Last Updated: January 2, 2026

Introduction to Hemoglobin and Myoglobin

Myoglobin and hemoglobin are heme containing proteins whose physiological importance is principally related to their ability to bind molecular oxygen. Hemoglobin is a heterotetrameric heme protein of red blood cells where it is responsible for transporting oxygen from the lungs to the tissues. Myoglobin is a monomeric heme protein found mainly in muscle tissue where it serves as an intracellular storage site for oxygen. During periods of oxygen deprivation oxymyoglobin releases its bound oxygen which is then used for metabolic purposes.

Myoglobin

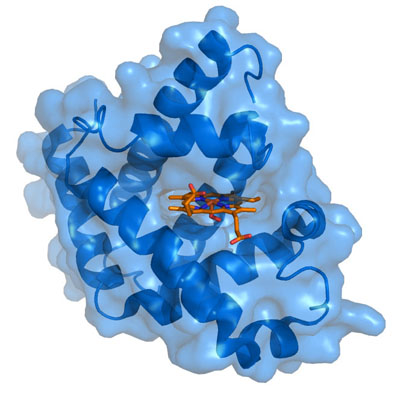

The tertiary structure of myoglobin is that of a typical water soluble globular protein. Its secondary structure is unusual in that it contains a very high proportion (75%) of α-helical secondary structure. A myoglobin polypeptide is comprised of 8 separate right handed α-helices, designated A through H, that are connected by short non helical regions. Amino acid R-groups packed into the interior of the molecule are predominantly hydrophobic in character while those exposed on the surface of the molecule are generally hydrophilic, thus making the molecule relatively water soluble.

Each myoglobin molecule contains one heme prosthetic group inserted into a hydrophobic cleft in the protein. Each heme residue contains one central coordinately bound iron atom that is normally in the Fe2+ (ferrous) oxidation state. The oxygen carried by hemeproteins is bound directly to the ferrous iron atom of the heme prosthetic group. Hydrophobic interactions between the tetrapyrrole ring and hydrophobic amino acid R groups on the interior of the cleft in the protein strongly stabilize the heme protein conjugate. In addition a nitrogen atom from a histidine R group located above the plane of the heme ring is coordinated with the iron atom further stabilizing the interaction between the heme and the protein. In oxymyoglobin the remaining bonding site on the iron atom (the 6th coordinate position) is occupied by the oxygen, whose binding is stabilized by a second histidine residue.

Myoglobin is encoded by the MB gene. The MB gene is located on chromosome 22q12.3 and is composed of 8 exons that generate nine alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode proteins of 154 amino acids (isoform 1) and 99 amino acids (isoform 2). The highest levels of expression of myoglobin are in the heart.

Hemoglobin

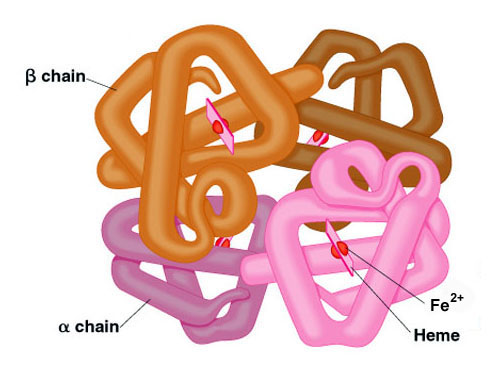

Adult hemoglobin is a [α(2):β(2)] tetrameric hemeprotein found in erythrocytes where it is responsible for binding oxygen in the lung and transporting the bound oxygen throughout the body where it is used in aerobic metabolic pathways.

For a description of the different types of hemoglobin tetramers see the section below on Hemoglobin Genes. Each subunit of a hemoglobin tetramer has a heme prosthetic group identical to that described for myoglobin. The common peptide subunits are designated α, β, γ and δ which are arranged into the most commonly occurring functional hemoglobins.

Although the secondary and tertiary structure of various hemoglobin subunits are similar, reflecting extensive homology in amino acid composition, the variations in amino acid composition that do exist impart marked differences in hemoglobin’s oxygen carrying properties. In addition, the quaternary structure of hemoglobin leads to physiologically important allosteric interactions between the subunits, a property lacking in monomeric myoglobin which is otherwise very similar to the α-subunit of hemoglobin.

