxidation, is mediated by PON1. PON1 has been shown to enhance cholesterol efflux from macrophages by promoting HDL binding mediated by ABCA1, which in turn results in a reduction of pro-inflammatory signaling. This anti-inflammatory action of PON1 serves an anti-atherosclerotic function of the protein. That PON1 is indeed important in preventing atherosclerosis has been demonstrated in mice deficient in the protein. Atherosclerotic lesions that develop in these mice when fed a high-fat diet are twice the size that develop in similarly fed control mice. In human clinical studies, a higher level of PON1 activity is associated with a lower incidence of major cardiovascular events. Other pathological conditions in humans that are associated with oxidative stress, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Alzheimer disease, are frequently associated with reduced activity of PON1.

PON3, which is another HDL-associated paraoxonase, has also been shown to prevent the oxidation of LDL. Transgenic mice expressing human PON3 have been shown to be protected from the development of atherosclerosis, without any significant changes in plasma lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride or glucose levels.

Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH)

There are two major forms of PAF-AH, cytosolic and plasma lipoprotein-associated. The plasma form of PAF-AH circulates bound to HDL. Given that PAF-AH is a member of the PLA2 family and that it also circulates bound to lipoprotein it is more commonly referred to as the lipoprotein-associated PLA2 (Lp-PLA2). Experimental data suggests that Lp-PLA2, rather than PON1, is the major HDL-associated hydrolase that is responsible for the hydrolysis of oxidized phospholipids. Lipoproteins that are isolated from transgenic mice expressing human Lp-PLA2 are more resistant to oxidative stress. In addition, these mice have been shown to have reduced levels of foam cell (lipid-rich macrophages) formation and enhanced rates of cholesterol efflux from macrophages. In experimental atherosclerosis models, gene transfer of LP-PLA2 inhibits atherosclerotic lesion formation in apoE-deficient mice. In humans, Lp-PLA2 deficiency is associated with increases in cardiovascular disease, while conversely circulating levels of Lp-PLA2 serve as an independent marker of the risk for developing coronary artery disease.

Glutathione Peroxidase 1

Glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1) functions primarily to reduce hydrogen peroxide to water, but it has been shown to also reduce lipid hydroperoxides to corresponding hydroxides effectively detoxifying these types of abnormally modified lipids. Numerous human clinical studies indicated that GPx1 provides a protective role against the development of atherosclerosis. These effects of GPx1 have also been shown in mice deficient in apoE where concomitant loss of the peroxidase results in increased rates of atherosclerotic plaque formation. The role of GPx1 in the protection from development of atherosclerosis is most pronounced under conditions of significant oxidative stress.

Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P)

S1P is a bioactive lysophospholipid involved in a number of physiologically important pathways. For more detailed information of S1P activities visit the Sphingolipid Metabolism and the Ceramides page as well as the Bioactive Lipids and Lipid Sensing Receptors page. Within the blood, HDL are known to be the most prominent carriers of S1P. Indeed, many of the biological effects of HDL are mediated, in part, via S1P binding to its cell surface receptors. Effects of HDL on endothelial cells, such as migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis, are mediated, in part, by S1P associated with HDL. HDL-associated S1P inhibits pro-inflammatory responses, such as the generation of reactive oxygen species, activation of NAD(P)H oxidase and the production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. While the HDL-associated forms of S1P exhibit these anti-inflammatory effects, free plasma S1P can activate inflammatory events dependent upon the receptor sub-type to which it binds.

Therapeutic Benefits of Elevating HDL

Numerous epidemiological and clinical studies over the past 10 years have demonstrated a direct correlation between the circulating levels of HDL cholesterol (most often abbreviated HDL-c) and a reduction in the potential for atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD). Individuals with levels of HDL above 50mg/dL are several time less likely to experience CHD than individuals with levels below 40mg/dL. In addition, clinical studies in which apoA-I, (the predominant protein component of HDL-c) or reconstituted HDL are infused into patients, raises circulating HDL levels and reduces the incidence of CHD. Thus, there is precedence for therapies aimed at raising HDL levels in the treatment and prevention of atherosclerosis and CHD. Unfortunately current therapies only modestly elevate HDL levels. Both the statins and the fibrates have only been shown to increase HDL levels between 5%–20% and niacin is poorly tolerated in many patients. Therefore, alternative strategies aimed at increasing HDL levels are being tested.

Cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) is plasma glycoprotein secreted primarily from the liver and plays a critical role in HDL metabolism by facilitating the exchange of cholesteryl esters (CE) from HDL for triglycerides (TG) in apoB containing lipoproteins, such as LDL and VLDL. The activity of CETP directly lowers the cholesterol levels of HDL and enhances HDL catabolism by providing HDL with the TG substrate of hepatic lipase. Thus, CETP plays a critical role in the regulation of circulating levels of HDL, LDL, and apoA-I. It has also been shown that in mice naturally lacking CETP most of their cholesterol is found in HDL and these mice are relatively resistant to atherosclerosis.

The potential for the therapeutic use of CETP inhibitors in humans was first suggested when it was discovered in 1985 that a small population of Japanese had an inborn error in the CETP gene leading to hyperalphalipoproteinemia and very high HDL levels. To date three CETP inhibitors have been used in clinical trials. These compounds are anacetrapib, torcetrapib, evacetrapib, and dalcetrapib. Although torcetrapib is a potent inhibitor of CETP, its’ use has been discontinued due to increased negative cardiovascular events and death rates in test subjects. Clinical trials with dalcetrapib resulted in increases in HDL (19–37%) and a modest decrease (≈6%) in LDL levels. Clinical trials with evacetrapib raised HDL by more 125% and lowered LDL by more than 30%. Clinical trials with anacetrapib resulted in a significant increase in HDL (≈130%) and lowered LDL (≈40%).

Although the outcomes of large clinical trials with CETP inhibitors have not yet led to approved therapies they have found that one potential impact of CETP inhibitors is on the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes. Regardless of the ultimate impact on cardiovascular events, administration of CETP inhibitors was found to be associated with a reduced rate of development of type 2 diabetes and also with improved plasma glucose control in test subjects who already had diabetes. Whereas the specific mechanism underlying these observations remains unclear, there is evidence that HDL exert favorable effects on pancreatic β-cell function.

As described in the section below on therapeutic intervention in hyperlipidemias/hypercholesterolemias, the fibrates (e.g. fenofibrate) are a class of drugs that has been shown to result in small increases in HDL levels. The fibrates function by activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) class of transcription co-activators. However, the level of HDL increase with the current PPARα agonists is minimal at best primarily due to lack of specificity for PPARα. Therefore, current research is focused on subtype-specific PPARα agonists that have increased potency. One compound currently being tested, GFT505, is a selective PPARα agonist with a potency 100-fold greater than fenofibrate.

The liver X receptors (LXRα and LXRβ) are transcription co-activators that are involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism and have also been associated with regulation of inflammation. LXR agonists have been shown to inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis in mouse models of the disorder. Although the precise mechanism by which these LXR agonists effect a reduction in the progression of atherosclerosis is not clear, it is known that the genes encoding ABCA1 and ABCG1 contain LXR-binding sites. In fact, LXR agonists up-regulate the expression of both ABCA1 and ABCG1 in macrophages which leads to increased reverse cholesterol transport. Less cholesterol in macrophages leads to a reduced inflammatory activity of the macrophage which in turn likely contributes to the reduced atherosclerosis.

