Last Updated: January 28, 2026

Introduction to Control of Gene Expression

The controls that act on gene expression (i.e., the ability of a gene to produce a biologically active protein) are much more complex in eukaryotes than in prokaryotes. A major difference is the presence in eukaryotes of a nuclear membrane, which prevents the simultaneous transcription and translation that occurs in prokaryotes. Whereas, in prokaryotes, control of transcriptional initiation is the major point of regulation, in eukaryotes the regulation of gene expression is controlled nearly equivalently from many different points.

Gene Control in Prokaryotes

In bacteria, genes are clustered into operons: gene clusters that encode the proteins necessary to perform coordinated function, such as biosynthesis of a given amino acid. RNA that is transcribed from prokaryotic operons is polycistronic a term implying that multiple proteins are encoded in a single RNA molecule.

In bacteria, control of the rate of transcriptional initiation is the predominant site for control of gene expression. As with the majority of prokaryotic genes, initiation is controlled by two DNA sequence elements that are approximately 35 bases and 10 bases, respectively, upstream of the site of transcriptional initiation and as such are identified as the –35 and –10 positions. These 2 sequence elements are termed promoter sequences, because they promote recognition of transcriptional start sites by RNA polymerase. The consensus sequence for the -35 position is TTGACA, and for the –10 position, TATAAT. (The –10 position is also known as the Pribnow-box.) These promoter sequences are recognized and contacted by RNA polymerase.

The activity of RNA polymerase at a given promoter is in turn regulated by interaction with accessory proteins, which affect its ability to recognize start sites. These regulatory proteins can act both positively (activators) and negatively (repressors). The accessibility of promoter regions of prokaryotic DNA is in many cases regulated by the interaction of proteins with sequences termed operators. The operator region is adjacent to the promoter elements in most operons and in most cases the sequences of the operator bind a repressor protein. However, there are several operons in E. coli that contain overlapping sequence elements, one that binds a repressor and one that binds an activator.

As indicated above, prokaryotic genes that encode the proteins necessary to perform coordinated function are clustered into operons. Two major modes of transcriptional regulation function in bacteria (E. coli) to control the expression of operons. Both mechanisms involve repressor proteins. One mode of regulation is exerted upon operons that produce gene products necessary for the utilization of energy; these are catabolite-regulated operons. The other mode regulates operons that produce gene products necessary for the synthesis of small biomolecules such as amino acids. Expression from the latter class of operons is attenuated by sequences within the transcribed RNA.

A classic example of a catabolite-regulated operon is the lac operon, responsible for obtaining energy from β-galactosides such as lactose. A classic example of an attenuated operon is the trp operon, responsible for the biosynthesis of tryptophan.

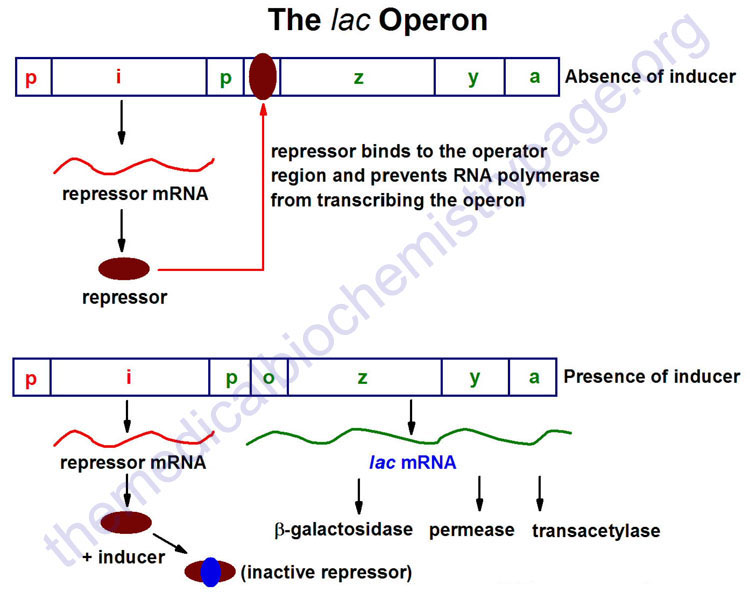

The lac Operon

The lac operon (see diagram below) consists of one regulatory gene (the i gene) and three structural genes (z, y, and a). The i gene codes for the repressor of the lac operon. The z gene codes for β-galactosidase (β-gal), which is primarily responsible for the hydrolysis of the disaccharide, lactose into its monomeric units, galactose and glucose. The y gene codes for permease, which increases permeability of the cell to β-galactosides. The a gene encodes a transacetylase.

During normal growth on a glucose-based medium, the lac repressor is bound to the operator region of the lac operon, preventing transcription. However, in the presence of an inducer of the lac operon, the repressor protein binds the inducer and is rendered incapable of interacting with the operator region of the operon. RNA polymerase is thus, able to bind at the promoter region, and transcription of the operon ensues.

The lac operon is repressed, even in the presence of lactose, if glucose is also present. This repression is maintained until the glucose supply is exhausted. The repression of the lac operon under these conditions is termed catabolite repression and is a result of the low levels of cAMP that result from an adequate glucose supply. The repression of the lac operon is relieved in the presence of glucose if excess cAMP is added. As the level of glucose in the medium falls, the level of cAMP increases. Simultaneously there is an increase in inducer binding to the lac repressor. The net result is an increase in transcription from the operon.

The ability of cAMP to activate expression from the lac operon results from an interaction of cAMP with a protein termed CRP (for cAMP receptor protein). The protein is also called CAP (for catabolite activator protein). The cAMP-CRP complex binds to a region of the lac operon just upstream of the region bound by RNA polymerase and that somewhat overlaps that of the repressor binding site of the operator region. The binding of the cAMP-CRP complex to the lac operon stimulates RNA polymerase activity 20–50 fold.

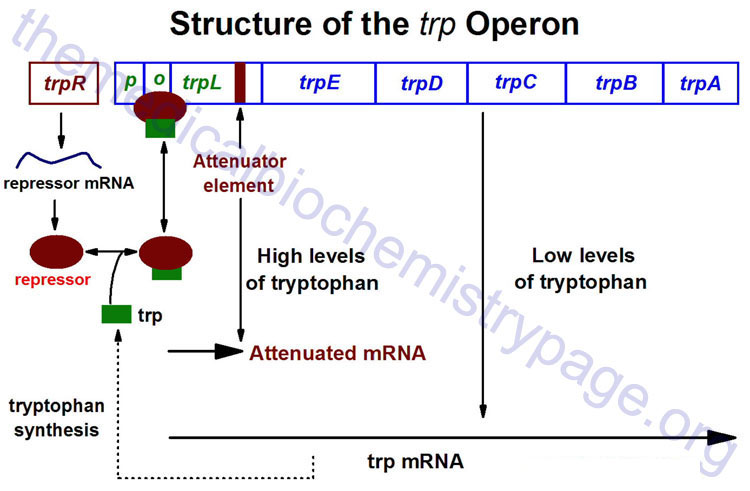

The trp Operon

The trp operon (see diagram below) encodes the genes for the synthesis of tryptophan. This cluster of genes, like the lac operon, is regulated by a repressor that binds to the operator sequences. The activity of the trp repressor for binding the operator region is enhanced when it binds tryptophan; in this capacity, tryptophan is known as a corepressor. Since the activity of the trp repressor is enhanced in the presence of tryptophan, the rate of expression of the trp operon is graded in response to the level of tryptophan in the cell.

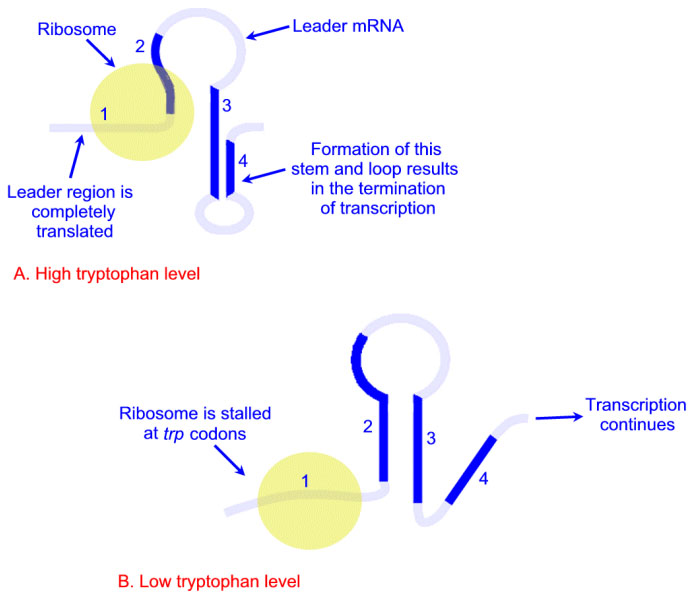

Expression of the trp operon is also regulated by attenuation. The attenuator region, which is composed of sequences found within the transcribed RNA, is involved in controlling transcription from the operon after RNA polymerase has initiated synthesis. The attenuator of sequences of the RNA are found near the 5′ end of the RNA termed the leader region of the RNA. The leader sequences are located prior to the start of the coding region for the first gene of the operon (the trpE gene). The attenuator region contains codons for a small leader polypeptide, that contains tandem tryptophan codons. This region of the RNA is also capable of forming several different stable stem-loop structures.

Depending on the level of tryptophan in the cell and hence the level of charged trp-tRNAs, the position of ribosomes on the leader polypeptide and the rate at which they are translating allows different stem-loops to form. If tryptophan is abundant, the ribosome prevents stem-loop 1–2 from forming and thereby favors stem-loop 3–4. The latter is found near a region rich in uracil and acts as the transcriptional terminator loop as described in the RNA: Transcription and Processing page. Consequently, RNA polymerase is dislodged from the template.

The operons coding for genes necessary for the synthesis of a number of other amino acids are also regulated by this attenuation mechanism. It should be clear, however, that this type of transcriptional regulation is not feasible for eukaryotic cells.