Oxygen Binding Characteristics

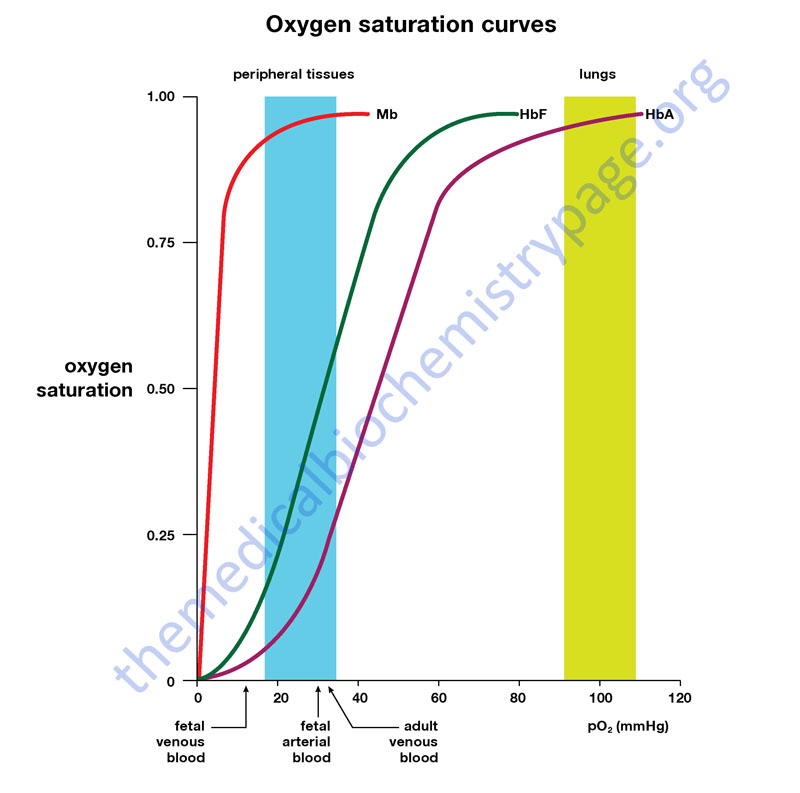

Comparison of the oxygen binding properties of myoglobin and hemoglobin illustrate the allosteric properties of hemoglobin that results from its quaternary structure and differentiate hemoglobin’s oxygen binding properties from that of myoglobin. The curve of oxygen binding to hemoglobin is sigmoidal typical of allosteric proteins in which the substrate, in this case oxygen, is a positive homotropic effector. When oxygen binds to the first subunit of deoxyhemoglobin it increases the affinity of the remaining subunits for oxygen. As additional oxygen is bound to the second and third subunits oxygen binding is further, incrementally, strengthened, so that at the oxygen tension in lung alveoli, hemoglobin is fully saturated with oxygen. As oxyhemoglobin circulates to deoxygenated tissue, oxygen is incrementally unloaded and the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen is reduced. Thus at the lowest oxygen tensions found in very active tissues the binding affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen is very low allowing maximal delivery of oxygen to the tissue. In contrast the oxygen binding curve for myoglobin is hyperbolic in character indicating the absence of allosteric interactions in this process.

The allosteric oxygen binding properties of hemoglobin arise directly from the interaction of oxygen with the iron atom of the heme prosthetic groups and the resultant effects of these interactions on the quaternary structure of the protein. When oxygen binds to an iron atom of deoxyhemoglobin it pulls the iron atom into the plane of the heme. Since the iron is also bound to histidine F8, this residue is also pulled toward the plane of the heme ring. The conformational change at histidine F8 is transmitted throughout the peptide backbone resulting in a significant change in tertiary structure of the entire subunit. Conformational changes at the subunit surface lead to a new set of binding interactions between adjacent subunits. The latter changes include disruption of salt bridges and formation of new hydrogen bonds and new hydrophobic interactions, all of which contribute to the new quaternary structure.

The latter changes in subunit interaction are transmitted, from the surface, to the heme binding pocket of a second deoxy subunit and result in easier access of oxygen to the iron atom of the second heme and thus a greater affinity of the hemoglobin molecule for a second oxygen molecule. The tertiary configuration of low affinity, deoxygenated hemoglobin (Hb) is known as the taut (T) state. Conversely, the quaternary structure of the fully oxygenated high affinity form of hemoglobin (HbO2) is known as the relaxed (R) state.

In the context of the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen there are four primary regulators, each of which has a negative impact. These are CO2, hydrogen ion (H+), chloride ion (Cl–), and 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG, or also just BPG). Some older texts abbreviate 2,3-BPG as 2,3-DPB. Although they can influence O2 binding independent of each other, CO2, H+ and Cl– primarily function as a consequence of each other on the affinity of hemoglobin for O2. We shall consider the transport of O2 from the lungs to the tissues first.

In the high O2 environment (high pO2) of the lungs there is sufficient O2 to overcome the inhibitory nature of the T state. During the O2 binding-induced alteration from the T form to the R form several amino acid side groups on the surface of hemoglobin subunits will dissociate protons as depicted in the equation below. This proton dissociation plays an important role in the expiration of the CO2 that arrives from the tissues (see below). However, because of the high pO2, the pH of the blood in the lungs (≈7.4 – 7.5) is not sufficiently low enough to exert a negative influence on hemoglobin binding O2. When the oxyhemoglobin reaches the tissues the pO2 is sufficiently low, as well as the pH (≈7.2), that the T state is favored and the O2 released.

4 O2 + Hb ↔ nH+ + Hb(O2)4

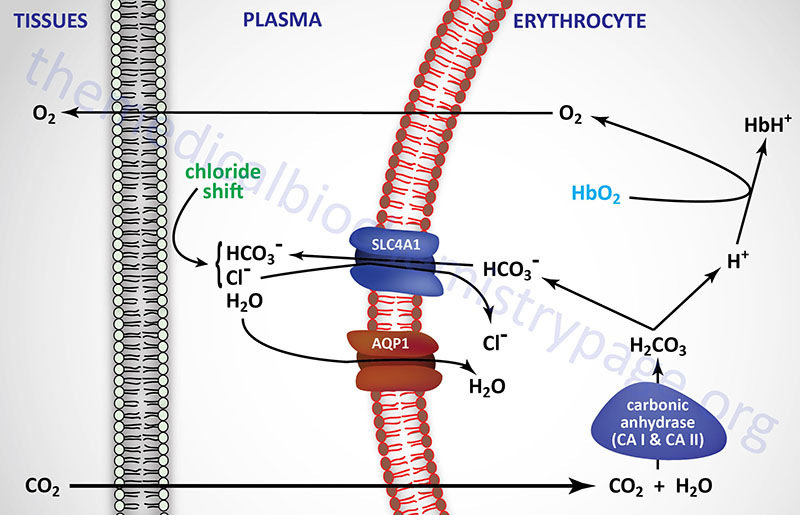

If we now consider what happens in the tissues, it is possible to see how CO2, H+, and Cl– exert their negative effects on hemoglobin binding O2. Metabolizing cells produce CO2 which diffuses into the blood and enters the circulating red blood cells (RBCs). Within RBCs the CO2 is rapidly converted to carbonic acid through the action of carbonic anhydrase as shown in the equation below:

CO2 + H2O ↔ H2CO3 ↔ H+ + HCO3–

The bicarbonate ion produced in this dissociation reaction diffuses out of the RBC and is carried in the blood to the lungs. This effective CO2 transport process is referred to as isohydric transport. Approximately 80% of the CO2 produced in metabolizing cells is transported to the lungs in this way.

