Last Updated: December 16, 2025

Glycosaminoglycans

The most abundant heteropolysaccharides in the body are the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). The glycosaminoglycans are historically referred to as the mucopolysaccharides given that they were originally characterized in mucus membranes and mucosal exudates. The GAG molecules are long unbranched polysaccharides containing a repeating disaccharide unit. The disaccharide units contain either of two modified sugars, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) or N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), and a uronic acid such as glucuronate (GlcA) or iduronate (IdoA) or a galactose residue. GAGs are highly negatively charged molecules, with extended conformation that imparts high viscosity to the solution in which they reside. GAGs are located primarily on the surface of cells or in the extracellular matrix (ECM) but are also found in secretory vesicles in some types of cells.

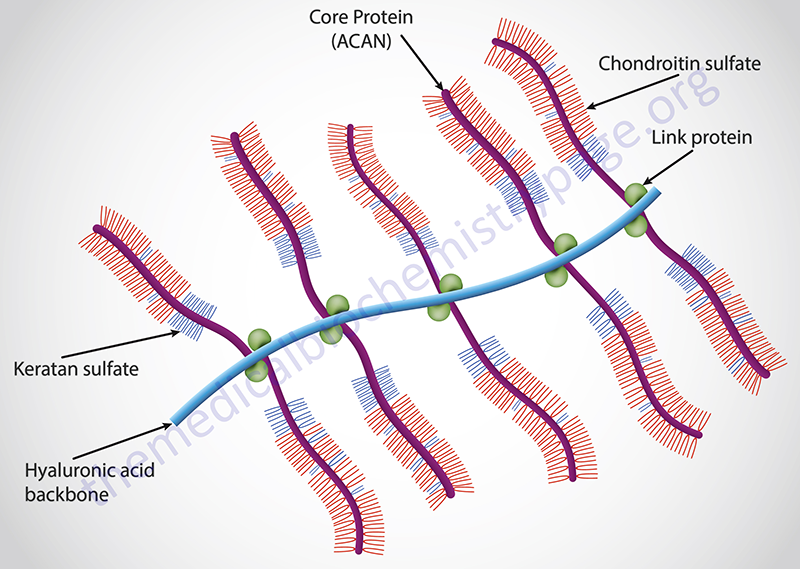

Along with the high viscosity of GAGs comes low compressibility, which makes these molecules ideal for a lubricating fluid in the joints. At the same time, their rigidity provides structural integrity to cells and provides passageways between cells, allowing for cell migration. The specific GAGs of physiological significance are hyaluronic acid, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, heparin, heparan sulfate, and keratan sulfate. Although each of these GAGs has a predominant disaccharide component (see Table below), heterogeneity does exist in the sugars present in the make-up of any given class of GAG.

Hyaluronic acid (also called hyaluronan) is unique among the GAGs in that it does not contain any sulfate and is not found covalently attached to proteins forming a proteoglycan. It is, however, a component of non-covalently formed complexes with proteoglycans in the ECM. Hyaluronic acid polymers are very large (with molecular weights of 100,000–10,000,000) and can displace a large volume of water. Indeed, the hyaluronans are the largest polysaccharides produced by vertebrate cells. The immense size of these molecules makes them excellent lubricators and shock absorbers in the joints.

Table of the Glycosaminoglycan Disaccharides

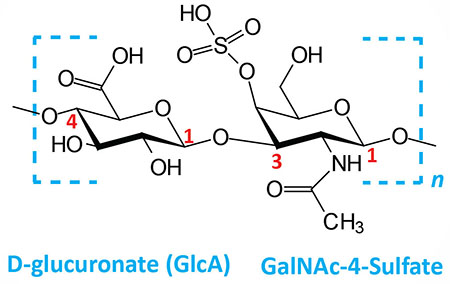

Chondroitin 4- and 6-sulfates: composed of D-glucuronate (GlcA) and GalNAc-4- or 6-sulfate; linkage is β(1,3); this figure contains GalNAc 4-sulfate | |

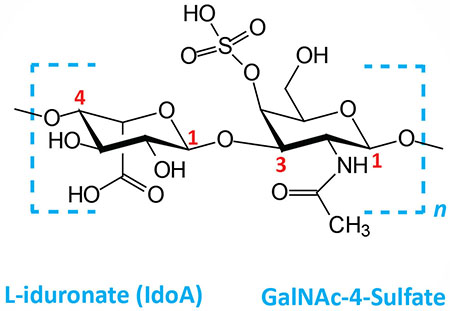

Dermatan sulfates: composed of L-iduronate (IdoA) or D-glucuronate (GlcA) plus GalNAc-4-sulfate; GlcA and IdoA sulfated; linkages is β(1,3) if GlcA, α(1,3) if IdoA | |

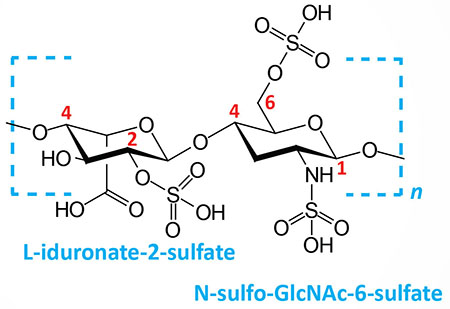

Heparin and heparan sulfates: composed of L-iduronate (IdoA: many with 2-sulfate) or D-glucuronate (GlcA: many with 2-sulfate) and N-sulfo-D-glucosamine-6-sulfate; linkage is α(1,4) if IdoA, β(1,4) if GlcA: heparans have less overall sulfate than heparins | |

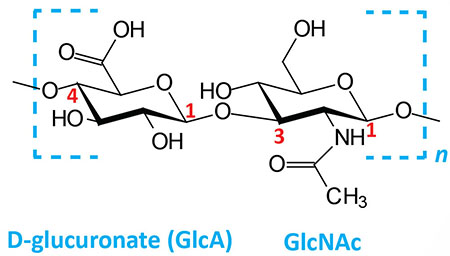

Hyaluronates: composed of D-glucuronate (GlcA) plus GlcNAc; linkage is β(1,3) | |

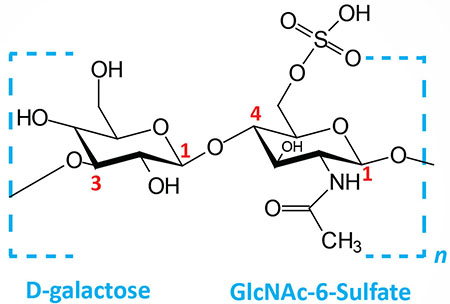

Keratan sulfates: composed of galactose plus GlcNAc-6-sulfate; linkage is β(1,4) |

Carbohydrate Sulfation in Glycosaminoglycans

The sulfate esters and sulfo-amines found in the various sulfated GAGs are generated via the actions of the enzymes of the sulfotransferase family. These enzymes, nearly exclusively, utilize the sulfate donor 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to catalyze sulfate addition to their substrates, where in the case of GAGs these substrates are carbohydrate. Humans express a large family of sulfotransferase genes that includes 37 membrane-bound and 13 cytosolic enzymes.

The membrane-bound sulfotransferase subfamily contains 15 genes that encode enzymes identified as carbohydrate sulfotransferases. The genes encoding these enzymes are designated CHST1–CHST15. There are four membrane-bound galactose-3-O-sulfotransferase genes identified as GAL3ST1–GAL3ST4. Eleven membrane-bound sulfotransferases are involved in the sulfation of heparans and the genes are designated HS2ST1, HS3ST1, HS3ST2, HS3ST3A1, HS3ST3A2, HS2ST4, HS2ST5, HS2ST6, HS6ST1, HS6ST2, and HS6ST3. The first number in the heparan sulfotransferase gene family name refers to the position in the carbohydrate to which the sulfur is transferred. Two membrane-bound sulfotransferases (TPST1 and TPST2) are utilized in the tyrosine sulfation of proteins.

All of the cytosolic sulfotransferase genes have the designation SULT followed by a number-letter combination to designate the family and then a number to designate the specific gene. For example, the SULT2A1 gene belongs to the 2A family and is the first gene in that family. The SULT2A1 gene is involved in the transfer of sulfate to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) forming DHEA-S during the synthesis of the steroid hormones.