Control of Gene Expression in Eukaryotes

In eukaryotic cells, the ability to express biologically active proteins comes under regulation at several points:

1. Chromatin Structure: The physical structure of the DNA, as it exists compacted into chromatin, can affect the ability of transcriptional regulatory proteins (termed transcription factors) and RNA polymerases to find access to specific genes and to activate transcription from them. The presence modifications of the histones and of CpG methylation most affect accessibility of the chromatin to RNA polymerases and transcription factors.

2. Epigenetic Control: Epigenesis refers to changes in the pattern of gene expression that are not due to changes in the nucleotide composition of the genome. Literally “epi” means “on” thus, epigenetics means “on” the gene as opposed to “by” the gene.

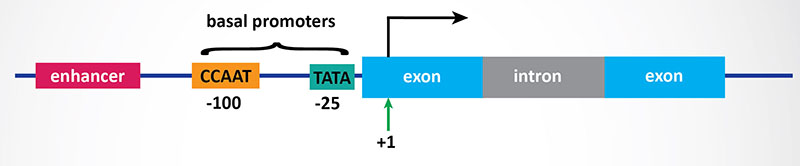

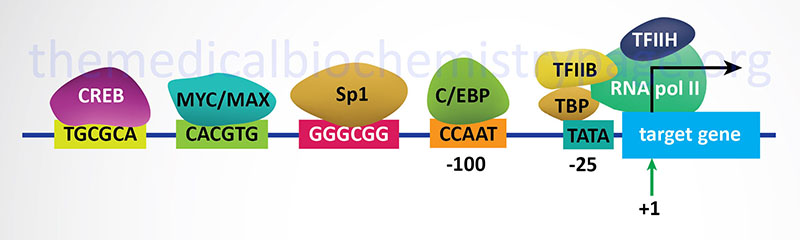

3. Transcriptional Initiation: This is the most important mode for control of eukaryotic gene expression (see below for more details). Specific factors that exert control include the strength of promoter elements within the DNA sequences of a given gene, the presence or absence of enhancer sequences (which enhance the activity of RNA polymerase at a given promoter by binding specific transcription factors), and the interaction between multiple activator proteins and inhibitor proteins.

4. Transcript Processing and Modification: Eukaryotic mRNAs must be capped and polyadenylated, and the introns must be accurately removed (see RNA: Transcription and Processing page). Several genes have been identified that undergo tissue-specific patterns of alternative splicing, which generate biologically different proteins from the same gene.

5. RNA Transport: A fully processed mRNA must leave the nucleus in order to be translated into protein.

6. Transcript Stability: Unlike prokaryotic mRNAs, whose half-lives are all in the range of 1 to 5 minutes, eukaryotic mRNAs can vary greatly in their stability. Certain unstable transcripts have sequences (predominately, but not exclusively, in the 3′-non-translated regions) that are signals for rapid degradation.

7. Translational Initiation: Since many mRNAs have multiple methionine codons, the ability of ribosomes to recognize and initiate synthesis from the correct AUG codon can affect the expression of a gene product. Several examples have emerged demonstrating that some eukaryotic proteins initiate at non-AUG codons. This phenomenon has been known to occur in E. coli for quite some time, but only recently has it been observed in eukaryotic mRNAs.

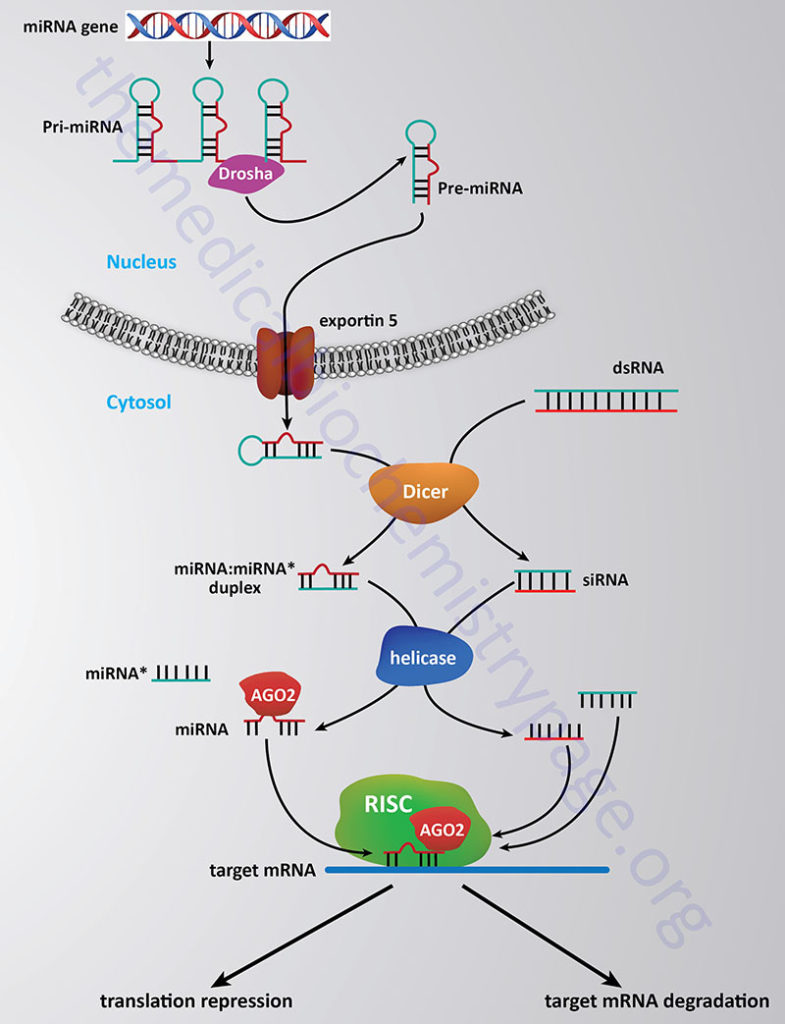

8. Small RNAs and Control of Transcript Levels: Within the past several years a new model of gene regulation has emerged that involves control exerted by small non-coding RNAs. This small RNA-mediated control can be exerted either at the level of the translatability of the mRNA, the stability of the mRNA or via changes in chromatin structure.

9. Post-Translational Modification: Common modifications include glycosylation, acetylation, fatty acylation, methylation, and prenylation.

10. Protein Transport: In order for proteins to be biologically active following translation and processing, they must be transported to their site of action.

11. Control of Protein Stability: Many proteins are rapidly degraded, whereas others are highly stable. Specific amino acid sequences in some proteins have been shown to bring about rapid degradation.

Epigenetic Control of Gene Expression

The term epigenetics was first coined by Conrad Waddington in 1939 to define the unfolding of the genetic program during development. In addition, he coined the term epigenotype to define “the total developmental system consisting of interrelated developmental pathways through which the adult form of an organism is realized“. Clearly this definition encompasses a broad range of concepts dealing with genetics, inheritance, and development. Today the term epigenetics is used to define the mechanism by which changes in the pattern of inherited gene expression occur in the absence of alterations or changes in the nucleotide composition of a given gene.

A literal interpretation is that epigenetics mean “in addition to changes in genome sequence.” The easiest way to understand this concept is to think about the fertilized egg: at the moment of fertilization that single cell is totipotent, i.e. as it divides the daughter cells ultimately differentiate into all the different cells of the organism. The only difference between the various cells of the resultant organism are the consequences of differential gene expression, not due to differences in the sequences of the genes themselves. Evidence indicates that most of the epigenetic modifications are erased during gametogenesis and/or following fertilization.

Several different types of epigenetic gene expression regulatory processes have been identified. As described in the Chromatin Structure and Control of Gene Expression and the Histone Modifications, Chromatin Structure, Transcriptional Regulation sections below, chromatin structure, as a means to control gene expression, can be altered by both DNA modification and histone protein modifications. The role of DNA methylation in these structural changes is likely to be one of the most important epigenetic events controlling, and importantly, maintaining the pattern of gene expression during development. However, the importance of other epigenetic phenomena including the various types of histone modifications cannot be ignored in the overall context of gene regulation via chromatin remodeling. It should be clear that the same events that affect chromatin structure can be defined as epigenetic events leading to alterations in the epigenome.

An additional process that affects chromatin structure, and therefore gene expression, is also considered an epigenetic event and this involves non-coding RNAs such as the small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) which are described below. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA) are also involved in the epigenetic control of gene expression.

The metabolism of components of the diet, and the constituents within cells, represents the primary regulator of the epigenome. All of the histone modifications described below, as well as DNA methylation, are dependent upon metabolic intermediates. Methylation of DNA and histones is regulated by the abundance of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM or AdoMet) which is synthesized from methionine and ATP. The synthesis of SAM is dependent on the availability of substrates and cofactors for 1-carbon metabolism, such as methionine, threonine, serine, glycine, choline, histidine, glucose, and folate.

Histone acetylation requires acetyl-CoA which is produced from acetate, citrate, pyruvate, and lactate by acetyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 1 (ACSS1), ATP citrate synthase (ACLY), the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), respectively.

Acetyl-CoA is also a byproduct of fatty acid β-oxidation, the oxidation of several amino acids, and from ketone bodies. The substrates for the various histone acylations described below all are derived from metabolic reactions involving components that are derived from the diet or from intermediates in the various metabolic pathways taking place in all cells.

The significance of the diet to the epigenome has been clearly defined. For example, the typical Western style diet that is high in fats and carbohydrates has been shown to alter the epigenome within the brain and other tissues resulting in altered feeding behaviors and altered metabolism.

Genomic imprints, that involve CpG methylation, undergo a cycle of establishment, maintenance, and erasure. It is during spermatogenesis and oogenesis when the CpG methylation status is established. In males the CpG methylation imprints are established in prospermatogonia while in females the imprints are established only by the fully grown oocyte stage. The patterns of CpG methylation that arise in the germ cells are maintained following fertilization and throughout early development and in the adult.

During development of the primordial germ cells (PGC), from which sperm and egg will arise, the pattern of CpG methylation is erased. The erasure of the CpG methylation pattern in the PGC ensures the sex-dependent imprint pattern can be established in later stages of spermatogenesis and oogenesis.