The conformation of hemoglobin and its oxygen binding are sensitive to hydrogen ion concentration. These effects of hydrogen ion concentration are responsible for the well known Bohr effect in which increases in hydrogen ion concentration decrease the amount of oxygen bound by hemoglobin at any oxygen concentration (partial pressure). Coupled to the diffusion of bicarbonate out of RBCs in the tissues there must be ion movement into the RBCs to maintain electrical neutrality. This is the role of Cl– and is referred to as the chloride shift. In this way, Cl– plays an important role in bicarbonate production and diffusion and thus also negatively influences O2 binding to hemoglobin.

Carbonic Anhydrases

The carbonic anhydrases (CA) are members of a large family of genes encoding zinc metalloenzymes that possess significant physiological importance. There are five distinct classes of CA found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes identified as α, β, γ, δ, and ε. The α-class of CA are found in mammals. Humans express 15 isoforms of CA with 12 of these isoforms exhibiting functional enzymatic activity. These 12 human catalytic CA isoforms are identified as hCA I–IV, VA, VB, VI, VII, IX, XII, XIII, and XIV. The gene nomenclature for the carbonic anhydrases is CA1-CA4, CA5A, CA5B, CA6, CA7, CA9, CA12, CA13, and CA14). The various CAs differ in catalytic activity, tissue distribution, as well as subcellular localization which includes cytosolic, secreted, membrane-bound, and mitochondrial. The cytoplasmic CA isoforms are CA I, CA II, CA III, CA VII, and CA XIII. The CA II isoform is predominantly expressed in the erythrocyte. The transmembrane CA isoforms are CA IX, CA XII, and CA XIV while the CA isoform that is anchored to the membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linkage is CA IV. The mitochondrial CA isoforms are CA VA and CA VB. The CA VI isoform is a secreted enzyme and is only expressed in salivary glands. Humans express three additional genes designated as carbonic anhydrases due to sequence similarity to functional carbonic anhydrases, however, the encoded proteins do not possess carbonic anhydrase activity. These three genes are designated CA8, CA10, and CA11 and all three are predominantly expressed within the CNS. Although the encoded proteins of these three CA related genes lack CA activity, the importance of the proteins can be demonstrated by the fact that the neurological defect in the lurcher mutant mouse is the result of a loss of CA8 gene expression.

The CAs catalyze the reversible interconversion of CO2 and HCO3– and as such these enzymes are involved in respiration, calcification, acid-base balance, bone resorption, and the formation of aqueous humor, cerebrospinal fluid, saliva, pancreatic exocrine secretions of digestion, and gastric acid. The two CAs expressed in erythrocytes are CA I and CA II, both of which are cytosolic enzymes. The presence of CA in erythrocytes is critical for the transfer of CO2 from the tissues to the lungs. CA I and CA II along with CA VB and CA IX are expressed within the GI tract where they play an important role in overall digestive processes. CA II is found in cerebrospinal fluid and measurement of increases are useful in the diagnosis of various brain diseases. Increased levels of serum CA III are associated with myocardial infarction.

A physiological significance of CAs is related to their role in renal control of acid-base balance and as pharmacologic targets in the control of hypertension, glaucoma, and epilepsy. Several isozymes of carbonic anhydrase are expressed in the human kidney including CA II, CA IV, CA VB, CA XII, CA XIII, and CA XIV. The carbonic anhydrase, CA IX (expression predominately in the gut), is one of only two tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases with CA XII being the other. Expression of CA IX is associated with renal cell carcinomas (RCC) but it is not expressed at all in normal renal tissues which makes it a useful diagnostic marker for this disease.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have a broad spectrum of utility including the treatment of glaucoma, as anti-epileptics, and as diuretics in the treatment of certain forms of hypertension. The CA inhibitors that are diuretics function by inhibiting the CA isoforms present in the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) of the kidney. The major CA expressed in the PCT is CA II. The principal drugs used as diuretics are acetazolamide and methazolamide. The inhibition of CA by these drugs results in bicarbonate retention in the urine, potassium retention in urine and decreased sodium reabsorption. One of the effects of acetazolamide in the kidney is alkalization of the urine. This effect makes acetazolamide useful in the treatment of cystinurias.

CO2 Transport

A small percentage of CO2 is transported in the blood as a dissolved gas. In the tissues, the H+ dissociated from carbonic acid is buffered by hemoglobin which exerts a negative influence on O2 binding forcing release to the tissues. As indicated above, within the lungs the high pO2 allows for effective O2 binding by hemoglobin leading to the T to R state transition and the release of protons. The protons combine with the bicarbonate that arrived from the tissues forming carbonic acid which then enters the RBCs. Through a reversal of the carbonic anhydrase reaction, CO2 and H2O are produced. The CO2 diffuses out of the blood, into the lung alveoli and is released on expiration.

In addition to isohydric transport, as much as 15% of CO2 is transported to the lungs bound to N-terminal amino groups of the T form of hemoglobin. This reaction, depicted below, forms what is called carbamino-hemoglobin. As indicated this reaction also produces H+, thereby lowering the pH in tissues where the CO2 concentration is high. The formation of H+ leads to release of the bound O2 to the surrounding tissues. Within the lungs, the high O2 content results in O2 binding to hemoglobin with the concomitant release of H+. The released protons then promote the dissociation of the carbamino to form CO2 which is then released with expiration.

CO2 + Hb-NH2 ↔ H+ + Hb-NH-COO–

Methemoglobin

Oxidation of the ferrous (Fe2+) iron to the ferric (Fe3+) oxidation state renders a globin monomer incapable of normal oxygen binding. When one or more of the heme iron molecules exists in the ferric state the hemoglobin is termed methemoglobin. Formation of the reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide anion, can occur in erythrocytes (red blood cell, RBC) as a result of O2 oxidation of ferrous iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+) in hemoglobin. The consequence of the latter reaction is the generation of methemoglobin. Since hemoglobin is a heterotetramer, and each subunit contains Fe2+ iron in its heme there is the potential for multiple Fe3+ irons to be present in methemoglobin. The Fe3+ form of iron does not bind O2, however, the presence of at least one Fe3+ in the hemoglobin tetramer results in enhanced binding of the O2 to the remaining Fe2+ irons causing reduced delivery of the O2 to the tissues with potential for cyanosis. Normal daily levels of methemoglobin range from 0.5%–3%.