The principal enzymes that transfer sulfur to the carbohydrates of chondroitin and dermatan sulfates and proteoglycans composed of these GAGs are chondroitin 4-O-sulfotransferase, chondroitin 4-sulfate-6-O-sulfotransferase, chondroitin 6-O-sulfotransferase, and dermatan 4-O-sulfotransferase:

- Chondroitin 4-O-sulfotransferase is encoded by the CHST11 gene and is primarily involved in the transfer of sulfur to the 4-position of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) in chondroitin.

- Chondroitin 4-sulfate-6-O-sulfotransferase is encoded by the CHST15 gene and is primarily involved in the transfer of sulfur to the 6-position in chondroitin sulfates where there is sulfate at the 4-position.

- Chondroitin 6-O-sulfotransferase is encoded by the CHST3 gene and is primarily involved in the transfer of sulfate to the 6-position of GalNAc in chodroitins and the 6-position of the galactose residues of the tetrasaccharide linker in chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans.

- Dermatan 4-O-sulfotransferase is encoded by the CHST14 gene and is primarily involved in the transfer of sulfur to the 4-position of GalNAc in dermatan sulfates.

- Sulfation of the 6-position of galactose residues in keratans is catalyzed by the CHST1 gene encoded enzyme.

- Sulfation of the 6-position of GlcNAc in keratans is catalyzed by the same enzyme (CHST3) that transfers sulfur to this amino sugar in chondroitin sulfates.

Clinical significance related to the sulfation of GAGs and the GAG chains in proteoglycans can be evidenced from the fact that numerous inherited disorders have been identified that are associated with defects in the genes of sulfate transport across membranes, activated sulfur (PAPS) synthesis, and the numerous sulfotransferases. As described in the Clinical Significances of Tetrasaccharide Linker Synthesis section below, mutations in the CHST3 gene results in a severe developmental disorder.

Mutations in the CHST14 gene are associated with a severe disorder that is a variant form of the family of connective tissue disorders known as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, EDS. The disorder resulting from CHST14 mutations is referred to as EDS musculocontractural type 1, EDSMC1 (also known as Dundar syndrome). This disorder is characterized by distinctive craniofacial dysmorphism that includes a broad, bossed forehead, late-closing fontanel, down-slanting palpebral fissures, posteriorly rotated ears, and downturned angle of mouth. Additional abnormalities associated with EDSMC1 include severe psychomotor developmental delay, club feet, contractures of thumbs and fingers, severe kyphoscoliosis, muscular hypotonia, hyperextensible thin skin with easy bruising, and joint hypermobility.

Table of the Characteristics of GAGs

| GAG | Localization | Comments |

| Hyaluronate | synovial fluid, articular cartilage, skin, vitreous humor, ECM of loose connective tissue | large polymers; molecular weight can reach one million Daltons; high shock absorbing character; average person has 15 gm in body; 30% turned over every day; synthesized in plasma membrane by three hyaluronan synthases: HAS1, HAS2, and HAS3 |

| Chondroitin sulfate | cartilage, bone, heart valves | most abundant GAG; principally associated with protein to form proteoglycans; the sulfation of chondroitin sulfates occurs on the C-2 position of the uronic acid residues and the C-4 and/or C-6 positions of GalNAc residues; the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans form a family of molecules called lecticans and includes aggrecan, versican, brevican, and neurcan; major component of the ECM; loss of chondroitin sulfate from cartilage is a major cause of osteoarthritis |

| Heparan sulfate | basement membranes, components of cell surfaces | contains higher acetylated glucosamine than heparin; found associated with protein forming heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG); major HSPG forms are the syndecans and GPI-linked glypicans; HSPG binds numerous ligands such as fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF); HSPG also binds chylomicron remnants at the surface of hepatocytes; HSPG derived from endothelial cells act as anti-coagulant molecules |

| Heparin | component of intracellular granules of mast cells, lining the arteries of the lungs, liver and skin | more sulfated than heparan sulfates; clinically useful as an injectable anticoagulant although the precise role in vivo is likely defense against invading bacteria and foreign substances |

| Dermatan sulfate | skin, blood vessels, heart valves, tendons, lung | was originally referred to as chrondroitin sulfate B which is a term no longer used; the sulfation of dermatan sulfates occurs on the C-2 position of the uronic acid residues and the C-4 and/or C-6 positions of GalNAc residues; may function in coagulation, wound repair, fibrosis, and infection; excess accumulation in the mitral valve can result in mitral valve prolapse |

| Keratan sulfate | cornea, bone, cartilage aggregated with chondroitin sulfates | usually associated with protein forming proteoglycans; keratan sulfate proteoglycans include lumican, keratocan, fibromodulin, aggrecan, osteoadherin, and prolargin |

Hyaluronans

Virtually all cells in the human body synthesize the hyaluronans. As tissues expand and cells need to migrate, the synthesis of hyaluronans increases. Indeed, hyaluronans have essential roles in development, tissue organization, cell proliferation, and signal transduction processes.

Hyaluronan synthesis is catalyzed by a family of hyaluronan synthases (HAS), each of which contains dual catalytic activities required for the transfer the appropriate sugar residues (N-acetylglucosamine and glucuronic acid), from the corresponding nucleotide-activated sugars (UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-GlcA, respectively), during the formation of the polymers of hyaluronic acid. There are three members of the mammalian HAS gene family, HAS1, HAS2, and HAS3. These genes code for homologous proteins predicted to contain five to six membrane-spanning segments and a central cytoplasmic domain.

Unlike all the other GAGs, hyaluronans are synthesized at the inner surface of the plasma membrane in eukaryotic cells. This mode of synthesis allows for the extrusion of long polymers into the ECM. These hyaluronan polymers are typically on the order of 104 disaccharides in length that exceed 3,000,000 Daltons in mass.

The HAS1 gene is located on chromosome 19q13.41 and is composed of 5 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs resulting in two isoforms of the enzyme of 578 amino acids (isoform 1) and 577 amino acids (isoform 2).

The HAS2 gene is located on chromosome 8q24.13 and is composed of 4 exons that encode a protein of 552 amino acids.

The HAS3 gene is located on chromosome 16q22.1 and is composed of 8 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that together encode two distinct isoforms of the enzyme of 553 amino acids (isoform a) and 281 amino acids (isoform b). The HAS3 encoded protein is thought to function as a regulator of hyaluronan synthesis as opposed to being involved directly in their synthesis.

Hyaluronan function is, in most cases, dependent upon an interaction with proteins present on the surface of the cell and/or secreted into the extracellular matrix (ECM). Hyaluronan-binding proteins were initially discovered in cartilage and this family of proteins is now called the link module family of hyaladherins. ECM linking proteins are necessary for stabilizing proteoglycan aggregates. The various link module proteins contain two motifs, the link module, that specifically interacts with hyaluronan and, as a result, forms the backbone upon which proteoglycan aggregates assemble. This particular proteoglycan is now called aggrecan (see below). The second motif in the link module protein locks the proteoglycan on the hyaluronan chain. Absence of hyaladherins leads to failure in the anchoring of proteoglycans, resulting in defects in cartilage development and delayed bone formation (short limbs and craniofacial anomalies). In addition to aggrecan-type proteoglycans, the versicans, brevicans, and neurocans also consist of a protein core that contains a link domain molecule allowing for, and necessary for hyaluronan interaction.

Hyaluronans are also critical components of complex signal transduction processes. The protein, CD44 (Indian blood group antigen), contains a cytoplasmic domain, a transmembrane domain, and an extracellular domain that contains a single link module that can bind hyaluronans. When CD44 interacts with hyaluronan it alters the activity of CD44 such that the cytoplasmic domain interacts with regulatory and adaptor molecules, such as SRC kinases, GTPases that regulate the RHO family of monomeric G-proteins, a GRB2-associated binding protein (GAB1), and proteins that regulate cytoskeletal assembly/disassembly and cell migration (ankyrin and ezrin). Hyaluronan binding to other transmembrane signaling proteins (such as HMMR: hyaluronan-mediated motility receptor; also known as RHAMM) results in the activation of the kinases, PKC, SRC, ERK1/2, and FAK (focal adhesion kinase). These kinases are involved in the regulation of cell growth and motility. Given that these hyaluronan-activated pathways are relevant to tumor cell survival and invasion, drugs that interfere with the interactions may represent novel therapeutic approaches for treating cancer.