The DNA methyltransferases responsible for the establishment of the germline differential methylation patterns are encoded by the DNMT3A and DNMT3B genes. As pointed out below, the protein encoded by the DNMT3L gene (which is highly expressed in germ cells) functions to enhance the activity of the DNMT3a enzyme. Once established, the maintenance of the state of germ cell CpG methylation is the function the DNMT1 methylase. The erasure of the CpG methylation imprints, that occurs in primordial germ cells, is carried out by the TET cytidine demethylases (TET1, TET2, and TET3) as well as by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) as described in the DNA: Chromatin Structure, Replication, DNA Damage Repair page for the general removal of 5mC residues in non-imprinted regions of the DNA.

Whereas, epigenesis plays a vital role in the regulation, control, and maintenance of gene expression leading to the many differentiation states of cells in an organism, recent evidence has identified a linkage between epigenetic processes and disease. Most significant is the link between epigenesis and cancer which has been suggested to be a contributing factor in nearly half of all cancers. A clear demonstration has been made between changes in the methylation status of tumor suppressor genes and the development of many types of cancers.

Epigenetic effects on immune system function have also been identified. In addition, there is evidence suggesting a link between epigenetic processes and intellectual health. Recent work, that focuses on epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS), has identified that a wide array of human diseases are associated with epigenetic biomarkers that are disease specific and that are able to define the susceptibility to certain pathologies.

Chromatin Structure and Control of Gene Expression

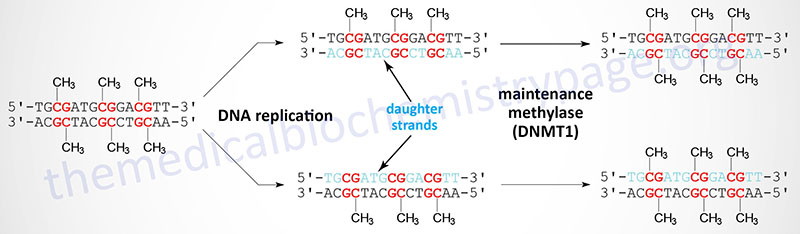

DNA Methylation: Formation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC or m5C)

With respect to DNA methylation, the modification of cytidine residues alters chromatin structure thereby altering transcriptional activity and it is, therefore, considered an epigenetic process. The events of DNA methylation and demethylation are covered in much greater detail in the DNA: Chromatin Structure, Replication, DNA Damage Repair page. When determining which C residues in DNA are targets for methylation it was discovered that greater than 90% of methyl-C is found in the dinucleotide, CpG, where the “p” represents the phosphodiester bond. This is not to say that all CpG dinucleotides contain a methylated C residue. When examining the structure of eukaryotic genes and identifying regions of CpG dinucleotides it is the case that the promoter regions of genes contain 10–20 times as many CpG when compared to the rest of the genome.

In a general sense what is known about DNA methylation and transcriptional status is that when regions of a gene that can be methylated are methylated, the associated gene(s) is(are) transcriptionally silent and when the region is under-methylated the gene(s) is(are) transcriptionally active or can be transcriptionally activated. When cells undergo differentiation it has been observed that genes that become transcriptionally activated exhibit a reduction in methylation status relative to the level prior to activation and that this under-methylation remains even after transcription ceases.

When a C residue in a CpG dinucleotide is methylated the methyl group is attached to the 5-position of the cytidine and is designated 5mC or m5C. The methylation of DNA is catalyzed by several different DNA methyltransferases (abbreviated DNMT). Humans express three DNMT genes identified as DNMT1, DNMT3A (DNMT3 alpha), and DNMT3B (DNMT3 beta).

The DNMT1 gene is located on chromosome 19p13.2 and is composed of 41 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode four distinct protein isoforms. The DNMT1 isoform a is the largest isoform and is a 1632 amino acid protein.

The DNMT3A gene is located on chromosome 2p23.3 and is composed of 34 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding four distinct proteins.

The DNMT3B gene is located on chromosome 20q11.21 and is composed of 24 exons that generate six alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding six distinct protein isoforms.

Another gene, identified as DNMT3L (for DNMT3-like) has some similarities to the DNA methyltransferases but does not have the methyltransferase catalytic amino acids. The activity of the DNMT3L protein stimulates the DNA methyltransferase activity of the DNMT3a enzyme. DNMT3L can also affect transcriptional activity through its association with histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1). Another gene, that was originally designated DNMT2, and thought to be involved in DNA methylation, in fact encodes an enzyme that methylates a specific aspartic acid tRNA. The designation for this gene is now TRDMT1.

When cells divide the DNA contains one strand of parental DNA and one strand of the newly replicated DNA (the daughter strand). If the DNA contains methylated cytidines in CpG dinucleotides the daughter strand must undergo methylation in order to maintain the parental pattern of methylation. This “maintenance” methylation is catalyzed by DNMT1 and thus, this enzyme is called the maintenance methylase. Of the three DNA methyltransferases DNMT1 is the most abundant in all cells. As might be expected from its characterized primary function, DNMT1 has an up to 100-fold higher level of activity towards hemimethylated DNA compared to unmethylated DNA. The activities of DNMT3a and DNMT3b enzymes are relatively equivalent towards unmethylated and hemimethylated DNA. The critical role of DNA methylation in controlling developmental fates was demonstrated in mice by inactivating either DNMT3A or DNMT3B. Loss of either gene resulted in death shortly after birth.

The correlation between DNA methylation and chromatin structure, as it relates to transcriptional activity, is demonstrated by the observation that there are several proteins, that bind to methylated CpG but not to unmethylated CpG, whose functions are integrated into transcriptional regulation. There are currently 15 genes in the human genome that encode proteins that bind to methyl-CpG in DNA. These 15 proteins are divided into 3 subfamilies identified by structural similarities. These sub-families are the methyl binding domain (MBD) proteins, the methyl-CpG-binding zinc finger proteins (also called the Kaiso family), and the SRA domain (SET and RING finger domain Associated) containing proteins. The SET domain is so-called because it was first identified in three Drosophila proteins called Suppressor of variegation variant 3-9 [Su(var)3-9], Enhancer of zeste, and Trithorax. The RING domain is a zinc-finger-like domain which gets its name from the term Really Interesting New Gene.

The first methyl-CpG binding protein to be identified was called methyl-CpG binding protein 1 (MeCP1). The second such protein, and the one most heavily studied, is MeCP2 (methyl-CpG binding protein 2). The MeCP2 protein is encoded by the MECP2 gene which is located on the X chromosome (Xq28) and is composed of 10 exons that generate seven alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode three distinct protein isoforms.

When MeCP2 binds to methylated CpG dinucleotides the DNA takes on a closed chromatin structure and leads to transcriptional repression. The ability of MeCP2 to bind methylated CpG is in turn controlled by its state of phosphorylation. When MeCP2 is phosphorylated it binds with less affinity and the DNA acquires a more open chromatin state.

Rett Syndrome

The importance of MeCP2 in regulating chromatin structure, and consequently transcription, is demonstrated by the fact that deficiencies in this protein, due to mutations in the MECP2 gene, result in Rett syndrome, a disorder with X-linked dominant inheritance. This disorder was first described by Andreas Rett, an Austrian pediatric neurologist.

Rett syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder that occurs almost exclusively in females manifesting as intellectual impairment, seizures, microcephaly, arrested development, and loss of speech. The vast majority of mutations in the MECP2 gene that lead to Rett syndrome are, in fact, new somatic mutations and not inherited. Rett syndrome patients that harbor mutations in the MECP2 gene are heterozygous, containing only one mutant gene.

The reason that mutations in the X-linked MECP2 gene manifest with disease almost exclusively in females is that these mutations are almost always lethal to male fetuses.

Histone Modifications, Chromatin Structure, Transcriptional Regulation

Post-translational modification of histones represents a major epigenetic mechanism for the control of gene expression. These modifications function alone, or in combination, to alter chromatin structural states, thereby effecting changes in the expression of the genes to which the modified histones are associated. Histone modifications occur predominantly on lysine residues and the major modifications are lysine acylations.

The primary control of the various histone lysine acylations involves the availability of intermediates from the various pathways of metabolism. The most well characterized histone lysine acylation is acetylation, designated Kac. The sources of the acetyl-CoA required for lysine acetylation are the metabolic reactions of the oxidation of amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids.

Numerous other lysine acylations, which are characterized as short-chain lysine acylations, have been identified. The most well characterized include β-hydroxybutyrylation (Kbhb), lactylation (Klac), crotonylation (Kcr), succinylation (Ksucc), propionylation (Kpr), butyrylation (Kbu), and malonylation (Kmal). Additional lysine acylations have been identified including 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation (Khib), and glutarylation (Kglu) but these are not covered in the Histone Modifications section.

The enzymes that carry out histone acylations (referred to as “writers”) were originally characterized as histone lysine acetyltransferases (KAT) with five major families of KAT being characterized. These five families are identified as HAT1, GCN5/PCAF (GNAT), MYST, p300/CBP, and SRC. In addition to these five subfamilies there are several other KAT enzymes defined by the sub-classification of “other”. The various KAT families are described in detail in the section describing Histone Acetylation.

In addition to their well characterized KAT activities the GCN5/PCAF, MYST, and p300/CBP family enzymes have been shown to catalyze many of the other protein lysine acylations. In addition to acetylation, the p300 enzyme has been shown to be the most versatile, being able to catalyze histone propionylation, butyrylation, crotonylation, β-hydroxybutyrylation, succinylation, and glutarylation.

Removal of lysine acylations is primarily carried out by enzymes (referred to as “erasers”) that were originally identified as histone deacetylases (HDAC) which includes the the Zn2+-dependent histone deacetylases and the NAD+-dependent sirtuins. Humans express seven genes (SIRT1-SIRT7) encoding sirtuins with all being originally characterized as deacetylases. However, subsequent work has demonstrated that the substrate specificity of the different sirtuins is distinct. SIRT1 and SIRT2 possess depropionylase, debutyrylase, and decrotonylase activities. SIRT5 possesses little deacetylase activity but is active as a desuccinylase, deglutarylase, and demalonylase.