The ferric iron in methemoglobin is reduced to ferrous iron via the action of the NADH-requiring enzyme, methemoglobin reductase (cytochrome b5 reductase 3: CYB5R3). The CYB5R3 encoded protein is soluble in erythrocytes but is membrane bound in other cells types. The membrane-bound form is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes where it participates in the elongation and desaturation of fatty acids, in the synthesis of cholesterol, and in xenobiotic metabolism. Humans express four cytochrome b5 reductase genes, CYB5R1, CYB5R2, CYB5R3, and CYB5R4.

The NADPH produced in the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the antioxidant glutathione (GSH), are both necessary for the continual removal of ROS from within the erythrocyte.

Carbon Monoxide, CO

Carbon monoxide (CO) also binds coordinately to heme iron atoms in the ferrous state (Fe2+) in hemoglobin in a manner similar to that of oxygen. However, the binding of CO to heme iron is much stronger (>200 fold) than that of O2. When CO is bound to hemoglobin the resulting protein is referred to as carboxyhemoglobin (HbCO). In addition to a higher affinity of CO over that of O2 for ferrous iron in hemoglobin, the result of CO binding to at least one globin monomer is that any O2 bound to other heme moieties will not release in the tissues under the conditions that would normally promote O2 dissociation. This is sometimes expressed as a higher affinity for O2 in carboxhemoglobin but this is mechanistically incorrect. This effect contributes to reduced O2 release in the tissues. Hemoglobin monomers in carboxyhemoglobin that do not have O2 bound will have a very low affinity to bind O2. These combined effects of the preferential binding of CO to heme iron, poor dissociation of any bound O2, and reduced affinity for O2 binding is largely responsible for the hypoxia that results from carbon monoxide poisoning.

Role of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG)

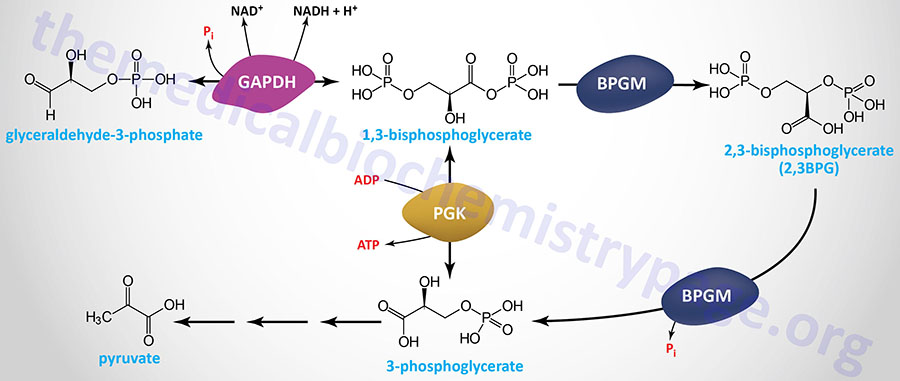

The compound 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), derived from the glycolytic intermediate 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, is a potent allosteric effector on the oxygen binding properties of hemoglobin. The pathway of red blood cell 2,3BPG synthesis is referred to as the Rapoport–Luebering shunt and is diagrammed in the Figure below.

The bifunctional enzyme, bisphosphoglycerate mutase (encoded by the BPGM gene) diverts some of the 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate from the glycolytic pathway into 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate through the action of the synthase function of the enzyme. The conversion of 2,3-BPG to 3-phosphoglycerate is catalyzed by the phosphatase function of BPGM.

In the deoxygenated T conformation, a cavity capable of binding 2,3-BPG forms in the center of the hemoglobin tetramer. A single molecule of 2,3-BPG can occupy this cavity which thereby, stabilizes the T state. The interaction of 2,3-BPG with deoxyhemoglobin occurs via salt bridges with Lys and His residues in the β-globin subunits of the hemoglobin tetramer. Conversely, when 2,3-BPG is not available, or not bound in the central cavity, Hb can bind oxygen (forming HbO2) more readily. Thus, like increased hydrogen ion (H+) concentration, increased 2,3-BPG concentration favors conversion of R form Hb to T form Hb and decreases the amount of oxygen bound by Hb at any oxygen concentration. When the oxygen pressure is high enough, such as in the alveoli of the lungs, the binding of a mole of O2 induces the T-to-R transition which causes the 2,3-BPG binding pocket to collapse and the 2,3-BPG is expelled allowing for the rest of the monomers of globin protein to bind O2.

Hemoglobin molecules differing in subunit composition are known to have different 2,3-BPG binding properties with correspondingly different allosteric responses to 2,3-BPG. For example, HbF (the fetal form of hemoglobin) is composed of two α-proteins and two γ-proteins. Although the γ-globin and β-globin proteins are 72% identical at the amino acid level one significant amino acid difference exists in the 2,3-BPG binding pocket. In the γ-globin protein, His 143 is replaced by a Ser in the 2,3-BPG-binding site. The effect of this amino acid substitution is the loss of two positive charges (one from each γ-subunit relative to the β-subunits). The result is that 2,3-BPG is bound much less avidly to HbF than to HbA (the adult form of hemoglobin). The consequences are that HbF in the fetus binds oxygen with greater affinity than the mother’s HbA, thus giving the fetus preferential access to oxygen carried by the mothers circulatory system.

Regulation of 2,3BPG Synthesis and High Altitude Acclimation

It has been known for more than 50 years that 2,3-BPG levels increase in the erythrocytes of normal individuals who have acclimated to life at high altitudes (hypoxic conditions). The precise molecular basis for this phenomenon has only recently been fully appreciated.

Contributing to erythrocyte metabolic reprogramming at high altitude, as well as under other hypoxic conditions, is an increase in plasma levels of adenosine. Associated with increasing adenosine concentration is increased erythrocyte synthesis of the potent bioactive lipid, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). Both of these processes function in concert to reprogram metabolism in erythrocytes resulting in increased 2,3BPG synthesis.

