Last Updated: December 24, 2025

Introduction to Glycogen Metabolism

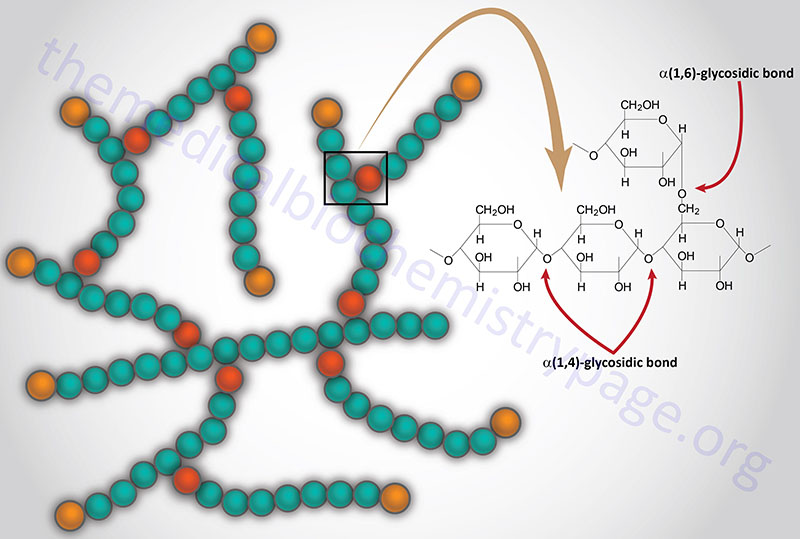

Glycogen is a polymer of glucose residues linked by α-(1,4)- and α-(1,6)-glycosidic bonds. Stores of readily available glucose, to supply the tissues of the body with an oxidizable energy source, are found as glycogen, solely in the liver. Although the liver is the only tissue that can release glucose from glycogen to the blood, other tissues such as skeletal muscle, brain, kidney, heart, and adipose tissue are all capable of glycogen synthesis and breakdown.

The glucose in muscle and brain glycogen, and other non-hepatic tissues, is not available to other tissues, because of the presence of hexokinase which has a very high affinity for glucose, thereby rapidly phosphorylating any glucose which traps it inside the cell. In addition, these non-hepatic tissues lack expression of the enzyme, glucose-6-phosphatase, which is required for the removal of phosphate from glucose.

The major site of daily glucose consumption (75%) is the brain via aerobic pathways. Most of the remainder of the glucose is utilized by erythrocytes, skeletal muscle, and heart muscle. The body obtains glucose either directly from the diet or from amino acids and lactate, and to a lesser extent from glycerol, via gluconeogenesis. Glucose obtained from these two primary sources either remains soluble in the body fluids or is stored in a polymeric form as glycogen.

With up to 10% of its weight as glycogen, the liver has the highest specific content of any body tissue. Muscle has a much lower amount of glycogen per unit mass of tissue (1%–2%), but since the total mass of muscle is so much greater than that of liver, total glycogen stored in muscle is about twice that of liver. The amount of glycogen in the brain is on the order of 0.1% of total tissue weight. Stores of glycogen in the liver are considered the main buffer of blood glucose levels.

Glycogen homeostasis involves the concerted regulation of the rate of glycogen synthesis (glycogenesis) and the rate of glycogen breakdown (glycogenolysis). These two processes are reciprocally regulated such that hormones that stimulate glycogenolysis (e.g. glucagon, cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine) simultaneously inhibit glycogenesis. Conversely, insulin, which directs the body to store excess carbon for future use, stimulates glycogenesis while simultaneously inhibiting glycogenolysis.

Glycogenolysis

Cytosolic Glycogen Catabolism

Degradation of stored glycogen, termed glycogenolysis, occurs through one of two pathways, cytosolic and lysosomal. The cytosolic pathway involves the actions of glycogen phosphorylase (GP; often referred to simply as phosphorylase) and the glycogen debranching enzyme (GDE). Within the cytosolic compartment, in particular in skeletal muscle, approximately 40% of glycogen phosphorylase is associated with membranes of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR: muscle cell endoplasmic reticulum, ER).

As discussed below glycogen phosphorylase activity is regulated by its state of phosphorylation, a reaction catalyzed by phosphorylase kinase (PHK: also called glycogen synthase glycogen phosphorylase kinase). In skeletal muscle cells approximately 55% of PHK activity is associated with the SR. The association of glycogen phosphorylase and PHK on SR membranes allows for rapid glycogenolysis in response to muscle cell activation and release of SR stored Ca2+.

The activity of PHK is itself regulated by phosphorylation and by its Ca2+-binding subunit, calmodulin. PHK belongs to the family of Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent kinases (CaMK) that have restricted substrate specificity.

Humans express three genes encoding proteins with glycogen phosphorylase activity. One gene (PYGL) expresses the hepatic form of the enzyme, a second (PYGM) expresses the muscle form (referred to as myophosphorylase), and the third (PYGB) expresses the brain form. The liver form of phosphorylase is often designated GP-LL, the muscle form as GP-MM, and the brain as GP-BB. Due to different levels of expression and forms of phosphorylase the brain contains three isoforms: GP-BB (~65%), GP-BB+MM (~30%), and GP-MM (~5%). The heart also contains multiple isoforms: GP-BB (~60%), GP-BB+MM (~30%), and GP-MM (~10%. However, the liver exclusively contains the GP-LL isoform and skeletal muscle contains exclusively the GP-MM isoform.

The PYGM gene is located on chromosome 11q13.1 and is composed of 20 exons that generate two splice variant mRNAs. The two different PYGM proteins that result are referred to as isoform 1 (842 amino acids) and isoform 2 (754 amino acids).

The PYGL gene is located on chromosome 14q22.1 and, like the PYGM gene, is composed of 20 exons that generate two splice variant mRNAs. The two different PYGL proteins that result are referred to as isoform 1 (872 amino acids) and isoform 2 (813 amino acids).

The PYGB gene is located on chromosome 20p11.21 and is also composed of 20 exons that encode a protein of 843 amino acids. Although preferentially expressed in the brain, expression of the PYGB gene occurs in adult liver and skeletal muscle, as well as several other tissues.

The enzymatic functions of the different glycogen phosphorylase gene encoded enzymes are identical but their mechanisms of regulation have tissue specific characteristics in addition to some similarities. In addition, mutations in specific glycogen phosphorylase genes explain the tissue-specific nature of several of the glycogen storage diseases.

Biologically active glycogen phosphorylase exists as a homodimer. Each subunit binds the vitamin B6-derived cofactor, pyridoxal phosphate, PLP. In addition to the PLP-binding sites and the catalytic sites of homodimeric glycogen phosphorylase, the enzyme contains allosteric regulatory sites and phosphorylation sites as detailed in the section below covering Regulation of Glycogen Catabolism.

The majority of glycogen phosphorylase is bound to glycogen granules through a domain referred to as the glycogen storage site. The binding to glycogen allows glycogen phosphorylase to rapidly release stored glucose in response to physiological demands.

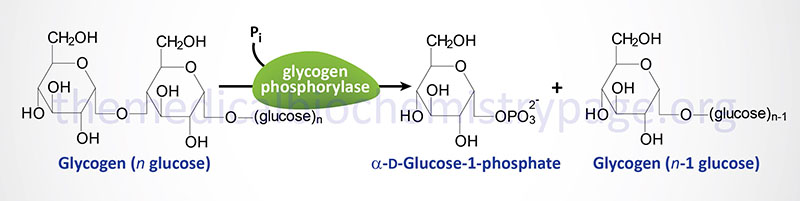

The catalytic action of glycogen phosphorylase is to phosphorolytically remove single glucose residues from α-(1,4)-linkages within the glycogen molecules. The product of this reaction is glucose-1-phosphate and a glycogen molecule with one less glucose residue. The advantage of the reaction proceeding through a phosphorolytic step is that:

1. The glucose is removed from glycogen is an activated state, i.e. phosphorylated and this occurs without ATP hydrolysis.

2. The concentration of Pi in the cell is high enough to drive the equilibrium of the reaction in the favorable direction since the free energy change of the standard state reaction is positive.

The glucose-1-phosphate produced by the action of glycogen phosphorylase is converted to glucose-6-phosphate by phosphoglucomutase (phosphohexose mutase). This enzyme, like phosphoglycerate mutase of glycolysis, contains a phosphorylated amino acid in the active site (in the case of phosphoglucomutase it is a Ser residue). The enzyme phosphate is transferred to C-6 of glucose-1-phosphate generating glucose-1,6-bisphosphate as an intermediate. The phosphate on C-1 is then transferred to the enzyme regenerating active enzyme and glucose-6-phosphate is the released product.

There are four different phosphoglucomutase genes in humans identified as PGM1, PGM2, PGM3, and PGM5. The protein encoded by the PGM5 gene is called phosphoglucomutase-like protein 5. The PGM1 gene is expressed in most tissues, whereas PGM2 expression predominates in red blood cells.

The PGM1 gene is located on chromosome 1p31.3 and is composed of 13 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs and three isoforms of this enzyme. Mutations in the PGM1 gene are associated with the congenital disorder of glycosylation, CDG1T (once referred to as glycogen storage disease type 14, GSD14).

The PGM2 gene is located on chromosome 4p14 and is composed of 15 exons that encode a protein of 612 amino acids.