In addition to lysine acylation, histones can be modified by methylation, O-GlcNAcylation, ubiquitylation, and phosphorylation.

Histone Lysine Acetylation (Kac)

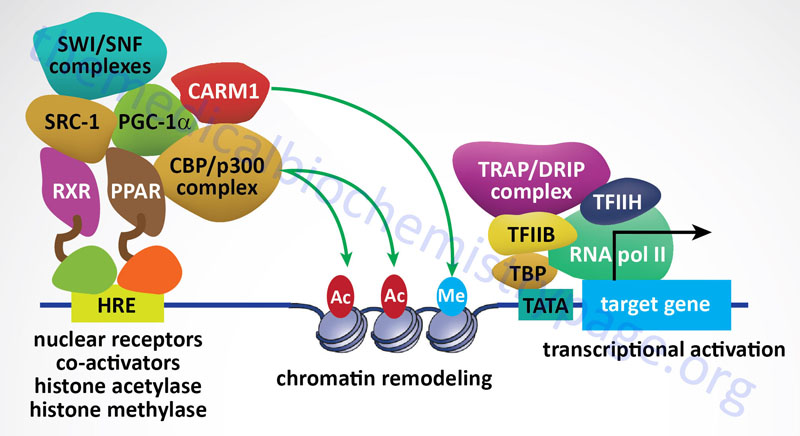

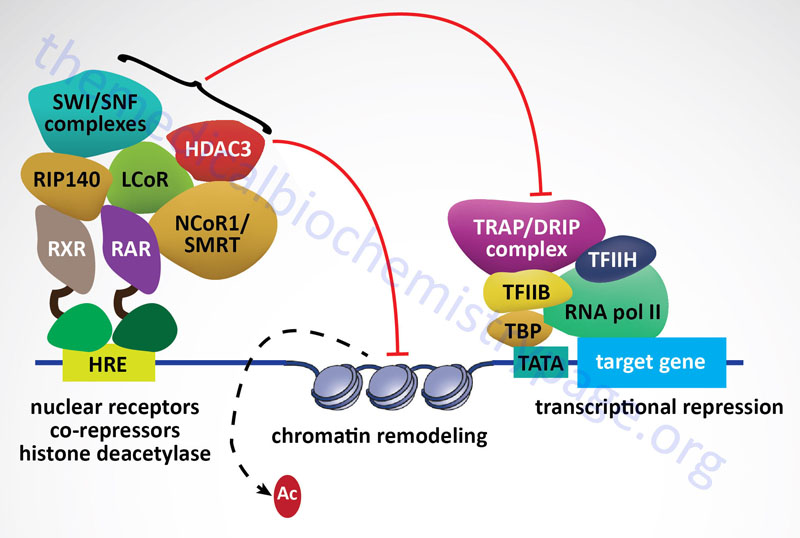

Histone acetylation is known to result in a more open chromatin structure and these modified histones are found in regions of the chromatin that are transcriptionally active. Conversely, under acetylation (deacetylation) of histones is associated with closed chromatin and transcriptional inactivity. A direct correlation between histone acetylation and transcriptional activity was demonstrated when it was discovered that protein complexes, previously known to be transcriptional activators, were found to have histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity. And as expected, transcriptional repressor complexes were found to contain histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity.

Acetyltransferase (“Writers”) Families

Enzymes that acetylate the ε-amino group of lysine residues in proteins in general, and histones in particular, are members of the large family of lysine acetyltransferases (KAT) that is composed of 17 genes in humans. Many of the non-histone proteins that are acetylated are involved in DNA replication, DNA recombination, and DNA repair as well as transcription factors and many other protein types. Global protein analysis has identified over 1,700 human proteins that are modified by acetylation of lysine residues.

The 17 human KAT genes have been classified into five subfamilies based on sequence homology, shared structural features, and substrate acetylation properties. Mammalian histone acetyltransferases (HAT) are either nuclear localized (often referred to as type A HATs) or localized to the cytoplasm (often referred to as type B HATs). All of the nuclear HATs contain a bromodomain allowing them to recognize and interact with acetylated lysines in histone substrates. The cytoplasmic HATs are responsible for acetylating newly synthesized histone proteins prior to their transport into the nucleus.

The original histone acetyltransferase enzyme to be isolated and characterized was identified as HAT1. Within the context of the KAT nomenclature, HAT1 is also known as KAT1. As indicated above, the five human KAT/HAT subfamilies are identified as HAT1, GCN5/PCAF (GNAT), MYST, p300/CBP, and SRC. In addition to these five subfamilies there are several other KAT enzymes defined by the subclassification of “other”.

Each of the KAT enzymes transfers the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to the appropriate lysine residue in the target protein. The fact that these enzymes utilize acetyl-CoA as a substrate, and that their catalytic activities result in altered gene expression, provides a direct link between metabolic processes (those that generate acetyl-CoA) and the regulated transcription of genes.

Linkage between DNA methylation and transcriptional regulation via histone acetylation was demonstrated by the observation that proteins that bind to methyl CpG dinucleotides can recruit HDAC complexes to the DNA. In addition, several proteins are known to interact with acetylated lysines in histones that together lead to a more open chromatin structure. Proteins that bind to acetylated histones contain a domain called a bromodomain. The bromodomain is composed of a bundle of four α-helices and is a domain involved in protein-protein interactions in a number of cellular systems in addition to acetylated histone binding and chromatin structure modification.

HAT1 Subfamily of Acetyltransferases

The HAT1 subfamily is composed of two members, HAT1 and HAT4 [official gene designation is NAA60 for N(alpha)-acetyltransferase 60, NatF catalytic subunit]. The HAT1 subfamily proteins are both cytoplasmic enzymes that acetylate newly synthesized histone proteins. The HAT1 protein acetylates lysine 5 (K5) and K12 in histone H4. It should be noted that some designations include the HAT1 gene in the GCN5/PCAF (GNAT) subfamily.

GCN5/PCAF Subfamily of Acetyltransferases

The GCN5/PCAF subfamily (also known as GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase, GNAT) is so-called because of the initial characterization of the histone acetyltransferase activity of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae GCN5 (general control non-derepressible 5) gene encoded protein. The PCAF gene name is derived from p300/CBP-associated factor. The GCN5/PCAF subfamily consists of the two genes for which the group name is derived, GCN5 (encoded by the KAT2A gene) and PCAF (encoded by the KAT2B gene). The KAT2A and KAT2B encoded proteins acetylate histones H3 and H4.

MYST Subfamily of Acetyltransferases

The MYST subfamily is named for the four initial members of the group; MOZ, YBF2/SAS3, SAS2, and TIP60. The MOZ name is derived from MOnocytic leukemia Zinc finger protein. The SAS proteins were originally identified in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in screens for enhancers of sir1 (yeast sirtuin) epigenetic silencing defects. The identified genes were termed Something About Silencing. The TIP60 name is derived from Tat-Interactive Protein, 60 kDa, where Tat is a gene in the HIV-1 genome. The human MYST subfamily is composed of five proteins, KAT5 (TIP60), KAT6A (MOZ), KAT6B, KAT7, and KAT8. The KAT5 encoded protein acetylates histones H2A and H4. The KAT6A, KAT6B, KAT7, and KAT8 encoded proteins acetylate histones H3 and H4.

p300/CBP Subfamily of Acetyltransferases

The p300/CBP subfamily consists of the two proteins, p300 and CBP, that derived the subfamily name. The p300 protein name is derived from its molecular mass and the protein is encoded by the EP300 (adenovirus E1A binding protein p300) gene. The p300 protein is also defined by the standard KAT nomenclature as KAT3B. The CBP protein name is derived from CREB (cAMP-response element binding protein)-binding protein. The CPB protein is encoded by the CREBBP gene which is also identified by the standard KAT nomenclature as KAT3A. The CREBBP/KAT3A and EP300/KAT3B encoded proteins acetylate all four histones in the nucleosome, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. The p300/CBP acetyltransferases have also been shown to carry out additional lysine modifications that include β-hydroxybutyrylation, crotonylation, succinylation, propionylation, butyrylation, and glutarylation. p300 and CBP are also classified as nuclear receptor co-activators.

SRC Subfamily of Acetyltransferases

The SRC subfamily constitutes the nuclear receptor coregulators that have histone acetyltransferase activity. The SRC name is derived from the original identification of Steroid Receptor Coactivator 1 (SRC-1). SRC-1 is encoded by the NCOA1 gene. The SRC subfamily is composed of three members encoded by the NCOA1, NCOA2 (originally GRIP1 for glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 and also as TIF2 for transcriptional intermediary factor 2), and NCOA3 (originally identified as SRC-3) genes. Each of the SRC subfamily HATs acetylate histones H3 and H4. The NCOA1 encoded protein interacts with other known HATs including KAT3A (CBP), EP300/KAT3B (p300), and KAT2B (PCAF).

Histone Deacetylation (“Erasers”)

Histone deacetylation is necessary to regulate the positive or negative effects on gene expression exerted by histone acetylation. The deacetylation of histones in catalyzed by a large superfamily of enzymes that is composed of the sirtuin (SIRT) genes and the histone deacetylase (HDAC) genes. The HDAC genes are further divided into three subfamilies identified as class I, class II, and class IV. The class II HDAC subfamily is further divided into the class IIA and class IIB subfamilies. The HDAC I subfamily is composed of four genes. The HDAC IIA subfamily is composed of four genes. The HDAC IIB subfamily is composed of two genes. The HDAC IV subfamily is composed of one gene, HDAC11. Little is known about the overall functions of the HDAC11 protein.

The human sirtuin gene subfamily is composed of seven genes identified as SIRT1–SIRT7. The sirtuin genes are often referred to as the class III HDAC subfamily. All of the HDAC enzymes are Zn2+-dependent deacetylases, whereas, the sirtuins are NAD+-dependent enzymes.