At high altitude, as well as under other hypoxic conditions, increased levels of soluble 5′-nucleotidase, ecto (encoded by the NT5E gene), a normally membrane-associated enzyme, result in increased conversion of extracellular AMP to adenosine. Adenosine exerts effects, such as in neurotransmission, by binding to specific receptors. The adenosine receptor on erythrocytes, A2B, is encoded by the ADORA2B gene. One of the responses to activation of A2B is increased PKA activity. One of the substrates of PKA is sphingosine kinase 1 (encoded by the SPHK1 gene ) which leads to its activation and a resulting increase in S1P production. Combined with the actions of S1P and the activation of the A2B receptor is increased 2,3BPG synthesis.

The most abundant membrane protein in erythrocytes was originally identified as band 3, now known as anion exchanger 1 (AE1) which is encoded by the SLC4A1 gene. The intracellular N-terminal domain of AE1 binds to several glycolytic enzymes including PFK-1, aldolase A, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. One of the consequences of increased erythrocyte S1P is the release of these glycolytic enzymes from AE1 resulting in an increase in glycolysis and subsequently, increased 2,3BPG synthesis. In addition to activation of PKA, A2B activates AMPK which directly phosphorylates BPGM further enhancing synthesis of 2,3BPG.

The Hemoglobin Genes

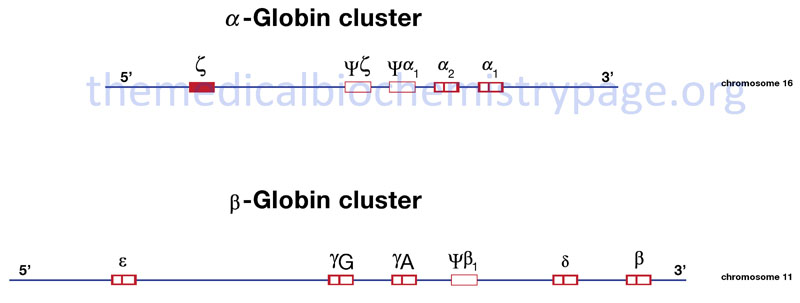

The α- and β-globin proteins contained in functional hemoglobin tetramers are derived from gene clusters. The α-globin genes are on chromosome 16 and the β-globin genes are on chromosome 11. Both gene clusters contain not only the major adult α and β protein encoding genes, but other expressed genes that are utilized at different stages of development. The orientation of the genes in both clusters is in the same 5′ to 3′ direction with the earliest expressed genes at the 5′ end of both clusters. In addition to functional genes, both clusters contain non-functional pseudogenes.

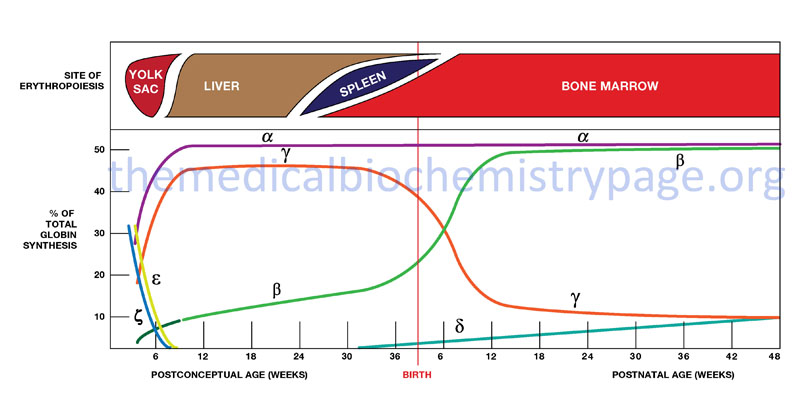

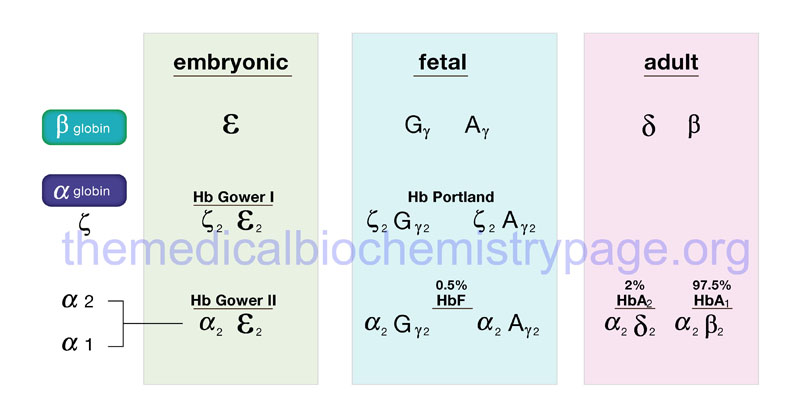

Hemoglobin synthesis begins in the first few weeks of embryonic development within the yolk sac. The major hemoglobin at this stage of development is a tetramer composed of two zeta (ζ) chains encoded by the HBZ gene within the α cluster and two epsilon (ε) chains encoded by the HBE1 gene within the β cluster. By 6–8 weeks of gestation the expression of this version of hemoglobin declines dramatically coinciding with the change in hemoglobin synthesis from the yolk sac to the liver. Expression from the α cluster consists of identical proteins, α1 and α2, encoded by the HBA1 and HBA2 genes. Expression from these genes in the α cluster remains on throughout life.

Within the β-globin cluster there is an additional set of genes, the fetal β-globin genes identified as the gamma (γ) genes. The two fetal genes, HBG1 and HBG2, encode proteins identified as Aγ and Gγ, respectively. The derivation of the “A” and “G” designations stems from the single amino acid difference between the two fetal genes: glycine in Gγ and alanine in Aγ at position 136. These fetal γ genes are expressed as the embryonic genes are turned off.

Shortly before birth there is a smooth switch from fetal γ-globin gene expression to adult β-globin gene (HBB) expression. The switch from fetal γ- to adult β-globin does not directly coincide with the switch from hepatic synthesis to bone marrow synthesis since at birth it can be shown that both γ and β synthesis is occurring in the bone marrow.