The PGM3 gene is located on chromosome 6q14.1 and is composed of 18 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs and five distinct isoforms of this enzyme.

The PGM5 gene is located on chromosome 9q21.11 and is composed of 14 exons that encode a protein of 567 amino acids.

As mentioned above, the glycogen phosphorylase mediated release of glucose from glycogen yields a charged glucose residue (glucose-1-phosphate) without the need for hydrolysis of ATP. An additional necessity of releasing phosphorylated glucose from glycogen ensures that the glucose residues do not freely diffuse from the cell. In the case of muscle cells this is acutely apparent since the purpose in glycogenolysis in muscle cells is to generate substrate for glycolysis at a time in enhanced energy demand.

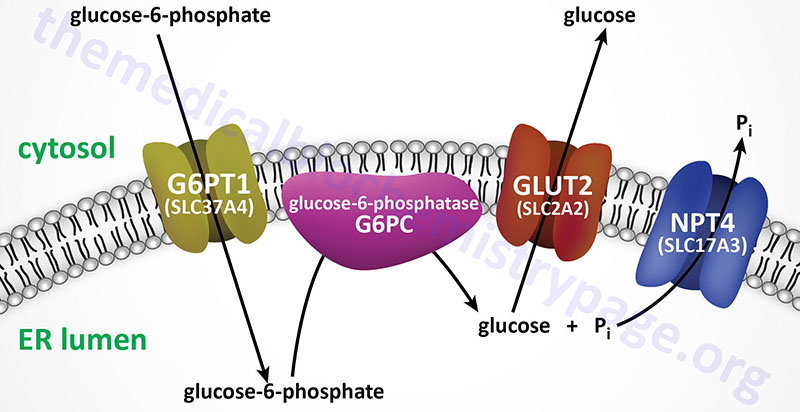

The conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to glucose occurs only in the liver, kidney, and small intestines via the action of glucose-6-phosphatase and does not occur in other tissues that synthesize glycogen (e.g. skeletal muscle and brain) as all other cells lack this enzyme. Therefore, any free glucose released from glycogen stores, through the action of the debranching enzyme, in skeletal muscle and brain will be oxidized in the glycolytic pathway. In the liver the action of glucose-6-phosphatase allows glycogenolysis to generate free glucose for maintaining blood glucose levels.

Glycogen Debranching

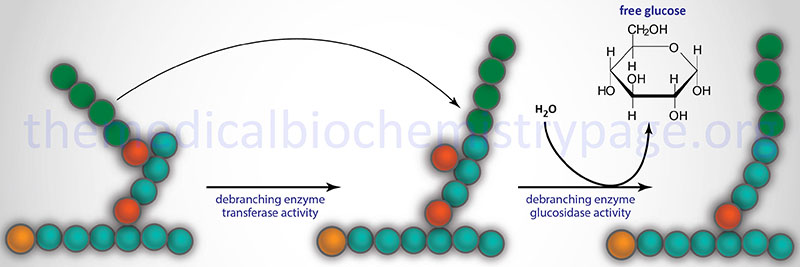

Glycogen phosphorylase cannot remove glucose residues from the branch points (α-1,6 linkages) in glycogen. The activity of phosphorylase ceases approximately four glucose residues from the branch point. The removal of the these branch point glucose residues requires the action of glycogen debranching enzyme (GDE). The official name of GDE is amylo-α-1,6-glucosidase, 4-α-glucanotransferase (gene symbol: AGL) which contains two activities: glucotransferase and glucosidase.

The AGL gene is located on chromosome 1p21.2 and is composed of 37 exons that generate five alternative spliced mRNAs that collectively encode two distinct isoforms (1 and 3) of the enzyme. Isoform 1 contains 1532 amino acids and isoform 3 contains 1516 amino acids.

The transferase activity of debranching enzyme removes the terminal three glucose residues of one branch and attaches them to a free C-4 end of a second branch. The glucose in α-(1,6)-linkage at the branch is then removed by the glucosidase activity of the debranching enzyme. This glucose residue is uncharged since the glucosidase-catalyzed reaction is not phosphorolytic. This means that theoretically glycogenolysis occurring in skeletal muscle could generate free glucose which could enter the blood stream. However, the activity of hexokinase in muscle is so high that any free glucose is immediately phosphorylated and enters the glycolytic pathway. Indeed, the precise reason for the temporary appearance of the free glucose from glycogen is the need of the skeletal muscle cell to generate energy from glucose oxidation, thereby, precluding any chance of the glucose entering the blood.

Lysosomal Glycogen Catabolism

When glycogen granules are not recruited for cytosolic degradation they become targets for increased phosphorylation making them less soluble which in turn induces their degradation via the lysosomal pathway. Lysosomal glycogen degradation is catalyzed by the enzyme lysosomal acid α-glucosidase (also called acid maltase) which is encoded by the GAA gene. The significance of this pathway for glycogen degradation is evidenced from the lethal disorder, Pompe disease, that is the result of mutations in the GAA gene.

The GAA gene is located on chromosome 17q25.3 and is composed of 21 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs, all of which encode the same 952 amino acid preproprotein.

Lysosomal glycogen is enriched in very large molecular weight granules. The pathway of lysosomal glycogen degradation represents 5% of total muscle glycogen and 10% of total liver glycogen degradation. One significant role for lysosomal glycogen degradation is in the neonate where liver lysosomal glycogen breakdown is the product of glycogen autophagy (referred to as glycophagy). This pathway for newborn glycogenolysis is most likely a mechanism for providing extra glucose-derived energy during and after birth.

The transport of glycogen to the lysosome involves interaction with the cargo-binding protein identified as starch binding domain containing protein 1 (encoded by the STBD1 gene). Expression of the STBD1 gene is highest in the liver and skeletal muscle, the two tissues with the highest levels of glucose storage as glycogen. Complexes of glycogen and STBD1 interact with the autophagy related gene 8 (ATG8) family member protein identified as GABARAPL1 (GABA type A receptor associated protein like 1).

The interaction with GABARAPL1 facilitates lysosomal uptake of glycogen molecules where the action of the GAA encoded hydrolase releases free glucose. The glucose is transported out of the lysosome via the GLUT1, GLUT2, and GLUT8 glucose transporters as well as the transporter encoded by the SPNS1 (SPNS lysolipid transporter 1, lysophospholipid) gene which has been shown to transport carbohydrate out of the lysosome. The acronym SPNS refers Drosophila spinster protein homolog. The SPNS1 encoded protein is a member of the large SLC family of transporters, like the GLUT transporters, and as such is also identified as SLC63A1.

Lysosomal glycogen breakdown, although catalyzed by α-glucosidase, also requires the action of the dual specificity phosphatase, laforin, and a second enzyme, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, encoded by the NHLRC1 gene (NHL repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1).

Laforin is encoded by the EPM2A (EPM2A glucan phosphatase) gene that is located on chromosome 6q24.3 and is composed of 15 exons that generate nine alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode six distinct protein isoforms. The EPM2 designation refers to Epilepsy, Progressive Myoclonus type 2.

The NHLRC1 gene is an intronless gene located on chromosome 6p22.3 that encodes a 395 amino acid protein. The NHLRC1 gene is also referred to as EPM2B.

The NHLRC1 encoded protein is called malin. The precise role for malin in the overall process of glycogen dephosphorylation is unclear but larforin-malin interaction is a required event for the process. The laforin-malin interaction is also involved in the regulation of the removal of glycogen-associated proteins not only via the autophagy–lysosomal pathway but also via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway.

Malin has been shown to ubiquitylate several glycogen-associated proteins including laforin, glycogen synthase, glycogen debranching enzyme, and the regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 which was originally referred to as protein targeting glycogen (PTG). PTG within skeletal muscle is encoded by the PPP1R3A (protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 3A) gene. Liver PTG is encoded by the PPP1R3B gene.

Mutations is either the EPM2A gene or the NHLRC1 gene are the cause of the lethal neurodegenerative disorder known as Lafora disease.

Glycogen Synthesis

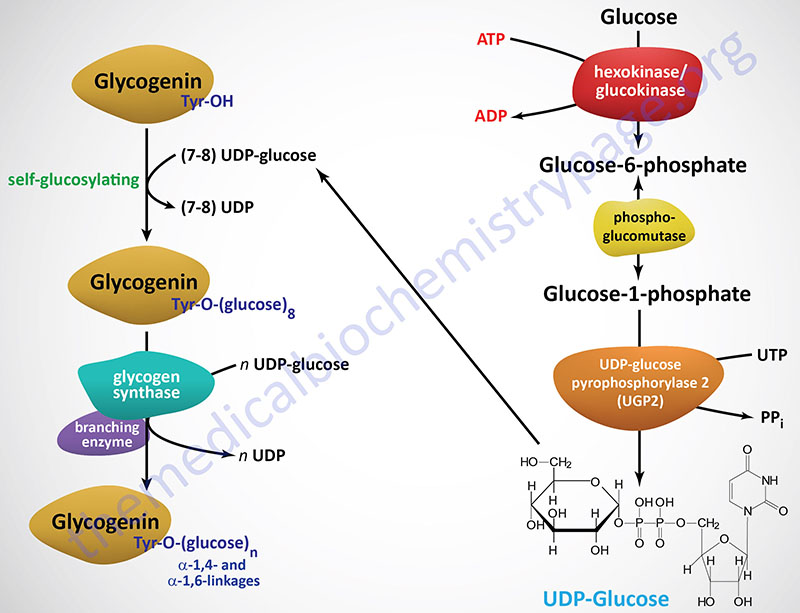

Glycogenin in de novo Glycogen Synthesis

For de novo glycogen synthesis to proceed the first few glucose residues are attached to a protein known as glycogenin. Glycogenin binds to actin filaments through a domain in the C-terminus of the protein. The interaction of glycogenin with actin filaments is required to initiate the synthesis of glycogen.