HDAC Subfamilies of Deacetylases

All of the class I HDAC enzymes are ubiquitously expressed nuclear localized enzymes. In addition, HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3 are components of multiprotein complexes, whereas, HDAC8 is not. The HDAC1 and HDAC2 proteins form both homodimers and heterodimers with each other. Both HDAC1 and HDAC2 are found in at least three distinct multiprotein corepressor complexes. These corepressor complexes are nucleosome remodeling and deacetylating (NRD; also called NuRD), CoREST [corepressor of REST (RE1 silencing transcription factor)], mSin3, and Nanog- and Oct4-associated deacetylase (NODE). In addition to deacetylation activity supplied by HDAC1 and HDAC2, the CoREST complex recruits the histone demethylase (see next section) KDM1 which demethylates the dimethylated K4 residue in histone H3. HDAC3 is a component of the nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR or NCOR1) and silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT or NCOR2) transcriptional corepressor complexes.

The class IIA HDAC proteins all have tissue specific patterns of expression as well as exhibiting distinct functions. All four of the proteins in the class IIA subfamily are shuttled between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. This shuttling process is regulated by their state of phosphorylation. Because the class IIA HDAC proteins all have an amino acid substitution (Tyr for His) in their catalytic domains, these HDACs have little intrinsic deacetylase activity of their own. The principal function of the class IIA HDACs is binding of acetylated lysine residues in other proteins, thereby recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes to specific target genes. The class IIA HDACs function as deacetylases through their ability to recruit HDAC3-containing corepressor complexes to distinct promoters.

The class IIB HDAC proteins also shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus although they are primarily found only in the cytoplasm. One characteristic feature of this class of enzyme is that they all have duplicated catalytic domains. A major function of cytoplasmic HDAC6 is in the clearance of misfolded proteins through the pathway of autophagy or through the formation of aggresomes.

SIRT Subfamily of Deacetylases

The sirtuins encoded by the SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, and SIRT7 gene function as NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases. The SIRT4 encoded enzyme is a mitochondria localized ADP-ribosyl transferase. The SIRT5 encoded enzyme, in addition to possessing deacetylase activity, functions as a demalonylase and a desuccinylase. The SIRT6 encoded enzyme, in addition to possessing deacetylase activity, functions as a demyristoylase, a depalmitoylase, and an ADP-ribosyl transferase. The deacetylase activity of the sirtuins is not only directed to histones but also to many other acetylated proteins. The human SIRT1 protein is localized to the nucleus and cytosol. The SIRT2 protein is localized to the cytoplasm. SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 are localized to the mitochondria, although SIRT3 has been shown to be in the nucleus and the cytoplasm as well. SIRT6 and SIRT7 are only found in the nucleus with SIRT7 in the nucleolus.

A major function of the sirtuins is in the cell survival pathway. Indeed, in studies on the longevity effects of calorie restriction it was found that a major contributor to the positive effects was the activation of the SIRT1 gene. The sirtuins, specifically SIRT1 and SIRT7, inhibit apoptosis via their ability to deacetylate the tumor suppressor protein, p53. Deacetylation of p53 represses its transcriptional activity which decreases its ability to activate apoptotic gene expression pathways.

Sirtuins are also involved in pathways that inhibit inflammation and regulate overall cellular metabolic rates. SIRT1 and SIRT3 activation leads to deacetylation of the kinase identified as LKB1 (also called STK11 and PJS kinase). Deacetylation of LKB1 results in its activation leading to phosphorylation and activation of the master metabolic regulatory kinase, AMPK. Another major target of sirtuins that results in metabolic regulation is PGC-1α. Activation of PGC-1α by deacetylation results in the activation of gluconeogenic genes and inhibition of glycolytic genes. PGC-1α also activates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. Adipose tissue metabolic processes are also regulated by sirtuin function. SIRT1 in conjunction with the transcriptional corepressor complex NCOR1 represses the transcriptional activation of PPARγ resulting in reduced adipogenesis.

Therapeutic Utility of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

The inhibition of HDAC activity has been shown to upregulate the acetylation level of histones in specific cells as well as in other specific non-histone proteins. HDAC inhibitors modulate the pattern of gene expression, affect DNA damage and repair responses, modulate cell growth, induce apoptosis, and influence autophagy of tumors making them ideal drugs for the treatment of a variety of cancers.

HDAC inhibitors are currently divided into six categories based on their chemical structure with four having received approval from the US FDA for treatment of cancers. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), romidepsin, and belinostat are being used to treat T-cell lymphomas. Panobinostat is being used to treat multiple melanomas. Several HDAC inhibitors are currently being tested for use in the treatment of graft versus host disease (GVHD) and have been shown to reduce proinflammatory cytokine secretion leading to improvement of clinical outcomes post-transplantation.

Histone Butyrylation (Kbu)

Colonic bacteria generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) through fermentation of soluble fiber. These SCFA include acetate, propionate, and butyrate which are absorbed by colonocytes. Metabolically, the gut bacteria-derived SCFA can be used for oxidation or diverted into the ketogenesis pathway. In addition to hepatocytes, gut epithelial cells are the only other cell to express the HMGCS2 gene allowing them to contribute to ketone synthesis. However, gut-derived SCFA also exert other important cell signaling effects.

Gut butyrate is transported into intestinal epithelial cells via several transporters including SLC16A1 (commonly identified as monocarboxylate transporter 1, MCT1), SLC16A3 (commonly identified as monocarboxylate transporter 4, MCT4), SLC5A8 (also known as sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporter 1,SMCT1), and ABCG2 (also known as breast cancer resistance protein, BCRP).

Although the beneficial effects of these SCFA can be attributed to all three, the most extensively studied effects are those exerted by butyrate. Butyrate promotes colonocyte cell differentiation, suppresses colonic inflammation, and of clinical significance it induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in colon cancer cells. These beneficial effects of butyrate (and also shown for propionate), within the colon are mediated, in part, by its ability to inhibit the activity of histone deacetylases (HDAC).

Like all protein lysine acylations, butyryl-CoA represents the substrate for lysine butyrylation (Kbu) of histone proteins as well as other non-histone proteins. Butyryl-CoA is generated via mitochondrial β-oxidation of fatty acids and also via mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis.

Most of the gut-derived butyrate is metabolized by intestinal epithelial cells. Nonetheless, gut microbiota-derived butyrate is utilized by intestinal epithelial cells for the butyrylation of epithelial cell histones. Histone lysine butyrylation is carried out via the actions of several acetyltransferases including p300, CBP, GCN5, PCAF, and MOF. Removal of lysine butyrylation is most likely the result of the sirtuins, SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT3.

Major sites of histone butyrylation in intestinal epithelial cells are histone H3 lysine 9 (designated H3K9bu), lysine 18 (designated H3K18bu), and lysine 27 (designated H3K27bu). Experiments in mice have shown that the formation of H3K9bu and H3K27bu (these lysine residues are conserved in human and murine H3 proteins) is dependent on butyrate formation from gut microbiota. Histone H4 lysines that are shown to undergo butyrylation include lysine 12 (designated H4K12bu).

Histone lysine butyrylation of histone H3 lysine 18 (designated H3K18pr) and of histone H4 lysine 12 (designated H4K12pr) are the same sites of propionylation. These sites of butyrylation and propionylation are found to be differentially distributed in normal versus cancerous colonic epithelial cells. These observations indicate that butyrate and propionate produced by microbiota metabolism increases epithelial homeostatic gene expression pathways that can lead to impairment of carcinogenesis as a result of direct histone modification.

Butyrate that enters the portal circulation is taken up by hepatocytes and metabolized such that the circulating levels are generally quite low. Within intestinal epithelial cells and hepatocytes butyrate is converted to butyryl-CoA through the actions of acyl-CoA synthetase 2 (encoded by the ACSS2 gene). However, there is conflicting data regarding the validity of ACSS2 as functioning butyryl-CoA generating enzyme.

Mitochondrial butyryl-CoA is converted to butyryl-carnitine by carnitine O-acetyltransferase (encoded by the CRAT gene). The transport of butyryl-carnitine from the mitochondria to the cytosol is carried out carnitine acylcarnitine translocase, CACT. The CACT transporter is a member of the SLC family of transporters and as such is encoded by the SLC25A20 gene. The carnitine acylcarnitine translocase is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it facilitates acylcarnitine transport across the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes in exchange for free carnitine.

Accumulation of butyryl-CoA is characteristic of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (SCADD). Indeed, measurement for elevated plasma butyryl-carnitine is a diagnostic feature in patients with SCADD.

Histone β-Hydroxybutyrylation (Khbh)

Like butyrate, the ketone, β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), has also been shown to inhibit the activity of HDAC. The effects of β-hydroxybutyrate-mediated HDAC inhibition are enhanced expression of genes that reduce the level of oxidative stress.

In addition to altering the patterns of gene expression through modification of HDAC activity, β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) can alter gene expression patterns by serving as a direct modifier of lysine residues in histones and many other non-histone proteins resulting in lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation. The effects histone β-hydroxybutyrylation, on gene expression, represent a novel form of epigenetic control. The level of histone β-hydroxybutyrylation is similar to the level of the more well studied epigenetic modification, histone acetylation.

In order for BHB to be utilized for lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation it must first be activated by CoA attachment. The most likely candidate enzyme for this reaction is acyl-CoA synthetase short chain 2, encoded by the ACSS2 gene. The β-hydroxybutyrylation reaction is catalyzed by the acyltransferase identified as histone acetyltransferase p300, encoded by the EP300 gene. This enzyme is also responsible for acetylation, propionylation, and crotonylation of numerous proteins. Although EP300 does indeed carry out lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation there are likely to be additional acetyltransferases involved in this important post-translational modification. Removal of BHB from sites of lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation is most likely catalyzed by histone deacetylases with HDAC1 and HDAC2 being the most likely enzymes.

An important consequence of histone β-hydroxybutyrylation is altered gene expression profiles in the liver. Experiments have shown that increases in β-hydroxybutyrylation in hepatocytes occur in response to prolonged fasting. These effects of BHB are found to be associated with starvation-responsive genes that effectively couples ketogenic metabolism with the control of gene expression.

Histone lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation has been shown to be associated with changes in expression of numerous genes such as the gene for the transcriptional co-activator, PGC-1β (gene symbol: PPARGC1B) which is itself involved in the regulation of expression of numerous genes involved in energy homeostasis, the insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) gene whose encoded protein is involved in insulin signaling, and the carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1) gene whose encoded protein regulates the ability of the mitochondria to oxidize long-chain fatty acids.