Given the pattern of globin gene activity throughout fetal development and in the adult the composition of the hemoglobin tetramers is of course distinct. Fetal hemoglobin is identified as HbF and includes both α2Gγ2 and α2Aγ2. Fetal hemoglobin has a higher affinity for oxygen than does adult hemoglobin (HbA1 and HbA2) as a result of HbF having reduced binding capacity for 2,3-BPG. This allows the fetus to extract oxygen more efficiently from the maternal circulation.

In adults the major hemoglobin is identified as HbA (more commonly HbA1) and is a tetramer of two α and two β chains as indicated earlier. A minor adult hemoglobin, identified as HbA2, is a tetramer of two α chains and two δ chains. The δ gene (HBD) is expressed with a timing similar to the β gene (HBB) but because the promoter has acquired a number of mutations its’ efficiency of transcription is reduced. The overall hemoglobin composition in a normal adult is approximately 97.5% HbA1, 2% HbA2 and 0.5% HbF.

Hemoglobinopathies

A large number of mutations have been described in the globin genes including both the α-globin cluster and the β-globin cluster. These mutations can be divided into two distinct types: those that cause qualitative abnormalities (e.g. sickle cell anemia) and those that cause quantitative abnormalities (the thalassemias). Taken together these disorders are referred to as the hemoglobinopathies. A third group of hemoglobin disorders include those diseases in which there is a persistence of fetal hemoglobin expression. These latter diseases are known collectively as hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH).

Hemoglobin S

Of the mutations leading to qualitative alterations in hemoglobin, the missense mutation in the β-globin gene that causes sickle cell anemia is the most common. The mutation causing sickle cell anemia is a single nucleotide substitution (A to T) in the codon for amino acid 6. The change converts a Glu codon (GAG) to a Val codon (GTG). The form of hemoglobin in persons with sickle cell anemia is referred to as HbS. Inheritance of sickle cell anemia is autosomal recessive, however, in some individuals under certain conditions (e.g. infections and drug therapies) pathology can be observed in the heterozygous state (i.e. HbA/HbS).

The underlying problem in sickle cell anemia is that the Val for Glu substitution results in hemoglobin tetramers that aggregate into arrays upon deoxygenation in the tissues. This aggregation leads to deformation of the red blood cell making it relatively inflexible and unable to traverse the capillary beds. Repeated cycles of oxygenation and deoxygenation lead to irreversible sickling. The end result is clogging of the fine capillaries. Because bones are particularly affected by the reduced blood flow, frequent and severe bone pain results. This is the typical symptom during a sickle cell “crisis”. Long term the recurrent clogging of the capillary beds leads to damage to the internal organs, in particular the kidneys, heart and lungs. The continual destruction of the sickled red blood cells leads to chronic anemia and episodes of hyperbilirubinemia.

Hemoglobin C

An additional relatively common mutation at codon 6 is the conversion to a Lys codon (AAG) which results in the generation of HbC. Like sickle cell anemia, HbC disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive condition. Homozygous HbC/HbC individuals manifest a relatively benign disease consisting of mild hemolytic anemia, mild splenomegaly, and blood smears that show the presence of codocytes (target cells). Hemoglobin C proteins precipitate forming dense rectangular structures seen in blood smears and referred to as HbC crystals. HbC homozygous individuals may appear to have a very mild form of sickle cell anemia.

In compound heterozygotes expressing an HbS and an HbC allele (SC disease, or HbSC disease) there is a much more significant pathology that is severe. The clinical spectrum observed in HbSC individuals is somewhat of a paradox given that neither the heterozygous HbS/A and the HbC/A genotypes manifest with significant pathology. HbSC disease is clinically characterized as a form of sickle cell disease with symptoms that include episodes of hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusive crises, and splenomegaly.

Hemoglobin E

Hemoglobin E is a form of hemoglobin resulting from mutation at amino acid 26 in the β-globin gene. This mutation changes the normal Glu (GAG) residue to a Lys (AAG). In addition to the change in amino acid sequence resulting in a qualitative hemoglobinopathy, the HbE mutation results in the generation of a cryptic splice site at codons 25–27 that results in 40% of β-globin mRNA being shorter than normal by 16 nucleotides. This shortened β-globin mRNA does not give rise to detectable β-globin protein, typical of quantitative β-thalassemias.

The HbE form of hemoglobin is quite common in individuals of Southeast Asian descent. Hemoglobin E disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive disease where homozygous individuals (HbE/HbE) experience a mild form of β-thalassemia in the post-natal period. Heterozygotes (HbA/HbE) do not show any symptoms. Homozygotes for the HbE allele do not exhibit symptoms at birth because of the presence of normal fetal hemoglobin (HbF).

Symptoms will begin to appear after the expression of the γ-globin gene ceases and the adult β-globin gene is activated. The typical symptoms are mild hemolytic anemia and mild splenomegaly. Serious pathology is present in individuals who are compound heterozygotes harboring one HbE allele and one β-thalassemia allele (HbE/β-thal). These individuals experience growth impairment, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperbilirubinemia (presenting as jaundice), bone abnormalities, and cardiovascular issues.

Hemoglobin M

Hemoglobin M (HbM) refers to group of autosomal dominant methemoglobinemias that are caused by heterozygous mutations in either the α- or β-globin genes. These mutations result in the production of what is referred to as M hemoglobin (HbM) which is a form of hemoglobin that stabilizes the heme iron in the ferric (Fe3+) state and which is not amenable to reduction. The designation HbM also can refer to a form of hemoglobin that exhibits an unusual susceptibility to oxidizing agents.

At least thirteen different forms of hemoglobin M have been characterized. Several of these, including the HbM (Boston), HbM (Hyde Park), HbM (Iwate), and HbM (Saskatoon), are due to mutations that alter the critical His residues to Tyr in the heme binding pocket of either α-globin or β-globin proteins. These positions are defined as either the proximal (F8) or the distal (E7) His residues. The proximal F8 His position is amino acid 87 in the α-globin proteins and is amino acid 92 in the βb-globin proteins. The distal E7 His position is amino acid 58 in the α-globin proteins and is amino acid 63 in the β-globin proteins.