Following synthesis, the hyaluronans can be remodeled and/or catabolized. Hyaluronic acid turnover occurs rapidly in most tissues, taking as little as one day in most epidermal tissues. Despite the rapid turnover, the life-time of hyaluronans can be quite long, in most instances being determined by tissue and location. For example, hyaluronans in cartilage have very long life-spans. Humans express a family of hyaluronan catabolizing enzymes referred to as the hyaluronidase (HYAL) gene family. The HYAL family is composed of six genes with hyaluronidase-like sequence identity. These six genes are clustered into two sets of three contiguous genes located on two different chromosomes. Although these enzymes are referred to as hyaluronidases, several members of the family also have a limited ability to degrade chondroitins and chondroitin sulfates. All of the human hyaluronidases are endo-β-N-acetyl-hexosaminidases. In addition, these enzymes have the ability to cross-link hyaluronic acid to chondroitins and chondroitin sulfates, an activity referred to as transglycosidase. The human HYAL genes are identified as HYAL1, HYAL2, HYAL3, HYAL4, SPAM1/PH-20, and a pseudogene identified as PHYAL1.

The hyaluronidases, HYAL1 and HYAL2, have major roles in the degradation of hyluronic acid in most somatic tissues. HYAL3 has also been shown to exhibit hyaluronidase activity in somatic tissues, but also may serve an important role in sperm function. HYAL4 has not been shown to exhibit hyaluronidase activity but it appears that, despite its amino acid homology to the other hyaluronidases, the enzyme is a chondroitinase. The SPAM1 (also called PH-20 hyaluronidase) encodes the protein identified as SPerm Adhesion Molecule 1. The SPAM1 encoded protein is a GPI-anchored enzyme found on the surface of human sperm and the inner acrosomal membrane. The SPAM1 encoded protein functions as a hyaluronidase that enables sperm to penetrate through the hyaluronic acid-rich cumulus cell layer surrounding the oocyte, it is a receptor involved in hyaluronic acid induced cell signaling, and is also a receptor involved in sperm-zona pellucida adhesion. The PHYAL1 gene is a transcribed pseudogene but the resulting RNA is not translated into protein.

The HYAL1, HYAL2, and HYAL3 genes are clustered on chromosome 3p21.31. The HYAL4 and SPAM1 genes are clustered on chromosome 7q31.32. The HYAL1 gene is composed of 6 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding a total of four distinct protein isoforms. The HYAL2 gene is composed of 6 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs both of which encode the same 473 amino acid protein. The HYAL3 gene is composed of 5 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding a total of four distinct protein isoforms. The HYAL4 gene is composed of 10 exons that encode a 481 amino acid protein. The SPAM1 gene is composed of 9 exons that generate five alternatively spliced mRNAs that together encode two distinct isoforms of the enzyme of 511 amino acids (isoform 1) and 509 amino acids (isoform 2).

Chondroitin Sulfates

The typical chondroitin sulfate disaccharide unit in humans is composed of GalNAc and GlcA, both of which can be highly sulfate modified. Chondroitin sulfate GAGs are polymerized into long chains. The incorporation of sulfur into the chondroitin sulfate sugars is a highly complex process involving multiple sulfotransferases, as is the case for the other types of sulfated GAGs. Many chondroitin sulfate chains are hybrid structures that contain more than one type of chondroitin disaccharide unit. Dermatan sulfates (see next section) are a subtype of chondroitin sulfates that contain one or more iduronic acid-containing disaccharide units. This form of the GAG is sometimes referred to as chondroitin sulfate B. Chondroitin sulfates that contain glucuronic acid in the disaccharide units instead of iduronic acid are referred to as chondroitin sulfates A and C. Chondroitin sulfates, as well as dermatan sulfates, are found attached to a large family of proteoglycan core proteins referred to as lecticans. The lectican family includes aggrecan, brevican, neurocan, and versican. In addition to chondroitin sulfates and dermatan sulfates, the aggrecans and neurocans can also be found to be carrying keratan sulfates dependent upon the tissue source.

As with most all GAGs the repeating disaccharide structure is generated by sequential addition of the corresponding sugar residues to the tetrasaccharide linker (see the Proteoglycans section below) which is itself generated by sequential addition of sugars to the proteoglycan core protein. The addition of GalNAc to the tetrasaccharide linker establishes that the proteoglycan will be either a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG) or a dermatan sulfate proteoglycan (DSPG). The first critical determinant GalNAc residue added to the tetrasaccharide linker in chondroitin and dermatan sulfates is incorporated via the action an enzyme originally identified as chondroitin N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (GalNAcT-I) which is encoded by the CSGALNACT1 gene. The next steps involve the addition of the GlcA of UDP-GlcA followed by the GalNAc of UDP-GalNAc with continuous repeating of GlcA then GalNAc addition forming the GAG polymer attached to the proteoglycan. The enzymes that add the GlcA residues also add the GalNAc residues. There are two human enzyme capable of these reactions and they are referred to as chondroitin sulfate synthase 1 and chondroitin sulfate synthase 3 which are encoded by the CHSY1 and CHYS3 genes, respectively.

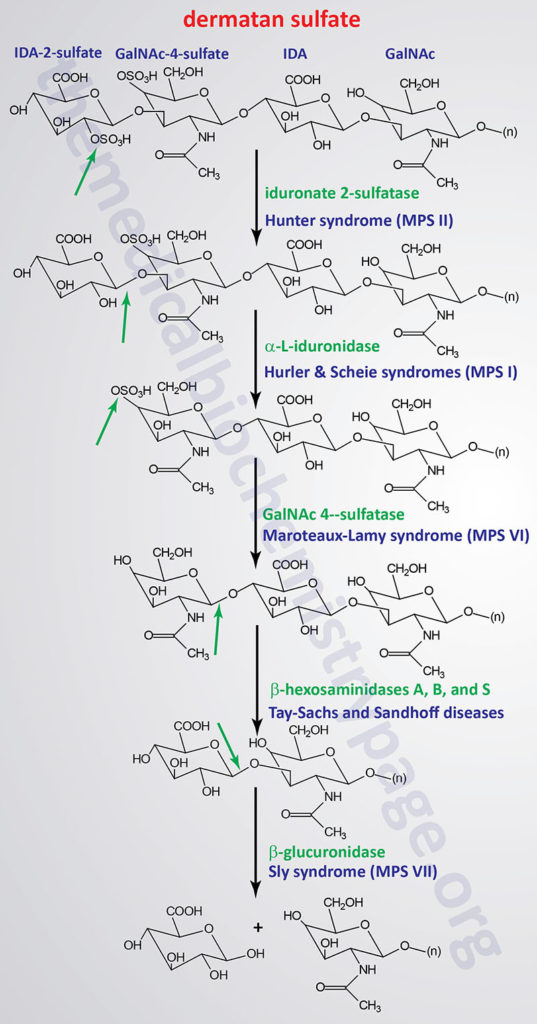

Dermatan Sulfates

Dermatan sulfates in humans are composed of repeating disaccharide units of iduronic acid and GalNAc. The name of this class of GAG is derived from the fact that they represent the predominant GAG in the skin (dermis). Although the presence of GalNAc technically identifies dermatan sulfate as a chondroitin sulfate, the presence of the iduronic acid establishes the dermatan sulfates as a distinct class of GAG. Dermatan sulfates are generated from chondroitin sulfates via the epimerization of the glucuronate (GlcA) residues of chondroitin sulfates to iduronate (IdoA). The epimerization reaction is catalyzed by an enzyme which is often referred to as uronyl C5-epimerase and is encoded by the GLCE (glucuronic acid epimerase) gene. It is likely that epimerization of GlcA to IdoA occurs prior to the addition of sulfate to the adjacent GalNAc residues. What is know regarding dermatan sulfate synthesis is that all of the IdoA residues found in the complex are adjacent to 4-sulfated GalNAc residues.