Glycogenin functions as a homodimer and catalyzes its own glycosylation, attaching C-1 of a UDP-glucose to a tyrosine residue (Y194) on the enzyme. This reaction is carried out by one subunit adding the glucose to the other subunit. Following the addition of the first glucose residue, each glycogenin subunit will then add a further 6-17 glucose residues in an intra-subunit reaction via α(1,4) glycosidic bonds. The attached glucose then serves as the primer required by glycogen synthase (GS) to attach additional glucose molecules via the mechanism described below.

Glycogenin binds to conserved amino acid sequences in the N-terminus of glycogen synthase. As the glycogen molecule grows on glycogenin, glycogen synthase is released from glycogenin and binds to the lengthening polymer via a glycogen-binding module in the C-terminus of the enzyme.

There are two glycogenin genes in humans identified as GYG1 and GYG2. The GYG1 gene is located on chromosome 3q24 and is composed of 10 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs. These three mRNAs produce three glycogenin-1 isoforms identified as isoform 1 (350 amino acids), isoform 2 (333 amino acids), and isoform 3 (279 amino acids). The GYG1 gene is predominantly expressed in muscle but is also expressed in many other tissues as well. Mutations in the GYG1 gene are associated with the recently (2010) characterized glycogen storage disease identified as type 15 (GSD15).

The GYG2 gene is located on chromosome Xp22.33 and is composed of 13 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a distinct glycogenin-2 isoform. Expression of the GYG2 gene is highest in adipose tissue with the next highest level, albeit at 10-fold less than adipose tissue, being in the liver.

Glycogen Synthase in Glycogen Synthesis

Like the action of glycogenin, glycogen synthase utilizes UDP-glucose as its substrate. Glycogen synthase add glucose residues from UDP-glucose to terminal glucose on glycogenein as well as to the non-reducing end glucose of a molecule of glycogen. The reaction catalyzed by glycogen synthase results in α(1,4) glycosidic linkage (non-branched) of the glucose residues.

The activation of glucose to be used for glycogen synthesis is carried out by the enzyme UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2. This enzyme exchanges the phosphate on C-1 of glucose-1-phosphate for UDP. The energy of the phosphoglycosyl bond of UDP-glucose is utilized by glycogen synthase to catalyze the incorporation of glucose into glycogen. UDP is subsequently released from the enzyme.

The human UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2 enzyme is encoded by the UGP2 gene. The UGP2 gene is located on chromosome 2p15 and is composed of 14 exons that generate eight alternatively spliced mRNAs. These eight mRNAs encode three different isoforms of the enzyme, isoform a (508 amino acids), isoform b (497 amino acids), and isoform c (388 amino acids).

There are two distinct glycogen synthase enzymes in humans. One is more widely expressed and predominates in skeletal muscle, the other predominates in the liver. The broadly expressed enzyme is encoded by the GYS1 gene and the liver, adipose tissue, heart, and pancreas enzyme is encoded by the GYS2 gene.

The GYS1 gene is located on chromosome 19q13.33 and is composed of 16 exons that produce two alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding two isoforms of the muscle enzyme. Isoform 1 is composed of 737 amino acids and isoform 2 is composed of 673 amino acids. Expression of the GYS1 gene is ubiquitous with the highest levels seen in the heart.

The GYS2 gene is located on chromosome 12p12.1 and is composed of 19 exons that produce a protein of 703 amino acids. The highest levels of expression of the GYS2 gene are seen in the liver and adipose tissue.

Glycogen Branching

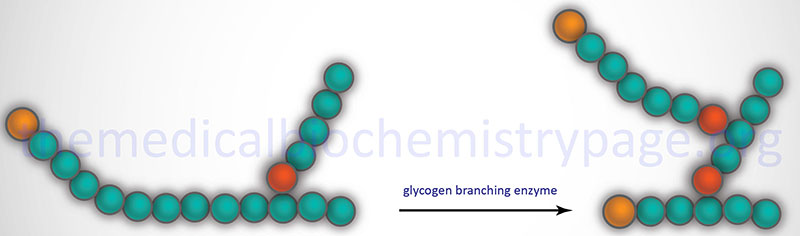

The α-1,6 branches in glycogen are produced by 1,4-α-glucan branching enzyme (also identified as amylo-(1,4 to 1,6)-transglucosidase) more commonly termed glycogen branching enzyme. Glycogen branching enzyme transfers a terminal fragment of 6-7 glucose residues (from a polymer at least 11 glucose residues long) to an internal glucose residue at the C-6 hydroxyl position.

Glycogen branching enzyme is encoded by the GBE1 gene. The GBE1 gene is located on chromosome 3p12.2 and is composed of 17 exons that encode a protein of 702 amino acids.

Glycogen Phosphorylation

Normal glycogen has small amounts of phosphate, as phosphomonoesters, at positions C2, C3, and C6 of the glucose residues in the molecule. Evidence has indicated that the phosphates on C2 and C3 are added by glycogen synthase but the precise mechanism for formation of the C6 phosphomonoesters remains elusive.

Removal of the phosphates from glycogen is catalyzed by the dual specificity phosphatase encoded by the EPM2A gene (EPM2A glucan phosphatase). The EPM2A of the gene name refers to Epilepsy, Progressive Myoclonus type 2A. The protein encoded by the EPM2A gene is called laforin (also known as laforin glycogen phosphatase) since loss of the enzyme is associated with the lethal neurodegenerative disease called Lafora disease. The level of phosphate in skeletal muscle glycogen is approximately 1 per 1,500 glucose residues. Laforin dephosphorylates glycogen and this dephosphorylation is required to facilitate the normal branching process.

The highly branched nature of glycogen maintains it water solubility. The consequences of loss-of-function of laforin is hyperphosphorylation of glycogen which renders it insoluble. The precipitation of hyperphosphorylated glycogen (histologically referred to as polyglucosan bodies, PBG or Lafora bodies), particularly in neurons, is the underlying cellular cause of the pathology of Lafora disease.

Brain Glycogen as a Regulator of Protein Glycosylation

Within the brain, glycogen serves a critical function as a storage molecule for not only glucose but also glucosamine that is required for protein N-glycosylation. Glucosamine has been shown to be covalently associated with glycogen, accounting for up to 25% of the sugar monomers of glycogen within the brain. The interaction of glycogen with glucosamine is facilitated by glycogen synthase, whereas the release of glucosamine from glycogen is facilitated by glycogen phosphorylase.

Glucosamine directly crosses the blood-brain barrier and accumulates in synaptosomes and ganglions where it is necessary for the production of gangliosides and glycoproteins. However, brain glucose is known as the primary molecule for the synthesis of glucosamine.

Polyglucosan bodies (PGB) are known to accumulate in the neurons of patients with Lafora disease but are also associated with the aging process and with dementia. Brain PGB have been shown to interact with lectins that are specific for the carbohydrates, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), galactose, and fucose. Contributing to pathology is the sequestration of glucosamine by PGB. This sequestration results in a decrease in the available pool of glucosamine that is required for the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc. The dysregulation of glycogen metabolism that is associated with the accumulation of PGB has been shown to be directly correlated to altered intracellular pools of glucosamine, UDP-GlcNAc, and the level of protein

N-glycosylation in the brain.

Regulation of Glycogen Catabolism

Consideration of the regulation of glycogen catabolism (glycogenolysis) involves tissue-specific differences in the the reasons for storing glucose as glycogen and the tissues-specific differences in the various forms of glycogen phosphorylase. Despite the tissue of expression, functional glycogen phosphorylase is a homodimeric enzyme that exist in two distinct conformational states: the T state (for tense, less active; referred to as phosphorylase b) and the R state (for relaxed, more active; referred to as phosphorylase a).

Phosphorylase is capable of binding to glycogen when the enzyme is in the R state (phosphorylase a). The skeletal muscle phosphorylase a conformation, but not liver phosphorylase, is enhanced by binding of AMP which serves as an allosteric activator. In liver and skeletal muscle the activity of the phosphorylase a conformation is inhibited by binding of the allosteric inhibitors, ATP and glucose-6-phosphate. Within hepatocytes glucose also acts as an allosteric inhibitor, an effect not exerted on skeletal muscle or brain phosphorylase.

Phosphorylase Kinase (PHK)

Glycogen phosphorylase is also subject to covalent modification by phosphorylation as a means of regulating its activity. The major site for this regulatory phosphorylation is Ser 14 on both subunits of the homodimeric enzyme. The basal activity of the unmodified phosphorylase enzyme (phosphorylase b) is sufficient to generate enough glucose-1-phosphate, for entry into glycolysis, for the production of sufficient ATP to maintain the normal resting activity of the cell. This is true in liver, brain, and skeletal muscle cells.