The HbM (Milwaukee-1) form results from a Glu for Val substitution at a position four amino acid residues from the distal His of the heme binding pocket. These mutations all stabilize the heme iron in the ferric (oxidized) state.

The primary pathology in patients harboring HbM mutations is cyanosis but otherwise they are asymptomatic. If the HbM mutation is in the α-globin gene the cyanosis is apparent at birth. If the HbM mutation is in the β-globin gene then cyanosis appears later or intensifies when β-subunit production increases. Neonates that harbor mutations in the γ-globin gene will exhibit cyanosis at birth but it will disappear when the complete γ-globin to β-globin gene expression switch occurs.

Hemoglobin Electrophoresis

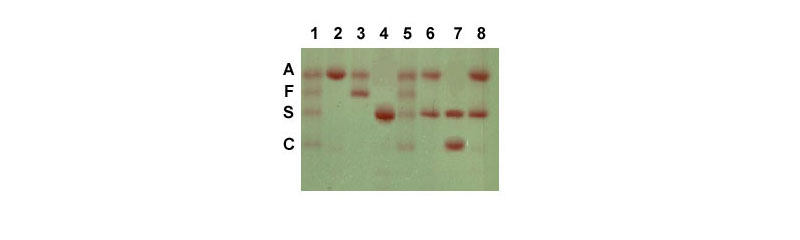

Electrophoresis of hemoglobin proteins from individuals suspected of having sickle cell anemia (or several other types of hemoglobin disorders) is an effective diagnostic tool because the variant hemoglobins have different charges and thus, migrate differently in gel electrophoresis. An example of this technique is shown in the Figure below.

Another effective tool to identify the genotype of individuals suspected of having sickle cell disease as well as for prenatal diagnosis is to either carry out RFLP mapping or to use PCR. An example of the use of these tools can be seen in the Molecular Tools of Medicine page.

In addition to the missense mutations that lead to HbS, HbC, HbE, and HbM, a number of frameshift mutations leading to qualitative abnormalities in hemoglobin have been identified. A 2-nucleotide insertion between codons 144 and 145 in the β-globin gene results in the generation of hemoglobin Cranston. The insertion, which is near the C-terminus of the β-globin protein, results in the normal stop codon being out of frame and synthesis proceeding into the 3′-untranslated region to a fortuitous stop codon. The result is a β-globin protein of 157 amino acids.

In the hemoglobin Constant Spring variant, a mutation in the α-globin gene converts the stop codon (UAA) to a glutamine (Gln) codon (CAA) so that the protein ends up being 31 amino acids longer than normal. The resultant α-globin protein in hemoglobin Constant Spring is not only qualitatively altered but because it is unstable it is a quantitative abnormality as well.

Because the globin gene locus contains clusters of similar genes there is the potential for unequal cross over between the sister chromatids during prophase of meiosis I. The generation of the hemoglobin Gun Hill and Lepore hemoglobins are both the result of unequal cross over events. Hemoglobin Gun Hill is the result of a deletion of 15 nucleotides caused by unequal cross over between codons 91–94 of one β-globin gene and codons 96–98 of the other. Generation of Lepore hemoglobins results from unequal cross over between the δ-globin and β-globin genes. The resultant hybrid δβ gene is called Lepore and the βδ hybrid gene is called anti-Lepore. As indicated earlier, the promoter of the δ-globin gene is inefficient so the consequences of this unequal cross over event are both qualitative and quantitative.

Thalassemias

The thalassemias are quantitative hemoglobinopathies that result from abnormalities in hemoglobin synthesis and affect both α-globin and β-globin gene clusters. Deficiencies in β-globin synthesis result in the β-thalassemias and deficiencies in α-globin synthesis result in the α-thalassemias. The term thalassemia is derived from the Greek word thalassa meaning “sea” and was applied to these disorders because of the high frequency of their occurrence in individuals living around the Mediterranean Sea.

In normal individuals an equal amount of both α- and β-globin proteins are made allowing them to combine stoichiometrically to form the correct hemoglobin tetramers. In the α-thalassemias normal amounts of β-globin are made but not the α-globin proteins. The β-globin proteins are capable of forming homotetramers (β4) and these tetramers are called hemoglobin H, (HbH). An excess of HbH in red blood cells leads to the formation of inclusion bodies commonly seen in patients with α-thalassemia. In addition, the HbH tetramers have a markedly reduced oxygen carrying capacity. In β-thalassemia, where the β-globins are deficient, the α-globins are in excess and will form α-globin homotetramers. The α-globin homotetramers are extremely insoluble which leads to premature red cell destruction in the bone marrow and spleen.

With the α-thalassemias the level of α-globin production can range from none to very nearly normal levels. This is due in part to the fact that there are two identical α-globin genes on chromosome 16. Thus, the α-thalassemias involve inactivation of one to all four α-globin genes. If three of the four α-globin genes are functional, individuals are completely asymptomatic. This situation is identified as the “silent carrier” state or sometimes as α-thalassemia 2. Genotypically this situation is designated αα/α– (where the dash indicates a non-functional gene) or α–/αα. If two of the four genes are inactivated, individuals are designated as α-thalassemia trait or as α-thalassemia 1. Genotypically this situation is designated αα/– –. In individuals of African descent with α-thalassemia 1, the disorder usually results from the inactivation of one α-globin gene on each chromosome and is designated α–/α–. This means that these individuals are homozygous for the α-thalassemia 2 chromosome. The phenotype of α-thalassemia 1 is relatively benign. The mean red cell volume (designated MCV in clinical tests) is reduced in α-thalassemia 1 but individuals are generally asymptomatic.

The clinical situation becomes more severe if only one of the four α-globin genes is functional. Because of the dramatic reduction in α-globin chain production in this latter situation, a high level of β4 tetramer is present. Clinically this is referred to as hemoglobin H (HbH) disease. Afflicted individuals have moderate to marked anemia and their MCV is quite low, but the disease is not fatal.