Dermatan sulfates and dermatan sulfate proteoglycans (DSPG) are responsible for the binding of numerous proteins that are involved in the modulation of a large range of physiological processes. A critical and clinically relevant example being the fact that dermatan sulfates bind to heparin cofactor-II, thrombin, and activated protein C (aPC) and in so doing regulate specific functions of the blood coagulation cascade. Dermatan sulfates also interact with numerous growth factors, such as members of the fibroblast growth factor family (e.g. FGF-2 and FGF-7), thereby playing a role in the regulation of cell proliferation. The proteoglycan, decorin, is a DSPG that is important for the binding of collagen and fibronectin. The interaction between decorin and these ECM proteins serves to function as a regulator of wound repair and skin strength.

Heparin and Heparan Sulfates

Heparin and heparan sulfates are initially composed of GlcNAc and glucuronic acid (GlcA) disaccharide units. Following formation of the disaccharide unit it undergoes extensive modifications. Both disaccharide units are sulfated with heparins being more highly sulfated than heparan sulfates. Heparin is produced solely as serglycin proteoglycan (see below in the Proteoglycans section) by connective-tissue associated mast cells, whereas heparan sulfates are made by virtually all cells of the body. As this family of GAG chains polymerizes, the sugars undergo a series of modification reactions. These modifications are carried out by an epimerase and at least four families of sulfotransferases. Some GlcA residues are sulfated which blocks the epimerization reaction of glucuronate to iduronate (IdoA). As indicated, during synthesis heparin becomes more sulfated than heparan sulfates and also there is a higher degree of GlcA epimerization to IdoA in heparins than in heparan sulfates. In heparin, more than 80% of the GlcNAc residues are first N-deacetylated and then the resultant glucosamine (GlcN) is N-sulfated and more than 70% of the GlcA is epimerized to IdoA.

As is the case for most all GAGs the repeating disaccharide structure is generated by sequential addition of the corresponding sugar residues to the tetrasaccharide linker (see the Proteoglycans section below) which is itself generated by sequential addition of sugars to the proteoglycan core protein. The addition of GlcNAc to the tetrasaccharide linker establishes that the proteoglycan will be either a heparin or heparan sulfate or a keratan sulfate dependent upon the orientation of the glycosidic bond of the GlcNAc residue. If the GlcNAc is added in an α(1→4) linkage the GAG will become a heparin or heparan sulfate.

Upon completion of the tetrasaccharide linker on the protein core of a future heparan sulfate proteoglycan the addition of the determinant GlcNAc is catalyzed by an enzyme originally identified as α-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I (GlcNAcT-I; also known as UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:α-3-D-mannoside β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I) which is encoded by the EXTL2 gene which is ubiquitously expressed in most tissues. Another related enzyme encoded by the EXTL1 gene is expressed almost exclusively in skeletal muscle and the brain. A third member of the EXTL gene family, EXTL3 is also ubiquitously expressed.

The step-wise addition of the GlcA and GlcNAc residues in the heparin and heparan sulfate disaccharide is catalyzed by one of two bifunctional enzymes identified as exostosin glycosyltransferase 1 and exostosin glycosyltransferase 2 which are encoded by the EXT1 and EXT2 genes, respectively. Although both the EXT1 and EXT2 enzymes exhibit glycosyltransferase activity alone they function at much higher levels when associated in EXT1/EXT2 heteromeric complexes. Mutations in the EXT1 and EXT2 genes are associated with the disorders identified as multiple exostoses type I and multiple exostoses type II, respectively. These disorders are characterized by multiple projections of bone capped by cartilage. These deformaties are most often associated with the metaphyses of the long bones, but are also associated with the diaphyses. Deformity of the legs, forearms (resembling Madelung deformity), and hands is frequent in patients harboring either of these mutant genes.

Prior to sulfation, and before any GlcA can be epimerized to IdoA, the GlcNAc residue to which sulfur is added are first N-deacetylated to glucosamine (GlcN) by one of the family of bifunctional enzymes known as N-deacetylase and N-sulfotransferases (NDST). Humans express four NDST genes identified as NDST1–NDST4. Following the reaction catalyzed by the NDST enzymes the epimerization of GlcA to IdoA is catalyzed by an enzyme which is often referred to as uronyl C5-epimerase and is encoded by the GLCE (glucuronic acid epimerase) gene. This is the same enzyme that carries of GlcA epimerization in chondroitin sulfates to generate dermatan sulfates (see section above). The sulfation reactions of heparin and heparan sulfates are catalyzed by one of 11 enzymes of the sulfotransferase family with the predominant reactions being catalyzed by the proteins encoded by the HS2ST, HS3ST, and HS6ST genes. The HS2ST encoded enzyme carries out the 2-O-sulfation of the uronic acids in heparin and heparan sulfates. The HS3ST and HS6ST encoded enzymes carry out the 3-O-sulfation and 6-O-sulfation of glucosamine residues, respectively.

The sulfate modification reactions in heparins and heparan sulfates occur in clusters along the polymerized disaccharide units. This gives rise to segments referred to as N-acetylated (NA), N-sulfated (NS), and mixed domains (NA/NS). The resulting specific arrangement of sulfated residues and uronic acid epimers in heparin and heparan sulfate is responsible for the production of ligand-binding domains such as for fibroblast growth factors (FGF) or antithrombin III.

Heparan sulfates are found associated with three types of core proteins forming various types of proteoglycans. The syndecans, of which there are four different genes, are the most abundant forms of core proteins forming heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG). The syndecans carry heparan sulfate chains primarily near the N-terminus of the core protein. The second class of core proteins that carry heparan sulfates are the glypicans of which there are six genes. The glypicans are so-called because the core protein is tethered to the plasma membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linkage. Both the syndecans and the glypicans can be released from the plasma membrane via proteolysis releasing biologically active HSPG into the circulation. The third class of HSPG core protein consists of perlecan, agrin, and collagen type XVIII.

Keratan Sulfates

The term keratan was originally coined in reference to the fact that this GAG structure was originally identified in the cornea. Keratan sulfates are composed of a highly sulfated poly-N-acetyllactosamine chain [Galβ(1→4)GlcNAc]. The poly-N-acetyllactosamine structure of keratan sulfates is the same as that found attached to many glycoproteins of the N-linkage family as well as the mucins which are members of the O-linkage family of glycoproteins. Humans produce two distinct types of keratan sulfates which are defined by the nature of their linkage to protein in proteoglycans. The major core proteins to which keratan sulfates are attached in forming proteoglycans are member of the small leucine-rich repeat proteins (SLRPs). The SLRP proteins are divided into four subclasses with the class II and class III SLRPs having been found to be decorated with keratan sulfates.

Type I keratan sulfate (KS I) was originally characterized from the cornea. KS I is found primarily linked to a protein core encoded by the KERA gene. The linkage of keratan sulfate to the KERA protein is via an N-asparaginyl glycosidic linkage forming the proteoglycan called keratocan. Although the N-linkage of keratan sulfate to the KERA encoded core protein is the predominant form of KS I, N-linkage of keratan sulfates have also been identified in the cornea attached to lumican and mimecan and within cartilage on the proteins fibromodulin and osteoadherin. Within the cornea KS I proteoglycans maintain the even spacing of type I collagen fibrils which allows for photons of light to pass through the cornea without scattering. Known defects in KS I proteoglycan processing are associated with ocular dysfunction and mutations in the KERA gene cause the disorder known as cornea plana type 2 (CNA2). In patients with CNA2 the cornea lacks the normal convex shape which prevents the correct refraction of light through the lens. Defective sulfation of keratan sulfates causes macular corneal dystrophy and defects in keratan sulfate chain formation result in keratoconus.