However, there is a limitation to the utility of LXR agonists as shown by the first generation synthetic LXR ligands which activate both LXRs and lead to marked increases in hepatic lipogenesis and plasma triglyceride levels. These effects are due to the role of LXRs in activation of hepatic SREBP-1c and the resultant activation of each of its target genes as described above. Although it could be theoretically possible to enhance the reverse cholesterol effects of LXRs without targeting hepatic lipogenesis with the use of LXRβ-specific ligands since most of the hepatic responses are due to activation of LXRα, this will be a difficult challenge as the ligand binding pocket in both isoforms has been shown to be nearly identical. In addition, there are species-specific differences in overall LXR responses that need to be carefully considered meaning the use of animal models that more closely resemble humans in their metabolic pathways.

Lipoprotein Receptors

LDL Receptors

LDL are the principal plasma carriers of cholesterol delivering cholesterol from the liver (via hepatic synthesis of VLDL) to peripheral tissues, primarily the adrenals, the gonads, and adipose tissue. LDL also return cholesterol to the liver. The cellular uptake of cholesterol from both IDL and LDL occurs following the interaction of the lipoprotein particles with the LDL receptor (also called the apoB-100/apoE receptor). IDL possess both apoB-100 and apoE, where the presence of apoE enhances the binding of IDL to the LDL receptor. On the other hand, the sole apoprotein present in LDL is apoB-100, which is required for interaction with the LDL receptor, but the lack of apoE reduces the overall affinity of LDL for the LDL receptor.

The LDL receptor is encoded by the LDLR gene. The LDLR gene is located on chromosome 19p13.2 and is composed of 18 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs which encode six distinct isoforms of the LDL receptor. The longest LDL receptor isoform is a 860 amino acid precursor protein. The LDL receptor spans the plasma membrane and it is the extracellular domain that is responsible for apoB-100/apoE binding. The intracellular domain is responsible for the clustering of LDL receptors into regions of the plasma membrane termed coated pits. Associated with the extracellular domain of the LDL receptor is the enzyme called proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9).

Once LDL binds the receptor, the LDL-PCSK9-LDLR complexes are rapidly internalized (endocytosed). ATP-dependent proton pumps lower the pH in the endosomes, which results in dissociation of the LDL from the receptor. The portion of the endosomal membranes harboring the LDL receptor are then recycled to the plasma membrane and the LDL-containing endosomes fuse with lysosomes. However, within the endosome some of the LDL receptor protein is degraded via the action of PCSK9 resulting in less than 100% recycling of the LDL receptor to the plasma membrane. Acid hydrolases of the lysosomes degrade the apoproteins and release free fatty acids and cholesterol. As indicated above, the free cholesterol is either incorporated into plasma membranes or esterified (by SOAT2; formerly called ACAT) and stored within the cell.

The level of intracellular cholesterol is regulated through cholesterol-induced suppression of LDL receptor synthesis and cholesterol-induced inhibition of cholesterol synthesis. The increased level of intracellular cholesterol that results from LDL uptake has the additional effect of activating SOAT2, thereby allowing the storage of excess cholesterol within cells. However, the effect of cholesterol-induced suppression of LDL receptor synthesis is a decrease in the rate at which LDL and IDL are removed from the serum. This can lead to excess circulating levels of cholesterol and cholesteryl esters when the dietary intake of fat and cholesterol exceeds the needs of the body. The excess cholesterol tends to be deposited in the skin, tendons and (more gravely) within the arteries, leading to atherosclerosis.

LDL Receptor-Related Proteins (LRP)

The LDL receptor-related protein family represents a group of structurally related transmembrane proteins involved in a diverse range of biological activities including lipid metabolism, nutrient transport, protection against atherosclerosis, as well as numerous developmental processes. The LDL receptor (LDLR) described above represents the founding member of this family of proteins. The additional LRP include LRP1, LRP1B, LRP2 (also called megalin), LRP3, LRP4 (also called MEGF7 for multiple epidermal growth factor-like domains protein 7), LRP5 (also assigned the designation LRP7), LRP6, LRP8 (also called apoE receptor 2, APOER2), LRP10, the VLDL receptor (VLDLR), and SORL1 (sortilin related receptor 1; also called sorting protein related receptor containing LDLR class A repeats).