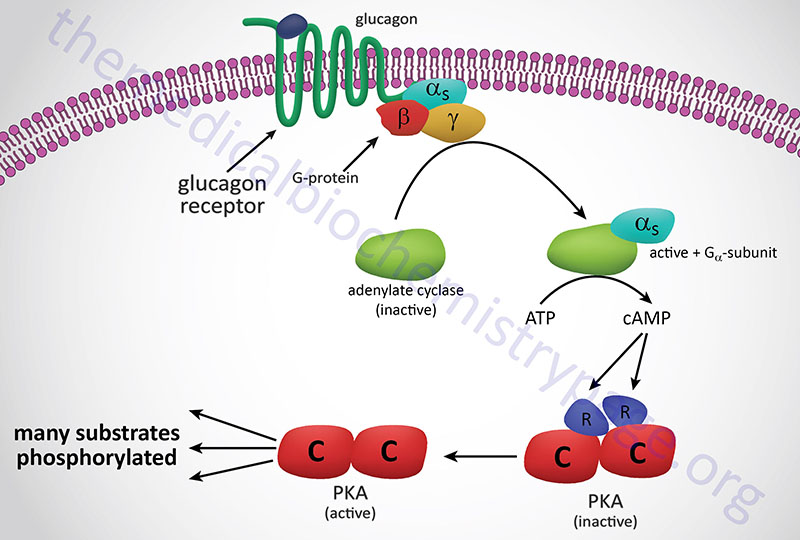

In response to lowered blood glucose the α cells of the pancreas secrete glucagon which binds to cell surface receptors that are predominantly found on hepatocytes. Glucagon receptors are also present on white adipocytes and cardiomyocytes but at significantly lower levels than those seen on hepatocytes. Because of this distribution of receptors, it is easy to understand why liver cells are the primary target for the action of glucagon.

The glucagon receptor is a Gs-coupled GPCR. The response of cells to the binding of glucagon to its cell surface receptor is, therefore, the activation of the enzyme adenylate cyclase. Activation of adenylate cyclase leads to a large increase in the formation of cAMP which then binds to, and activates the enzyme, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA: see Figure below). The original model of cAMP-mediated activation of PKA involved the binding of cAMP to the regulatory subunits of the enzyme leading to the release of the regulatory subunits and subsequent activation of the catalytic subunits. Recently it has been demonstrated that release of the regulatory subunits is not required for cAMP-mediated activation of PKA. When activated the catalytic subunits phosphorylate a number of target proteins on serine and threonine residues.

Of significance to this discussion is the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of phosphorylase kinase (PHK). There are three isoforms of phosphorylase kinase, one is primarily expressed in skeletal muscle, one primarily expressed in the liver, and one expressed primarily in the brain. All three isoforms of phosphorylase kinase are multi-subunit (hexadecameric) enzymes composed of four copies of each of the unique subunits: α, β, γ, and δ. The difference between the skeletal muscle (as well as heart), liver, and brain isoforms is the result of two distinct α proteins and two distinct γ proteins, each of which are encoded by different genes. The α and β subunits are the regulatory subunits that are phosphorylated. The γ subunit is the catalytic subunit. The δ subunit is calmodulin (described below) which can be encoded for by one of three calmodulin genes; CALM1, CALM2, CALM3.

The two different α subunits of phosphorylase kinase are encoded by the PHKA1 and PHKA2 genes. Although expression of the PHKA1 gene is not exclusive to muscle it is referred to as the muscle form. Likewise, although expression of the PHKA2 is not exclusive to the liver it is referred to as the liver form.

The PHKA1 gene is located on chromosome Xq13.1 and is composed of 33 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode three distinct protein isoforms. One of the PHKA1 isoforms (identified as α’) lacks an internal 59 amino acids, compared to the longest isoform. The α’ isoform predominates in cardiac myocytes and slow-twitch skeletal muscle cells.

The PHKA2 gene is located on chromosome Xp22.13 and is composed of 33 exons that encode a protein of 1235 amino acids.

The two different γ subunits are encoded by the PHKG1 and PHKG2 genes. Although expression of the PHKG1 gene is not exclusive to muscle it is referred to as the muscle form. Likewise, although expression of the PHKG2 gene is not exclusive to liver it is referred to as the liver form.

The PHKG1 gene is located on chromosome 7p11.2 and is composed of 12 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode three distinct protein isoforms.

The PHKG2 gene is located on chromosome 16p11.2 and is composed of 10 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs each of which encode a distinct protein: isoform 1 (406 amino acids) and isoform 2 (374 amino acids).

The common β subunit is encoded by the PHKB gene. The PHKB gene is located on chromosome 16q12.1 and is composed of 33 exons that undergo alternative splicing resulting in proteins with different internal segments of 28 amino acids and different N-termini. These differences are seen in the skeletal muscle β subunit which is distinct from the form expressed in the brain and several other tissues.

Mutations in the PHKA2 gene result in the X-linked liver glycogen storage diseases identified as types 9a1 and 9a2 (GSD9A1 and GSD9A2). Mutations in the PHKB gene result in the autosomal recessive liver and muscle glycogen storage disease identified as type 9B (GSD9B). Mutations in the PHKG2 gene cause the hepatic glycogen storage disease identified as type 9C (GSD9C). Mutations in the PHKA1 gene cause the X-linked muscle glycogen storage disease identified as type 9D (GSD9D). The various glycogen storage diseases are listed in the Table at the end of this page.

This identical cascade of events, responsible for the regulation of glycogen phosphorylase activity in hepatocytes, occurs in skeletal muscle cells and brain astrocytes as well. However, in skeletal muscle cells the induction of the cascade is the result of epinephrine binding to β2-adrenergic receptors on the surface of muscle cells or as a result of acetylcholine binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at a neuromuscular junction. Epinephrine is released from the adrenal glands in response to sympathetic nervous system outflow from the brain indicating an immediate need for enhanced glucose utilization in muscle, the so called fight-or-flight response.

Muscle cells lack glucagon receptors and therefore, do not respond in any way to pancreatic effects of low blood glucose. The presence of glucagon receptors on muscle cells would be futile anyway since the role of glucagon release is to increase blood glucose concentrations and muscle glycogen stores cannot contribute to blood glucose levels due to the high rates of glucose phosphorylation by hexokinase.

Regulation of phosphorylase kinase activity is also exerted by mechanisms involving Ca2+ ions. The ability of Ca2+ ions to regulate phosphorylase kinase is through the function of one of the subunits of this enzyme, specifically the γ subunit. The γ subunit of phosphorylase kinase is the ubiquitous protein, calmodulin. As indicated above, there are three different calmodulin genes, any one of which can encode the γ subunit of phosphorylase kinase.

Calmodulin is a calcium binding protein and the binding of Ca2+ induces a conformational change in calmodulin which in turn enhances the catalytic activity of phosphorylase kinase towards its substrate, phosphorylase b. This activity is crucial to the enhancement of glycogenolysis in muscle cells where muscle contraction is induced via acetylcholine stimulation at the neuromuscular junction.

The effect of acetylcholine release from nerve terminals at a neuromuscular junction is to depolarize the muscle cell leading to increased uptake of extracellular calcium via voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels and by release of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) stored Ca2+ via Ca2+-activation of calcium release channels (ryanodine receptors). The net effect of increased Ca2+ uptake and release from the SR is activation of muscle contractile activity as well as increased phosphorylase kinase activity. Thus, not only does the increased intracellular calcium increase the rate of muscle contraction it increases glycogenolysis which provides the muscle cell with the glucose it needs to oxidize to satisfy the increased ATP it needs for contraction.