Type II keratan sulfate (KS II) represents a skeletal form of keratan sulfate and it is bound to the core protein via a glycosidic linkage to a GlcNAc residue which is attached to the core protein via an O-linkage to Ser or Thr. The structure of the keratan sulfate linkage in KS II is referred to the mucin core-2. Type II KS is found exclusively associated with the proteoglycan core protein aggrecan encoded by the ACAN gene. The keratan sulfate attached to aggrecan consists of a highly sulfated disaccharide where each monomeric sugar residue in the disaccharide is dually sulfated. In addition, KS II has frequent sialylated (N-acetylneuraminic acid, NANA) Gal residues in the disaccharide repeat and the terminal GlcNAc residue is capped with neuraminic acid.

A third form of keratan sulfate linkage to protein is found in the brain and is referred to as KS III. The linkage of keratan sulfate in KS III proteoglycans is via a glycosidic bond to mannose which is O-linked to a Ser in the core protein. Addition of the first GlcNAc residue of the KS III type disaccharide repeat to the mannose linked to the core protein is catalyzed by an enzyme of the mannosyltransferase family identified as protein O-linked mannose β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1 encoded by the POMGNT1 gene.

The generation of the disaccharide repeat of the various types of keratan sulfate proteoglycans is carried out by the step-wise addition of Gal, followed by GlcNAc, via the action of glycosyltransferases. The Gal addition is catalyzed by one of the seven human β1,4-galactosyltransferase enzymes encoded by the B4GALT1–B4GALT7 genes. Addition of the GlcNAc residues is catalyzed by UDP-GlcNAc:βGal β-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 2 encoded by the B3GNT2 gene. During synthesis of the keratan sulfate disaccharide repeat the GlcNAc residues are sulfated at the 6-position prior to the addition of the next Gal residue. The sulfation of GlcNAc in keratan sulfates is catalyzed by the enzyme originally identified as corneal N-acetylglucosaminyl-6-sulfotransferase which is encoded by the carbohydrate sulfotransferase 6 (CHST6) gene. Sulfation also occurs on several of the Gal residues in the keratan sulfate disaccharide and the sulfation reaction is catalyzed by an enzyme originally identified as keratan sulfate galactosyl-6-sulfotransferase which is encoded by the carbohydrate sulfotransferase 1 (CHST1) gene.

Proteoglycans

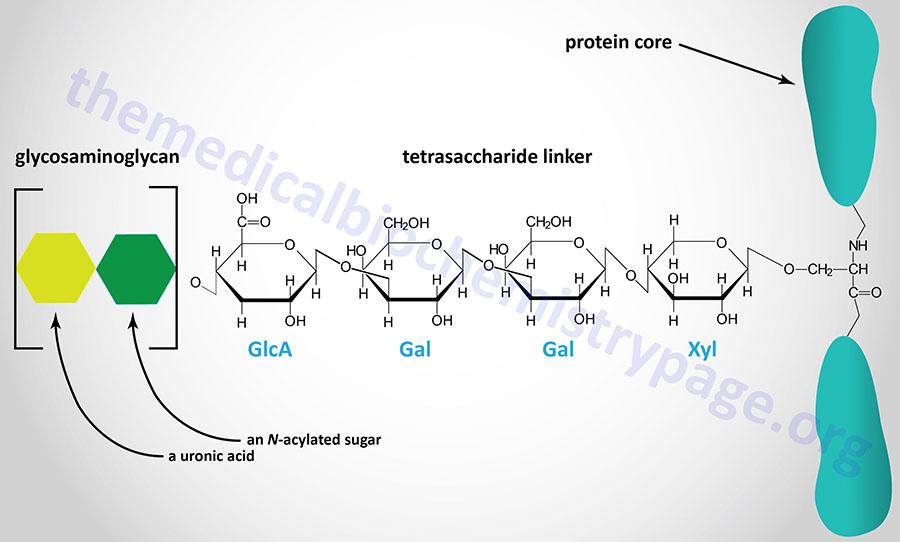

The majority of GAGs in the body are linked to core proteins, forming proteoglycans. The GAGs extend perpendicularly from the core in a brush-like structure. The linkage of GAGs to the protein core, in most but not all proteoglycans, involves a specific tetrasaccharide linker composed of a glucuronic acid (GlcA) residue, two galactose (Gal) residues, and a xylose (Xyl) residue forming a structure such as: GAG(n)–GlcA–Gal–Gal–Xyl–Ser–protein. The tetrasaccharide linker is coupled to the protein core through an O-glycosidic bond to a Ser residue in the protein. The tetrasaccharide linker is most commonly seen in proteoglycans that contain heparins, heparan sulfates, dermatan sulfates, and chondroitin sulfates. Although most common, some GAGs are linked to the protein core of proteoglycans via a trisaccharide linkage that lacks the GlcA residue.

In the case of the keratan sulfates, attachment of the sugar linker to the core protein can occur via O-linkage or via N-linkage. There are two major types of keratan sulfates (KSI and KSII) where KSI containing proteoglycans are formed via N-linkage and KSII containing proteoglycans are formed via O-linkage.

The protein cores of proteoglycans are rich in Ser residues and the sites of GAG attachment are often, but not always, associated with a Ser-Gly/Ala-X-Gly (X refers to the fact that any amino acid can occupy that position) sequence. This potential consensus sequence for GAG attachment is most commonly seen in the protein cores of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG). The presence of multiple Ser residues in proteoglycan core proteins allows multiple sites of polymeric GAG attachment. Following the formation of the tetrasaccharide linker if the next sugar added is N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) the resulting attached GAGs will be either heparins or heparan sulfates. If the next sugar is N-acetlygalactosamine (GalNAc) instead, then the attached GAGs will be either chondroitin sulfates or dermatan sulfates.

Synthesis of the Tetrasaccharide Linker in Proteoglycans

Attachment of the tetrasaccharide linker to a serine residue in the protein core of a proteoglycan is catalyzed in a step-wise manner by a series of specific glycosyltransferases. These glycosyltransferases use the corresponding nucleotide-activated sugars as substrates. The sugars are all activated via UDP attachment.

The enzyme that adds the initiating xylulose residue is called β-xylosyltransferase (XylT; often simply called xylosyltransferase). Humans express two XylT genes identified as XYLT1 and XYLT2. The XYLT1 gene is located on chromosome 16p12.3 and is composed of 14 exons that encode a 959 amino acid precursor protein. The XYLT2 gene is located on chromosome 17q21.33 and is composed of 12 exons generate several alternatively spliced mRNAs only one of which encodes a functional protein of 865 amino acids.

The galactose residues are added by two separate but related enzyme activities identified as β1,4-galactosyltransferase-I (GalT-I) and β1,3-galactosyltransferase-II (GalT-II). The GalT-I enzyme is encoded by the B4GALT7 gene and the GalT-II enzyme is encoded by the B4GALT6 gene. These β1,4-galactosyltransferases represent two members of a family of seven B4GALT enzymes expressed in humans. The B4GALT7 gene is located on chromosome 5q35.3 and is composed of 7 exons that encode a 327 amino acid protein. The B4GALT6 gene is located on chromosome 18q12.1 and is composed of 13 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode four distinct protein isoforms.

The terminal glucuronic acid residue is attached via the action of the enzyme identified as β1,3-glucuronosyltransferase 3 which is encoded by the B3GAT3 gene. The B3GAT3 gene is located on chromosome 11q12.3 and is composed of 6 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs each of which encodes a distinct protein isoform.

In many cases the xylulose residue and the galactose residues are modified by phosphorylation and sulfation, respectively. The xylulose phosphorylation takes place on the C-2 hydroxyl and is catalyzed by a xylosyl kinase encoded by the FAM20B gene. The sulfation of the first galactose residue occurs on the C-6 hydroxyl, whereas sulfation of the second galactose residue can occur on the C-4 or the C-6 hydroxyl of the sugar in chondroitin and dermatan sulfate. In these two GAGs the sulfation reactions are catalyzed by chondroitin 6-O-sulfotransferase 1 which is encoded by the carbohydrate sulfotransferase 3 (CHST3) gene.