Within the liver, in addition to histones, more than 250 proteins have been identified as targets for lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation. These proteins are involved in fatty acid and amino acid metabolic pathways, one-carbon metabolism, and pathways of cellular detoxification. Genes that are expressed in the liver in response to starvation have been identified as associated with β-hydroxybutyrylation of lysine 9 in histone H3 (H3K9bhb).

Histone Lactylation (Kla)

Glycolysis serves as the metabolic pathway for the generation of lactate and its production is a balance between glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism. Conditions such as hypoxia and bacterial infection induce the production of lactate via glycolysis. The role of intracellular lactate in histone modification was demonstrated by inhibition of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) and inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) which results in reduced levels of histone lactylation (also referred to as lactoylation). Histones, and many other proteins, undergo lysine lactylation by both enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms.

Recent studies have demonstrated that production of lactoyl-CoA from lactate is catalyzed by an enzyme of the acyl-CoA synthetase family, specifically the enzyme encoded by the ACSS2 (acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 2) gene.

Another recently identified lactoyl-CoA synthetase activity is a complex of the GTP-specific form of succinyl-CoA synthetase (GTPSCS) of the TCA cycle and the histone acetyltransferase, p300. This complex lactylates histone H3 at lysine 18 (H3K18la). H3K18la resulting in the regulation of expression of the GDF15 gene.

A member of the lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) family that has been shown to function as a lactyltransferase is the KAT2A encoded enzyme which was originally identified as GCN5. The activities of ACSS2 and KAT2A function in concert to lactylate histone H3 resulting in altered expression of several genes whose encoded proteins allow tumor cells to escape immune system detection.

In addition to KAT2A, enzymatic histone lysine lactylation has been shown to be carried out by the histone acetyltransferase (HAT), p300/CBP. Histone lysine lactylation has been found on histones H3, H4, and H2B. In a model of bacterial challenge in macrophages in culture it has been shown that over 1200 genes can be identified as possessing lactylated histone H3.

A major site of histone H3 lactylation is lysine 18 (H3K19la), a modification that serves to activate transcription. In addition to lactylation of K18 in histone H3, additional lysines in H3 have been found to be sites for lactylation including K9, K14, and K56. These three sites of H3 lactylation are associated with the increased levels of lactate production that are typical in cancer as well as in inflammatory states.

Lactylation of histone H4 is also associated with certain disease states such as cancer. In the case of histone H4, the lactylation of lysine 12 (H4K12la) plays a major role in disease. The H4K12la modification has been shown to activate the expression of genes whose encoded enzymes are involved in glycolysis as well as in other pathways of metabolism. In addition to K12, additional sites of lactylation in histone H4 have been identified including K51 and K81.

The clinical significance of protein lactylation is demonstrated by the fact that one of the hallmarks of the metabolic changes associated with cancer is the increased metabolism of glucose to lactate. Indeed, in many cancers the expression of the LDHA gene is significantly upregulated. The increased levels of LDH contribute to increased lactate production and consequently an increase in histone, and other protein, lactylation.

In addition to histones, numerous other proteins, such as metabolic enzymes, undergo lysine lactylation resulting in altered catalytic activity.

Histone Crotonylation (Kcr)

The post-translational modification of proteins by the attachment of crotonate (but-2-enoic acid) to lysine residues was first identified in 2011 in the context of histone proteins, and subsequently shown to be a modification in numerous other proteins. This modification is referred to as lysine crotonylation. Crotonate is a short-chain unsaturated fatty acid that is found in plants and is also an intermediate, as crotonyl-CoA, in the metabolism of the amino acids tryptophan and lysine, and the metabolism of certain fatty acids.

The conversion of crotonate to crotonyl-CoA most likely occurs as the result of the action of the nuclear localized form of acyl-CoA synthetase 1 (ACSS1) or ACSS3. The cellular concentration of crotonyl-CoA is 3-fold lower in comparison to the concentration of acetyl-CoA. This means that the histone lysine crotonylation reaction is much less abundant than histone acetylation as a modification.

Lysine crotonylation is catalyzed by crotonyltransferases and its removal is catalyzed by decrotonylases. Histone

acetyltransferases (HAT) have been shown to have histone crotonyltransferase (HCT) activity. As described, there are three major families of HAT enzymes p300/CBP, GNAT, and MYST. The first HAT complex identified as being able to carry out histone crotonylation was p300/CBP. In in vitro experiments p300/CBP-mediated histone crotonylation was shown to enhance transcription to a greater level than acetylation by p300/CBP. Subsequent to the identification of p300/CBP as being able to carry out histone crotonylation, members of the MYST family, specifically the acetyltransferase encoded by the KAT8 gene (also known as MOF which was isolated in Drosophila melanogaster and called Males-absent On the First), were also found to catalyze histone crotonylation.

Histone deacetylases (HDAC) have been identified as possessing histone decrotonylase (HDCR) activity. The first HDAC shown to possess HDCR activity was histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3). Subsequently the sirtuins, SIRT1 and SIRT2, were shown to be able to decrotonylate histones.

Recognition of crotonylated proteins is associated with proteins possessing a double PHD finger (DPF) domain as well as members of the YEATS domain family, both of which are known to interact with acetylated proteins. Members of the YEATS domain protein family have a much higher affinity for crotonylated proteins compared with acetylated proteins. The PHD (plant homeodomain) finger domain is a type of zinc finger (Cys4-His-Cys3) originally found in plant homeodomain containing proteins. The YEATS domain was originally identified as a domain found in five yeast proteins (Yaf9, ENL, AF9, Taf14, and Sas5), hence the derivation of the acronym.

Histone Propionylation (Kpr)

Propionyl-CoA is the substrate for protein lysine propionylation. Propionyl-CoA is generated predominantly within the mitochondria from the oxidation of the amino acids methionine, threonine, isoleucine, and valine, and from the oxidation of fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms. Propionyl-CoA is also generated in the peroxisomes from the oxidation of methyl branched-chain fatty acids such as phytanic acid. Metabolic studies have demonstrated that isoleucine oxidation is the major contributor to the propionyl-CoA utilized as the substrate for nuclear histone propionylation with valine oxidation being the second major source of nuclear propionyl-CoA.

Mitochondrial propionyl-CoA is transferred out of the mitochondria by carnitine acylcarnitine translocase, CACT. The CACT transporter is a member of the SLC family of transporters and as such is encoded by the SLC25A20 gene. The carnitine acylcarnitine translocase is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it facilitates acylcarnitine transport across the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes in exchange for free carnitine. The propionyl-CoA is then transported into the nucleus where it serves as the substrate for histone propionylation.

The processes of histone propionylation and de-propionylation are catalyzed by many of the same enzymes that carry out histone acetylation and deacetylation. Histone propionylation has been demonstrated to occur through the enzymatic actions of enzymes of three of the HAT families, GCN5/PCAF, p300,/CBP, and MYST. Specifically GCN5 (KAT2A), PCAF, p300, CBP, and MOF have been shown to propionylate histones. Histone de-propionylation has been shown to be carried out by the sirtuin family member enzymes, SIRT1 and SIRT2.

Histone lysine propionylation has been identified in histone H3 lysine 18 (designated H3K18pr) and in histone H4 lysine 12 (designated H4K12pr). These same lysines are also subject to butyrylation. These sites of butyrylation and propionylation are found to be differentially distributed in normal versus cancerous colonic epithelial cells indicating that butyrate and propionate produced by microbiota metabolism increases epithelial homeostatic gene expression pathways that can lead to impairment of carcinogenesis as a result of direct histone modification.

Histone Succinylation (Ksucc)

Like all protein lysine acylations, succinyl-CoA represents the substrate for lysine succinylation (Ksucc) of histone proteins as well as other non-histone proteins. Succinyl-CoA can be derived from several sources and pathways with the most prevalent being from the TCA cycle. Mitochondrial succinate is transported out of the mitochondria via the action of SLC family transporter encoded by the SLC25A10 gene.

Succinyl-CoA is also produced from propionyl-CoA which is an intermediate in the catabolism of the amino acids isoleucine, valine, methionine, and threonine, and from the catabolism of fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms, and from the peroxisomal oxidation of dicarboxylic acids. The predominant site of protein succinylation is within the mitochondria followed by the nucleus. However, there is ample evidence of cytoplasmic protein succinylation.

The transport of 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) from the mitochondria to the cytosol is carried out by SCL25A11. Succinyl-carnitine is transported out of the mitochondria by carnitine acylcarnitine translocase, CACT. The CACT transporter is a member of the SLC family of transporters and as such is encoded by the SLC25A20 gene. The carnitine acylcarnitine translocase is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it facilitates acylcarnitine transport across the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes in exchange for free carnitine. Succinate is transported out of the mitochondria via the action of SLC25A10.

Cytosol 2-oxoglutarate is transported into the nucleus where nuclear-localized 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (OGDHc; also known as α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase) oxidizes it to succinyl-CoA. Cytoplasmic succinyl-carnitine and succinate are converted to succinyl-CoA, most likely via the action of one or more members of the acyl-CoA synthetase family of enzymes. The succinyl-CoA is then transported into the nucleus.

Peroxisomal succinyl-CoA is hydrolyzed to succinate via the action of peroxisomal succinyl-CoA thioesterase which is encoded by the ACOT4 gene. The succinate is then transported to the cytosol where is can be converted to succinyl-CoA again and transported into the nucleus.

Succinyl-CoA is a sufficiently energetic compound that non-enzymatic succinylation can occur. Despite this, enzymatic succinylation has been described. The “writer” for enzymatic lysine succinylation has been shown to be the GCN5/PCAF family member GCN5 (KAT2A). The nuclear OGDHc interacts with GCN5 allowing the succinyl-CoA that is generated to be directly accessible by the acetyltransferase.