LRP1 is also known as the apoE receptor (APOER), CD91, or α2-macroglobulin receptor (A2MR). This receptor is expressed in numerous tissues and is known to be involved in diverse activities that include lipoprotein transport, modulation of platelet derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFRβ) signaling, regulation of cell-surface protease activity, and the control of cellular entry of bacteria and viruses. Regulation of PDFGRβ activity mediates the protective effects of LRP1 in development of atherosclerosis. LRP1 is synthesized as a 600kDa precursor that is proteolytically processed into a 85kDa transmembrane protein and a 515kDa extracellular protein. The extracellular protein non-covalently associates with the transmembrane protein. LRP1 has been shown to bind more than 40 different ligands that include lipoproteins, extracellular matrix proteins, cytokines and growth factors, protease and protease inhibitor complexes, and viruses. This diverse array of ligands clearly demonstrates that LRP1 is involved in numerous biological and physiological processes.

LRP2 was originally identified as an autoantigen in a rat model of autoimmune kidney disease called Heymann nephritis. LRP2 is expressed in numerous tissues and is found in the apical surfaces of epithelial borders as well as intracellularly in endosomes. In the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidney LRP2 is involved in the reabsorption of numerous molecules. LRP2 binds lipoproteins, hormones, vitamins, vitamin-binding proteins, proteases and, protease inhibitor complexes.

The LRP5 and LRP6 proteins serve as co-receptors in Wnt signaling (see the Signal Transduction by Wnts, TGFs, and BMPs page for more details).

Scavenger Receptors

The founding member of the scavenger receptor family was identified in studies that were attempting to determine the mechanism by which LDL accumulated in macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. Macrophages ingest a variety of negatively charged macromolecules that includes modified LDL such as oxidized LDL (oxLDL). These studies led to the characterization of two types of macrophage scavenger receptors identified as type I and type II.

Subsequent research determined that the scavenger receptor gene family in humans consists of 27 genes. Of these 27 genes 19 encode proteins that have been classified into several subfamilies identified as the class A (SCARA) through class J (SCARJ) receptors, although the class C receptors are only expressed in insects.

After binding ligand the scavenger receptors can either be internalized, similar to the process of internalization of LDL receptors, or they can remain on the cell surface and transfer lipid, or other ligands, into the cell through caveolae or they can mediate adhesion.

Class A Scavenger Receptors

The class A receptors include the SCARA1, SCARA2, SCARA3, SCARA4, and SCARA5 receptors. The SCARA1 protein is encoded by the MSR1 (macrophage scavenger receptor 1) gene. The SCARA2 protein is encoded by the MARCO gene (macrophage receptor with collagenous structure). The SCARA4 protein is encoded by the COLEC12 (collectin subfamily member 12) gene.

The SCARA1 receptor is expressed by macrophages, mast cells, dendritic cells, vascular endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells. SCARA1 has been shown to be a receptor for oxidized LDL (oxLDL) as well as for β-amyloid, apoptotic cells, and bacteria.

Class B Scavenger Receptors

The class B receptors include the SCARB1 (more commonly called SR-B1), SCARB2, and SCARB3 receptors. The SCARB3 protein is encoded by the CD36 gene. The CD36 receptor is also known as fatty acid translocase (FAT; thus often designated CD36/FAT or FAT/CD36) and it is one of the receptors responsible for the cellular uptake of fatty acids as well as for the uptake of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) by macrophages.

The CD36 and SCARB1 genes encode closely related multi-ligand receptors that are most recognized for their roles in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. The role of these receptors in platelet function has recently been the focus of numerous studies. Several of the identified ligands for FAT/CD36 include the gut hormone ghrelin, phosphatidylserine (PS), β-amyloid, serum amyloid A, bacterial lipopeptides, and specific forms of oxidized phospholipids (oxPL) either associated with LDL (referred to as oxLDL) or free that contain an oxidized polyunsaturated fatty acid at the sn-2 position. These latter oxPL are referred to as oxPCCD36 because they are predominantly phosphatidylcholine PL and they bind FAT/CD36.