Essentially all mammalian cells have the capacity to synthesize proteoglycans and to secrete them into the extracellular matrix (ECM), or insert them into the plasma membrane, or to store them in secretory vesicles. The overall composition of a given type of ECM will ultimately determine the physical characteristics of the tissues it surrounds and also the many biological properties of the cells embedded in it. The proteoglycans found in the ECM interact with other ECM components keeping the level of fluidity high (forming a hydrated gel-like composition) and providing resistance to compressive forces. Different cell types produce different types of membrane-associated proteoglycans. Membrane proteoglycans have either a single membrane-spanning domain (a type I orientation) or they are linked to the membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. In addition, in some cells the proteoglycans are concentrated within secretory vesicles along with the other vesicle components. The role of vesicle proteoglycans is to help sequester and regulate the availability of positively charged vesicle components (e.g. proteases, bioactive trace amines, and certain neurotransmitters) via their interactions with the negatively charged polymeric GAG chains.

There exists a huge variability of proteoglycans in human tissues and cells. This variability is due to several factors including the large number of different proteoglycan core proteins and the ability to add one or two different types of polymeric GAG chains to the protein core. Some proteoglycans contain only one GAG chain (e.g., decorin), whereas others can have several hundred GAG chains (e.g., aggrecan). Proteoglycan variability also results from the stoichiometry of GAG chain substitution. As an example, the proteoglycan, syndecan-1, has five attachment sites for GAGs, but not all of the sites are used equally. Another level of variability results from the fact that different cell types produce proteoglycans, from the same protein core, that exhibit differences in the number of GAG chains, the GAG chain polymeric length, and the arrangement of sulfated residues within the GAG chain.

The various proteoglycans have been divided into several major classes which are defined by their function, tissue distribution, and protein homologies. The major classes include the interstitial proteoglycans, the basement membrane proteoglycans, the secretory granule proteoglycans, and the membrane-bound proteoglycans.

Interstitial Proteoglycans

Interstitial proteoglycans are present in the ECM, and their distribution depends on the nature of the ECM. The interstitial proteoglycans represent a highly diverse class of molecules that differ in size and GAG composition. The majority of interstitial proteoglycans are small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs). The protein cores of SLRPs contain leucine-rich repeats flanked by cysteines in their central domain. To date there are nine members of the SLRP family of proteoglycans. The SLRPs have been shown to contain chondroitin sulfates, dermatan sulfates, and keratan sulfates. Interstitial proteoglycans are critical components in the ECM involved in the stabilization and organization of collagen fibers. The SLRPs are abundant within tendons. Within the cornea, keratan sulfate-containing SLRPs maintain the register of collagen fibers that is required for the transparency of the cornea.

The lectican family (also referred to as the aggrecan family) of interstitial proteoglycans consists of aggrecan, brevican, neurocan, and versican. All four members of this proteoglycan family contain a unique protein core and each core protein contains an amino-terminal domain that can bind hyaluronans, a central domain to which chondroitin sulfates and dermatan sulfates are attached, and a carboxy-terminal domain that contains a C-type lectin domain.

The core protein of aggrecan is encoded by the ACAN gene. The core protein of brevican is encoded by the BCAN gene. The core protein of neurocan is encoded by the NCAN gene. The core protein of versican is encoded by the VCAN gene.

Aggrecan itself is the most well characterized member of aggrecan family and is the major proteoglycan in cartilage. Aggrecan can contain upwards of 100 chondroitin sulfate chains and can also contain keratan sulfate chains dependent upon the tissue of synthesis.

Neurocan is produced in the late embryonic central nervous system (CNS) and can inhibit neurite outgrowth. Brevican is produced in the terminally differentiated CNS.

Versican is produced predominantly by connective tissue cells. The protein core of versican is variable due to alternative splicing of the VCAN mRNA resulting in a family of protein cores in the versicans. Versicans have major roles in neural crest cell and axonal migration.

Basement Membrane Proteoglycans

The basement membrane is not actually a membrane but is a matrix that forms a thin, fibrous organized layer separating tissues from the underlying connective tissue. The basement membrane is found flush against epithelial cells. It is composed primarily of laminin, nidogen, collagens, and proteoglycans. There are at least four different types of proteoglycan found within basement membranes. These proteoglycans are perlecan, agrin, collagen type XVIII, and leprecan.

The GAG chains in perlecan, agrin, and type XVIII collagen are heparan sulfates. Perlecan is also known as heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) of basement membrane. The protein core of perlecan is encoded by the HSPG2 gene. Perlecan is composed of multiple domains that have different functions. Perlecan has been shown to play a role in embryogenesis, tissue morphogenesis, and cartilage development.

The GAG chains in leprecan are chondroitin sulfates, however, some forms of perlecan have also been shown to contain chondroitin sulfates. Leprecan is also known as leucine proline-enriched proteoglycan. The protein core of leprecan is encoded by the LEPRE1 gene.

The protein core of agrin is encoded by the AGRN gene. Agrin is so-called since it was originally characterized at neuromuscular junctions where it is responsible for the aggregation of acetylcholine receptors. Agrin is also functional in renal tubules where its role is in the determination of the filtration properties of the glomerulus.

Secretory Granule Proteoglycans

The major secretory vesicle proteoglycan is serglycin. Serglycin is also known as hematopoietic proteoglycan. The core protein of serglycin is encoded by the SRGN gene. Serglycin is the major proteoglycan found in cytoplasmic secretory granules within endothelial, endocrine, and hematopoietic cells. Serglycin contains a variable number of GAG attachment sites to which either heparin chains or chondroitin sulfate chains are attached. Heparin, a more highly sulfated form of heparan sulfate, is made exclusively on serglycin that is produced in mast cells associated with connective tissue.

Membrane-Bound Proteoglycans

The family of membrane proteoglycans is quite diverse and consists of the syndecans and the glypicans in addition to several other proteoglycan forms. The syndecan family consists of four members, syndecan-1, -2, -3, and -4. Each of the protein cores of the syndecans contains a short hydrophobic domain that spans the membrane, a large extracellular domain that contains the GAG attachment sites, and a smaller intracellular cytoplasmic domain. Syndecan-1 and syndecan-3 have chondroitin sulfate chains attached to the protein core near the membrane-spanning domain and heparan sulfate chains attached to the more distal sites of the core protein. Syndecan-2 and syndecan-4 have only heparan sulfate chains attached to the protein core.

The syndecans are expressed in a tissue-specific manner where they are involved in the regulation and facilitation of cellular interactions with ECM molecules and extracellular growth factors and matrix molecules. The syndecans also are involved in the transmission of signals from the extracellular environment to the intracellular cytoskeletal architecture through their cytoplasmic tails. Because of their membrane-spanning properties, the syndecans can transmit signals from the extracellular environment to the intracellular cytoskeleton via their cytoplasmic tails. The syndecans, like most proteoglycans can, and do, undergo remodeling. In addition, matrix metalloproteases cleave off portions of the extracellular domains of the syndecans resulting in the shedding of what are referred to as ectodomains. The syndecan ectodomains harbor the GAG chains and exhibit potent biological activities on their own.

The glypicans also represent a unique family of membrane-bound proteoglycans. There are six glypican family members in mammals identified as glypican-1 (GPC1) through GPC6. Each of the glypicans is tethered to the plasma membrane via a GPI anchor which is attached at the carboxyl terminus of the protein core. Because of the GPI linkage to the plasma membrane, glypicans do not possess an intracellular cytoplasmic tail like the syndecans. The N-terminal domains of the glypicans fold into globular structures which is another feature that distinguishes this family from the syndecan family. The N-terminal domains of the glypicans also contain multiple Cys residues. Glypican proteoglycans carry only heparan sulfates as the attached GAGs.

Glypican-3 (GPC3) is the most well characterized and studied glypican. This is primarily due to the fact that humans that harbor mutations in the GPC3 gene on the X chromosome suffer from Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome (SGBS).

SGBS is characterized as an overgrowth disorder. This syndrome is characterized by distinctive facial features that includes hypertelorism (widely spaced eyes), macrostomia (unusually large mouth), macroglossia (large tongue), abnormal palate, and a broad upturned nose. This constellation of facial features is commonly referred to as coarse facies or coarse facial features. For this reason it is important that the underlying cause be correctly diagnosed as many inherited disorders in metabolism result in the appearance of coarse facies. In addition to the facial abnormalities, infants with SGBS have chest and abdominal abnormalities, including one or more extra nipples, diastasis recti (abnormal opening in the abdominal muscles), umbilical herniation, or a diaphragmatic hernia (a hole in the diaphragm). Internally there are additional features of SGBS that include heart defects, malformed or abnormally large kidneys, hepatosplenomegaly, and skeletal abnormalities.