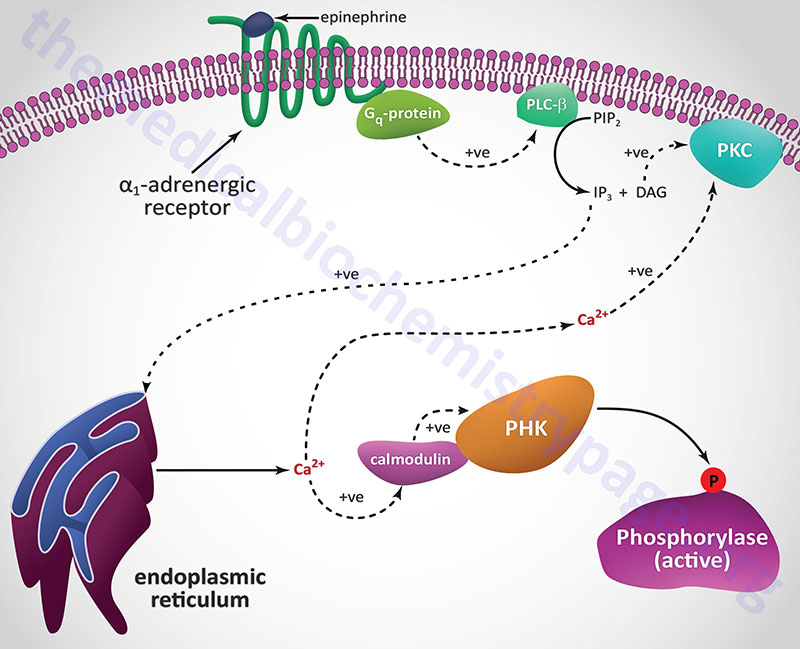

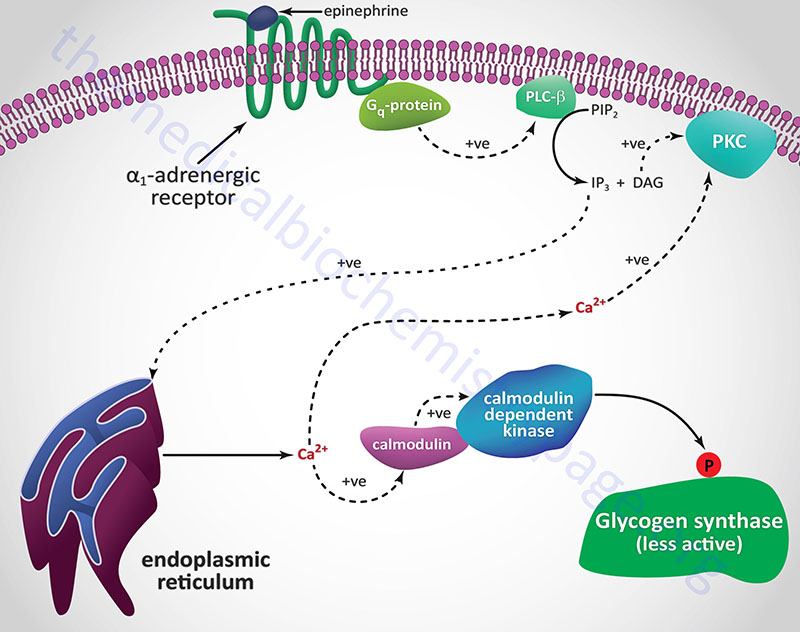

Another Ca2+ ion-mediated pathway to phosphorylase kinase activation is through activation of hepatic α1-adrenergic receptors by epinephrine as outlined in the following Figure.

Unlike β-adrenergic receptors, which are coupled to Gs-type G-proteins that activate adenylate cyclase, α1-adrenergic receptors are coupled through Gq-type G proteins that activate phospholipase-Cβ (PLCβ). However, it is important to note that α2-adrenergic receptors couple to a Gi-type G-protein and, as a result of ligand binding to this class of receptor, inhibit the activation of adenylate cyclase. Since hepatocytes express both β2– and α1-adrenergic receptors their responses to epinephrine during periods of fasting, as well as following sympathetic outflow from the brain, will be pronounced at the level of carbohydrate metabolism.

Activation of PLCβ leads to increased hydrolysis of membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2; PtdIns-4,5-P2), the products of which are inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3; Ins-1,4,5-P3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). DAG binds to and activates protein kinase C (PKC), an enzyme that phosphorylates numerous substrates, one of which is glycogen synthase (see below). IP3 binds to one of several receptors on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum leading to release of stored Ca2+ ions. The Ca2+ ions then interact with the calmodulin subunits of phosphorylase kinase resulting in its activation. Additionally, the Ca2+ ions activate PKC in conjunction with DAG.

Humans express three distinct IP3 receptors encoded by the ITPR1, ITPR2, and ITPR3 genes.

The ITPR1 gene which is located on chromosome 3p26.1 and is composed of 62 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding four distinct isoforms of the receptor. ITPR1 isoform 1 is a 2710 amino acid protein, isoform 2 is a 2695 amino acid protein, isoform 3 is a 2743 amino acid protein, and isoform 4 is a 2758 amino acid protein.

The ITPR2 gene is located on chromosome 12p11.23 and is composed of 62 exons that encode a 2701 amino acid protein. Expression of the ITPR2 gene is highest in the liver and kidney.

The ITPR3 gene is located on chromosome 6p21.31 and is composed of 62 exons that encode a 2671 amino acid protein. The highest levels of expression of the ITPR3 gene are found in the gastrointestinal system.

Each of the IP3 receptors possesses a cytoplasmic N-terminal ligand-binding domain and is comprised of six membrane-spanning helices that forms the core of the ion pore.

Reversal of Phosphorylation-Mediated Effects on Glycogenolysis

In order to terminate the activity of the enzymes of the glycogen phosphorylase activation cascade, once the needs of the body are met, the modified enzymes need to be unmodified. In the case of Ca2+ induced activation, the level of Ca2+ ion release from muscle stores will terminate when the incoming nerve impulses cease.

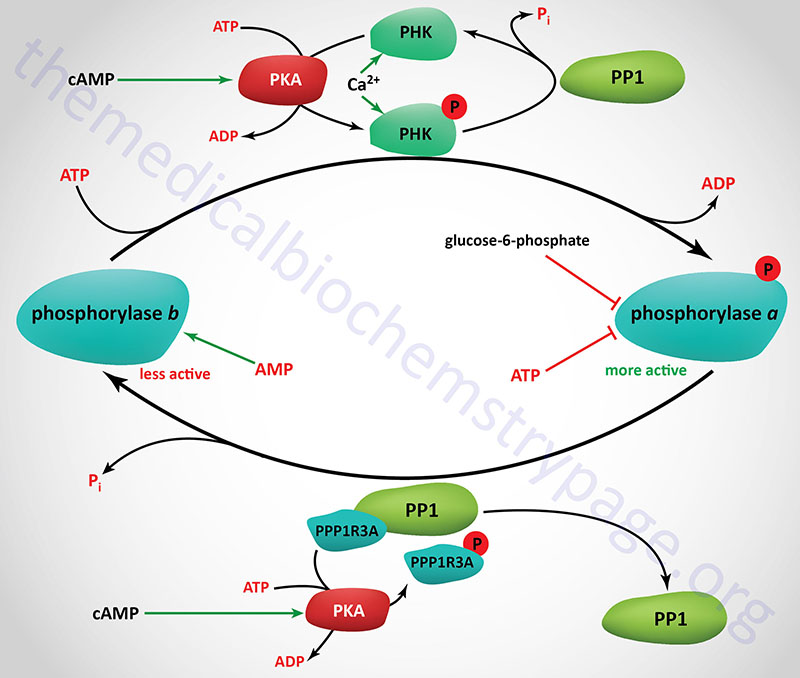

The removal of the phosphates on phosphorylase kinase and phosphorylase a is carried out by a family of enzymes identified as phosphoprotein phosphatase-1 (PP1). Each functional PP1 is a heterodimeric enzyme composed of a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit. Humans express three distinct PP1 catalytic subunit genes identified as PPP1CA, PPP1CB, and PPP1CC.

There are at least 29 PP1 regulatory subunit genes expressed in the human genome. Several of the regulatory subunits are also involved in targeting of PP1 to glycogen. These regulatory subunits are also commonly referred to as protein targeting to glycogen, PTG (see Figure below).

The PTG regulator of the muscle isoform of PP1 is encoded by the protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 3A (PPP1R3A) gene. The PPP1R3A gene is located on chromosome 7q31.1 and is composed of 5 exons that encode a 1122 amino acid protein. The muscle PTG protein is also commonly referred to as PP1G.

The PTG regulator of the liver form of PP1 is encoded by the PPP1R3B gene. The PPP1R3B gene is located on chromosome 8p23.1 and is composed of 3 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encoded the same 285 amino acid protein. The PPP1R3B encoded protein was the originally identified PTG activity.

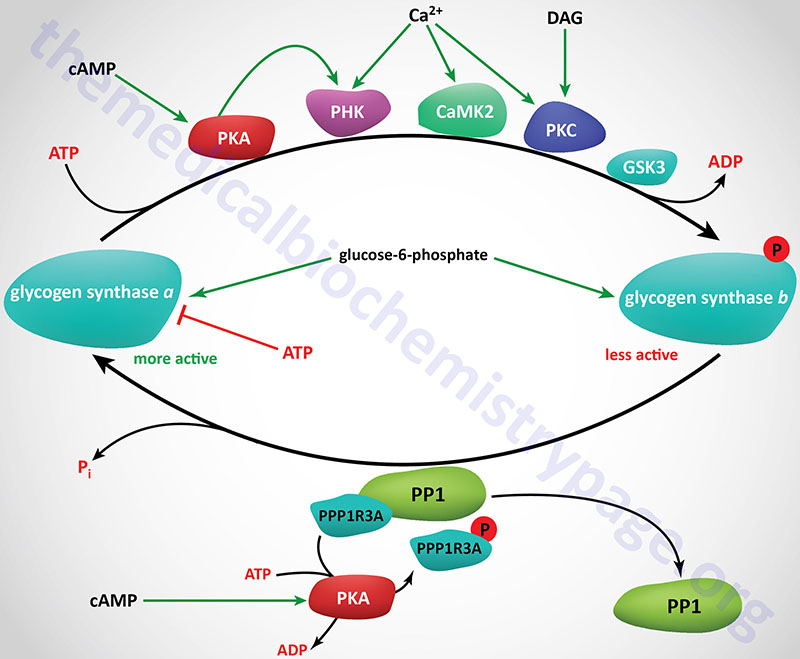

In order that the phosphate residues placed on various enzymes by PKA and phosphorylase kinase (PHK) are not immediately removed, the activity of PP1 must also be regulated. Within skeletal muscle this is accomplished through the interaction of PP1 catalytic subunits with the regulatory subunits encoded by the PPP1R3A gene (the PTG protein). Since the protein encoded by this gene inhibits the activity of PP1 it was once called phosphoprotein phosphatase inhibitor 1 (PPI-1) or PP1 inhibitor. The PPP1R3A encoded protein (PTG) is phosphorylated by PKA on Ser65 which causes PP1 to dissociate from the PTG complex, thereby preventing glycogen synthase from being dephosphorylated keeping it in the less active state. Conversely, insulin mediated signaling results in phosphorylation of the PPP1R3A protein at Ser46 which results in increased activity of PP1, removal of the inhibitory phosphate from glycogen synthase and a subsequent increase in glycogen synthesis.