Class D Scavenger Receptors

Other members of the human scavenger receptor superfamily include the CD68 gene encoded protein (also identified as SCARD1 or SR-D1). Expression of the CD68 gene predominates in immune cells such as monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Like the CD36/FAT receptor, CD68 binds oxLDL.

Class E Scavenger Receptors

The endothelial receptors that bind oxLDL are members of the SR-E family of scavenger receptors. The human SR-E1 (SCARE1) protein is commonly called the LOX-1 receptor (lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1). LOX-1 is also a member of the C-type lectin superfamily of carbohydrate recognition proteins. The receptor is also called the oxidized LDL receptor 1 (OLR1) and as such the LOX-1 protein is encoded by the OLR1 gene. The human SCARE2 protein is encoded by the CLEC7A (C-type lectin domain containing 7A) gene.

Class F Scavenger Receptors

The human SCARF class receptors include the SCARF1 and SCARF2 gene encoded proteins. The SCARF1 protein is also known as SR-F1 or SREC1. The SCARF2 protein is also known as SR-F2 or SREC2.

Class G Scavenger Receptors

The human class G receptor is more commonly called C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 16 (encoded by the CXCL16 gene). CXCL16 is expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells, monocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells and mediates the binding of phosphatidylserine and oxLDL.

Class H Scavenger Receptors

The human SCARH class receptors include SR-H1 and SR-H2, both of which are fasciclin, EGF-like, laminin-type EGF-like and link (FEEL) domain-containing scavenger receptors. The accepted designation for the human SR-H class genes are STAB1 and STAB2 which encode the proteins called stabilin 1 (FEEL-1) and stabilin 2 (FEEL-2), respectively.

Class I Scavenger Receptors

The human class I receptors include two members commonly identified as SCARI1 and SCARI2. The SCARI1 protein is more commonly called CD163 and as such is encoded by the CD163 gene. Expression of CD163 predominates in monocytes and macrophages where it is responsible for hemoglobin recognition and clearance. As a result of this activity the protein is often referred to as the hemoglobin scavenger receptor. The SCARI2 protein is CD163 molecule like 1 which is encoded by the CD163L1 gene.

Class J Scavenger Receptors

The human class J receptor (commonly called SCARJ1) is also referred to as the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products (RAGE). The SCARJ1 protein is encoded by the AGER (advanced glycosylation end-product specific receptor) gene.

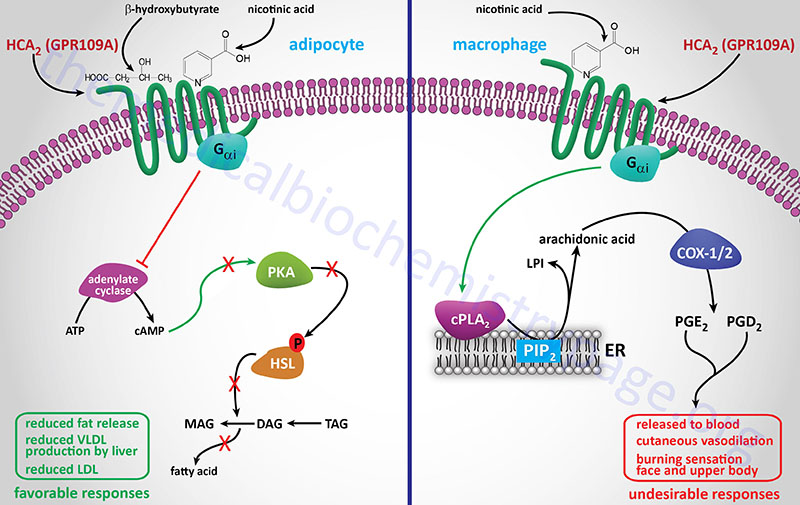

Significance of Macrophage Lipoprotein Receptors