De-succinylation of mitochondrial and nuclear succinylated proteins has been shown to be catalyzed by two members of the sirtuin family, SIRT5 and SIRT7. SIRT5 activity is the major mitochondrial de-succinylase but also functions within the nucleus. SIRT7 functions as a histone desuccinylase in the processes of DNA damage repair. SIRT7 is recruited to sites of double-strand break (DSB) by polyADP-ribose polymerase 1 (PARP1) where it de-succinylates lysine 122 of histone H3 (H3K122). The de-succinylation of H3 promotes chromatin condensation and efficient DSB repair.

Histone Malonylation (Kmal)

Malonyl-CoA is the product of acetyl-CoA carboxylation via the action of the acetyl-CoA carboxylases, ACC1 and ACC2. Malonyl-CoA a major substrate for fatty acid synthase (FAS) in the de novo synthesis of fatty acids. ACC2 is closely associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane localized enzyme, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1). The generation of malonyl-CoA by ACC2 allows for rapid inhibition of the activity of CPT1, thereby limiting the mitochondrial oxidation of newly synthesized fatty acids. Given its function in activation of fatty acid synthesis and inhibition of fatty acid oxidation, malonyl-CoA is critical regulator of overall fatty acid homeostasis. Within the mitochondria, malonyl-CoA is generated by the enzyme encoded by the ACFS3 (acyl-CoA synthetase family member 3) gene in the process of mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis.

Lysine malonylation occurs predominantly non-enzymatically. Numerous proteins have been identified as being malonylated including many metabolic enzymes. Several enzymes of glycolysis, including glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (encoded by the GPI gene), phosphoglycerate kinase (encoded by the PGK1 gene), aldolase A (encoded by the ALDOA gene), and enolase (encoded by the ENO1 gene) are modified by lysine malonylation. The TCA cycle enzyme, malate dehydrogenase (encoded by the MDH2 gene) has also been shown to undergo lysine malonylation.

Removal of lysine malonylation has been shown to occur through the action of the sirtuin, SIRT5. Although lysine malonylation of many proteins, including all four of the nucleosomal histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4), the functional significance of these modifications has not yet been fully characterized.

Histone Methylation (“Writers”)

Another histone modification known to affect chromatin structure is methylation. Methylation of histones, as well as numerous other non-histone proteins, occurs on lysine and arginine residues. The enzymes that carry out these methylation reactions are often referred to as “writers”.

Lysine methylation of histones can result in three distinct states, monomethylation, dimethylation, or trimethylation. However, with histone lysine methylation there is not a direct correlation between the modification and a specific effect on transcription. Histone lysine (K) methylation at certain positions is associated with regions of transcriptionally silenced chromatin, whereas methylation at other positions is associated with transcriptionally active regions of DNA.

Histone arginine (R) methylation has been shown to be associated with the promotion of an open chromatin structure and thereby, resulting in transcriptional activation.

Methylation of lysine (K) residues in histone H3 (specifically K9 and K27) and histone H4 (K20) is associated with regions of transcriptionally silenced chromatin. These specific methylation sites are identified as H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20. The monomethylation of H3K9 (H3K9me) and the trimethylation of H3K27 (H3K27me3) are hallmark features of transcriptionally repressed chromatin. The polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which is critical to the processes of X chromosome inactivation, is a large complex whose catalytic core is composed of six subunits, two of which are enzymes (the EZH1 and EZH2 gene encoded proteins) that trimethylate H3K27. The EZH1 and EZH2 encoded proteins are also identified as KMT6B and KMT6A, respectively.

Conversely, methylation at H3K4, H3K36, and H3K79 is associated with transcriptionally active domains in chromatin. However, these associations are not concrete given that H3K36 methylation has been shown to be associated with repression of intragenic transcription initiation.

All lysine methyltransferase enzymes belong to the large superfamily of enzymes identified as the methyltransferase family. Humans express six large families of methyltransferases identified as the (1) homocysteine methyltransferase family, the (2) lysine methyltransferase family, the (3) radical S-adenosylmethionine domain containing family, the (4) seven-beta-strand (7BS) methyltransferase motif containing family, the (5) SET domain containing family, and the (6) SPOUT methyltransferase domain containing family.

The SPOUT nomenclature is derived from the identification of sequence homology between the SpoU and the TrmD methyltransferases, where Trm refers to tRNA methyltransferase. SpoU was originally identified as TrmH. Several of the 7BS methyltransferase motif containing family enzymes, as well as the SPOUT methyltransferase domain containing family of enzymes, methylate nucleotides in tRNA, mRNA, and DNA.

The homocysteine methyltransferase family contains 3 genes. The lysine methyltransferase family contains 34 genes. The radical S-adenosylmethionine domain containing family contains 9 genes. The seven-beta-strand (7BS) methyltransferase motif containing family is composed of four subfamilies, two of which are themselves composed of subfamilies. The SET domain containing family is composed of 35 genes and one subfamily [PR/SET domain (PRDM) family] that itself contains 19 genes. Many of the SET domain containing family enzymes are lysine methyltransferase (KMT) enzymes. The SPOUT methyltransferase domain containing family contains 8 genes.

Lysine methylation was originally thought to be a permanent covalent mark, providing long-term signaling, including the histone-dependent mechanism for transcriptional memory. However, it has become clear that lysine methylation, similar to other covalent modifications, can be transient and dynamically regulated by an opposing demethylation activity. Methylation of lysine residues affects gene expression not only at the level of chromatin modification, but also by modifying the activity of numerous transcription factors.

Within the context of protein methylation, the lysine methyltransferases are organized into the lysine methyltransferase family (34 genes), the SET domain containing family (19 of the 35 genes in the family), and the 7BS protein lysine methyltransferase subfamily (16 genes). The 7BS protein lysine methyltransferase enzymes are a subfamily of the 7BS methyltransferase family which contains both lysine and arginine methyltransferase subfamilies. The 7BS methyltransferase family is itself a subfamily of the 7BS methyltransferase motif containing family of genes.

Many of the lysine methyltransferase encoding genes use the KMT [lysine (K) MethylTransferase] nomenclature. Several of the histone lysine methyltransferases are also identified as HMTases (for Histone MethylTransferases). Not all of the human protein lysine methyltransferase encoding genes encode enzymes that methylate histones.

The enzymes that carry out histone lysine methylation are all members of the SET-domain-containing family of methyltransferases except for one enzyme, DOT1 (disruptor of telomeric silencing 1) like histone lysine methyltransferase (encoded by the DOT1L gene).

The SET domain is so-called as it was originally identified in three Drosophila melanogaster proteins identified as Suppressor of variegation variant 3-9 [Su(var)3-9], Enhancer of zeste, and Trithorax. The SET domain is composed of approximately 130 amino acids.

There are additional histone methyltransferases that belong to a different protein family identified as the PR and SET domain containing transcription factor family, identified as the PRDM family. The PR domain of all of the PRDM family members contains a zinc finger domain. The PR/SET domain family contains 19 members with PRDM2 (also identified as KMT8), PRDM8, PRDM9 (see Figure below), and possibly PRDM14 possessing histone methyltransferase activity.

Several different lysine residues in histones are targets for methylation. Within histone H1, lysine 26 (K26) has been shown to be methylated. Within histone H3, the lysines K4, K9, K27, K36, and K79 are all known to be methylated. Within histone H4, lysines K20 and K59 have been shown to be methylated.

The single non-SET-domain containing histone lysine methyltransferase is encoded by the DOT1L gene catalyzes the methylation of K79 in histone H3 (H3K79).

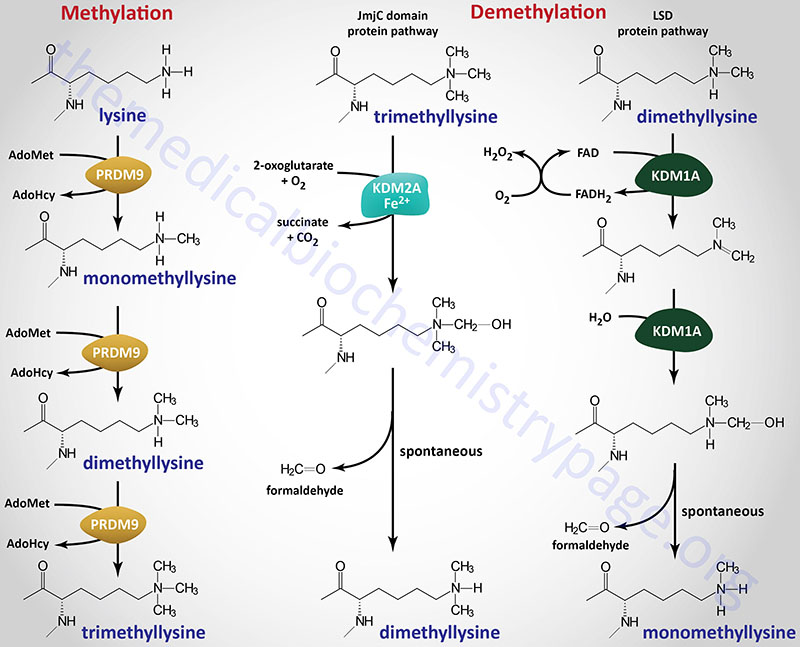

Methylation of lysine residues in histones, and other target proteins, by the KMT family enzymes involves the use of S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet or SAM) as the methyl donor. The products of the reaction are a methylated lysine and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHcy). The different histone lysine methyltransferases incorporate one (monomethyl), two (dimethyl), or three (trimethyl) methyl groups onto their target lysine as exemplified by the PRDM9 enzyme shown in the Figure.