Regulation of Glycogen Synthesis

Glycogen synthase is a tetrameric enzyme consisting of four identical subunits. The liver and muscle glycogen synthase proteins are derived from different genes and share only 46% amino acid identity. As indicated above, the liver glycogen synthase is encoded by the GYS2 gene while the muscle form (as well as that expressed in several other tissues) is encoded by the GYS1 gene. Regardless of tissue of expression, the activity of glycogen synthase is regulated by both allosteric effectors and by phosphorylation of serine residues in the subunit proteins.

Allosteric regulation of glycogen synthase activity is effected by glucose-6-phosphate and ATP with glucose-6-phosphate being a positive effector and ATP being and inhibitory effector.

Phosphorylation of Glycogen Synthase

Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase has been shown to occur on at least nine different serine residues and these phosphorylation events are carried out by numerous different kinases. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase reduces its activity towards UDP-glucose. When in the phosphorylated state, glycogen synthase inhibition can be overcome by the presence of the allosteric activator, glucose-6-phosphate. The two forms of glycogen synthase are identified by the same nomenclature as used for glycogen phosphorylase. The unphosphorylated and most active form is termed glycogen synthase a and the phosphorylated, less active form is termed glycogen synthase b.

Numerous kinases have been shown to phosphorylate and regulate both hepatic and muscle forms of glycogen synthase. Most detailed analyses of glycogen synthase phosphorylation have been carried out using enzyme isolated from skeletal muscle but related findings with liver glycogen synthase have also been demonstrated.

At least nine sites of phosphorylation have been identified in glycogen synthase and these nine sites are clustered into four phosphorylation domains present in the N-terminal and C-terminal ends of the enzyme. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase occurs through the activities of at least ten distinct kinases. The phosphorylation sites in glycogen synthase are identified as site 1a, 1b, 2, 2a, 3a, 3b, 3c, 4, and 5. Sites 2, 2a, 3a, and 3b are the most significant with respect to the regulation of the activity of glycogen synthase.

Regulation of glycogen synthase by phosphorylation occurs via both primary and secondary phosphorylation events. The ten kinases that regulate glycogen synthase activity are PKA, PKC, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (encoded by the GSK3B gene), phosphorylase kinase (PHK), a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 family member kinase (CAMK2 or CAMKII), a member of the casein kinase 1 (CK1) family, casein kinase 2 (CK2), AMPK, PAS domain containing serine/threonine kinase (PASK), dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation regulated kinase 2 (DYRK2), and p38MAPK (encoded by the MAPK14 gene).

Primary phosphorylation events regulating muscle glycogen phosphorylase activity are initiated by PKA, PKC, CAMKII, PHK, and CK2. Secondary phosphorylation events are the result of GSK3β and CK1.

The CK1 family of kinases is composed of seven monomeric enzymes.

Recent studies demonstrate that the association of AMPK and PHK with the liver form of glycogen synthase is not significant or does not occur.

Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3: GSK3

Humans express two genes encoding glycogen synthase kinase 3 enzymes, GSK3A (encoding GSK3α) and GSK3B (encoding GSK3β). The GSK3β isoform is the more well characterized enzyme and its activities and regulation are briefly outlined in this section. GSK3β functions in several subcellular compartments including the cytosol, nucleus, and the mitochondria. GSK3β also interacts with numerous receptor-coupled signaling proteins as well as several G-protein coupled receptors, GPCR.

The GSK3A gene is located on chromosome 19q13.2 and is composed of 11 exons that encode a 483 amino acid protein.

The GSK3B gene is located on chromosome 3q13.33 and is composed of 12 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode distinct protein isoforms. Isoform 1 encodes the longest GSK3β protein at 433 amino acids.

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is a unique kinase in that it is constitutively active and its activity is inhibited by the signal transduction cascade activated by the insulin receptor as well as by the Wnt signaling pathway. In addition to Ser/Thr kinase activity, GSK3 is capable of phosphorylating Tyr (Y) residues and does so by autophosphorylating the tyrosine residue at position 216 (Y216) while the enzyme is being translated. The phosphorylation of Y216 is required for maximal GSK3β activity.

GSK3β has been shown to phosphorylate over 100 different substrates and thus plays critical regulatory roles in multiple pathways beyond just the regulation of glycogen metabolism. A unique feature of GSK3 is that the majority of its substrates are pre-phosphorylated at a Ser or Thr residue four amino acids C-terminal to the Ser or Thr residue that GSK3β phosphorylates.

The activity of GSK3β is regulated by phosphorylation of the enzyme. Phosphorylation of GSK3β on Ser-9 (S9) results in the binding of pre-phosphorylated substrates, thus blocking GSK3β activity. The phosphorylation of S9 generates a pseudo-substrate within the N-terminal tail of GSK3β that then interacts with the primed substrate binding pocket of the enzyme which reduces the ability of primed substrates to bind and be phosphorylated by GSK3β. Kinases that are known to phosphorylate S9 in GSK3β are AKT/PKB, PKA, PKC, and p70S6K, although these are not the only kinases capable of phosphorylating GSK3β. The equivalent site in GSK3α is S21.

GSK3β is able to activate PP1 by phosphorylating, and thereby inhibiting, the activity of the PP1 inhibitor. This action of GSK3β results in de-phosphorylation of upstream kinases which in turn reduces the ability of these kinases to carry out S9 phosphorylation of GSK3β.

GSK3β substrates that are not primed by pre-phosphorylation contain an acidic residue that replaces the primed phosphorylated Ser or Thr residue that is found in other substrates. Phosphorylation of these non-primed substrates is not inhibited by the S9 phosphorylation of GSK3β.

Nuclear localization of GSK3β occurs through the presence of a nuclear localization sequence in the enzyme. Within the nucleus GSK3β regulates gene expression, primarily via the phosphorylation of numerous transcription factors. Indeed, transcription factors represent the largest class of GSK3β substrates. Several transcription factor substrates of GSK3β include p53, C/EBP (for CCAAT-box/Enhancer Binding Protein), CREB (cAMP response-element binding protein), MYC, NFκB, and signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3).

GSK3β action in the nucleus has also been shown to regulate epigenetic processes. GSK3β has been shown to phosphorylate several histone deacetylases (HDAC) as well as several histone acetyltransferases (HAT).

Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II: CAMKII

There are two broad classes of kinase families that are regulated by interaction with complexes of Ca2+ and the regulatory protein, calmodulin (CaM), defined as Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases (CaMK).

One family of CaMK have restricted substrate specificity such as that of phosphorylase kinase (PHK). There are two additional restricted substrate specificity CaMK; elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF2K), and myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). Elongation factor 2 kinase was also identified as CaMKIII.

The other family of CaMK is the multifunctional CaMK family. This family contains four subfamilies identified as CaMKK, CaMKI, CaMKII, and CaMKIV.

The CaMKK family is composed of two members encoded by the CAMKK1 and CAMKK2 genes. These two genes encode the CaMKKα and CaMKKβ kinases, respectively.

The CaMKI family is composed of four members encoded by the CAMK1, PNCK, CAMK1G, and CAMK1D genes. These genes encode the CaMKIα, CaMKIβ, CaMKIγ, and CaMKIδ kinases respectively. The PNCK gene is Pregnancy up-regulated Non-ubiquitous CaM Kinase.

The CaMKIV family is composed of a single enzyme which is encoded by the CAMK4 gene.

There are four genes encoding CaMKII enzymes, identified as the CAMK2A, CAMK2B, CAMK2D, and CAMK2G genes. These genes encode the CaMKIIα, CaMKIIβ, CaMKIIδ, and CaMKIIγ isoforms, respectively. CaMKIIα and CaMKIIβ are primarily found in nervous tissues while CaMKIIδ and CaMKIIγ are found at low levels in virtually all tissues but predominate in cardiac tissues.

The different CaMKII isoforms can interact to form various heteromeric holoenzymes such that at least 28 different holoenzyme forms have been identified. These different holoenzymes have differing affinities for calmodulin. Most CaMKII holoenzymes are dodecameric consisting of two hexameric rings of subunits. The catalytic domain of CaMKII enzymes resides in the N-terminus and there is a regulatory domain residing in the middle of the protein. The regulatory domain functions to autoinhibit the catalytic domain.

The binding of Ca2+/CaM complexes to the CaMKII enzymes results in the activation of autophosphorylation of a Thr residue (T287) in each of the monomers. The Thr autophosphorylation enhances CaM binding, even under low Ca2+ conditions, and results in activation of the kinase activity of the enzyme.

Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase by CaMKII occurs at sites 1b and 2.