Table of the Representative Mammalian Proteoglycan Types

| Proteoglycan | Comments |

| Aggrecan | belongs to the lectican family; a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG); protein core encoded by the ACAN gene; ACAN found on chromosome 15q26.1 composed of 19 exons encoding a 2316 amino acid protein; forms a complex with hyaluronan; major component of articular cartilage |

| Brevican | belongs to the lectican family; a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG); protein core encoded by the BCAN gene; predominantly expressed in the central nervous system; brevican protein devoid of glycosaminoglycan chains is also found within the brain |

| Decorin | is a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) family; protein core encoded by the DCN gene on chromosome 12q21.33 spanning 38 kb composed of 8 exons; binds to type I collagen fibrils; also interacts with fibronectin, thrombospondin, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β); may play a role in epithelial/mesenchymal interactions during organ development |

| Keratocan | a keratan sulfate proteoglycan (KSPG); protein core encoded by the KERA gene on chromosome 12q21.33 spanning 7.7 kb composed of 3 exons; is a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) family, also referred to as the small interstitial proteoglycan gene (SIPG) family; important to the transparency of the cornea |

| Lumican | major keratan sulfate proteoglycan (KSPG); the protein core encoded by the LUM gene found on chromosome 12q21.33 spanning 7.5 kb composed of 3 exons encoding a 338 amino acid protein; is a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) family, also referred to as the small interstitial proteoglycan gene (SIPG) family; present in large quantities in the corneal stroma and in interstitial collagenous matrices of the heart, aorta, skeletal muscle, skin, and intervertebral discs; interacts with collagen fibrils; may regulate collagen fibril organization, corneal transparency, and epithelial cell migration and tissue repair |

| Neurocan | belongs to the lectican family; a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG); a nervous system proteoglycan; protein core encoded by the NCAN gene; NCAN found on chromosome 19p13.11 spanning 41 kb composed of 14 exons encoding a 1321 amino acid protein; is a susceptibility factor for bipolar disorder, absence of the NCAN gene in mice results in a variety of manic-like behaviors which can be normalized by administration of lithium |

| Perlecan | more commonly called heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) of basement membrane; protein core encoded by the HSPG2 gene on chromosome 1p36.12; possesses angiogenic and growth-promoting properties primarily by acting as a coreceptor for fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) |

| Syndecans | a family of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) that act as transmembrane cell surface receptors; consists of four members: syndecan-1, -2, -3, and -4; aberrant syndecan regulation plays a critical role postnatal tissue repair, inflammation and tumor progression; syndecan-1 expression is prevalent in differentiating plasma cells and its expression can serve as a marker for cells that are secreting immunoglobulin; syndecan-2 (also referred to as the original HSPG) prevalent on endothelial cells; strong expression of syndecan-3 found in many regions of the brain; syndecan-4 prevalently expressed in epithelial and fibroblastic cells; protein core of syndecan-1 encoded by the SDC1 gene found on chromosome 2p24.1 encoding a 310 amino acid protein; syndecan-2 protein core encoded by the SDC2 gene on chromosome 8q22.1; protein core of syndecan-3 encoded by the SDC3 gene on chromosome 1p35.2 encoding a 443 amino acid protein; protein core of syndecan-4 encoded by the SDC4 gene on chromosome 20q13.12 |

| Versican | belongs to the lectican family; a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG); protein core encoded by the VCAN gene found on chromosome 5q14.2–q14.3 spanning 90 kb composed of 15 exons; alternative splicing generates three versican species designated V0, V1, and V2 that differ in the length of the attached glycosaminoglycans; one of the main components of the ECM; significant proteoglycan in vitreous body of the eye; participates in cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis; contributes to the development of atherosclerotic vascular diseases, cancer, tendon remodeling, hair follicle cycling, central nervous system injury, and neurite outgrowth; Wagner syndrome is caused by mutation in the VCAN gene, causes vitreoretinal degeneration |

Clinical Significance of Tetrasaccharide Linker Synthesis

Proteoglycans serve significant functions in a wide array of biological and physiological processes. For these reasons it is not surprising that developmental and pathophysiological abnormalities result from defects in the genes encoding enzymes of GAG synthesis and modification as well as genes encoding the enzymes involved in the synthesis of the tetrasaccharide linker to which the GAGs are attached in proteoglycans.

As detailed in the previous section, there are four primary reactions leading to the synthesis of the tetrasaccharide linker. The initial attachment of xylulose to a serine residue in the core protein is catalyzed by either of two xylosyltransferases. The genes encoding the enzymes involved in the tetrasaccharide linker synthesis are XYLT1, XYLT2, B4GALT7, B4GALT6, and B3GAT3 and characterized disorders are known to be associated with mutations in all but the B4GALT6 gene.

A disorder identified as pseudoxanthoma elasticum, PXE (also known as Gronblad-Strandberg syndrome) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that results from mutations in the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family member gene, ABCC6. This disorder is characterized by calcification of the eyes, skin, heart, and several other soft tissues. Mutations in either the XYLT1 gene or the XYLT2 gene are known to modify the severity of the symptoms of PXE.

Mutations in the B4GALT7 gene are associated with the development of a variant form of the family of connective tissue disorders known as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, EDS. The B4GALT7 associated disease is referred to as EDS progeroid type 1, EDSP1. EDSP1 is associated with an aged appearance to the face along with craniofacial dysmorphism characterized by small face, small mouth, short neck, prominent forehead, flattened nasal bridge, protuberant eyes, and small ears. These patients also have an extremely short stature, experience generalized muscular hypotonia, loose ligaments, and dislocations of the elbows, hips, and knees.

Mutations in the B3GAT3 gene are associated with a disorder whose symptoms are similar to those of Larsen syndrome. Larsen syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the filamin B (FLNB) gene and is associated with large-joint dislocations and characteristic craniofacial abnormalities. The disorder caused by B3GAT3 mutations is an autosomal recessive disorder associated with multiple joint dislocations, short stature, and the craniofacial dysmorphisms seen in Larsen syndrome which include hypertelorism, prominent forehead, a depressed nasal bridge, and a flattened midface.

Clinical Significance of Glycosaminoglycan Degradation

Proteoglycans and GAGs perform numerous vital functions within the body, some of which still remain to be elucidated. One well-defined function of the GAG, heparin, is its role in preventing coagulation of the blood. Heparin is abundant in granules of mast cells that line blood vessels. The release of heparin from these granules, in response to injury, and its subsequent entry into the serum leads to an inhibition of blood clotting. Free heparin complexes with, and activates, antithrombin III, which in turn inhibits all the serine proteases of the coagulation cascade. This phenomenon has been clinically exploited in the use of heparin injection for anti-coagulation therapies.

Several genetically inherited diseases, for example the lysosomal storage diseases (lysosomal storage disorders), result from defects in the lysosomal enzymes responsible for the metabolism of complex membrane-associated GAGs. These specific diseases are termed the mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) in reference to the historical term, mucopolysaccharide, used to describe the glycosaminoglycan component of GAG-protein complexes called proteoglycans.