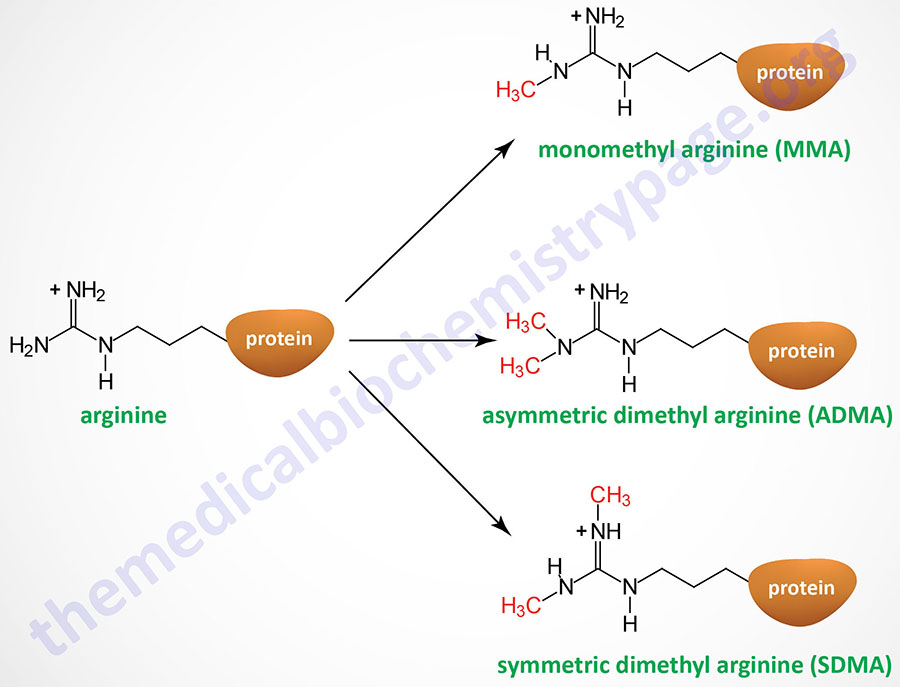

Arginine methylation of histone, and other target proteins, is catalyzed by family of enzymes designated the protein arginine methyltransferase (PRMT) family. There are 11 genes in the human genome that encode arginine methyltransferase enzymes, eight of which are identified with the PRMT nomenclature (PRMT1-PRMT3 and PRMT5-PRMT9). The other three enzymes in this family are CARM1 (coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase 1), METTL23 (methyltransferase 23, arginine), and NDUFAF7 (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex assembly factor 7).

Arginine residues in histones H2A, H3, and H4 are known to be methylated. Arginine methylation in histones, and other proteins, can be of three distinct types: monomethyl (MMA), symmetric dimethyl (SDMA), and asymmetric dimethyl (ADMA).

The PRMT1 encoded enzyme was the first to be shown to methylate arginine residues if histone proteins. The PRMT1 enzyme incorporates an asymmetric dimethylation on Arg 3 (R3) of histone H4. The consequences of H4R3 methylation are enhanced transcriptional activity. Indeed, the PRMT1 protein is considered a transcriptional coactivator and it is recruited to promoters by a number of different transcription factors. The coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1; also known as PRMT4) incorporates asymmetric dimethylation on R17 and R26 of histone H3. Like PRMT1, CARM1 is considered a transcriptional coactivator. Conversely, the PRMT5 encoded enzyme is a potent transcriptional repressor. The PRMT5-mediated incorporation of a methyl group into R3 of histone H4 imparts a strong transcriptional repressive action.

Methylation of arginine residues in histones, and other target proteins, involves the use of AdoMet as for the histone lysine methyltransferases. The products of the PRMT catalyzed reactions are a methylated arginine and S-adenosylhomocysteine.

The methylation of histones provides a site for the binding of other proteins which then leads to alteration of chromatin structure. Proteins that bind to methylated lysines present in histones (as well as other proteins) contain a domain called chromodomain. The chromodomain consists of a conserved stretch of 40–50 amino acids and is found in many proteins involved in chromatin remodeling complexes. In addition, chromodomain proteins are found in the RNA-induced transcriptional silencing (RITS) complex which involves small interfering RNA (siRNA) and microRNA (miRNA)-mediated downregulation of transcription (see below). Another important chromodomain-containing protein is heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1). The presence of methylated H3K9 provides a binding site for HP1 which leads to transcriptional repression due to the formation of heterochromatin (highly compact densely staining chromatin).

Histone Demethylation (“Erasers”)

Histone demethylation is carried out by a distinct families of enzymes that are often referred to “erasers”. The largest family (with numerous subfamilies) of histone demethylases directly reverse histone methylation. An additional family of enzymes indirectly reverses the histone methylation state. All of the histone demethylase enzymes are composed of multiple functional domains. These domains are required for recognition of the correct methylated amino acid in the target histone protein, binding of required cofactors, and carrying out the catalytic reaction.

The largest subfamily of histone demethylase enzymes all contain a domain called the Jumonji C (JmjC) domain. Conserved protein domains giving rise to the JmjC nomenclature were originally identified in the protein encoded by the mouse Jumonji gene. Mutations in the Jumonji gene resulted in an abnormal morphology of the neural plates such that they looked like a cross and “jumonji” means cruciform in Japanese. The jumonji protein was shown to have a domain at the N-terminus and another at the C-terminus that were similar to domains in numerous other proteins, e.g. several transcription factors. These domains were thus called the JmjN and JmjC domains. The JmjC domain in histone demethylases is responsible for cofactor binding in these enzymes.

There are at least 33 human genes that encode JmjC-domain-containing proteins and these 33 proteins can be subdivided into 8 subfamilies. The subfamily of JmjC domain-containing histone demethylases is identified as the JmjC-domain-containing histone demethylase (JHDM) family and also known as the JMJD family. All of the JHDM/JMJD subfamily enzymes, that catalyze demethylation of lysine residues in histones, belong to a larger family of enzymes (at least 80 human family members) that are 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases (2-OGDD). The JHDM enzymes can reverse all three known states of histone lysine methylation. For example JHDM1A reverses H3K36 mono- and dimethylation and H3K4 trimethylation, whereas, JHDM2A reverses H3K9 mono- and dimethylation.

Another subfamily, composed of the originally identified histone demethylases, was originally called the lysine specific demethylase (LSD) family since the founding member, a nuclear amine oxidase homolog, was called lysine specific demethylase 1 (LSD1). This subfamily of histone demethylase enzymes directly reverses histone H3K4 or H3K9 methylations by an oxidative reaction that requires the vitamin-derived cofactor, FAD. The LSD family enzymes have only been shown to demethylate mono- and dimethylated histones and not the trimethylated forms.

Another enzyme shown to demethylate arginine residues in histones is a JmjC domain-containing enzyme identified as JMJD6. The primary function of the JMJD6 encoded enzyme is to hydroxylate lysine residues in target proteins. However, the enzyme has been shown to demethylate H3R2 and H4R3 residues.

As a result of the large number of histone lysine demethylase enzymes and the different subfamily designations a more refined nomenclature system was adopted. All enzymes that demethylate methylated lysines in histone proteins, as well, as other proteins, are now identified as KDM family enzymes where KDM stands for lysine (K) DeMethylase. Humans express 25 genes in the KDM family. There are currently eight KDM subfamilies of enzymes divided based upon factors such as substrate preference, presence of certain domains, and cofactor requirements.

The KDM subfamilies are KDM1 (KDM1A and KDM1B), KDM2 (KDM2A and KDM2B), KDM3 (KDM3A-KDM3C), KDM4 (KDM4A-KDM4E), KDM5 (KDM5A-KDM5D), KDM6 (KDM6A, 6B, and 6C), KDM7A (single gene), and KDM8 (single gene). There is a KDM4F gene but it is a pseudogene.

Within the context of this new nomenclature human JHDM1A is more correctly identified as KDM2A (KDM2 subfamily) and human JHDM2A is KDM3A (KDM3 subfamily). The human LSD homologs, LSD1 and LSD2 are encoded by the KDM1A and KDM1B genes, respectively.

Two proteins of the PHF (PHD finger domain containing) family, PHF2 and PHF8, are also lysine demethylases. Both of the encoded proteins are JmjC-domain-containing histone demethylases. The PHF2 gene encoded protein is also identified as KDM7C and the PHF8 encoded protein is also identified as KDM7B.

There are at least two additional genes whose encoded enzymes are not strictly demethylases but have been shown to demethylate lysine residues in histones. These genes are LOXL2, and RIOX1.

The LOXL2 encoded enzyme is lysyl oxidase like 2. LOXL2 carries out oxidative deamination of lysine residues on target proteins with trimethylated histone H3 (H3K4me3) being one specific target.

RIOX1 was originally identified as NO66 for nucleolar protein 66. The RIOX1 encoded enzyme contains a JmjC domain and is also a 2-oxoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenase (2-OGDD) family enzyme. The primary function of the RIOX1 enzyme is the catalysis of ribosomal protein histidine hydroxylation.

An additional family of enzymes, that is not strictly a histone demethylase family, converts methyl-arginine residues to citrulline as opposed to direct reversal of the methylation reaction. This family of enzymes was originally referred to as the peptidylarginine deiminase (PADI) family. PADI4 was the first enzyme in the family to be identified to catalyze demethylation of methylated arginine in histones. The catalytic activity of PADI4 functions as a histone deiminase that converts methyl-arginine to citrulline as opposed to directly reversing arginine methylation. Although PADI4 has a clear role in antagonizing methylarginine modifications, it cannot strictly be considered a histone demethylase as it produces citrulline instead of an unmodified arginine.

Regulation of Histone Demethylase Activity via Phosphorylation

Numerous histone demethylases have their activity regulated by their state of phosphorylation. The kinases that have been identified as participating in the phosphorylation of histone demethylases include AKT/PKB, PKA, mTORC1, PKC (specifically the PKCα isoform), GSK3β, ERK2, and AMPK.

The consequences of histone demethylase phosphorylation are quite varied and do not simply reflect changes in demethylase activity. Demethylase phosphorylation can lead to changes in the subcellular localization of the protein. In some cases, such as with KDM4C phosphorylation, the protein is targeted for ubiquitylation and consequent degradation. Phosphorylation of KDM1A alters its demethylase activity such that instead of histone demethylation it demethylates other proteins with which it forms complexes, such as RelA. RelA is also known a transcription factor p65 and it is involved in homodimerization of the transcription factor, NFκB. Phosphorylation of KDM1A also alters the proteins with which it interacts allowing for demethylase-independent effects. Phosphorylation of certain histone demethylases can induce the dissociation of histone deacetylases in a complex which allows for the activation of gene expression independent of the demethylase activity.