Glucagon Effects on Glycogen Synthase

When glucagon binds its receptor on hepatocytes the resultant rise in activity of PKA leads to increased phosphorylation of glycogen synthase directly by PKA. The regulatory phosphorylation sites in glycogen synthase targeted by PKA are 1a, 1b, and 2. Within liver, phosphorylation of site 2 in glycogen phosphorylase has been shown to be the most significant relative to its regulation.

Activated PKA also leads to phosphorylation and activation of phosphorylase kinase (PHK) which also phosphorylates glycogen synthase on site 2. In addition, glucagon signaling results in an increase in the activity of CK2. Thus, the net effect of glucagon action on hepatocytes is activation of three distinct kinases that phosphorylate and inhibit glycogen synthase.

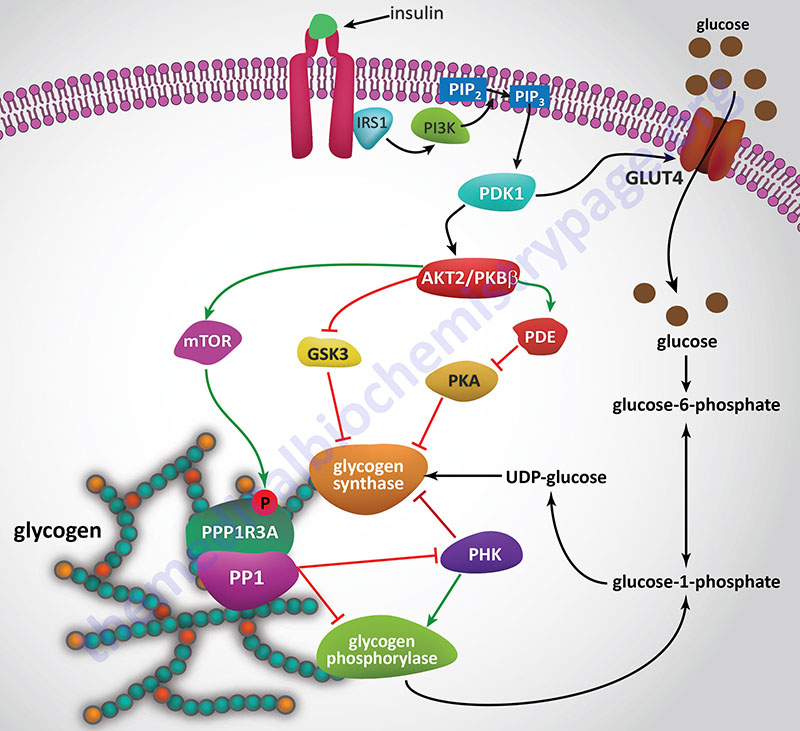

Insulin Effects on Glycogen Synthase

Since insulin and glucagon are counter-regulatory hormones it should be clear that they will exert opposing effects on the rate and level of glycogen synthase phosphorylation. As described above, when glucagon binds its receptor on hepatocytes there is a resultant rise in cAMP and a concomitant increase in the activity of PKA. The action of insulin, at the level of PKA, is to increase the activity of phosphodiesterase which hydrolyzes cAMP to AMP thereby reducing the level of active PKA.

Insulin also exerts a negative effect on the activity of GSK3 such that there is a reduced level of phosphorylation of glycogen synthase by this kinase. Within skeletal muscle GSK3 phosphorylates sites 3a, 3b, 3c, and 4 in glycogen synthase. To see more on the action of insulin at the level of GSK3 visit the Insulin Function, Insulin Resistance, and Food Intake Control of Secretion page.

Catecholamine Effects on Glycogen Synthase

Hormones and neurotransmitters that result in release of stored intracellular Ca2+ also lead to negative regulation of glycogen synthase activity. As described above, Ca2+ ions bind to the calmodulin subunit of phosphorylase kinase (PHK) and result in its activation leading to increased phosphorylation and inhibition of glycogen synthase.

When α1-adrenergic receptors are stimulated there is an increase in the activity of PLCβ with a resultant increase in PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; PtdIns-4,5-P2) hydrolysis. The products of PIP2 hydrolysis are DAG and IP3 (inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate; Ins-1,4,5-P3). As described above for glycogen phosphorylase, DAG, along with the Ca2+ ions released by IP3, activate PKC which phosphorylates and inactivates glycogen synthase. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase by PKC occurs in the same domain of the enzyme that is one of the target sites for PKA phosphorylation, namely site 2.

The net effects of the various phosphorylations of glycogen synthase result in:

- decreased affinity of the enzyme for UDP-glucose.

- decreased affinity of the enzyme for glucose-6-phosphate.

- increased affinity of the enzyme for ATP and Pi.

Dephosphorylation of Glycogen Synthase

Reconversion of glycogen synthase b to glycogen synthase a requires dephosphorylation. This is carried out predominately by the serine/threonine phosphatase described earlier, PP1. This, of course is the same phosphatase involved in the dephosphorylation of glycogen phosphorylase described in detail above. Although another serine/threonine phosphatase, namely protein phosphatase-2A (PP2A), has been shown to dephosphorylate glycogen synthase in vitro, its role in vivo is significantly less than that of PP1.

The activity of PP1 is also affected by insulin in an opposing way to the effects of glucagon and epinephrine. This should appear obvious since the role of insulin is to increase the uptake of glucose from the blood and to store it as glycogen.

Nuclear Glycogen Metabolism and Control of Gene Expression

Although the cytosol is the principal site of glycogen accumulation, the molecule is also found in the nucleus, in the mitochondria, and associated with the endoplasmic reticulum, ER (or the sarcoplasmic reticulum in muscle). The presence of glycogen in the nucleus suggests that there is likely to be a nuclear specific glycogen metabolic pathway(s).

There is no known mechanism for transporting glycogen across cell membranes and given that glycogen synthase has been found in the nucleus, it has been proposed that glycogen synthesis is likely to occur de novo in the nucleus. In addition to glycogen synthase (encoded by the GYS1 and GYS2 genes), UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2 (encoded by the UGP2 gene), and the glucose-6-phosphate transporter, G6PT1 (encoded by the SLC37A4 gene) have been found in the nucleus. Evidence has shown that glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) is the substrate for incorporation of glucose into nuclear glycogen.

In addition to enzymes of glycogen metabolism, all the glycolytic enzymes (excluding hexokinase) and the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) are also found in the nucleus. Indeed, nuclear PDHc regulates histone acetylation.

One of the major functions of nuclear glycogen is to serve as a carbon pool supplying the metabolic substrates for histone modification that is independent of cytoplasmic metabolites of glycogen and glucose. Nuclei have been shown to metabolize glucose-6-phosphate to the glycolytic intermediates, including fructose-6-phosphate (F6P), 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG), and pyruvate. However, nuclei do not convert free glucose to glycolytic intermediates.

Metabolism of nuclear glycogen is enhanced by the presence of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, malin [encoded by the NHLRC1 (NHL repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1) gene], and requires the presence of glycogen phosphorylase. One important function for nuclear glycogen metabolism is most likely to be the generation of nuclear localized pyruvate which can then serve as a source of the nuclear acetate required for histone acetylation.

In in vitro experiments, where malin is overexpressed, it was found that there was increased protein acetylation in the nucleus and that this required the presence of glycogen phosphorylase. Malin overexpressing cells have increased acetylation of numerous histones including H1.4, H2A1, H2A3, H3, and H4. Histone acetylation is directly associated with changes in transcription. Indeed, in malin overexpressing cells increased expression of genes involved in pathways of smooth muscle contraction, DNA methylation, DNA demethylation, and DNA alkylation has been documented while decreased expression of genes involved in chromosome segregation, cell proliferation, and cellular catabolic processes were also found.

Nuclear glycogenolysis contributes to the pyruvate pool and subsequently to histone acetylation. This process is significant not only for normal cells but is also contributory to the genesis of many types of cancer. Cancers that have reduced expression of the NHLRC1 gene show downregulation of glycogenolysis due to the role of malin in nuclear localized glycogen phosphorylase. The reduction in nuclear glycogen metabolism leads to a lack of substrate for histone acetylation and contributes to the altered epigenetic landscape seen in many cancers.

Clinical Consequences of Defects in Glycogen Homeostasis

Glycogen Storage Diseases

Since glycogen molecules can become enormously large, an inability to degrade glycogen can cause cells to become pathologically engorged; it can also lead to the functional loss of glycogen as a source of cell energy and as a blood glucose buffer. Although glycogen storage diseases are quite rare, their effects can be most dramatic. The debilitating effect of many glycogen storage diseases depends on the severity of the mutation causing the deficiency. In addition, although the glycogen storage diseases are attributed to specific enzyme deficiencies, other events can cause the same characteristic symptoms.

For example, Type 1 glycogen storage disease (von Gierke disease) is attributed to lack of glucose-6-phosphatase. However, the catalytic activity of this enzyme is localized to a domain of the membrane-localized enzyme present in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER); in order to gain access to the phosphatase, glucose-6-phosphate must pass through a specific translocase in the ER membrane (see Figure below). Mutation of either the phosphatase or the translocase makes transfer of liver glycogen to the blood a very limited process. Thus, mutation of either gene leads to symptoms associated with von Gierke disease, which occurs at a rate of about 1 in 200,000 people.