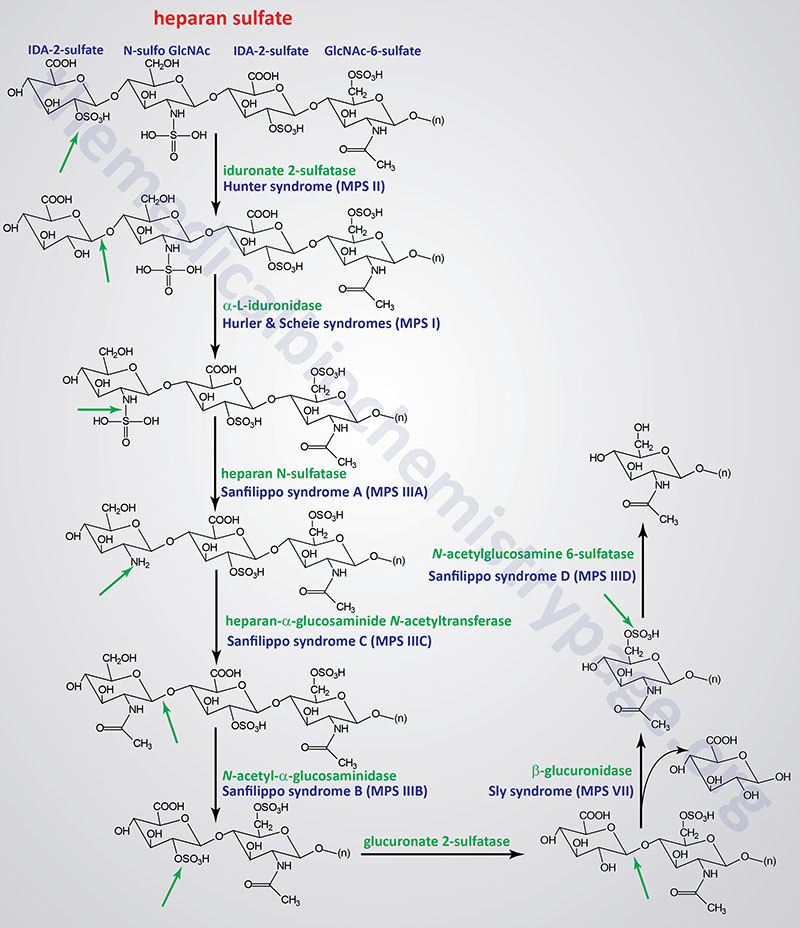

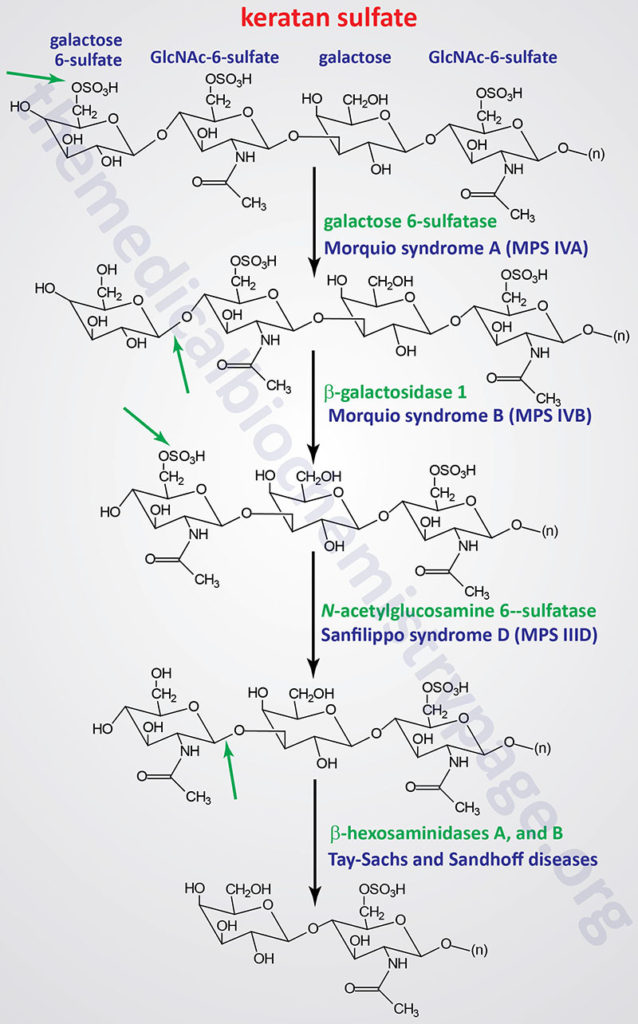

The various MPS lead to an accumulation of GAGs within lysosomes of affected cells. There are at least 14 known types of lysosomal storage diseases that affect GAG catabolism; some of the more commonly encountered examples are outlined in the Table below the following Figures that show the general pathways for the degradation of dermatan sulfates, heparan/heparin sulfates, and keratan sulfates. Included in the Table are links to posts describing several of the MPS diseases. All of these disorders, excepting Hunter syndrome (X-linked recessive), are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

All of the MPS diseases are chronic, progressively debilitating disorders that in many instances lead to severe psychomotor impairment and premature death. In addition, the clinical spectrum of these disorders can vary widely due to the differing effects of different mutations in the same gene.

Pathways of Dermatan Sulfate Degradation

Pathways of Heparan/Heparin Sulfate Degradation

Pathways of Keratan Sulfate Degradation

Table of the Mucopolysaccharidoses

| Disease: MPS Designation | Enzyme Defect / Gene | Affected GAG | Symptoms / Comments |

| Hurler MPS I, MPS IH (MPS1H) | α-L-iduronidase / IDUA | dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate | corneal clouding, dysostosis multiplex, organomegaly, heart disease, dwarfism, intellectual impairment; early mortality |

| Scheie MPS I, MPS IS (MPS1S) | α-L-iduronidase / IDUA | dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate | corneal clouding; aortic valve disease; joint stiffening; normal intelligence and life span |

| Hurler-Scheie MPS I, MPS IHS (MPS1HS) | α-L-iduronidase / IDUA | dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate | intermediate between I H and I S |

| Hunter MPS II (MPS2) | L-iduronate-2-sulfatase / IDS | dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate | mild and severe forms, only X-linked MPS, dysostosis multiplex, organomegaly, facial and physical deformities, no corneal clouding, intellectual impairment, death before 15 except in mild form then survival to 20 – 60 |

| Sanfilippo A MPS III, MPS IIIA (MPS3A) | heparan N-sulfatase (also called N-sulfoglucosamine sulfohydrolase / SGSH | heparan sulfate | profound intellectual deterioration, hyperactivity, skin, brain, lungs, heart and skeletal muscle are affected in all 4 types of MPS-III |

| Sanfilippo B MPS III, MPS IIIB (MPS3B) | α-N-acetyl-D-glucosaminidase / NAGLU | heparan sulfate | phenotype similar to III A |

| Sanfilippo C MPS III, MPS IIIC (MPS3C) | acetylCoA:α-glucosaminide-acetyltransferase (also called heparan-α-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase) / HGSNAT | heparan sulfate | phenotype similar to III A |

| Sanfilippo D MPS III, MPS IIID (MPS3D) | N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase [also called glucosamine (N-acetyl)-6-sulfatase] / GNS | heparan sulfate | phenotype similar to III A |

| Morquio A MPS IV, MPS IVA (MPS4A) | galactose-6-sulfatase (also called [galactosamine (N-acetyl)-6-sulfatase] / GALNS | keratan sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate | corneal clouding, odontoid hypoplasia, aortic valve disease, distinctive skeletal abnormalities |

| Morquio B MPS IV, MPS IVB (MPS4B) | β-galactosidase 1 / GLB1 | keratan sulfate | severity of disease similar to IV A |

| MPS V, a designation no longer used | |||

| Maroteaux-Lamy MPS VI (MPS6) | arylsulfatase B (also called N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase) / ARSB | dermatan sulfate | 3 distinct forms from mild to severe, aortic valve disease, dysostosis multiplex, normal intelligence, corneal clouding, coarse facial features |

| Sly MPS VII (MPS7) | β-glucuronidase / GUSB | heparan sulfate, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin 4-, 6-sulfates | hepatosplenomegaly, dysostosis multiplex, wide spectrum of severity, hydrops fetalis |

| MPS VIII, a designation no longer used | |||

| Mucopolysaccharidosis type IX: MPS IX (MPS9) | hyaluronoglucosaminidase-1 (hyaluronidase)/ HYAL1 | hyaluronic acids | periarticular soft tissues masses on distal extremities and digits; very rare disease; a total of 36 known pathogenic mutations as of 2025 |

| Mucopolysacchaidosis type X: MPS X (MPS10) | arylsulfatase K/ ARSK | dermatan sulfates | metaphyseal striation of the long bones; progressive hip dysplasia; very rare disease with only 10 identified cases as of 2025; a total of 3 known pathogenic mutations as of 2025 |