The most severe situation results when no α-globin chains are made (genotypically designated – –/– –). This leads to prenatal lethality or early neonatal death. The predominant fetal hemoglobin in afflicted individuals is a tetramer of γ-chains and is referred to as hemoglobin Barts. This hemoglobin has very high affinity for oxygen resulting in poor oxygen release and thus, oxygen starvation in the fetal tissues. Heart failure results as the heart tries to pump more oxygenated blood to oxygen starved tissues leading to marked edema. This latter situation is called hydrops fetalis.

A large number of mutations have been identified leading to decreased or absent production of β-globin chains resulting in the β-thalassemias. In the most severe situation mutations in both the maternal and paternal β-globin genes leads to loss of normal amounts of β-globin protein. A complete lack of HbA is denoted as β0-thalassemia. If one or the other mutations allows production of a small amount of functional β-globin then the disorder is denoted as β+-thalassemia.

Both β0 and β+ thalassemias are referred to as thalassemia major, also called Cooley’s anemia after Dr. Thomas Cooley who first described the disorder. Afflicted individuals suffer from severe anemia beginning in the first year of life leading to the need for blood transfusions. As a consequence of the anemia the bone marrow dramatically increases its’ effort at blood production. The cortex of the bone becomes thinned leading to pathologic fracturing and distortion of the bones in the face and skull. In addition, there is marked hepatosplenomegaly as the liver and spleen act as additional sites of blood production. Without intervention these individuals will die within the decade of life. As indicated, β-thalassemia major patient require blood transfusions, however, in the long term these transfusions lead to the accumulation of iron in the organs, particularly the heart, liver and pancreas. Organ failure ensues with death in the teens to early twenties. Iron chelation therapies appear to improve the outlook for β-thalassemia major patients but this requires continuous infusion of the chelating agent.

Individuals heterozygous for β-thalassemia have what is termed thalassemia minor. Afflicted individuals harbor one normal β-globin gene and one that harbors a mutation leading to production of reduced or no β-globin. Individuals that do not make any functional β-globin protein from one gene are termed β0 heterozygotes. If β-globin production is reduced at one locus the individuals are termed β+ heterozygotes. Thalassemia minor individuals are generally asymptomatic.

The term thalassemia intermedia is used to designate individuals with significant anemia and who are symptomatic but unlike thalassemia major do not require transfusions. This syndrome results in individuals where both β-globin genes express reduced amounts of protein or where one gene makes none and the other makes a mildly reduced amount. A person who is a compound heterozygote with α-thalassemia and β+-thalassemia will also manifest as thalassemia intermedia.

The primary cause of α-thalassemias is deletion, whereas for β-thalassemias the mutations are more subtle. In β-thalassemias, point mutations in the promoter, mutations in the translational initiation codon, a point mutation in the polyadenylation signal, and an array of mutations leading to splicing abnormalities have been characterized.

Hereditary Persistence of Fetal Hemoglobin: HPFH

There are some individuals in whom the developmental timing of globin production is altered as a consequence of mutation. Persons with hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH) continue to make fetal hemoglobin (HbF) as adults. Whereas individuals with γβ thalassemia have modestly elevated levels of HbF and a mild but definite thalassemia phenotype of hypochromia and microcytosis, HPFH is usually not associated with hypochromia and microcytosis in heterozygotes. Because the HPFH syndrome is benign most individuals do not even know they carry a hemoglobin abnormality. Many HPFH individuals harbor deletions in the δ-globin and/or β-globin gene coding regions of within the β-globin gene cluster. In addition some HPFH individuals harbor mutations in the promoter region of the fetal γ-globin genes. Individuals who are homozygous for HPFH mutations lack all HbA1 and HbA2 forms of adult hemoglobin.

Six different deletions have been identified in the β-globin gene cluster that are associated with a phenotype of HPFH. The HPFH-1 and HPFH-2 deletions represent large deletions across the δ- and β-globin genes. The HPFH-1 and HPFH-2 deletions are of nearly identical size and span approximately 105 kb of DNA. The HPFH-3 and HPFH-4 deletions are less extensive. These two deletions encompass approximately 50 kb and 40 kb, separated by approximately 2 kb, and they are located approximately 30 kb downstream from the position of the β-globin gene. The HPFH-5 deletion is a relatively short deletion that extends from a point approximately 3 kb 5′ of the δ-globin gene to a point 700 bp 3′ of the β-globin gene. The HPFH-5 deletion is proximal (3′) to the position of the 3′ enhancer of the β-globin gene. The HPFH-6 deletion is approximately 101 kb but is more in the 5′ direction and is associated with deletion of the fetal Aγ-globin gene.

A number of different point mutations in the promoter regions of the fetal γ-globin genes have been identified in HPFH individuals. The majority of these promoter mutations affect the Aγ-globin gene. In either situation the result is overexpression of the fetal γ-globin genes. These point mutations have been found to be clustered in three distinct regions of the 5′-flanking DNA of the affected γ-globin genes. In one of these regions five different mutations have been characterized, all in the an area 200 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site of the γ-globin genes. Four of these mutations are in the promoter region of the Aγ-globin gene and one in the promoter region of the Gγ-globin gene. These mutations all reside in GC-rich regions of these two genes which is a region known to bind the transcription factor, Sp1.

In addition to Sp1 binding, this region of the γ-globin genes also binds another transcriptional regulatory complex that is erythroid cell specific. The second promoter region mutation region is located at position -175. A point mutation, changing a T to a C is found at this location in either of the γ-globin genes. This region of both genes contains binding sites for the transcription factors OCT-1 and GATA-1. The point mutation at position -175 affects the one nucleotide that is present in the partially overlapping binding sites for both of these transcription factors. The third region affected by a point mutation is in the region of the CCAAT box of the Aγ-globin gene. Another mutation in the Aγ-globin gene resulting in a similar phenotype involves the deletion of 13 base pairs of DNA from position -102 to -114 that encompasses the CCAAT box element. A third mutation has also been identified that involves the CCAAT box of the Gγ-globin gene.