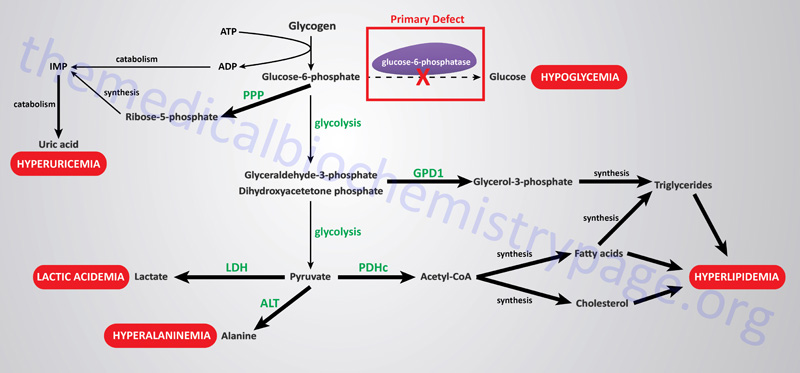

The metabolic consequences of the hepatic glucose-6-phosphate deficiency of von Gierke disease extend well beyond just the obvious hypoglycemia that results from the deficiency in liver being able to deliver free glucose to the blood. The inability to release the phosphate from glucose-6-phosphate results in diversion into glycolysis and production of pyruvate as well as increased diversion onto the pentose phosphate pathway.

The production of excess pyruvate, at levels above of the capacity of the TCA cycle to completely oxidize it, results in its reduction to lactate resulting in lactic acidemia. In addition, some of the pyruvate is transaminated to alanine leading to hyperalaninemia.

Some of the pyruvate will be oxidized to acetyl-CoA which can’t be fully oxidized in the TCA cycle and so the acetyl-CoA will end up in the cytosol following conversion to citrate via the action of the TCA cycle enzyme, citrate synthase. Following transport to the cytosol the cytosolic enzyme, ATP-citrate lyase, hydrolyzes the citrate to oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA. Once in the cytosol the acetyl-CoA can serve as a substrate for fatty acid synthesis and ultimately triglyceride synthesis, as well as cholesterol synthesis, resulting in hyperlipidemia.

The oxidation of glucose-6-phosphate via the pentose phosphate pathway leads to increased production of ribose-5-phosphate which then activates the de novo synthesis of the purine nucleotides. In excess of the need, these purine nucleotides will ultimately be catabolized to uric acid resulting in hyperuricemia and consequent symptoms of gout.

The interrelationships of these metabolic pathways is diagrammed in the Figure below.

The glycogen storage diseases are divided into two primary categories: those that result principally from defects in liver glycogen homeostasis and those that represent defects in muscle glycogen homeostasis. The liver glycogen storage diseases result in hepatomegaly and hypoglycemia or cirrhosis, whereas the muscle glycogen storage diseases result in skeletal and cardiac myopathies and/or energy impairment. Historical nomenclature for the glycogen storage diseases utilized Roman numerals but they are also often denoted with cardinal numbers. One of the most notable muscle glycogen storage diseases is Pompe disease (GSDII or GSD2) due to it being featured in the movie “Extraordinary Measures”.

Several glycogenoses are the result of deficiencies in enzymes of glycolysis whose symptoms and signs are similar to those seen in McArdle disease (GSD5 or GSDV). These include deficiencies in muscle phosphoglycerate kinase and muscle pyruvate kinase as well as deficiencies in fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase and phosphoglycerate mutase.

Table of Glycogen Storage Diseases

| Type: Name | Enzyme Affected | Gene | Primary Organ | Manifestations /Comments |

| GSD0A | liver isozyme of glycogen synthase | GYS2 | liver | hypoglycemia, early death, hyperketonemia, low blood lactate and alanine; first described in 1963 by G.M. Lewis thus often referred to as Lewis disease |

| GSD0B | muscle isozyme of glycogen synthase | GYS1 | muscle | cardiomyopathy, exercise intolerance; characteristic features identified in autopsy in children who died suddenly following exercise |

| GSD1a von Gierke | glucose-6-phosphatase | G6PC | liver | hepatomegaly, severe fasting hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, kidney failure (Fanconi syndrome), thrombocyte dysfunction |

| GSD1b | microsomal glucose-6-phosphate transporter (G6PT1): this protein is a member of the solute carrier protein family and the gene is identified as SLC37A4 | SLC37A4 | liver | like 1a, but also associated with neutropenia and increased susceptibility to bacterial infections |

| GSD2 Pompe | lysosomal acid α-glucosidase also called acid maltase | GAA | skeletal and cardiac muscle | infantile form (25% of cases) results in death by age 2, defined as infantile-onset Pompe disease (IOPD); juvenile form associated with myopathy; adult form is a muscular dystrophy-like form; non-infantile onset forms identified as late-onset Pompe disease (LOPD); a Pompe-like disease, once identified as GSD2B, results from mutations in the LAMP2 (lysosome-associated membrane protein 2) gene and is correctly identified as Danon disease |

| GSD3 Cori or Forbes | glycogen debranching enzyme | AGL | liver, skeletal and cardiac muscle | infant hepatomegaly, myopathy |

| GSD4 Andersen | glycogen branching enzyme | GBE1 | liver, muscle | infantile hypotonia, hepatosplenomegaly, cirrhosis |

| GSD5 McArdle | muscle phosphorylase | PYGM | skeletal muscle | exercise-induced cramps and pain, myoglobinuria |

| GSD6: Hers | liver phosphorylase | PYGL | liver | hepatomegaly, mild fasting hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia and ketosis, improvement with age |

| GSD7: Tarui | muscle-specific subunit of PFK-1 | PKFM | muscle, RBC | similar to GSD5, also hemolytic anemia |

| GSD9A1/A2 | α subunit of hepatic phosphorylase kinase | PHKA2 | liver | mildest form of GSD, hepatomegaly, growth impairment, elevated plasma AST and ALT, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, fasting hyperketosis; was identified at one time as GSD8 (GSDVIII) |

| GSD9B | common β subunit of phosphorylase kinase | PHKB | liver and muscle | marked hepatomegaly in early childhood, fasting hypoglycemia |

| GSD9C | γ subunit hepatic phosphorylase kinase | PHKG2 | liver | increased glycogen in muscle as well as liver, hepatosplenomegaly, short stature, hypoglycemia, muscle weakness |

| GSD9D | α subunit muscle phosphorylase kinase | PHKA1 | muscle | nighttime muscle cramping in childhood, late-onset exercise-induced muscle fatigue and cramping |

| GSD10 | phosphoglycerate mutase | PGAM2 | muscle | exercise-induced cramps, occasional myoglobinuria, exercise intolerance |

| GSD11 | muscle-specific subunit of lactate dehydrogenase | LDHA | muscle | exercise-induced myoglobinuria, easily fatigued |

| Fanconi-Bickel (hepatorenal glycogenosis with renal Fanconi syndrome) | glucose transporter-2 (GLUT-2) | SLC2A2 | liver | was originally referred to as GSD11 but term no longer valid for this disease; is a GSD secondarily related to nonfunctional glucose transport; failure to thrive, hepatomegaly, rickets, proximal renal tubular dysfunction; also associated with a form of permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus |

| GSD12 | aldolase A | ALDOA | liver, RBC | hepatosplenomegaly, non-spherocytic hemolytic anemia |

| GSD13 | muscle predominant form of enolase: β-enolase | ENO3 | muscle | myalgia, exercise intolerance |

| CDG1T (once called GSD14) | predominant form of phosphoglucomutase | PGM1 | multiple affected tissues | this disease is a type 1 congenital disorder of glycosylation; associated with cleft lip, bifid uvula, short stature, hepatomegaly, hypoglycemia, exercise intolerance |

| GSD15 | muscle predominant form of glycogenin | GYG1 | muscle | muscle weakness, glycogen accumulation in heart, cardiac arrhythmias |

Lafora Disease

Lafora disease is a fatal autosomal recessive disease that is the result of a defect in glycogen metabolism. The disease gets its name from the Spanish neuropathologist, Gonzalo Rodriguez Lafora, who initially characterized the disorder. Lafora disease is characterized by the presence of inclusion bodies (the composition of which is glycogen), called Lafora bodies, in the cytoplasm of the cells of numerous tissues including neurons, heart, skeletal muscle, and liver.

Lafora disease is caused by loss-of-function mutations in either of two genes. One gene (EPM2A) encodes the EPM2A glucan (glycogen) phosphatase, which is commonly called laforin. The other gene (NHLRC1) encodes the NHL repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1, which is commonly called malin. The NHLRC1 gene was also known as EPM2B.

Laforin is a dual specificity phosphatase that removes phosphate from glycogen. The lack of laforin activity in Lafora disease leads to hyperphosphorylation of glycogen. Hyperphosphorylated glycogen disrupts the processes of branching and debranching leading to longer glucose chains than in a normal glycogen molecule. These abnormal glycogens (called polyglucans) are insoluble and ultimately lead to the formation of Lafora bodies. Normal laforin functions to maintain the low level of phosphomonoesters in glycogen which prevents the molecule from precipitating. As its gene name implies, malin is a ubiquitin ligase whose precise function in the process of glycogen dephosphorylation is incompletely understood. However, evidence indicates that malin ubiquitylates several enzymes in glycogen homeostasis in a laforin-dependent manner. Together laforin and malin interact to regulate glycogen phosphorylation and chain length pattern, the latter of which is crucial to the solubility of glycogen in the cell.